Published online Nov 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16359

Revised: May 14, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Published online: November 21, 2014

Processing time: 248 Days and 6.1 Hours

Primary malignant tumors of the small intestine are rare, comprising less than 2% of all gastrointestinal tumors. An 85-year-old woman was admitted with fever of 40 °C and marked abdominal distension. Her medical history was unremarkable, but blood examination showed elevated inflammatory markers. Abdominal computed tomography showed a giant tumor with central necrosis, extending from the epigastrium to the pelvic cavity. Giant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the small intestine communicating with the gastrointestinal tract or with superimposed infection was suspected. Because no improvement occurred in response to antibiotics, surgery was performed. Laparotomy revealed giant hemorrhagic tumor adherent to the small intestine and occupying the peritoneal cavity. The giant tumor was a solid tumor weighing 3490 g, measuring 24 cm × 17.5 cm × 18 cm and showing marked necrosis. Histologically, the tumor comprised spindle-shaped cells with anaplastic large nuclei. Immunohistochemical studies showed tumor cells positive for vimentin, CD31, and factor VIII-related antigen, but negative for c-kit and CD34. Angiosarcoma was diagnosed. Although no postoperative complications occurred, the patient experienced enlargement of multiple metastatic tumors in the abdominal cavity and died 42 d postoperatively. The prognosis of small intestinal angiosarcoma is very poor, even after volume-reducing palliative surgery.

Core tip: Angiosarcoma represents 1%-2% of soft-tissue sarcomas and most frequently occurs in the subcutis. This tumor may affect internal organs such as the heart, liver, and spleen, and only rarely emerges in the gastrointestinal tract. Details of angiosarcoma of the small intestine are thus particularly scarce. We encountered a case of small intestinal angiosarcoma showing rapid tumor growth. We speculate that the giant tumor became hypoxic due to ischemia, resulting in tumor necrosis and perforation. Postoperative prognosis was very poor, and a multidisciplinary approach to establishing optimal treatment is warranted.

- Citation: Takahashi M, Ohara M, Kimura N, Domen H, Yamabuki T, Komuro K, Tsuchikawa T, Hirano S, Iwashiro N. Giant primary angiosarcoma of the small intestine showing severe sepsis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(43): 16359-16363

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i43/16359.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16359

Angiosarcoma represents 1%-2% of soft-tissue sarcomas and most frequently occurs in the subcutis. This tumor may affect internal organs such as the heart, liver, and spleen, and only rarely involves the gastrointestinal tract. Details of angiosarcoma occurring in the small intestine are therefore particularly valuable. This report describes the case of a patient with primary giant angiosarcoma of the small intestine.

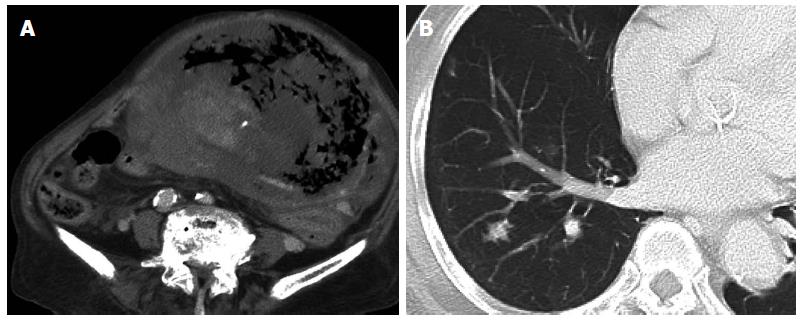

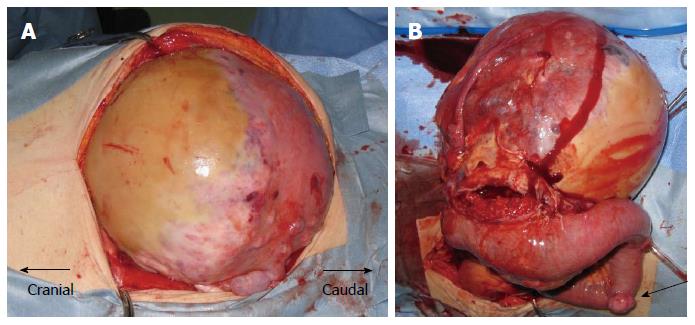

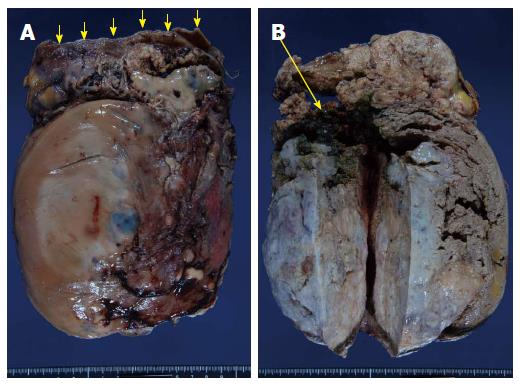

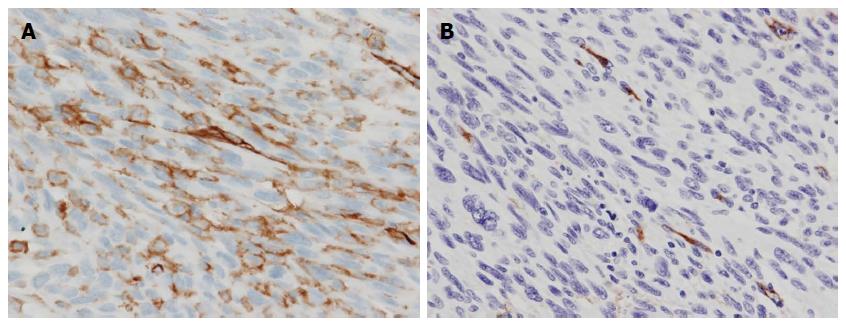

An 85-year-old woman with no relevant past history was admitted to our institution with a fever of 40 °C and marked abdominal distention. Blood examination showed: white blood cell count, 25200/μL; hemoglobin, 7.8 g/dL; platelets, 328000/μL; C-reactive protein, 30.07 mg/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase, 505 IU/L. Tumor markers were not elevated. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a giant tumor occupying from the epigastrium to the pelvic cavity and displaying central necrosis with multiple lung metastasis (Figure 1A, B). Because the feeding artery for the tumor was the superior mesenteric artery, giant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the small intestine was suspected. T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showed a giant, low-intensity, enhanced tumor including an air level. Blood culture was positive. Because no improvement of sepsis was achieved despite administration of empiric therapy with antibiotics (doripenem hydrate), surgery was performed for infection control on hospital day 3. Intraoperatively, a giant hemorrhagic, flexible tumor arising from the small intestine was seen occupying the peritoneal cavity (Figure 2A). Multiple small tumors were identified at other sites of the small intestine and abdominal wall (Figure 2B). A giant tumor in the small intestine was resected along with 15 cm of small intestine, with reconstruction by functional end-to-end anastomosis. A few small tumors in other areas of the small intestine and peritoneum were also resected, but many tumors remained (R2). The operation time was 85 min. Total intraoperative blood loss was 770 mL. The giant tumor was a solid tumor weighing 3490 g, measuring 24 cm × 17.5 cm × 18 cm and showing marked internal necrosis and hemorrhage (Figure 3A). The cut surface showed a large amount of hemorrhage in the small intestine flowing from the giant tumor (Figure 3B). Histological examination of the tumor revealed spindle-shaped cells with large, anaplastic nuclei. These tumor cells showed proliferation in a herringbone pattern and a partial palisade arrangement. Multinucleated giant cells were sometimes observed. Immunohistochemical studies showed positive results for CD31, vimentin, and factor VIII-related antigen (Figure 4A and B), but negative results for CD34, c-kit, CAM5.2, AE1/AE3, desmin, α-smooth muscle actin and HMB45. Based on these pathological findings, angiosarcoma of the small intestine was diagnosed. The Ki67 labeling index was about 50%, indicating a highly malignant tumor. The resected small tumors of the intestine and peritoneum showed the same histological findings and were diagnosed as tumor dissemination. No postoperative complications such as leakage or sepsis were encountered, but disseminated nodules remaining in the abdominal cavity showed rapid growth after the operation. On postoperative day 22, results of blood examination showed obstructive jaundice and CT indicated an increase in tumor size. The general state of the patient continued to deteriorate and she died on postoperative day 42. After obtaining consent from the family, autopsy was performed. Almost all of the abdominal organs showed involvement by disseminated necrotic nodules, up to 5 cm in maximum diameter. The autopsy revealed multiple tumors in the intestines, peritoneum, lungs and pleura.

Primary malignant tumors of the small intestine are rare, comprising less than 2% of all gastrointestinal tumors[1]. Among these, the most frequent are malignant carcinoid, adenocarcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma[2].

Angiosarcomas are characterized by proliferation of tumor cells with vascular endothelial features. These very rare neoplasms account for only 1%-2% of all soft-tissue sarcomas. Most are identified on the scalp, skin and soft tissues of the head and neck region, and are extremely rare in the gastrointestinal tract[3]. Involvement of internal organs has been reported, predominantly in the liver and spleen[4,5]. To the best of our knowledge, only 12 cases of primary angiosarcoma of the small intestine have been reported in the English literature since 2000 (Table 1)[6].

| Author | Patient (age/sex) | Tumor manifestation | Tumor size (cm) | Histology | Symptoms | Therapy | Outcome | |

| Report year | ||||||||

| 1 | Delvaux et al | 67/M | Jejunum ileum | 2.2 | Epithelioid | Melena | Resection | Died 3 mo after |

| 2000 | Abdominal pain | Operation | ||||||

| 2 | Fraiman et al | 85/M | Small intestine | 8-10 | High-grade | Weight loss | Resection | Survived |

| 2003 | Decreased appetite | Chemotherapy | At least 1 yr | |||||

| 3 | Keleman et al | 76/M | Ileum | NA | Mixed,well-differentiated and epithelioid | Abdominal pain | Resection | Died 9 d after |

| 2004 | Poor appetite | Operation | ||||||

| 4 | Allison et al | 84/F | Jejunum | NA | Epithelioid | Anemia | NA | Died 17 mo after |

| 2004 | Shortness of breath | Diagnosis | ||||||

| 5 | Allison et al | 47/M | Jejunum | NA | Epithelioid | Anemia | NA | Died 4 mo after |

| 2004 | Shortness of breath | Diagnosis | ||||||

| 6 | Butrón Vila et al | 70/M | Ileum | 5 | Mixed, well-differentiated and epithelioid | Abdominal pain | Resection | Survived |

| 2005 | Vomiting | Chemotherapy | At least 4 yr | |||||

| Radiation | ||||||||

| 7 | Al Ali et al | 87/M | Jejunum (and duodenum) | NA | Epithelioid | Lethargy, weakness | Endoscopy, | Died 6 wk after |

| 2006 | Chest pain | Argon Plasma coagulation | Diagnosis | |||||

| 8 | Policarpio-Nicolas et al | 51/F | Terminal ileum | NA | Well-differentiated | Decreased appetite | Resection and | Died 10 mo after |

| 2006 | Vague abdominal pain | Palliative care | Operation | |||||

| 9 | Grewal et al | 73/M | Jejunum (and duodenum) | NA | Epithelioid | Weakness, anemia | Resection | Died 4 mo after |

| 2008 | Melena | Operation | ||||||

| 10 | Turan et al | NA/M | Jejunum | NA | NA | Acute abdominal signs | Resection | Died 3 yr after |

| 2010 | Chemotherapy | Operation | ||||||

| 11 | Zacarias Föhrding et al | 84/M | Small intestine | NA | Epithelioid | Anemia, melena | Resection | Died from intracranial |

| 2012 | Hemorrhage | |||||||

| 12 | Our case | 85/F | Small intestine | 24 × 17.5 × 18 | High-grade | Sepsis | Resection | Died 42 d after |

| operation |

The precise predisposing factors for angiosarcoma remain unknown, although associations with exposure to polyvinyl chloride and radiation have been identified[3]. The patient in the present case had not been exposed to either polyvinyl chloride or radiation.

Angiosarcomas show a double growth pattern, with vasoformative and/or solid expansion[7]. The vasoformative growth pattern can range from well-formed vessels over vascular spaces with papillary projections to slit-like anastomosing vascular channels. On the other hand, the solid growth pattern consists of two cell types: sheets of spindle-shaped cells; or large, polygonal epithelioid-type cells. The mitotic rate is also high. In the present case, angiosarcoma showed a solid growth pattern based on the pathological findings. Most reported cases of angiosarcoma appear to initially present with bleeding or anemia and are found at a size less than 10 cm, mainly due to the fragile nature of the tumor and rich vasoformative components. However, in the present case, the angiosarcoma showed dominance of the solid growth pattern with many juvenile cells and the speed of tumor growth was thus remarkable. We speculate that the giant tumor became hypoxic due to ischemia, resulting in tumor necrosis. Furthermore, with the advance of tumor necrosis, the wall of the small intestine became weakened and perforated. We suspected the presence of sepsis, since the tumor showed communication with the tract of the small intestine, presumably due to the above-mentioned mechanisms. Most patients with angiosarcoma of the small bowel present with abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea[8]. To the best of our knowledge, only two prior reports have described intestinal perforation occurring with abdominal angiosarcoma[9,10], and no prior reports have presented giant abdominal angiosarcoma (diameter > 20 cm). This rare case suggests the diversity of symptoms and clinical severity of poorly differentiated angiosarcoma in the small intestine.

Pathological diagnosis of angiosarcoma may be a challenge, and immunohistological markers are needed to differentiate this tumor from poorly differentiated carcinomas[3] and sarcomas. Immunohistochemical analysis for the expression of endothelial markers, CD31, CD34, and factor VIII-associated antigen is crucial[6]. In this case, the cytoplasm of the main giant tumor and other resected small tumors was positive for CD31 and vimentin and very focally positive for factor VIII-related antigen. Both types of tumor cells were negative for CD34. Histopathologically, differential diagnoses thus included fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, GIST, malignant melanoma and angiosarcoma. However, the results of immunohistochemical study excluded all of these tumors, with the exception of angiosarcoma.

Outcomes for patients with intestinal angiosarcoma are extremely poor, with most not surviving long into the postoperative period or dying within a few months of diagnosis[11]. In the present case, tumor proliferation was extremely rapid, and the patient died on postoperative day 42. No curative therapies have yet been established for gastrointestinal angiosarcoma.

Chemotherapy with doxorubicin and weekly paclitaxel has been used for metastatic angiosarcoma and seems to provide longer progression-free survival[12,13]. Adjuvant thalidomide therapy has recently been used as an experimental measure, as some studies have shown this approach to be beneficial in patients with cutaneous angiosarcoma. Almost no statements have been made regarding the efficacy of chemotherapy for small intestinal angiosarcoma. A multidisciplinary approach to establishing optimal treatment is thus warranted.

In conclusion, we have reported a rare case of giant angiosarcoma (diameter > 20 cm) of the small intestine that resulted in perforation from necrosis caused by expansive solid-type tumor growth. No curative therapies have yet been established for this pathology, and outcomes for small intestinal angiosarcoma remain very poor, even after palliative surgery to achieve volume reduction.

Main symptom of this present case was high fever.

Main clinical findings of this present case were high fever and abdominal distention.

Preoperatively, we suspected giant gastrointestinal stromal tumor from the computed tomography (CT).

This present case showed elevating inflammatory reaction at the blood examination.

The CT showed giant abdominal tumor displaying central necrosis and multiple lung metastatic tumors.

Immunohistochemical studies positive results for CD31, vimentin and factor VIII-related antigen.

The treatment for this present case was only palliative surgery. Chemotherapy or radiotherapy were not performed.

Small intestinal angiosarcoma is very rare. Especially, giant small intestinal angiosarcoma was not reported. This present case was first report of giant small intestinal angiosarcoma over 20 cm. In this report, the relation between a tumor growth pattern and tumor necrosis is discussed. This differs from past articles.

Every terms in this paper is common and not necessary to explain.

The authors experienced a case of giant angiosarcoma of the small intestine resulted in perforation. Outcomes for small intestinal angiosarcoma remain very poor, even after palliative surgery.

In this case report, the authors reported a very rare case of giant angiosarcoma of small intestine showing sepsis. They also reported that sepsis was presented since necrotic portion of tumor had communication with tract of small intestine. This present case was not being able to be performed adjuvant therapy.

P- Reviewer: Kwon WY S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43-66. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chami TN, Ratner LE, Henneberry J, Smith DP, Hill G, Katz PO. Angiosarcoma of the small intestine: a case report and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:797-800. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Khalil MF, Thomas A, Aassad A, Rubin M, Taub RN. Epithelioid Angiosarcoma of the Small Intestine After Occupational Exposure to Radiation and Polyvinyl Chloride: A case Report and Review of Literature. Sarcoma. 2005;9:161-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hsu JT, Chen HM, Lin CY, Yeh CN, Hwang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF. Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen. J Surg Oncol. 2005;92:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hsu JT, Lin CY, Wu TJ, Chen HM, Hwang TL, Jan YY. Splenic angiosarcoma metastasis to small bowel presented with gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6560-6562. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Zacarias Föhrding L, Macher A, Braunstein S, Knoefel WT, Topp SA. Small intestine bleeding due to multifocal angiosarcoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6494-6500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Delvaux V, Sciot R, Neuville B, Moerman P, Peeters M, Filez L, Van Beckevoort D, Ectors N, Geboes K. Multifocal epithelioid angiosarcoma of the small intestine. Virchows Arch. 2000;437:90-94. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Siderits R, Poblete F, Saraiya B, Rimmer C, Hazra A, Aye L. Angiosarcoma of small bowel presenting with obstruction: novel observations on a rare diagnostic entity with unique clinical presentation. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2012;2012:480135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kelemen K, Yu QQ, Howard L. Small intestinal angiosarcoma leading to perforation and acute abdomen: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:95-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hwang TL, Sun CF, Chen MF. Angiosarcoma of the small intestine after radiation therapy: report of a case. J Formos Med Assoc. 1993;92:658-661. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Fraiman G, Ganti AK, Potti A, Mehdi S. Angiosarcoma of the small intestine: a possible role for thalidomide? Med Oncol. 2003;20:397-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Penel N, Italiano A, Ray-Coquard I, Chaigneau L, Delcambre C, Robin YM, Bui B, Bertucci F, Isambert N, Cupissol D. Metastatic angiosarcomas: doxorubicin-based regimens, weekly paclitaxel and metastasectomy significantly improve the outcome. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:517-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Italiano A, Cioffi A, Penel N, Levra MG, Delcambre C, Kalbacher E, Chevreau C, Bertucci F, Isambert N, Blay JY. Comparison of doxorubicin and weekly paclitaxel efficacy in metastatic angiosarcomas. Cancer. 2012;118:3330-3336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |