Published online Nov 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16726

Revised: June 19, 2014

Accepted: July 29, 2014

Published online: November 28, 2014

Processing time: 221 Days and 9.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the safety/efficacy of Boceprevir-based triple therapy in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-G1 menopausal women who were historic relapsers, partial-responders and null-responders.

METHODS: In this single-assignment, unblinded study, we treated fifty-six menopausal women with HCV-G1, 46% F3-F4, and previous PEG-α/RBV failure (7% null, 41% non-responder, and 52% relapser) with 4 wk lead-in with PEG-IFNα2b/RBV followed by PEG-IFNα2b/RBV+Boceprevir for 32 wk, with an additional 12 wk of PEG-IFN-α-2b/RBV if patients were HCV-RNA-positive by week 8. In previous null-responders, 44 wk of triple therapy was used. The primary objective of retreatment was to verify whether a sustained virological response (SVR) (HCV RNA undetectable at 24 wk of follow-up) rate of at least 20% could be obtained. The secondary objective was the evaluation of the percent of patients with negative HCV RNA at week 4 (RVR), 8 (RVR BOC), 12 (EVR), or at the end-of-treatment (ETR) that reached SVR. To assess the relationship between SVR and clinical and biochemical parameters, multiple logistic regression analysis was used.

RESULTS: After lead-in, only two patients had RVR; HCV-RNA was unchanged in all but 62% who had ≤ 1 log10 decrease. After Boceprevir, HCV RNA became undetectable at week 8 in 32/56 (57.1%) and at week 12 in 41/56 (73.2%). Of these, 53.8% and 52.0%, respectively, achieved SVR. Overall, SVR was obtained in 25/56 (44.6%). SVR was achieved in 55% previous relapsers vs. 41% non-responders (P = 0.250), in 44% F0-F2 vs 54% F3-F4 (P = 0.488), and in 11/19 (57.9%) of patients with cirrhosis. At univariate analysis for baseline predictors of SVR, only previous response to antiviral therapy (OR = 2.662, 95%CI: 0.957-6.881, P = 0.043), was related with SVR. When considering “on treatment” factors, 1 log10 HCV RNA decline at week 4 (3.733, 95%CI: 1.676-12.658, P = 0.034) and achievement of RVR BOC (7.347, 95%CI: 2.156-25.035, P = 0.001) were significantly related with the SVR, although RVR BOC only (6.794, 95%CI: 1.596-21.644, P = 0.010) maintained significance at multivariate logistic regression analysis. Anemia and neutropenia were managed with Erythropoietin and Filgrastim supplementation, respectively. Only six patients discontinued therapy.

CONCLUSION: Boceprevir obtained high SVR response independent of previous response, RVR or baseline fibrosis or cirrhosis. RVR BOC was the only independent predictor of SVR.

Core tip: After menopause liver disease in hepatitis C virus-positive women becomes rapidly progressive, severe fibrosis develops, and response to antiviral therapy becomes very low. Re-treatment with standard dual therapy in previous failures of Peginterferon-α + Ribavirin (PEG-IFNα/RBV) treatments does not achieve more than 5%-10% sustained virological response (SVR). The addition of Boceprevir to PEG-IFNα/RBV in menopausal women with HCV-1 genotype infection, who had previously failed dual antiviral therapy, determined a striking improvement of SVR. More than 45% of women re-treated with triple therapy achieved SVR, with few side effects and good tolerability. Response after 4 wk of Boceprevir was the only independent factor predicting SVR.

- Citation: Bernabucci V, Ciancio A, Petta S, Karampatou A, Turco L, Strona S, Critelli R, Todesca P, Cerami C, Sagnelli C, Rizzetto M, Cammà C, Villa E. Boceprevir is highly effective in treatment-experienced hepatitis C virus-positive genotype-1 menopausal women. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(44): 16726-16733

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i44/16726.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16726

Menopausal women with chronic hepatitis C are a group of patients with remarkably distinctive characteristics when compared with women of reproductive age or with males of similar age[1,2]. Acceleration of fibrosis in the past was attributed to several different factors: length of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection[3], alcohol and smoking[4], genetic characteristics of patients[5]. Lately, the distinctive role of menopause became apparent[2,6-8]. Soon after menopause liver disease becomes rapidly progressive and severe hepatic fibrosis develops[6-9], likely as a consequence of the rapid increase of inflammation as a direct consequence of estrogen deprivation[8,10]. In menopausal HCV-positive women there is a striking up-regulation of hepatic tumor necrosis factor-alfa (TNF-α), suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 (SOCS3), interleukin-6 (IL-6), whose levels correlate with higher necro-inflammation and with faster progression of liver fibrosis[9]. Not surprisingly, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was shown to exert a positive effect slowing down fibrosis progression[6]. Even more disappointing is the fact that menopausal HCV-positive women become also resistant to conventional antiviral therapy with Peg-Interferon-α + Ribavirin (PEG-IFNα/RBV): in our study of women with HCV-1 genotype menopause was the only independent factor predicting failure of dual antiviral therapy[9]. This finding was confirmed in a prospective cohort study aimed to evaluate viral and host factors influencing antiviral therapy: genotype 1 females over 50 years, had greatly reduced efficacy of interferon-based therapy[11]. Furthermore, the evaluation of our database for Hepatitis C showed that SVR rate after retreatment of menopausal women with HCV-1 genotype was very low, ranging from 5% after retreatment with dual PEG-IFNα/RBV in those having other unfavorable predictive factors like IL 28B (rs12979860) other than CC or high BMI[11-13] to 15% in those who had only menopause as risk factor (personal data).

We decided, therefore, to perform an exploratory study using the results from the previous retreatment studies as historical control to evaluate whether the addition of Boceprevir to standard PEG-IFN-α2b/RBV was able to increase the SVR rate in a difficult-to-treat cohort of menopausal HCV genotype 1 women with a previous PEG-IFN-α/RBV failure.

All patients gave written informed consent before starting the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria of Modena (EudraCT 2011-002459-33) and by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards of the other Institutions and was conducted in accordance with provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines (Clinical Trials ID: NCT01457937).

From December 2011 to June 2012 we screened 87 consecutive menopausal women with HCV genotype 1 infection and a documentation of a failed prior course of PEG-IFN-α/RBV for at least 12 wk, followed up in the out patients clinics of the Liver Units of Modena, Turin, Palermo and Naples.

Inclusion criteria included patients with relapse (undetectable HCV RNA level at the end of treatment, without subsequent attainment of a sustained virological response), prior partial-response (defined as decrease of HCV-RNA ≥ 2 log10 by week 12 of prior therapy but with detectable HCV-RNA throughout the course of therapy), or null-response (decrease of HCV-RNA ≤ 2 log10 by week 12 of prior therapy).

A liver biopsy within the last 2 years with histology consistent with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) and no other etiology was required. In subjects with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis, an ultrasound within 6 mo of the Screening Visit (or between Screening and Day 1) with no findings suspect for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was mandatory.

Exclusion criteria included co-infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis B virus (HBsAg positive), treatment with any investigational drug within 30 d of the randomization visit in this study, evidence of decompensated liver disease including history or presence of clinical ascites, bleeding varices, or hepatic encephalopathy, diabetic and/or hypertensive subjects with clinically significant ocular examination findings (like retinopathy, cotton wool spots, optic nerve disorder, retinal hemorrhage, or any other clinically significant abnormality), pre-existing psychiatric conditions, clinical diagnosis of substance abuse of the specified drugs within the specified timeframes, any known pre-existing medical condition that could interfere with the subject’s participation in and completion of the study, evidence of active or suspected malignancy, or a history of malignancy, within the last 5 years (except adequately treated carcinoma in situ and basal cell carcinoma of the skin). Further exclusion criteria included protocol-specified hematologic, biochemical, and serologic criteria: hemoglobin < 12 g/dL; neutrophils < 1500/mm3; platelets < 100000/mm3, direct bilirubin >1.5 × upper limit of normal (ULN), serum albumin < lower limit of normal (LLN), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) > 1.2 × ULN or < 0.8 × LLN of laboratory, serum creatinine > ULN of the laboratory reference, protocol-specified serum glucose concentrations, prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT) values > 10% above laboratory reference range, anti-nuclear antibodies > 1:320.

In this single-assignment, unblinded study we treated menopausal women with previous treatment failure to a prior course of PEG-IFN/RBV. The primary objective of retreatment was to verify whether a sustained virological response (SVR) (HCV RNA undetectable at 24 wk of follow-up) rate of at least 20% could be achieved with Boceprevir in menopausal women with chronic HCV genotype 1 with a previous failure of PEG IFN/Ribavirin. Secondary objective of this study was the evaluation of the percent of patients with negative HCV RNA at week 4 (rapid virological response, RVR), 8 (rapid virological response after BOC addition, RVR BOC), 12 (early virological response, EVR), or at the end-of-treatment (ETR) that reached SVR.

All patients received 4-wk lead-in with with PEG-IFN-α-2b at 1.5 μg/kg subcutaneously weekly, in combination with weight-based oral RBV at a total dose of 800 to 1400 mg per day according to body weight. In relapse and partial responder patients after 4 wk of lead-in, all patients received 32 wk of BOC 800 mg administered orally three times a day, in combination with PEG-IFN and RBV. These patients then received an additional 12 wk of PR only if HCV-RNA was positive by week 8 yet. In previous null-responders, after the lead-in phase, triple therapy with PEG-IFN/Ribavirin and Boceprevir was continued until week 48. All drugs were self-administered by the patients.

In all patients, if HCV RNA was detectable at week 12, treatment was stopped.

IL28B rs12979860 genotype was tested as already described[13].

Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to WHO grading system. The safety analyses included all subjects who receive at least one dose of study medication. Non severe hematological adverse events were managed by pharmacological dose reduction. In case of neutrophil count < 0.75 × 109/L, granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCS-F) was also used. In case of hemoglobin decrease < 10 g/dL, Ribavirin dose was reduced and/or erythropoietin administered.

Subjects having AEs were monitored with appropriate clinical assessments and laboratory tests, as determined by the investigator.

Analysis regarding the primary end-point included all patients who had received at least one dose of any study medication (intention-to-treat analysis). Our primary endpoint was attainment of sustained virological response, defined as undetectable circulating HCV RNA at week 24 of follow-up. Secondary end point was the identification of independent baseline and on-treatment SVR predictors.

To calculate sample size, we estimated to obtain at least a 20% increase in SVR vs historical controls with the same characteristic. Thus, with 80% power and a type 1 error set to 0.05, 49 subjects were required. A 15% excess of inclusions was allowed in order to compensate for withdrawals.

Dichotomous or continuous variables were compared with the Fisher exact test with mid-p correction or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney rank-sum test, respectively.

To assess the relationship between SVR and clinical and biochemical parameters, two multiple logistic regression models were used; the first assessed baseline variables only and the second assessed both baseline and on-treatment parameters. In the statistical model, the dependent variable was coded as 1 (present) vs 0 (absent). In all analyses, partial and null responders were considered together and referred to as non-responders. Variables associated with the dependent variable in univariate analyses (probability threshold, P < 0.10) were included in the multivariate regression model. The PASW Statistics 20 program (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for the analysis.

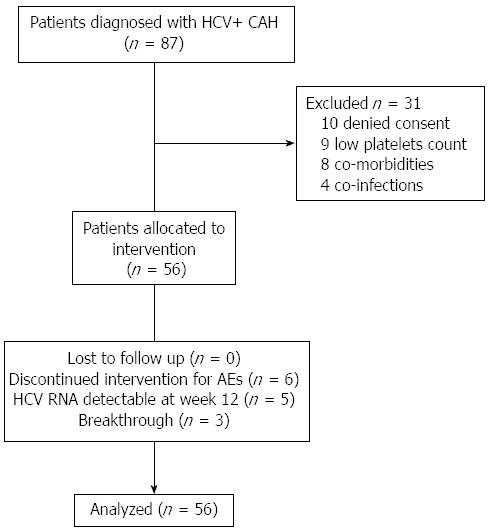

A total of 87 menopausal women with chronic Hepatitis C, genotype 1, with previous treatment failure to standard antiviral therapy, were evaluated (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the 56 enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. Thirty-eight women were from Northern Italy while 18 were from Southern Italy. There were no significant differences between them regarding previous response to antiviral therapy, percentage of patients with cirrhosis, IL28B genotype, basal BMI, duration of menopause, basal viral load. All patients completed follow up and were included in the analysis.

| Variables | |

| Mean age, mean ± SD (yr) | 56.8 ± 6.1 |

| Mean age at menopause, mean ± SD (yr) | 49.3 ± 4.3 |

| Time from menopause, mean ± SD (yr) | 11.4 ± 6.1 |

| Previous response n (%) | |

| Relapse | 29 (51.8) |

| Non response | 23 (41.1) |

| Null response | 4 (7.1) |

| Grading | 5.1 ± 2.4 |

| Staging | 2.3 ± 1.3 |

| Cirrhosis | 21 (37.5) |

| Stiffness (kPa) | 10.3 ± 7.1 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 26.2 ± 4.0 |

| Blood glucose, mean ± SD (mg/dL) | 101 ± 22 |

| Insulin_base (U/mL) | 9.9 ± 7.9 |

| HOMA score | 2.5 ± 1.5 |

| Blood Iron (μg/dL) | 128 ± 87 |

| Hb (g%) | 13.0 ± 2.2 |

| WBC (K/μL) | 4.9 ± 1.4 |

| Neutrophils (K/μL) | 2.5 ± 0.9 |

| Platelets (103/mm3) | 206 ± 78 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 36 ± 11 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| AST (IU/L) | 58 ± 24 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 66 ± 27 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 95 ± 28 |

| Gamma-GT (IU/L) | 45 ± 15 |

| HCV RNA (IU/mL, 103) | 1.440 ± 1.178 |

Mean age was 56.8 ± 6.1 years; mean menopausal duration was 11.4 ± 6.1 years (median 12.5 years). Mean BMI was 26.2 ± 4.0 (median 24.8). Four patients (7.1%) were previous null responders, 23 (41.1%) partial-responders and 29 (51.8%) relapsers. According to Metavir fibrosis score, 30/56 (54.0%) women had a score of 1 or 2, while 26/56 (46.0%) had a score of 3 or 4; of these, 21 (37.5%) had cirrhosis. Approximately 60% of patients had a high viral load (an HCV RNA level > 800000 IU per milliliter). Genotype 1b infection was predominant (52/56, 92.9%). IL28B rs12979860 genotype was available for 43 patients (9 CC, 26 TC, and 8 TT).

In the entire population, SVR was obtained in 25/56 (44.6%) patients. There was no significant difference between women of Northern and Southern origin in the SVR rate (44.7% vs 44.4%, respectively, P = 0.964).

After 4 wk of lead-in, none but two patients achieved RVR, while the HCV RNA drop of at least 1 log10 from baseline (IFN sensitivity) was obtained in 62% of patients. After Boceprevir addition, RVR BOC, EVR and ETR were obtained in 32/56 (57.1%), 41/56 (73.2%), and 42 (75.0%) respectively. Of these, 53.8%, 52.0%, and 52.0%, respectively, achieved SVR.

Fourteen patients (25.0%) stopped therapy [6/14 (43%) for intolerance, 5/14 (36%) for HCV RNA detectability at week 12; 3/14 (21%) for viral breakthrough]. All experienced a virological relapse.

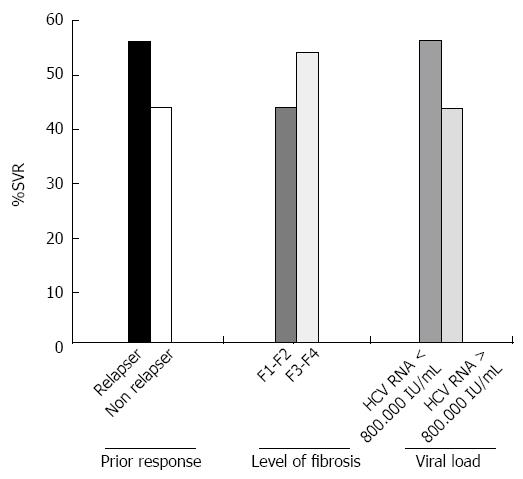

The rate of sustained virological response among patients with prior relapse or non-response was 55% and 41% respectively (P = 0.250). No significant correlation was present between SVR and high viral load (HCV RNA > 800.000 IU/mL: P = 0.597) or IL28 status (P = 0.333). Patients with IFN sensitivity had significantly higher SVR rates compared patients with IFN insensitivity (57.1% vs 26.3%, P = 0.030). Level of fibrosis did not negatively influence the SVR rate, which occurred in 44% of women with F0-F2 vs 54% of those with F3-F4 fibrosis (P = 0.488) nor was the presence of cirrhosis (presence of cirrhosis vs. absence: P = 0.485). Figure 2 depicts SVR rates according to the pattern of prior response, severity of fibrosis and baseline viral load.

At univariate analysis for baseline predictors of SVR, none of the clinical and biochemical parameters but previous response to antiviral therapy (OR = 2.662, 95%CI: 0.957-6.881, P = 0.043) was related with SVR. When taking into consideration also “on treatment” factors, 1 log10 HCV RNA decline at week 4 (3.733, 95%CI: 1.676-12.658, P = 0.034) and achievement of RVR BOC (7.347, 95%CI: 2.156-25.035, P = 0.001) were significantly related with SVR, although RVR BOC only (6.794, 95%CI: 1.596-21.644, P = 0.010) maintained significance at multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2).

| Variables | Univariate analysis OR (95% CI) | P value | Multivariate analysis OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 1.006 (0.916-1.105) | 0.900 | ||

| Age at menopause | 1.150 (0.931-1.450) | 0.195 | ||

| Previous response | 2.662 (0.957-6.881) | 0.043 | 2.927 (0.931-9.206) | 0.066 |

| Histological grading | 0.894 (0.605-1.322) | 0.576 | ||

| Histological staging | 0.982 (0.586-1.645) | 0.946 | ||

| Fibrosis | 1.667 (0.528-5.265) | 0.384 | ||

| Liver stiffness | 0.986 (0.895-1.086) | 0.774 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 1.111 (0.155-7.974) | 0.917 | ||

| BMI | 1.000 (0.825-1.212) | 1.000 | ||

| HCV RNA > 800.000 IU/mL | 0.519 (0.120-2.248) | 0.381 | ||

| RVR | 1.200 (0.070-20.429) | 0.900 | ||

| 1 log decline at week 4 | 3.733 (1.676-12.658) | 0.034 | 0.961(0.194-4.757) | 0.961 |

| RVR BOC | 7.347 (2.156-25.035) | 0.001 | 6.794 (1.596-21.644) | 0.010 |

| ALT (IU/mL) | 0.996 (0.977-1.014) | 0.645 | ||

| Platelets (× 103/mm3) | 1.000 (1.000-1.000) | 0.165 | ||

| HOMA | 0.907 (0.533-1.544) | 0.719 |

Anaemia and neutropenia were managed with Erythropoietin and Granulokine supplementation, respectively: only six patients discontinued therapy.

The treatment was well tolerated, with low rates of severe adverse events. Fatigue and nausea were the most common adverse events. Hemoglobin levels decreased significantly at all-time points, without requiring the introduction of erythropoietin before week 6 (i.e., 2 wk following the addition of boceprevir). Conversely, the neutrophil count reduction required Granulokine supplementation already at week 2. Anemia was successfully managed with erythropoietin supplementation, as neutropenia with Granulokine supplementation. The supplementation of both Erythropoietin and Granulokine was necessary to preserve the full treatment doses. None of the patients experienced skin problems; dysgeusia was frequent, but no patient discontinued therapy due to this event (Table 3).

| Event | |

| Death, n | 0 |

| Drug Discontinuation due to AE | 6 (10) |

| Dose Modification due to AE | 8 (14) |

| Any life-threatening adverse event, n | 0 |

| Any serious adverse event | 2 (4) |

| Hematologic event Reduced neutrophil count < 750 per mm3 < 500 per mm3 | 14 (25) 8 (15) |

| Mean change in hemoglobin from baseline (g/dL) | |

| At wk 12 | -1.2 |

| At wk 24 | -2.2 |

| At wk 48 | -3.3 |

| Erythropoietin use | 20 (35) |

| Transfusion | 1 (1.8) |

| Common adverse event | |

| Nausea | 24 (43) |

| Anemia | 23 (41) |

| Dysgeusia | 20 (36) |

| Fatigue | 18 (32) |

| Rash | 6 (11) |

In this study on a cohort of difficult-to-treat genotype 1 CHC patients (menopausal females, failure to a previous course of PEG-IFN/RBV, high prevalence of F3-F4 fibrosis) we showed that retreatment with a BOC-based TT regimen leads to SVR in about 45% of cases, RVR BOC being the only independent predictor of SVR.

The achievement of SVR in a great proportion of patients gives BOC-based therapy a relevant option for this group of difficult-to-treat patients, where a deferral strategy towards IFN-free regimens should be carefully evaluated due to the rapid progression of the liver diseases related to the menopausal status.

Menopausal women with chronic HCV genotype 1 infection are patients experiencing an utmost resistance to antiviral therapy with PEG-IFN-α and Ribavirin occurring at and soon after the onset of menopause[9]. This issue could be probably further amplified in patients who failed a previous treatment with PEG-IFN and Ribavirin. In this clinical context several studies, not stratified for gender and menopausal status, were not able to obtain more than a 3%-21% SVR despite employing PEG-IFN/RBV-based treatment schedules with higher PEG-IFN-α dosages or longer period of treatment than routinely used[14-18]. As in all the above studies, our cohort of menopausal patients with a previous failure to dual antiviral therapy exhibited a marked lack of sensitivity toward interferon, i.e., none but two patients achieved RVR after the 4-wk lead-in, and a substantial proportion displayed less than 1 log decline of viral load. Despite the this occurrence, the addition of Boceprevir determined a striking effect: viral load became undetectable in almost 60% of patients after 4 wk and in more than 70% at week 12, and finally SVR was obtained in 45% of women. The SVR we obtained is slightly lower than that reported in the study by Bacon et al[17] who, with a similar treatment regimen, obtained a 59% and 66% depending on the treatment schedule. It should, however, be underlined that the population undergoing treatment in the Bacon study was characterized by much more favorable characteristics in term of response to antiviral therapy like younger age and less advanced disease than ours. A recent paper by Vierling et al[19] reported higher SVR rates with BOC re-treatment. Enrolled patients belonged to control arm of 4 Boceprevir studies (SPRINT-2, RESPOND-2, SPRINT-1, or Protocol 05685)[17,20-22] and had not achieved SVR. They were enrolled soon (< 2 wk) after a failed PEG-IFN-α/RBV course at least 12 wk that however, in about 40% of patients, had lasted 48 wk. This makes the results scarcely comparable with the other re-treatment studies and ours as the patients were exposed in a restricted period of time to PEG-IFN-α/RBV for more than double the usual duration of therapy. The results reported by Flamm et al[23] of retreatment of patients previously treated with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection are consistent with ours: subjects who had had poor response to interferon therapy (< 1 log10 decline in HCV RNA at week 4), had only a 39% SVR. Interestingly, none of the patients with less than 1 log decline had SVR when retreated with dual PEG-IFN/RBV. As a general remark, in none of the previously cited retreatment studies was the stratification by menopausal status available.

Another relevant finding of our study lies in the identification of RVR BOC as the only independent predictor of SVR. This result raises attention for relevant practical issues in the management of this difficult-to-treat group of patients, when RVR BOC occurs, the pattern of previous failure to dual therapy does not significantly affect the likelihood of SVR to BOC-based TT. Second, although 1 log10 decline of viral load after 4 wk of dual therapy identified patients at higher SVR likelihood, it was not confirmed as independently associated with SVR at multivariate analysis. Third, none of the other factors that are traditionally associated with achievement of a sustained virological response (i.e., low viral load at baseline, absence of fibrosis or cirrhosis, IL 28B genotype, > 1 log10 decrease in HCV RNA)[24] was independently related with SVR. It is of note that the relevance of RVR BOC as predictor of SVR has been identified in other studies of difficult-to-treat population like patients with cirrhosis[25,26].

The main limitation of this study lies in the potentially limited external validity of the results for different populations and settings. Our study included a cohort of Italian patients enrolled at tertiary care centers, who may be different from general population, in terms of both metabolic features and severity of liver disease, limiting the broad application of the results.

In conclusion, Boceprevir addition to standard PEG-IFN-α/RBV therapy was effective in achieving SVR in about 50% of menopausal women with chronic hepatitis C, genotype 1, who had failed SVR with prior PEG-IFN-α/RBV treatment. Most importantly, Boceprevir-based triple therapy success rate was not influenced by pattern of previous response to DT or by the severity of liver fibrosis while RVR BOC was the only independent predictor of SVR. This opens a relevant possibility for patients who are at high risk of a rapid progression toward cirrhosis and/or decompensation.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a leading cause of chronic liver disease. In menopausal women, the disease becomes much more rapidly progressing than during reproductive age, severe fibrosis develops, and response to antiviral therapy becomes low.

The therapeutic options for HCV are rapidly growing. New drugs will be, however, extremely expensive and the use of the best cost-effective options should be pursued in order to offer treatment to the largest number of patients.

The results support the concept that triple antiviral treatment with PEG IFN/Ribavarin and Boceprevir is able to obtain a striking improvement in the SVR rate of menopausal women with HCV with previous treatment failure.

The management of patients who do not achieve a viral response has always been challenging. The results of this study support the efficacy, safety and tolerability of PEG IFN/Ribavirin and Boceprevir in a high percentage of previous non responders to PEG IFN/Ribavirin thus offering immediate cure to patients otherwise likely to rapidly progress toward severe fibrosis.

SVR indicates sustained virological response, i.e., viral clearance for more than 24 wk after treatment.

In the manuscript the authors present data showing that the difficult to treat population of menopausal women display improved treatment results by the inclusion of boceprevir. The manuscript is clearly presented and generally well-written, although it should be edited once more by the authors before publishing. HCV triple therapy including either telaprevir or boceprevir is now the current standard of care therapy for HCV infection, though this will soon change to “next generation” antivirals. The population numbers of the current study are limited to 56, and would be strengthened by expanding the study to a larger population.

P- Reviewer: Bellanti F, Felmlee DJ, Gherlan GS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Floreani A, Cazzagon N, Boemo DG, Baldovin T, Baldo V, Egoue J, Antoniazzi S, Minola E. Female patients in fertile age with chronic hepatitis C, easy genotype, and persistently normal transaminases have a 100% chance to reach a sustained virological response. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:997-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Villa E, Vukotic R, Cammà C, Petta S, Di Leo A, Gitto S, Turola E, Karampatou A, Losi L, Bernabucci V. Reproductive status is associated with the severity of fibrosis in women with hepatitis C. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | de Torres M, Poynard T. Risk factors for liver fibrosis progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol. 2003;2:5-11. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Missiha SB, Ostrowski M, Heathcote EJ. Disease progression in chronic hepatitis C: modifiable and nonmodifiable factors. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1699-1714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Estrabaud E, Vidaud M, Marcellin P, Asselah T. Genomics and HCV infection: progression of fibrosis and treatment response. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1110-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Di Martino V, Lebray P, Myers RP, Pannier E, Paradis V, Charlotte F, Moussalli J, Thabut D, Buffet C, Poynard T. Progression of liver fibrosis in women infected with hepatitis C: long-term benefit of estrogen exposure. Hepatology. 2004;40:1426-1433. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Codes L, Asselah T, Cazals-Hatem D, Tubach F, Vidaud D, Paraná R, Bedossa P, Valla D, Marcellin P. Liver fibrosis in women with chronic hepatitis C: evidence for the negative role of the menopause and steatosis and the potential benefit of hormone replacement therapy. Gut. 2007;56:390-395. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Codes L, Matos L, Paraná R. Chronic hepatitis C and fibrosis: evidences for possible estrogen benefits. Braz J Infect Dis. 2007;11:371-374. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Villa E, Karampatou A, Cammà C, Di Leo A, Luongo M, Ferrari A, Petta S, Losi L, Taliani G, Trande P. Early menopause is associated with lack of response to antiviral therapy in women with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:818-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pfeilschifter J, Köditz R, Pfohl M, Schatz H. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:90-119. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Di Marco V, Covolo L, Calvaruso V, Levrero M, Puoti M, Suter F, Gaeta GB, Ferrari C, Raimondo G, Fattovich G. Who is more likely to respond to dual treatment with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C? A gender-oriented analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:790-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cariani E, Villa E, Rota C, Critelli R, Trenti T. Translating pharmacogenetics into clinical practice: interleukin (IL)28B and inosine triphosphatase (ITPA) polymophisms in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:1247-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cariani E, Critelli R, Rota C, Luongo M, Trenti T, Villa E. Interleukin 28B genotype determination using DNA from different sources: A simple and reliable tool for the epidemiological and clinical characterization of hepatitis C. J Virol Methods. 2011;178:235-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jensen DM, Marcellin P, Freilich B, Andreone P, Di Bisceglie A, Brandão-Mello CE, Reddy KR, Craxi A, Martin AO, Teuber G. Re-treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C who do not respond to peginterferon-alpha2b: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:528-540. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bacon BR, Shiffman ML, Mendes F, Ghalib R, Hassanein T, Morelli G, Joshi S, Rothstein K, Kwo P, Gitlin N. Retreating chronic hepatitis C with daily interferon alfacon-1/ribavirin after nonresponse to pegylated interferon/ribavirin: DIRECT results. Hepatology. 2009;49:1838-1846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yee HS, Currie SL, Tortorice K, Cozen M, Shen H, Chapman S, Cunningham F, Monto A. Retreatment of hepatitis C with consensus interferon and ribavirin after nonresponse or relapse to pegylated interferon and ribavirin: a national VA clinical practice study. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2439-2448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Goodman ZD, Sings HL, Boparai N. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1306] [Cited by in RCA: 1308] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Leevy CB. Consensus interferon and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C who were nonresponders to pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1961-1966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vierling JM, Davis M, Flamm S, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Yoshida EM, Galati J, Luketic V, McCone J, Jacobson I. Boceprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection in patients with prior treatment failure to peginterferon/ribavirin, including prior null response. J Hepatol. 2014;60:748-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Poordad F, McCone J, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1996] [Cited by in RCA: 1981] [Article Influence: 141.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML, Muir AJ, Galler GW, McCone J, Nyberg LM, Lee WM, Ghalib RH, Schiff ER. Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:580-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 894] [Cited by in RCA: 886] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Pound D, Davis MN, Galati JS, Gordon SC, Ravendhran N. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:705-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Flamm SL, Lawitz E, Jacobson I, Bourlière M, Hezode C, Vierling JM, Bacon BR, Niederau C, Sherman M, Goteti V. Boceprevir with peginterferon alfa-2a-ribavirin is effective for previously treated chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:81-87.e4; quiz e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Poordad F, Bronowicki JP, Gordon SC, Zeuzem S, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski MS, Poynard T, Morgan TR, Molony C, Pedicone LD. Factors that predict response of patients with hepatitis C virus infection to boceprevir. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:608-18.e1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bruno S, Vierling JM, Esteban R, Nyberg LM, Tanno H, Goodman Z, Poordad F, Bacon B, Gottesdiener K, Pedicone LD. Efficacy and safety of boceprevir plus peginterferon-ribavirin in patients with HCV G1 infection and advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;58:479-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 535] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Bronowicki JP, Manns MP, Bacon BR, Esteban R, Flamm SL, Kwo PY, Pedicone LD. Safety and efficacy of boceprevir/peginterferon/ribavirin for HCV G1 compensated cirrhotics: meta-analysis of 5 trials. J Hepatol. 2014;61:200-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |