INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C is a major public health problem affecting approximately 2% of the world’s population, which constitutes almost 170 million people[1]. Most of the infections are due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1, which responded poorly to therapy until the advent of direct-acting agents[2]. With such a large disease burden, HCV is currently the most common cause of hepatocellular cancer and liver transplantation in the United States and Europe[3].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

HCV is a positive single-stranded RNA virus that exists in 6 different genotypes, with genotype 1 being the most common. Virus replication occurs through an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase lacking the proofreading function, thereby producing many quasispecies in an infected person. This virus production is likely one of the primary causes for the limited immune-mediated control over HCV[1]. Spontaneous recovery from chronic infection (beyond 6 mo after acute infection) is rare and cHCV infection can lead to the development of liver cirrhosis, and liver failure and/or hepatocellular carcinoma in a substantial number of patients.

INFLAMMATORY MILIEU IN CHRONIC HCV (cHCV) INFECTION

cHCV infection is a state of persistent inflammation in the liver, although the exact mechanism for its pathogenesis remains unclear. Patients with cHCV have altered monocyte functions and are known to produce higher levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)[4]. When acute infection/inflammation becomes chronic, the mechanisms that dampen the inflammation are impaired[5,6]. This impairment leads to end-organ damage over time. A similar process occurs when acute HCV infection becomes chronic, leading to liver damage/fibrosis and, eventually, cirrhosis of the liver[6].

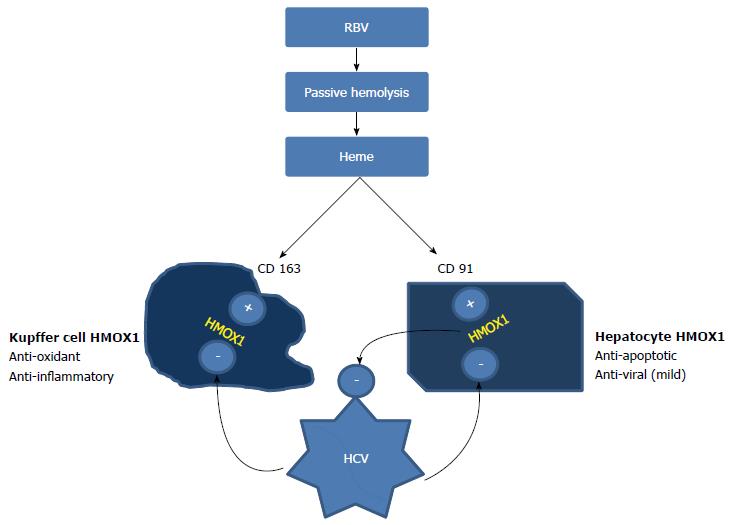

Kupffer cells (KCs) are resident macrophages in the liver that appear to originate from bone marrow. Chronic non-specific activation of these cells occurs in cHCV, leading to heightened production of IFN-γ, TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines. CD163 receptors on the liver cells also have concomitantly increased expression, which appears to be an effort to suppress/resolve the inflammation[7]. CD163 is a hemoglobin scavenger receptor, which, under normal circumstances, promotes anti-inflammatory response by upregulating heme metabolized and detoxified by heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1). However, patients with cHCV have reduced levels of HMOX1, even with high levels of CD163[8]. These seemingly opposing actions help to perpetuate viremia and chronic inflammation in the liver, along with a state of immune tolerance to HCV that decreases the effectiveness of exogenous IFN in clearing the virus[9] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Opposing actions of ribavirin and HCV on cellular HMOX1 concentration.

Ribavirin releases heme from erythrocytes through passive hemolysis. The uptake of heme by hepatocytes (via CD91) and Kupffer cells (via CD163) activates heme oxygenase. HMOX1 acts as a powerful anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant in Kupffer cells, whereas it has anti-apoptotic and weak antiviral properties when expressed in hepatocytes. HCV core protein inhibits HMOX1 in both of these cells, producing contrasting actions. This inhibition perpetuates viremia and results in immune tolerance, decreasing the efficiency of IFN in clearing HCV. Heme may be able to reverse the blocking effect of Hepatitis C on HMOX1. CD91: Receptor for the heme-hemopexin complex on hepatocytes. This receptor mediates heme uptake, HMOX1 activation. HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HMOX1: Heme Oxygenase - 1; RBV: Ribavirin; IFN: Interferon.

CURRENT CHCV TREATMENT OPTIONS

Since the early 1990s, IFN-α has been the mainstay of treatment for cHCV. Introducing ribavirin (RBV) to the anti-HCV therapy greatly improved the sustained virological response (SVR) or cure rates. Major trials have concluded that RBV addition to IFN therapy improves SVR to 40%-50% in patients with genotype 1, which is far superior to therapy with pegylated IFN alone (15%-20%)[10]. The following disparate hypotheses have been proposed to explain the synergy of ribavirin with IFN in increasing the SVR: (1) direct inhibition of HCV replication; (2) inhibition of host inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase; (3) mutagenesis induction in rapidly replicating virus, inducing error catastrophe; (4) immunomodulation by inducing the Th1 response; and (5) modulation of Th1 (cell mediated immunity) and Th2 (humoral immunity) lymphocyte balance[11]. None of these hypotheses has convincingly explained the synergistic antiviral effects of the combined therapy with IFN and RBV on hepatitis C.

RBV alone does not have any appreciable direct anti-HCV effects, and the exact mechanism of action in cHCV therapy remains a mystery. Although various new direct-acting antiviral agents with far superior SVR compared with the present treatment options are being developed and approved for the treatment of cHCV, RBV remains an integral part of several of the new antiviral regimens. Thus, deciphering the mechanism of RBV in cHCV therapy is important for continuing further research in this field for therapeutic purposes and for learning more concerning the pathogenesis of liver disease in cHCV infection.

Use of IFN-α in cHCV

Treatment with IFN-α induces the expression of specific genes in liver cells known as IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs)[12]. These genes serve as mediators for exerting the antiviral response of IFN. Patients with low baseline levels of ISGs tend to show good response to exogenous IFN[9]. However, high pre-treatment endogenous IFN and ISG production by KCs and peripheral blood mononuclear cells has been associated with reduced SVR rates with combination therapy[13]. A recent study concluded that if this chronic local production of IFN by Kupffer cells is disrupted, then a break in tolerance and improved outcomes may occur in cHCV patients receiving combined IFN-α/RBV therapy[9].

Use of RBV in cHCV

The use of RBV as a combination therapy with IFN for chronic HCV patients was first proposed in the early 1990s. Various studies conducted to evaluate the role of RBV in cHCV infection have shown that it has minimal effects on viremia; however, RBV monotherapy decreases inflammation in these patients, as evidenced on serial liver biopsies and by reduced transaminase levels[14,15]. However, the biochemical response to RBV appears to accurately predict the response to subsequent combination therapy with IFN-α, as shown by Rotman et al[16] This finding suggests that the anti-inflammatory activity of ribavirin plays a critical role in its synergy with IFN against HCV. As mentioned earlier, several different mechanisms have unsuccessfully been explored to explain this synergy.

Combination therapy: RBV and IFN

Combination therapy with RBV and IFN leads to decreased inflammation, as measured by the reduction in the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and transaminases in patients who respond to the treatment (responders) compared with those patients who do not respond to the treatment[17,18]. Inhibiting this inflammation before or during IFN therapy may improve outcomes, as concluded by Lau et al[9] after studying the effect of combination therapy on rapid responders and non-responders. We propose that this is precisely the role played by ribavirin alone or in combination with exogenous IFN in cHCV patients.

HEMOLYTIC ANEMIA IN RBV THERAPY

Therapy with RBV results in hemolytic anemia due to the accumulation of the drug in the red blood cells (RBCs), frequently leading to adjustment of the dosage and/or discontinuation of therapy, which, in turn, can affect the SVR. Ribavirin-induced hemolysis is passive and non-inflammatory-/non-immune-mediated. Ribavirin-induced hemolysis is also dose-related and sustained, unlike hemolysis in G-6-PD deficiency situations. The reduction in hemoglobin levels appears to correlate directly with the degree of hemolysis and inversely with the erythropoetic ability of the bone marrow. Hemolysis and reduced hemoglobin can lead to major side effects; however, treatment-related anemia, particularly during the first 4-8 wk, correlates well with the efficacy (SVR rate) of the combination therapy[19].

HMOX1: A MIRACULOUS ANTI-INFLAMMATORY ENZYME

HMOX1 is one of the most potent intracellular anti-inflammatory mediators in humans. HMOX1 was first characterized by Tenhunen et al[20] in 1968 as an enzyme responsible for the breakdown and detoxification of heme in humans. HMOX1 is the rate-limiting enzyme that catabolizes heme to produce equimolar concentrations of biliverdin, carbon monoxide and iron. Heme Oxygenase is present in three isoforms: HMOX1, HMOX2, and HMOX3, respectively[21]. HMOX2 and HMOX3 are constitutively expressed, whereas HMOX1 is the primary inducible form responsible for heme catabolism. HMOX1 can be induced by its substrate heme and by numerous oxidative stress stimuli including, but not limited to, UV light, lipopolysaccharide, heat shock or hyperoxia. Since the discovery of this property, multiple researchers have shown its benefit as an anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and anti-proliferative agent[22,23]. Experiments in knockout mice (HMOX1-/-) demonstrated significantly higher cytokine responses, including TNF-α and IFN-γ in comparison to wild type (HMOX1+/+) when exposed to mitogens, such as lipopolysaccharide[24]. These actions of HMOX1 have proven to be protective against inflammatory insults to the brain, liver, kidney and lung.

As mentioned previously, chronic hepatitis C is a state of chronic and persistent inflammation of the liver. The HCV genome consists of genes encoding 10 proteins, which include core, envelope, and non-structural proteins[25]. Of these proteins, core protein and NS5A are the strongest regulators of oxidative stress in HCV. In 2002, Okuda et al[26] and Li et al[27] demonstrated that core protein is capable of inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) both in vivo and in vitro in hepatitis C. These ROS activate different proteins, including Nrf2, which controls the ability of cells to address oxidative stress[28]. Similarly, non-structural protein NS5A causes Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum, which triggers ROS release in the mitochondria, leading to the activation of nuclear factor kappa B and signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 pathways[29]. These pathways are implicated in tumor development, growth and metastasis[30,31]. ROS ultimately lead to oxidation of membrane lipids and cell death. With this knowledge, anti-oxidants have been proposed to be utilized in HCV infections, where these molecules can lead to impaired HCV replication and/or increase the effectiveness of IFN therapy. A phase I clinical trial by Melhem et al[32] showed normalized liver enzymes (44% of patients), decreased viral load (25%) and histological improvement (36.1%) in patients with cHCV who were treated with a combination of anti-oxidant therapy.

HMOX1 in HCV

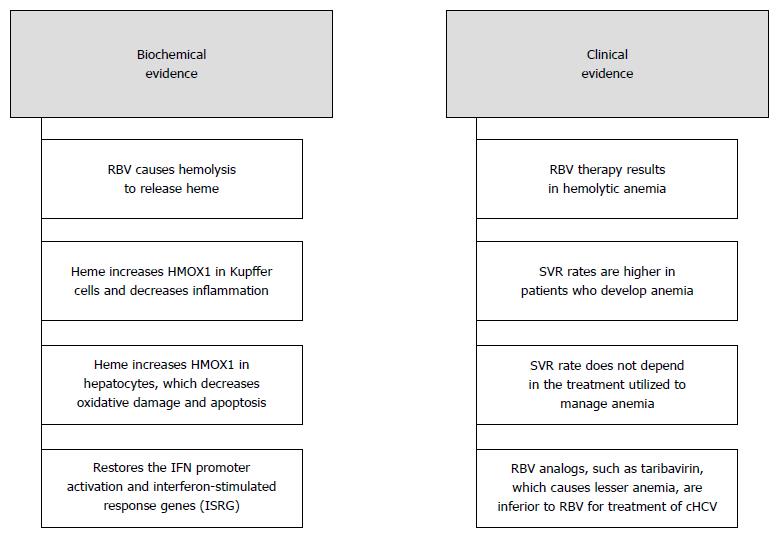

During the last decade, the discovery of the anti-inflammatory properties of HMOX1 and the presence of oxidative stress in patients with cHCV has caused many researchers to evaluate the use of HMOX1 as a therapeutic option in cHCV. Down-regulation of HMOX1 is observed in hepatocyte cell lines that express HCV core protein, and HMOX1 induction in these cells in response to cytotoxic stressors is also diminished[33]. Heme is a potent inducer of HMOX1 and can abrogate HCV-induced HMOX1 suppression in hepatocytes. Ribavirin-induced hemolysis provides sufficient heme that (1) increases HMOX1 in Kupffer cells and decreases inflammation; (2) increases HMOX1 in hepatocytes, which decreases the oxidative damage and apoptosis caused by HCV and which slightly decreases HCV replication; and (3) restores IFN promoter activation and ISG production, which are altered by HCV core proteins and by NS3/4A, which interfere with IFN signaling[34].

BIOCHEMICAL EVIDENCE FOR HEMOLYSIS AS THE MECHANISM FOR THE SYNERGISTIC ACTION OF RIBAVIRIN AGAINST HCV

Zhu et al[35] evaluated the effect of HMOX1 overexpression and induction on human hepatoma cell lines. HMOX1 overexpression in these cell lines led to a marked reduction in the HCV RNA titer by an average of 3.8-fold in comparison to the controls, and these effects were reversed with HMOX1 knockdown. HCV RNA replication was reduced with the induction of HMOX1 by hemin. The same study also showed that HMOX1-overexpressing subclones showed reduced pro-oxidant levels and had improved viability to oxidant-mediated cytotoxicity. In 2007, Shan et al[36] showed that increasing HMOX1 by silencing the Bach 1 gene using an antagonist of microRNA-122 (miR-122) decreases HCV replication by 64%-84%, depending on the cell line (The Bach 1 gene represses HMOX1, and miR-122 is required for HCV RNA replication.). A similar study by Hou et al[37] demonstrated that microRNA-196 can be used to suppress the Bach 1 gene, leading to HMOX1 upregulation, which inhibited HCV expression. In an experimental model, lucidone, which is a plant compound, was shown to enhance Nrf2 expression, leading to HMOX1 activation and HCV RNA suppression through increasing the antiviral IFN response and through blocking HCV NS3/4A protease[38]. This compound acted synergistically with IFN, protease inhibitor telaprevir, NS5A inhibitor or NS5B inhibitor to suppress HCV RNA replication, and its effects were nullified by blocking HMOX1 gene expression.

HMOX1 catabolizes heme to produce equimolar concentrations of carbon monoxide, biliverdin and iron (which induces and binds to ferritin). Biliverdin, carbon monoxide and ferritin have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties. Among the three, biliverdin has been studied the most in hepatitis C. Zhu et al[39] highlighted the role of biliverdin as the primary antiviral agent released by heme catabolism. Biliverdin possesses significant antiviral activity and inhibits NS3/4A protease, which is utilized by HCV. Biliverdin also enhances the action of IFN when used together against HCV-infested cells.

CLINICAL EVIDENCE FOR HEMOLYSIS AS THE MECHANISM FOR THE SYNERGISTIC ACTION OF RIBAVIRIN AGAINST HCV INFECTION

The following clinical outcomes have been seen in patients undergoing treatment with anti-HCV therapy (Figure 2): (1) Sulkowski et al[40] evaluated the role of anemia in cHCV patients receiving combination therapy. Among patients treated with boceprevir, RBV and Peg-IFN combination therapy, those patients who developed anemia had a much higher SVR rate (72%) than those patients who did not develop anemia (58%). Another study showed that a higher dose of RBV is associated with a higher degree of anemia and an improved SVR rate[41]; (2) once anemia develops during RBV therapy, SVR rates do not depend on the approach used to manage anemia (reduced RBV or use of erythropoietin)[40]. Those patients who were given erythropoietin-stimulating agents were able to receive higher daily and cumulative doses of ribavirin. This finding suggests that the level of ribavirin in the serum or RBCs does not influence SVR but that the degree of anemia, which is a surrogate marker for hemolysis in those patients with healthy bone marrow, does; (3) cHCV patients with thalassemia, which precludes a robust bone marrow response to RBV-induced hemolysis, respond poorly to combination therapy. This poor response can be slightly mitigated by periodic packed RBC transfusions along with iron chelation. However, interestingly, IFN alone appeared to result in high SVR rates of 60%-70% in younger (< 18 years) cHCV patients with thalassemia, with no additional benefit from ribavirin. This finding suggests that hemolysis may be a more important factor than the serum or RBC level of ribavirin in achieving SVR[42]; (4) ribavirin analogs, such as taribavirin, which increases the intracellular ribavirin levels in the hepatocytes, and levovirin, which causes lesser hemolysis and anemia compared with ribavirin, produced inferior SVR rates when combined with IFN-α[43,44]. A safer dosage of taribavirin which produces a significant lesser degree of anemia compared with RBV was found to be inferior to RBV in treating cHCV infection[43]; and (5) inosine triphosphatase gene polymorphisms, which decrease hemolysis, appear to reduce clinically significant anemia and the required dose of ribavirin[45]. However, the increased daily and cumulative dosing of ribavirin does not translate into improved SVR. This finding again suggests that the ribavirin level is less important for SVR than the dose sufficient to cause adequate hemolysis.

Figure 2 Summary of the bio-chemical and clinical evidence of our proposed hypothesis.

Ribavirin leads to passive hemolysis to release heme which activates HMOX1 in the liver and produces a synergistic effect with IFN on cHCV infection. HMOX1: Heme Oxygenase - 1; IFN: Interferon.

CONCLUSION

One of the possible mechanisms of ribavirin’s synergy with IFN in cHCV therapy is due to passive hemolysis, which supplies heme to the hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. Heme induces HMOX1 and increases the products of heme metabolism, which reverses the pro-oxidant, pro-inflammatory, immune tolerant state induced by HCV. The break in tolerance produced by HMOX1 and its products allow for optimal induction of ISGs by exogenously administered IFN, resulting in increased SVR.

Most likely by the same mechanism, ribavirin can also synergize with direct-acting agents against HCV by improving the intracellular antioxidant and antiviral actions in the liver and by improving the efficacy of endogenous IFN. This hypothesis is testable and may lead to newer and safer medications that can overcome the anti HMOX1 effect of HCV by mechanisms other than hemolysis induction.

P- Reviewer: Aghakhani A, Baran B, Gelderblom HC, Hou WH, Zhang SJ S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM