Published online Nov 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16252

Revised: June 9, 2014

Accepted: July 16, 2014

Published online: November 21, 2014

Processing time: 226 Days and 6.2 Hours

AIM: To analyze the clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors of rectal neuroendocrine tumors.

METHODS: The records of 48 patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors who were treated at the Cancer Institute and Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, from March 2004 to September 2009 were retrospectively reviewed. The clinicopathological data were extracted and analyzed, and patients were followed-up by telephone or follow-up letter to determine their survival status. Follow-up data were available for all 48 patients. Uni- and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to determine the prognostic factors significantly associated with overall survival.

RESULTS: The tumors occurred mostly in the middle and lower rectum, and the most prominent symptoms experienced by patients were hematochezia and diarrhea. The median distance between the tumors and the anal edges was 5.0 ± 2.257 cm, and the median diameter of the tumors was 0.8 ± 1.413 cm. The major pathological type was a typical carcinoid tumor, which accounted for 93.8% (45/48) of patients. Tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stages I, II, III and IV tumors accounted for 78.8%, 3.9%, 9.6% and 7.7% of patients, respectively. The main treatment method, in 72.9% (35/48) of patients, was transanal extended excision. The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of the whole group of patients were 100%, 93.7%, and 91.3%, respectively. Univariate analysis showed that age (P = 0.032), tumor diameter (P < 0.001), histological type (P < 0.001), TNM stage (P < 0.001), and surgical approach (P = 0.002) were all prognostic factors. On multivariate analysis, only the pathological type was shown to be an independent prognostic factor (HR = 2.797, 95%CI: 1.676-4.668, P = 0.004).

CONCLUSION: In patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors, TNM stage I is the most common stage found, and lymph node or distant metastases are rarely seen. The pathological type of the tumor is an independent prognostic factor.

Core tip: An analysis of the clinicopathologic characteristics of a group of 57 patients with pathologically-confirmed diagnoses of rectal neuroendocrine tumors showed that these tumors mostly occur in the middle and lower rectum. The most common tumor-node-metastasis stage found was stage I, and lymph node or distant metastases were rarely seen. The major pathological type was a typical carcinoid tumor. Transanal extended excisions generally produced satisfactory curative effects, and the 5-year survival rate was as high as 88.6%. A multivariate analysis of the patient and tumor characteristics indicated that the pathological type is an independent prognostic factor.

- Citation: Chi Y, Du F, Zhao H, Wang JW, Cai JQ. Characteristics and long-term prognosis of patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(43): 16252-16257

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i43/16252.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16252

Rectal neuroendocrine tumors are rare with an incidence of about 3.08 per 100000 person-years[1], but there has been a slow upward trend in their incidence since the 1990s[2,3]. They are considered to be a type of tumor with indolent biological behavior and a relatively favorable prognosis[4]. In 2003, Modlin et al[1] reported that the 5-year survival rate was 88.3%. However, in recent years, studies have found that typically malignant biological behavior, such as lymph node and distant metastases, have appeared in patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Bernick et al[5] reported that the 3-year survival rate in a group of patients with colorectal neuroendocrine tumors was only 13%. This indicates significant differences among individuals which has a significant effect on the prognosis of these patients, and consequently tailored treatments are warranted[6].

This study was undertaken to analyze the clinicopathologic characteristics of rectal neuroendocrine tumors in a group of patients seen at our institute between March 2004 and September 2009, and to identify the prognostic factors for their survival.

The study was a retrospective analysis of 48 patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors in whom a definite pathological diagnosis had been made at the Cancer Institute and Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing during the period March 2004 to September 2009. The patients included 31 males and 17 females, with a median age of 53.5 years (range: 27-77 years). The tumors were staged via the TNM staging standard for rectal neuroendocrine tumors which was updated by the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society in 2007[7].

The survival times of all patients were calculated from the date a definite diagnosis of a rectal neuroendocrine tumor was made. The last patient follow-up visit was on June 15, 2012. Follow-ups included telephone calls and letters and repeat visits by patients to the hospital. The median follow-up time for all patients in the study group was 58 mo (range: 12-98 mo).

Patient data were analyzed statistically using SPSS® version 17.0 statistical software. The Kaplan-Meier method was applied for the survival analysis. A log-rank test was used for a univariate analysis of prognostic factors, and a Cox proportional hazard model was used for a multivariate analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All patients underwent a colonoscopy. The most common symptoms in the 48 patients evaluated were hematochezia in 33.3% (16/48) and diarrhea in 22.9% (11/48). None of the patients exhibited carcinoid syndrome. The median distance between the tumors and anal edges was 5.0 ± 2.257 cm. Patients with a distance between the tumor and the anal edge ≤ 8 cm accounted for 93.8% (45/48) of the group.

All patients were diagnosed pathologically as neuroendocrine tumors by biopsy, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2000 diagnostic criteria for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors[8]. The pathological types included 43 cases of typical carcinoid tumors and 5 cases of atypical carcinoids/poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma/small cell carcinomas.

The median diameter of the tumors was 0.8 ± 1.413 cm. In 27 patients, the diameters were 0.1 to 0.9 cm; in 15, they were 1.0 to 1.9 cm; and in 6, they were ≥ 2 cm. Immunohistochemical staining showed that the tumors were positive for chromogranin A (CgA), synaptophysin (Syn), and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) in 57.6% (19/33), 100% (32/32), and 95.2% (20/21) of cases, respectively. Among the 48 cases, 87.5% (42/48) had a CT scan to determine whether or not there were metastases to the lymph nodes or distant organs, and 41.7% (20/48) underwent ultrasonic endoscopy to confirm the depth of invasion into the rectal wall. The distant metastasis rate was 4.2% (2/48) at the time of diagnosis. All patients were staged according to the TNM staging system for rectal neuroendocrine tumors (Tables 1 and 2)[7]. Stages I, II, III and IV tumors accounted for 83.3% (40/48), 4.2% (2/48), 8.3% (4/48), and 4.2% (2/48) of patients, respectively. Surgical treatment was undertaken in 97.9% (47/48) of patients, including transanal extended excision in 72.9% (35/48), Dixon’s operation for rectal cancer in 16.7% (8/48), Mile’s surgery for rectal cancer in 4.2% (2/48), and endoscopic resection in 4.2% (2/48). One patient did not received locoregional therapy because he was initially diagnosed as stage IV disease with liver metastasis.

| TNM classification | |

| T: Primary tumor | |

| Tx | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 | Tumor invades the mucosa or submucosa and size ≤ 1 cm |

| T1a: size < 1 cm | |

| T1b: size 1-2 cm | |

| T2 | Tumor invades the muscularis propria or size > 2 cm |

| T3 | Tumor invades subserosa/pericolic/perirectal fat |

| T4 | Tumor directly invades other organs/structures and/or perforates the visceral peritoneum |

| N: Regional lymph nodes | |

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M: Distant metastasis | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| Disease stage | T: Primary tumor | N: Regional nodes | M: Distant metastasis |

| Stage IA | T1a | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IB | T1b | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIA | T2 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIB | T3 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIIA | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| Stage IIIB | Any T | N1 | M0 |

| Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Among the 27 patients with tumors less than 1 cm in diameter, 81.5% (22/27) received transanal extended excision, 7.4% (2/27) received endoscopic resection, and 11.1% (3/27) received Dixon’s operation. Among the 15 patients with tumors that were between 1 cm and 2 cm in diameter, the corresponding percentages were 80% (12/15), 20% (3/15), and 0%, respectively. Among the 5 patients with tumors larger than 2 cm in diameter, 20% (1/5) received transanal extended excision, 40% (2/5) received Dixon’s surgery, and 40% (2/5) received Mile’s surgery.

The median survival time in the patients studied was not reached. The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 100%, 93.7% and 91.3%, respectively. Three patients demonstrated recurrence and metastases after radical resection, and the mean time for recurrence/metastasis was 14 mo. Log-rank analysis of prognostic factors showed that there was a statistically significant difference in the 5-year survival rate between patients ≥ 55 years of age and patients < 55 years of age (P = 0.032). Subgroup analysis stratified by TNM stage and tumor type showed that the 5-year survival rate in patients aged ≥ 55 years was lower in those with atypical rectal neuroendocrine tumors or disease at TNM stage III/IV (Table 3).

| ≥ 55 yr of age | < 55 yr of age | P value | |||

| n | Survival rate | n | Survival rate | ||

| Tumor type | |||||

| Typical | 20 | 95% | 23 | 100% | 0.284 |

| Atypical | 3 | 0% | 2 | 100% | 0.063 |

| TNM stage | |||||

| I/II | 19 | 94.70% | 23 | 100% | 0.271 |

| III/IV | 4 | 25.00% | 2 | 100% | 0.144 |

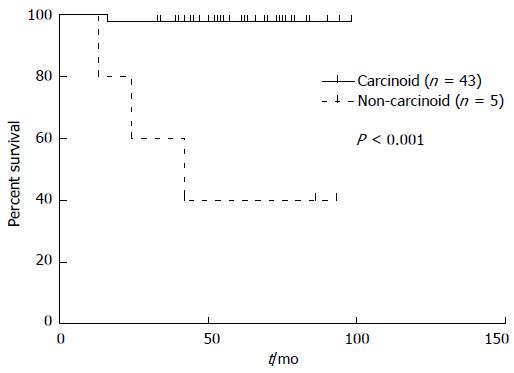

In terms of tumor diameters, the patients were classified into 3 subgroups: those with tumor diameters < 1.0 cm, between 1.0 and 2.0 cm, and > 2.0 cm. There was a statistically significant difference in the overall survival between these subgroups (P < 0.001), and also between the pathological types of carcinoid and non-carcinoid (atypical carcinoid and neuroendocrine carcinoma/small cell carcinoma) tumors (P < 0.001) (Figure 1), the TNM stages (P < 0.001), and the surgical approaches employed (P = 0.002). However, when these factors were introduced into the Cox proportional hazards model for the multivariate analysis, only the pathological type was an independent prognostic factor (HR = 2.797, 95%CI: 1.676-4.668, P = 0.004).

Rectal carcinoid tumors account for 1% to 2% of all rectal tumors, and occur mostly in the 60-70 years old age group[9]. Data on 1481 cases of rectal neuroendocrine tumors occurring over a period of 30 years in the United States showed that males accounted for 51.7% of the overall incidence[1]. In the present study, the most common age of onset was 40-59 years (median of 54 years), with males accounting for 61.4% of the overall incidence. This can be compared with other western data, which shows a trend towards a younger age of onset and a higher incidence in males.

Nearly 50% of our patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors showed no obvious symptoms at the time the diagnosis was confirmed. Rather, the tumors were generally found by conventional colonoscopy. In patients with symptoms, rectal bleeding, pain, and constipation were noted most commonly. Very few patients had carcinoid syndromes, which may be due to the fact that rectal carcinoid tumors rarely secrete 5-hydroxytryptamine[10]. Rectal carcinoid tumors can arise in the entire rectum. In this study, the median distance between the tumors and the anal edges was 5.0 cm, and patients with a distance of ≤ 8 cm between the tumor and the anal edge accounted for 94.1% of all cases, indicating that the tumors mostly arise in the middle and lower rectum.

CgA, Syn and NSE are commonly used as biomarkers to detect neuroendocrine tumors. In the group of patients we studied, positive immunohistochemical staining rates for these markers were 57.6%, 100% and 95.2%, respectively. This indicates that Syn and NSE staining are more sensitive for the diagnosis of rectal neuroendocrine tumors than CgA. It has been reported in the literature that the most common sites of metastases of rectal neuroendocrine tumors are lymph nodes and the liver, and only rarely the lungs[10]. In the present study, 5 patients were found to have distant metastases at their first visit, and 4 developed postoperative distant metastases. The most common sites of metastases were, successively, the liver and lymph nodes. The lymph node metastases involved nodes adjacent to the iliac arteriovenous, retroperitoneal and inguinal lymph nodes. When rectal neuroendocrine tumors have an associated malignancy, their incidence was about 7%-9%[11]. In the patient group we studied, 5 (8.8%) patients had concomitant colorectal adenocarcinomas.

In 2003, Modlin et al[1] reported that the overall 5-year survival rate of patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors was 69.5% to 87.4%. In comparison, the overall 5-year survival rate in the patients we studied was higher (88.6%). The TNM stage is an important prognostic factor[12-15]. Our study mainly included patients with stage I tumors, reflecting the relatively indolent biological behavior of rectal neuroendocrine tumors which are characterized by shallow local invasion and few lymph node and distant metastases. In a statistical analysis, Landry et al[12] observed that patients with stage I tumors accounted for 83% of all patients. In the present study, the 5-year survival rate of patients with stage I tumors reached 97.6%, and the 5-year survival rates of patients with stages II, III and IV tumors were 100%, 75% and 0%, respectively. Univariate analysis showed that TNM staging was a prognostic factor (P < 0.001).

The pathological type of tumor also significantly affects the prognosis[16-18]. According to the WHO 2000 pathological diagnostic criteria for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors based on tissue structures, the degree of differentiation, mitotic rate, and the presence or absence of necrosis, they can be subclassified into three types: typical carcinoid tumors, atypical carcinoid tumors, and neuroendocrine (small cell/large cell) carcinomas. The typical carcinoids, which accounted for a large proportion of the rectal neuroendocrine tumors (85.2%) in this study, have a good prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate approaching 97.8%. The atypical carcinoids and neuroendocrine carcinomas account for a smaller proportion of tumors, and they demonstrate a significantly worse prognosis. The 5-year survival rate for this subgroup was only 33.3% in the present study. Only 4 patients were diagnosed as having a stage IV neuroendocrine carcinoma at the first patient visit, indicating that this pathological type is highly invasive. In the multivariate analysis that we conducted, the pathological type proved to be an independent prognostic factor (P = 0.004).

Other studies have suggested that the diameters of rectal neuroendocrine tumors are closely associated with the invasion depth and with lymph node and distant metastases, and that they have definite prognostic meaning[18-21]. Patients with tumor diameters between 0.1 and 1 cm have been reported to have a distant metastasis rate of less than 5% and a 5-year survival rate of 81%. In contrast, most patients with tumor diameters ≥ 2 cm had distant metastases and their 5-year survival rate was 18% to 40%[5,9]. In our study, the univariate analysis of prognostic factors showed that tumor diameter was significantly associated with the prognosis (P = 0.001). For patients with lesions 0.1-1 cm, 1.1-1.9 cm and ≥ 2 cm in diameter, the 5-year survival rates were 100%, 93.3%, and 40%, respectively. In those with tumors ≥ 2 cm with muscular or serosal invasion, the 5-year survival rate was 50% (3/6), and in those with distant metastasis, the 5-year survival rate was also 50% (3/6). In 5 of the 6 patients with lesions ≥ 2 cm who had lymph node or distant metastases, the 5-year survival rate was 40%.

The surgical approach was also a prognostic factor in our study. Local excision approaches included transanal extended excisions and endoscopic excisions, the surgical indications for which were tumor diameters ≤ 1 cm without muscular layer invasion and without lymph node or distant metastasis[22-25]. Twenty-four of 27 patients (88.9%) who had tumor diameters < 1 cm underwent local excisions and the 5-year survival rate in these patients was 100%. Laparotomy procedures included Mile’s surgery and Dixon’s operation, the indications for which were advanced disease with tumor diameters ≥ 2 cm, muscular layer invasion, and lymph node and distant metastases[26]. In this group, the prognosis was poor, and the 5-year survival rate was 70.1%. There is still much debate concerning the surgical approaches for patients with tumor diameters between 1 and 2 cm. Naunheim et al[18] reported that after local excision, 5% of patients with tumor diameters < 2 cm still had distant metastases, while Jetmore et al[27] reported that the local recurrence rate was 0% in patients with tumor diameters < 2 cm and the curative effects were satisfactory following local excision. Among the patients in our study with tumor diameters between 1 and 2 cm, 12 chose to undergo local excisions and their 5-year survival rate was 100%. Three patients chose to undergo laparotomies and the 5-year survival rate in this group was only 66.7%, suggesting that more radical surgery does not prolong the survival time.

In 2008, Landry et al[12] reported that age ≥ 65 years was a poor prognostic factor for rectal neuroendocrine tumors. In our study, the median age of the patients was 54 years, and the survival analysis showed that the prognosis in those over 55 years of age at diagnosis declined. A stratified analysis showed that while the 5-year survival rate of patients under the age of 55 years was 100%, in patients between 60 and 70 years of age it was 64.3% and in those between 70 and 80 years of age it was 66.7%. Possible reasons for this might be that patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors who do not have distant metastases have a better prognosis, and most are able to survive long-term. However, elderly patients with underlying diseases usually have decreased organ function and insufficient immune function, and these patients often die due to their underlying disease rather than tumor-specific factors.

It is worth noting that although patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors have a good prognosis, 7% to 10% still have liver metastases or distant lymph node metastases. This study showed that the 3-year survival rate of patients with stage IV tumors was 0%. Other studies undertaken in western countries have shown that the 5-year survival rate of patients with stage IV tumors ranges from 20.6% to 32.3%[1], reflecting the high malignancy rate of these tumors. There is no significant progress in the treatment of such patients, and this is an area that urgently requires further investigation.

Rectal neuroendocrine tumors are rare but have exhibited a slow upward trend in their incidence since the 1990s. There are significant differences in the prognosis of individuals with these tumors.

In 2003, a population-based study reported that the 5-year survival rate of patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors was 88.3%. However, in recent years, studies have found that typically malignant biological behavior, such as lymph node and distant metastases, have appeared in patients with these tumors. For example, it has been reported that the 3-year survival rate in a group of patients with colorectal neuroendocrine tumors was only 13%. This indicates that further studies are needed to determine factors that have significant prognostic value.

In this study, the characteristics and outcomes of rectal neuroendocrine tumors were analyzed in a cohort of 48 patients. Several prognostic factors were identified, among which the carcinoid pathologic type had the most significant impact on overall survival.

This is a good study in which authors analyze the clinicopathologic characteristics and prognostic factors of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. The results are interesting and suggest that the pathological type of the tumor is an independent prognostic factor.

P- Reviewer: Kim YJ, Tepes B S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Scherübl H, Streller B, Stabenow R, Herbst H, Höpfner M, Schwertner C, Steinberg J, Eick J, Ring W, Tiwari K. Clinically detected gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are on the rise: epidemiological changes in Germany. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9012-9019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fraenkel M, Kim M, Faggiano A, de Herder WW, Valk GD. Incidence of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review of the literature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:R153-R163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Aytac E, Ozdemir Y, Ozuner G. Long term outcomes of neuroendocrine carcinomas (high-grade neuroendocrine tumors) of the colon, rectum, and anal canal. J Visc Surg. 2014;151:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bernick PE, Klimstra DS, Shia J, Minsky B, Saltz L, Shi W, Thaler H, Guillem J, Paty P, Cohen AM. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:163-169. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Heo J, Jeon SW, Jung MK, Kim SK, Shin GY, Park SM, Ahn SY, Yoon WK, Kim M, Kwon YH. A tailored approach for endoscopic treatment of small rectal neuroendocrine tumor. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2931-2938. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Rindi G, Klöppel G, Couvelard A, Komminoth P, Körner M, Lopes JM, McNicol AM, Nilsson O, Perren A, Scarpa A. TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:757-762. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Solcia E, Sobin LH, Arnold R. Endocrine tumors of the colon and rectum. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Lyon: IARC Press 2000; 137-139. |

| 9. | Modlin IM, Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997;79:813-829. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kulke MH, Mayer RJ. Carcinoid tumors. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:858-868. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Landry CS, Brock G, Scoggins CR, McMasters KM, Martin RC. A proposed staging system for rectal carcinoid tumors based on an analysis of 4701 patients. Surgery. 2008;144:460-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Weinstock B, Ward SC, Harpaz N, Warner RR, Itzkowitz S, Kim MK. Clinical and prognostic features of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;98:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim MS, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Lee KY, Kim NK. Clinical outcomes for rectal carcinoid tumors according to a new (AJCC 7th edition) TNM staging system: a single institutional analysis of 122 patients. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:835-841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chagpar R, Chiang YJ, Xing Y, Cormier JN, Feig BW, Rashid A, Chang GJ, You YN. Neuroendocrine tumors of the colon and rectum: prognostic relevance and comparative performance of current staging systems. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1170-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jernman J, Välimäki MJ, Louhimo J, Haglund C, Arola J. The novel WHO 2010 classification for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours correlates well with the metastatic potential of rectal neuroendocrine tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vilor M, Tsutsumi Y, Osamura RY, Tokunaga N, Soeda J, Ohta M, Nakazaki H, Shibayama Y, Ueno F. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the rectum. Pathol Int. 1995;45:605-609. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Naunheim KS, Zeitels J, Kaplan EL, Sugimoto J, Shen KL, Lee CH, Straus FH. Rectal carcinoid tumors--treatment and prognosis. Surgery. 1983;94:670-676. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Gleeson FC, Levy MJ, Dozois EJ, Larson DW, Wong Kee Song LM, Boardman LA. Endoscopically identified well-differentiated rectal carcinoid tumors: impact of tumor size on the natural history and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:144-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim DH, Lee JH, Cha YJ, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim H, Kim WH, Hong SP. Surveillance strategy for rectal neuroendocrine tumors according to recurrence risk stratification. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:850-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim GU, Kim KJ, Hong SM, Yu ES, Yang DH, Jung KW, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK. Clinical outcomes of rectal neuroendocrine tumors ≤ 10 mm following endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 2013;45:1018-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jeon JH, Cheung DY, Lee SJ, Kim HJ, Kim HK, Cho HJ, Lee IK, Kim JI, Park SH, Kim JK. Endoscopic resection yields reliable outcomes for small rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:556-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhou FR, Huang LY, Wu CR. Endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal carcinoids under micro-probe ultrasound guidance. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2555-2559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Akahoshi K, Motomura Y, Kubokawa M, Matsui N, Oda M, Okamoto R, Endo S, Higuchi N, Kashiwabara Y, Oya M. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a rectal carcinoid tumor using grasping type scissors forceps. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2162-2165. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Abe T, Kakemura T, Fujinuma S, Maetani I. Successful outcomes of EMR-L with 3D-EUS for rectal carcinoids compared with historical controls. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4054-4058. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kasuga A, Chino A, Uragami N, Kishihara T, Igarashi M, Fujita R, Yamamoto N, Ueno M, Oya M, Muto T. Treatment strategy for rectal carcinoids: a clinicopathological analysis of 229 cases at a single cancer institution. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1801-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jetmore AB, Ray JE, Gathright JB, McMullen KM, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE. Rectal carcinoids: the most frequent carcinoid tumor. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:717-725. [PubMed] |