Published online Nov 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15787

Revised: May 21, 2014

Accepted: June 13, 2014

Published online: November 14, 2014

Processing time: 229 Days and 15.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the effect of vitamin D (VD) concentrations and VD supplementation on health related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients.

METHODS: A cohort of 220 IBD patients including 141 Crohn’s disease (CD) and 79 ulcerative colitis (UC) patients was followed-up at a tertiary IBD center. A subgroup of the cohort (n = 26) took VD supplements for > 3 mo. Health related quality of life was assessed using the short IBD questionnaire (sIBDQ). VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score were assessed between August and October 2012 (summer/autumn period) and between February and April 2013 (winter/spring period). The mean VD serum concentration and its correlation with disease activity of CD were determined for each season separately. In a subgroup of patients, the effects of VD supplementation on winter VD serum concentration, change in VD serum concentration from summer to winter, and winter sIBDQ score were analyzed.

RESULTS: During the summer/autumn and the winter/spring period, 28% and 42% of IBD patients were VD-deficient (< 20 ng/mL), respectively. In the winter/spring period, there was a significant correlation between sIBDQ score and VD serum concentration in UC patients (r = 0.35, P = 0.02), with a trend towards significance in CD patients (r = 0.17, P = 0.06). In the winter/spring period, VD-insufficient patients (< 30 ng/mL) had a significantly lower mean sIBDQ score than VD-sufficient patients; this was true of both UC (48.3 ± 2.3 vs 56.7 ± 3.4, P = 0.04) and CD (55.7 ± 1.25 vs 60.8 ± 2.14, P = 0.04) patients. In all analyzed scenarios (UC/CD, the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period), health related quality of life was the highest in patients with VD serum concentrations of 50-59 ng/mL. Supplementation with a median of 800 IU/d VD day did not influence VD serum concentration or the sIBDQ score.

CONCLUSION: VD serum concentration correlated with health related quality of life in UC and CD patients during the winter/spring period.

Core tip: In a cohort of 220 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, we observed that vitamin D (VD)-insufficient patients (< 30 ng/mL) had a lower health related quality of life (sIBDQ) in the winter/spring period. In all analyzed scenarios (ulcerative colitis/Crohn’s disease, the summer/autumn and the winter/spring period), the health related quality of life was the highest in patients with VD serum concentrations of 50-59 ng/mL, indicating a possible target level for therapeutic VD supplementation. Furthermore, we observed that supplementation with currently recommended doses of VD supplementation of 800 IU/d VD did not influence VD serum concentration or the sIBDQ score.

- Citation: Hlavaty T, Krajcovicova A, Koller T, Toth J, Nevidanska M, Huorka M, Payer J. Higher vitamin D serum concentration increases health related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(42): 15787-15796

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i42/15787.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15787

The well known north-south gradient of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) prevalence, epidemiological data, data from animal models, and genetic association studies of vitamin D (VD) receptor polymorphisms suggest that VD plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD[1-3]. There is increasing evidence of the influence of VD on disease activity and its possible therapeutic use.

The role of VD in calcium metabolism and healthy bone development has been recognized for more than a century. However, the discovery that the VD receptor is present in most tissues and cells of the body provided new insight into the non-calcemic functions of VD, such as cell proliferation, immunomodulation and cell differentiation[4,5]. The VD receptor is abundantly expressed in immune cells. VD stimulates the production of T-regulatory lymphocytes and expression of interleukin 4 and transforming growth factor β, inhibits the differentiation of CD4+ T lymphocytes into Th1 cells, and suppresses the effector functions of T lymphocytes[4]. VD deficiency is suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of various immune-mediated diseases, including IBD, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, type I diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus and psoriasis[6]. VD receptor agonists have favorable effects in animal models of these diseases[7].

Modern lifestyles appear to result in widespread VD deficiency, especially at the end of winter[8,9]. In a large population study from Germany, 81% of men and 89% of women had a VD intake from food of lower than 200 IU/d and 57% of men and 58% of women were VD-deficient (< 20 ng/mL)[9].

VD deficiency is common among IBD patients, including those who have been recently diagnosed with such diseases[10-12]. The positive effects of VD are well documented in many animal models of IBD[7]. Limited clinical data suggest that there is an association between low VD concentration and increased disease activity in ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD)[13,14].

There are limited clinical data on the effect of VD replacement therapy on disease activity or health related quality of life. Miheller et a[15] observed that the CD activity index (CDAI) score and the concentration of C-reactive protein were significantly reduced in a small cohort of 35 CD patients in remission who received 1000 IU VD supplementation per day. In a small placebo-controlled randomized trial of CD patients, oral supplementation with 1200 IU VD3/day reduced the risk of relapse from 29% to 13% (P = 0.06)[16]. However, in another small prospective study, VD replacement therapy did not influence disease activity in IBD patients[17].

Given the controversy concerning the effects of VD in IBD patients, the primary aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of VD serum concentration on health related quality of life in CD and UC patients. In addition, we also assessed the impact of supplementation with currently recommended doses of VD on the serum concentration of VD and health related quality of life.

This was a retrospective study of a cohort of IBD patients that were followed-up at a tertiary IBD center between August 1, 2012 and April 30, 2013.

Patients with CD and UC who were older than 18 years and managed by the IBD center of the Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospital Bratislava, Slovak Republic, who visited our center between August 1, 2012 and October 30, 2012 (summer/autumn period) and between February 1, 2013 and April 30, 2013 (winter/spring period) were screened. These periods were selected to match the expected highest vitamin D levels at the end of a high sunshine period and the lowest vitamin D levels at the end of a low sunshine period in our geographical area. Patients were eligible if their VD status had been measured in our laboratory on at least one occasion during the study period. Using these aforementioned criteria, 220 IBD patients (141 CD patients and 79 UC patients) were included in the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of each patient were determined, including age, duration of disease, disease location, disease behavior according to the Montreal classification, and IBD-related surgeries[18]. These data are provided in Table 1. Patients were treated with mesalamine, prednisone, azathioprine, infliximab or adalimumab based on the clinical assessment of the treating gastroenterologist following a step-up approach to therapy.

| Characteristics | CD (n = 141) | UC (n = 79) |

| Females | 74 (52) | 39 (49) |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 38.5 ± 12.8 | 47.0 ± 16.1 |

| Disease duration (yr, mean ± SD) | 9.8 ± 6.4 | 10.5 ± 7.2 |

| Location | L1: 63 (45) | E1: 8 (10) |

| L2: 29 (21) | E2: 39 (49) | |

| L3: 44 (31) | E3: 33 (41) | |

| L4: 4 (3) | ||

| Behavior | ||

| B1 | 56 (40) | |

| B2 | 37 (27) | |

| B3 | 46 (33) | |

| IBD surgery | 46 (33) | 2 (3) |

| VD supplementation | 30 (21) | 18 (23) |

VD serum concentration was measured in a fasting state in 196 IBD patients (124 CD patients and 72 UC patients) during the summer/autumn period and in 140 IBD patients (97 CD patients and 43 UC patients) during the winter/spring period.

The serum concentration of 25(OH)D was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1200) in a clinical biochemistry laboratory at the hospital. The parameters of the HPLC method were ultraviolet detection at 264 nm, flow rate of 1 mL/min, temperature of 40 °C, and analysis time of 10 min. This method measures 25 (OH)D3 and 25 (OH)D2.

The mean VD serum concentration and its correlation with health related quality of life were determined for each season separately.

The VD serum concentrations of 116 IBD patients (80 CD patients and 36 UC patients) were determined in both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period. In this subgroup, the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period were compared in terms of VD serum concentration and short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire (sIBDQ) score. The change in VD serum concentration between the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period was determined (∆VD). This sub-cohort was stratified into patients who had a normal VD serum concentration and those who did not. A VD serum concentration ≥ 30 ng/mL was considered to be normal. Patients with a VD serum concentration of 20-29.9 ng/mL were considered to be VD-insufficient and those with a VD serum concentration of < 20 ng/mL were considered to be VD-deficient. Patients were stratified according to their VD serum concentration into bins of 10 ng/mL.

Disease specific health related quality of life was measured at each visit using the sIBDQ[19]. In our center, this questionnaire is used as a part of the clinical routine for both CD and UC patients and those patients with sIBDQ scores ≥ 50 (maximum is 70) are considered to be in clinical remission[20]. The correlation between VD status and sIBDQ score was analyzed for all visits and for the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period separately. The mean sIBDQ score was also analyzed when patients were stratified according to their VD serum concentration into bins of 10 ng/mL. Finally, the effects of the summer/autumn period VD serum concentration and the mean of the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period VD serum concentrations on the winter/spring period sIBDQ score were analyzed.

In our collaborating center that treats osteoporosis, patients who are found to have a reduced bone mineral density by a DEXA scan are supplemented with 1000-1200 mg/d calcium and 400-1000 IU/d VD. The dose depends on the patient’s weight, compliance and the formulation used. For this study, to be considered as VD-supplemented, the patient must have been taking a minimum of 400 IU VD supplementation daily for at least 3 mo prior to the measurement of VD serum concentration (Table 1). In a subgroup of patients for whom VD serum concentration was measured in both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period, the effects of VD supplementation on the winter/spring period VD serum concentration, change in VD serum concentration from the summer/autumn period to the winter/spring period, and the winter/spring period sIBDQ score were analyzed.

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States).

Nominal and ordinal variables, such as clinical characteristics, VD status (sufficient/insufficient) and sIBDQ status (remission, activity) and season, were analyzed using the Chi square test with Yates’s correction. If any cell of the contingency table contained a value of less than 5, Fisher’s exact test was used instead.

Continuous variables (age, duration of disease, VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score) were analyzed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Separate summer/autumn period and winter/spring period mean VD serum concentrations and sIBDQ scores were compared among groups using Student’s T test or an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlations between VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score were tested using Pearson’s R correlation test. In a sub-cohort of patients for whom VD serum concentration was measured in both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period, the effect of VD supplementation on the winter/spring period VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score, as well as comparisons of VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score between the two seasons, were tested using the paired Student’s T test.

Statistical significance was considered at the level of P < 0.05. In multiple comparisons (ANOVA), Bonferroni’s correction was applied. If not stated otherwise, results are reported as mean ± SE.

The study was approved by the local ethical committee. All subjects gave written approval for their clinical data to be analyzed for research purposes.

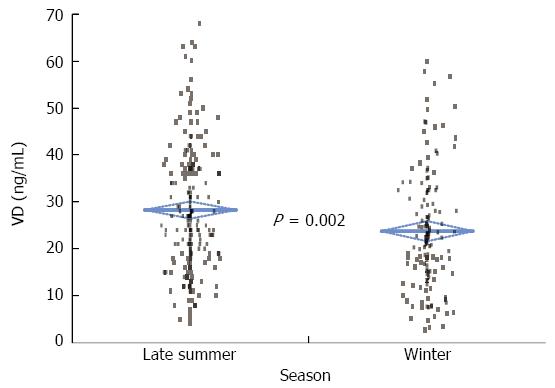

The mean VD serum concentration was significantly higher in the summer/autumn period than in the winter/spring period (28.2 ± 0.9 ng/mL vs 23.8 ± 1.1 ng/mL; P = 0.002) (Figure 1). This difference in VD serum concentration between seasons was observed in both CD (27.8 ± 1.2 ng/mL vs 23.2 ± 1.3 ng/mL, P = 0.01) and UC (29.0 ± 1.5 ng/mL vs 24.9 ± 2.0 ng/mL, P = 0.10) patients.

Patients were stratified according to their VD serum concentrations in the winter/spring period and the summer/autumn period into bins of 10 ng/mL. Table 2 shows the numbers of UC and CD patients in each bin.

| VD concentration (nmol/L) | IBD summer/autumn (n = 196) | CD summer/autumn (n = 124) | UC summer/autumn (n = 72) | IBD winter/spring (n = 140) | CD winter/spring (n = 97) | UC winter/spring (n = 43) |

| < 10 | 10 (5) | 8 (6) | 2 (3) | 22 (16) | 16 (16) | 6 (14) |

| 10-19.9 | 45 (23) | 28 (23) | 17 (24) | 37 (26) | 25 (26) | 12 (28) |

| 20-29.9 | 61 (31) | 38 (31) | 23 (32) | 43 (31) | 31 (32) | 12 (28) |

| 30-30.9 | 42 (21) | 27 (22) | 15 (21) | 21 (15) | 13 (13) | 8 (19) |

| 40-40.9 | 25 (13) | 16 (13) | 9 (13) | 11 (8) | 7 (7) | 4 (9) |

| 50-50.9 | 7 (4) | 4 (3) | 3 (4) | 6 (4) | 5 (5) | 1 (2) |

| > 60 | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| > 30 (normal) | 41% | 40% | 42% | 27% | 26% | 30% |

For UC patients, the mean sIBDQ score was significantly higher in the summer/autumn period than in the winter/spring period (54.8 ± 1.6 vs 51.3.0 ± 2.1; P = 0.02). The mean sIBDQ score of CD patients did not significantly differ between the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period (57.6 ± 1.1 vs 57.1 ± 1.1, P = 0.5).

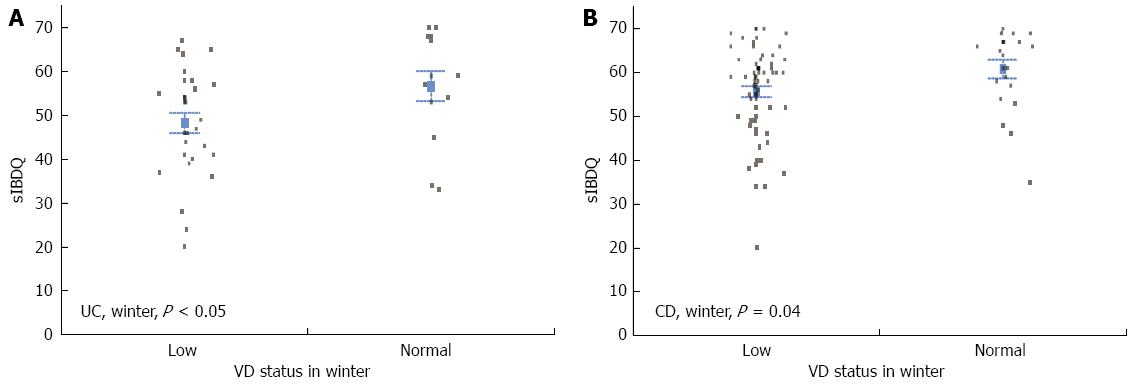

The mean sIBDQ score was significantly higher for UC patients that had a normal VD serum concentration than for those that had a low VD serum concentration (56.5 ± 1.9 vs 51.6 ± 1.5, P = 0.04). When the two seasons were examined separately, this difference was only significant in the winter/spring period (48.3 ± 2.3 vs 56.7 ± 3.4, P = 0.04), not in the summer/autumn period (54.8 ± 1.9 vs 56.4 ± 2.1, P = 0.6) (Figure 2A). In the winter/spring period, the mean sIBDQ score was significantly higher for CD patients that had a normal VD serum concentration than for those that had a low VD serum concentration (60.8 ± 2.14 vs 55.7 ± 1.25, P = 0.04) (Figure 2B). By contrast, there was no significant difference in the summer/autumn period (low VD serum concentration, 57.9 ± 1.2 vs normal VD serum concentration, 57.8 ± 1.6; P = 0.9) or when measurements from both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period were analyzed (low VD serum concentration, 56.8 ± 0.9 vs normal VD serum concentration, 58.8 ± 1.2; P = 0.18).

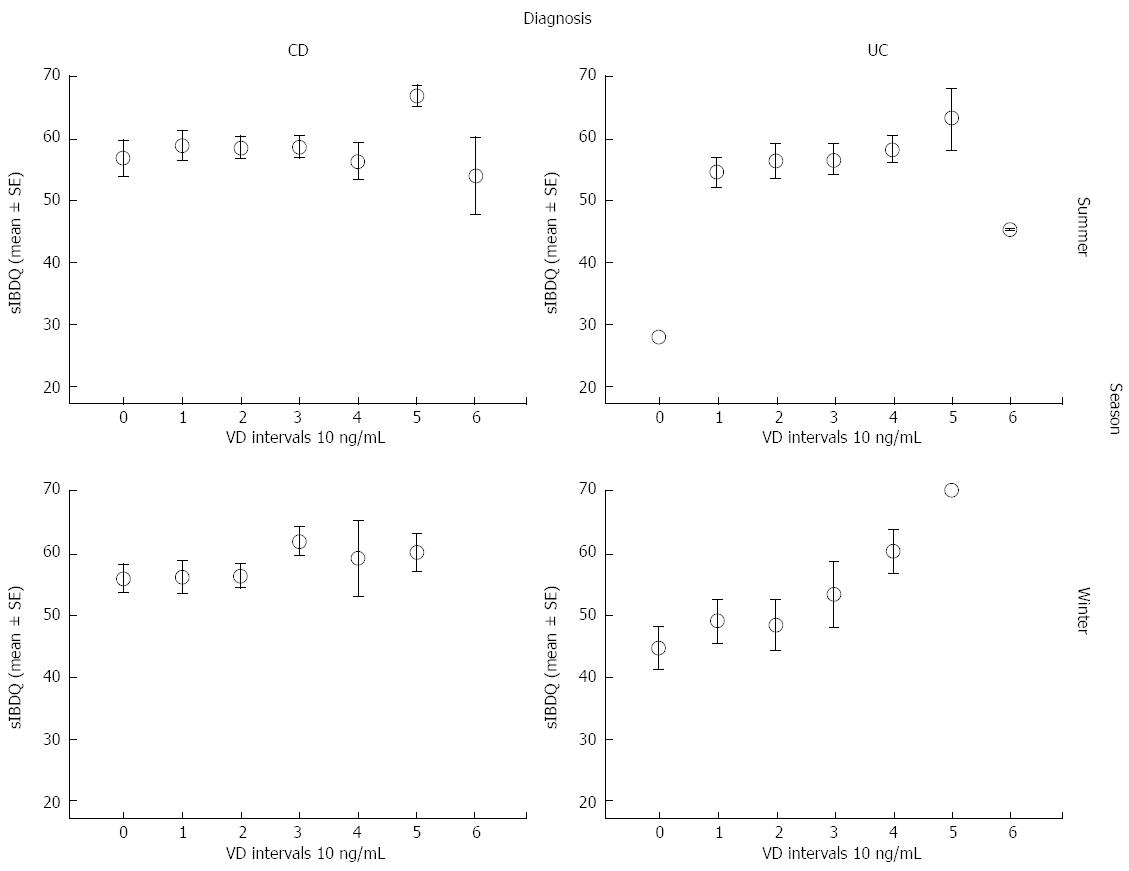

Next, we analyzed the mean sIBDQ scores of CD and UC patients that had been categorized according to their summer/autumn period and winter/spring period VD serum concentrations into bins of 10 ng/mL (Table 3, Figure 3).

| VD concentration (ng/mL) | sIBDQ (mean ± SE) | |||||

| CD | UC | |||||

| Summer/autumn (n= 107) | Winter/spring (n= 87) | All measurements (n= 194) | Summe/autumn (n= 72) | Winter/spring (n= 44) | All measurements (n= 116) | |

| < 10 | 56.6 ± 3.0 | 55.8 ± 2.2 | 56.1 ± 1.7 | 281 | 44.5 ± 3.5 | 42.1 ± 3.8a |

| 10-19.9 | 58.6 ± 2.3 | 56.0 ± 2.6 | 57.3 ± 1.7 | 54.3 ± 2.4 | 49.0 ± 3.4 | 51.7 ± 2.1 |

| 20-29.9 | 58.2 ± 1.7 | 56.1 ± 1.8 | 57.0 ± 1.2 | 56.9 ± 2.9 | 48.3 ± 4.2 | 53.0 ± 2.5 |

| 30-30.9 | 58.4 ± 1.7 | 61.8 ± 2.3 | 59.6 ± 1.4 | 56.3 ± 2.5 | 53.3 ± 5.1 | 55.1 ± 2.5 |

| 40-40.9 | 56.0 ± 3.0 | 59.0 ± 6.1 | 56.8 ± 2.7 | 58.0 ± 2.2 | 60.3 ± 3.5 | 58.9 ± 1.9 |

| 50-50.9 | 66.7 ± 1.7 | 60.0 ± 3.2 | 62.9 ± 2.3 | 63.0 ± 5.0 | 70 | 65.3 ± 3.7c |

| > 60 | 53.7 ± 6.2 | NA | 53.7 ± 6.2 | 451 | NA | 451 |

In UC patients, the mean sIBDQ score increased with VD serum concentration over the bins from < 10 ng/mL to 50-59.9 ng/mL. There were only three patients in the > 60 ng/mL bin and their mean sIBDQ score was low. This pattern of sIBDQ score increasing with VD serum concentration was also observed in CD patients. In UC patients, the mean sIBDQ score of patients in the lowest VD serum concentration bin (< 10 ng/mL) was significantly lower than those of patients in each of the other bins (P < 0.05), apart for the > 60 ng/mL bin. The mean sIBDQ score of UC patients with VD serum concentrations of 50-59.9 ng/mL was furthermore significantly higher than that of UC patients with VD serum concentrations of 10-19.9 ng/mL (P < 0.05).

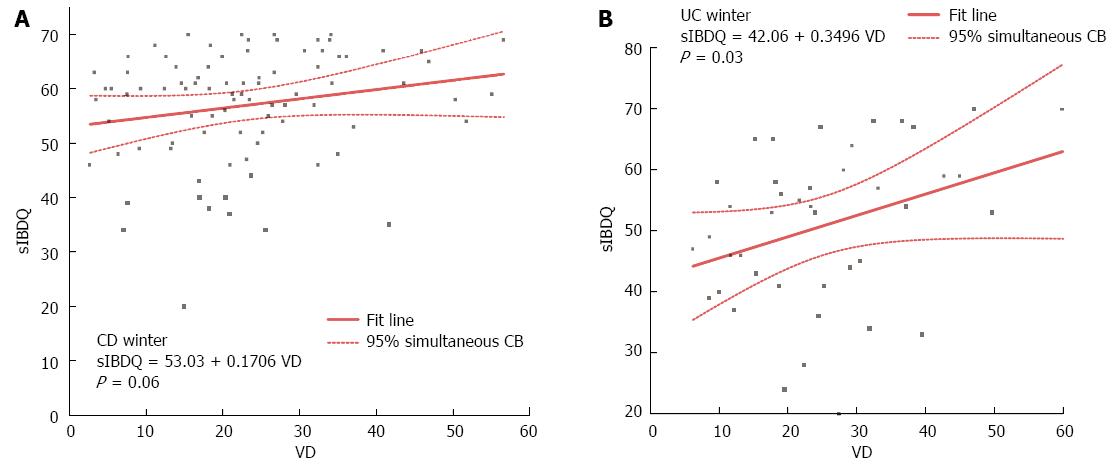

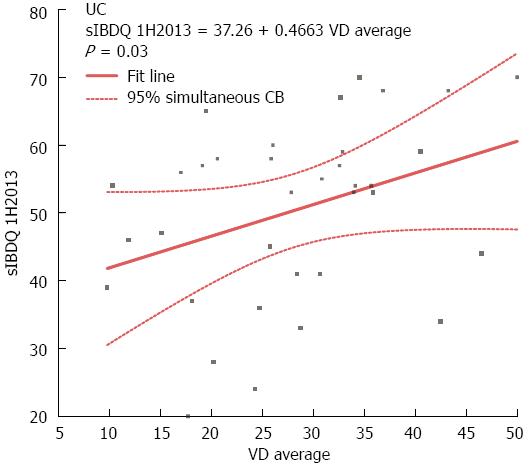

Next, we performed correlation analysis between VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score. There was no significant correlation between VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score in CD patients, although there was a trend towards significance in the winter/spring period (r = 0.17, P = 0.06; Figure 4A). By contrast, in UC patients, there was a significant correlation between VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score when both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period measurements were considered (r = 0.23, P = 0.02). This was also true when only the winter/spring period measurements were considered (r = 0.35, P = 0.03), but not when only the summer/autumn period measurements were considered (r = 0.1, P = 0.5) (Figure 4B).

Smoking, disease location, disease behavior and past IBD surgery did not significantly affect the association of VD serum concentrations and sIBDQ scores in either CD or UC patients.

Next, we analyzed the effect of VD supplementation on VD serum concentration in the IBD sub-cohort for whom measurements were collected in both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period. VD supplementation did not significantly affect the mean VD serum concentration in the summer/autumn period (supplemented patients, 30.2 ± 1.2 ng/mL vs non-supplemented patients, 26.8 ± 2.7 ng/mL, P = 0.6) or the winter/spring period (supplemented patients, 24.0 ± 1.6 ng/mL vs non-supplemented patients, 25.9 ± 2.5 ng/mL, P = 0.8). The mean decrease in VD serum concentration from the summer/autumn period to the winter/spring period was smaller in VD-supplemented patients than in non-supplemented patients (-1.0 ± 2.8 ng/mL vs -6.1 ± 1.5 ng/mL, P = 0.10). Table 4 shows similar analyses conducted on CD and UC patients separately.

| Characteristics(mean ± SE) | IBD | CD | UC | |||

| No VD supplementation (n= 90) | VD supplementation (n= 26) | NO VD supplementation (n= 64) | VD supplementation (n= 16) | NO VD supplementation (n= 26) | VD supplementation (n= 10) | |

| VD summer/autumn | 30.2 ± 1.4 | 26.8 ± 2.7 | 30.3 ± 1.7 | 27.1 ± 3.4 | 29.8 ± 2.7 | 26.4 ± 4.3 |

| sIBDQ summer/autumn | 56.7 ± 1.1 | 54.4. ± 2.1 | 57.5 ± 1.3 | 56.5 ± 2.6 | 54.3 ± 2.3 | 50.6 ± 3.7 |

| VD next winter/spring | 24.0 ± 1.6 | 25.9 ± 2.5 | 22.8 ± 1.6 | 26.4 ± 3.2 | 27.0 ± 2.5 | 25.0 ± 4.1 |

| sIBDQ next winter/spring | 56.8 ± 1.2 | 50.2 ± 2.3a | 58.6 ± 1.3 | 54.5 ± 2.5 | 53.0 ± 2.5 | 42.9 ± 4.2a |

| ∆ VD (winter/spring-summer/autumn) | -6.2 ± 1.5 | -1.0 ± 2.8 | -7.5 ± 1.6 | -0.7 ± 3.11 | -2.8 ± 3.2 | -1.4 ± 5.2 |

We analyzed the correlation between the change in VD serum concentration from the summer/autumn period to the winter/spring period and the winter/spring period sIBDQ scores. These two variables were significantly correlated in UC patients (r = 0.47, P = 0.03) but not in CD patients (r = 0.03, P = 0.8) (Figure 5).

Finally, we analyzed the winter/spring period sIBDQ scores of a subgroup of patients that had normal VD serum concentrations in both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period. In UC patients, the mean winter/spring period sIBDQ score of patients who had normal VD serum concentrations in both seasons was significantly higher than that of patients who did not (58.6 ± 2.4 vs 48.3 ± 4.8, P = 0.07). In CD patients, the mean sIBDQ scores of these two subgroups did not significantly differ.

During the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period, 28% and 42% of IBD patients in this study were VD-deficient (< 20 ng/mL), respectively. A further 31% were VD-insufficient (20-29.9 ng/mL) in both seasons. The prevalence of VD deficiency and insufficiency did not differ between CD and UC patients. This is in agreement with several other Western studies that reported that the prevalence of VD deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) was 18%-39% and 50%-57% at the end of the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period, respectively, and that about a further 35% of people were VD-insufficient (20-29.9 ng/mL)[12,21-23]. In the current study, the mean VD serum concentration was 4.2 ng/mL higher in the summer/autumn period than in the winter/spring period, which is similar to the seasonal difference reported by Bours (3 ng/mL)[23]. This difference in VD serum concentration between seasons is logical because production of VD3 depends heavily on exposure to sunshine. In the West, only a small amount of VD is obtained from the diet.

sIBDQ score, an indicator of disease specific health related quality of life, was significantly higher in the summer/autumn period than in the winter/spring period in UC patients (54.8 ± 1.6 vs 51.3 ± 2.1, P = 0.02) but not in CD patients. There is considerable controversy concerning seasonal variation in disease activity in CD and UC patients[24]. Some studies reported that the rate of flare-ups is low in the summer period, particularly in UC patients[25,26].

In the current study, a low VD serum concentration (< 30 ng/mL) was associated with a lower sIBDQ score in the winter/spring period in both CD and UC patients. In UC patients, the winter/spring period sIBDQ score correlated significantly with the winter/spring period VD serum concentration (r = 0.35) and the winter/spring period sIBDQ score correlated even more strongly with the mean of winter/spring period and the summer/autumn period VD serum concentrations (r = 0.46). In CD patients, there was a trend towards significant correlation between the winter/spring period sIBDQ score and the winter/spring period VD serum concentration (r = 0.17, P = 0.06).

Several recent studies made similar observations. In a recent trial of 504 IBD patients (403 CD and 101 UC), vitamin D deficiency was associated with lower sIBDQ in CD [regression coefficient -2.21, 95%CI: -4.1-(-0.33)] but not in UC (regression coefficient 0.41, 95%CI: -2.91-3.73), as well as with increased disease activity in CD (regression coefficient 1.07, 95%CI: 0.43-1.71)[11]. In a small study of CD patients, serum 25(OH)D3 concentration correlated with disease activity, as assessed by the Harvey-Bradshaw index (r = -0.484, P < 0.004)[14]. In another open label study of CD patients, after 12 wk of VD supplementation to a target serum VD concentration of more than 40 ng/mL, the mean IBDQ scores rose from baseline 156 ± 24 to 178 ± 22 points (P = 0.0006)[27]. Blanck recently reported that UC patients who were VD-deficient (< 30 ng/mL) were more likely to have high disease activity (68%, n = 19) than UC patients who were not (33%, n = 14) (P = 0.04)[13]. An inverse correlation between 25(OH)D concentration and calprotectin concentration has been reported in CD (Pearson's r = -0.35, P = 0.04), UC (r = -0.39, P = 0.04) and in all IBD together (r = -0.37, P = 0.003)[28]. IBD patients who were VD-insufficient (< 30 ng/mL) prior to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α treatment stopped this therapy earlier than patients who were not[29]. This effect was significant in patients who stopped treatment owing to the loss of response (HR = 3.49; 95%CI: 1.34-9.09) and was stronger for CD than for UC (HR = 2.38; 95%CI: 0.95-5.99). In a Dutch study of 316 IBD patients, low VD concentration, which was defined as the lowest quartile (< 16.8 ng/mL), was associated with increased disease activity[23].

In the current study, in all analyzed scenarios (UC/CD, summer/autumn period/winter/spring period), health related quality of life was the highest in patients with VD serum concentrations of 50-59 ng/mL, indicating a possible target level for therapeutic VD supplementation. In a study by Hawai, the highest 25(OH)D3 concentration recorded following natural exposure to ultraviolet B was 60 ng/mL and the authors recommended this as the upper limit when prescribing VD supplements[30].

With regards to a mechanistic explanation for our observations, VD might influence the disease activity and consequently the disease specific health related quality of life. The positive immunomodulatory effects of VD are well documented in many animal models of IBD[7]. VD also plays an important role in mucosal barrier homeostasis and preserving the integrity of epithelial junctions[31]. VD is also suggested to function in the physiological packaging of mucins in goblet cells[32].

In the current study, supplementation with a median of 800 IU/day VD (range: 400-1000 IU) did not influence the summer/autumn period VD serum concentrations. However, the change in VD serum concentration from the summer/autumn period to the winter/spring period was reduced from -6.2 ± 1.5 ng/mL in non-supplemented patients to -1.0 ± 2.8 ng/mL in VD-supplemented patients (P = 0.10, n.s.). Supplementation with such doses of VD for 4-6 mo did not affect disease related quality of life. In a small study on 55 IBD patients, the level of VD supplementation (mean, 371 IU/d) and 25[OH] serum concentration were only correlated during non-sunny months[33]. A small study from Ireland on a cohort of 58 CD patients identified VD supplementation (median, 340 IU/d) as an independent factor associated with adequate VD status in both the summer/autumn period and the winter/spring period[12]. In a recent study of 83 pediatric CD patients, supplementation with 400 IU or 2000 IU VD daily for 3 mo increased VD serum concentrations by a mean 2.8 ng/mL and 16 ng/mL, respectively, vs the baseline[34]. In an open label study on 19 CD patients, twenty-four weeks supplementation with up to 5000 IU/d vitamin D3 effectively raised serum 25(OH)D3 and reduced CDAI scores[27].

Although experimental animal studies and in vitro studies have provided evidence that VD supplementation may affect disease activity in CD and UC patients, there are limited clinical data. In a small double-blinded placebo-controlled randomized trial, oral supplementation of CD patients with 1200 IU/d VD3 non-significantly reduced the risk of relapse from 29% to 13% (P = 0.06)[16]. In another small study of 35 CD patients in remission, treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 and 25(OH)D3 significantly decreased clinical activity, as measured by the CD activity index, as well as mean C-reactive protein concentration[15].

The current study has several limitations. First, all analyses of health related quality of life were univariate, despite this variable being modulated by multiple factors. The study design and the numbers of patients in the UC and CD cohorts prevented multivariate analyses and confounding bias was possible. The correlation between VD serum concentration and sIBDQ score was not affected by disease location, disease behavior, previous IBD surgery or smoking. However, we did not examine the effects of disease medication. Second, the association between VD serum concentration and health related quality of life can be interpreted in several ways. A lower VD serum concentration may result in higher disease related quality of life. Alternatively, higher disease activity reflected in lower sIBDQ might result in a lower VD serum concentration level owing to reduced intestinal absorption and/or changes to diet or lifestyle. Third, the effects of VD supplementation are dose-dependent. The patients took 400, 800 or 1000 IU/d VD. To evaluate the effects of VD supplementation more precisely, patients need to be prescribed a standardized dose of VD in a prospective study.

To sum up, VD supplementation with adequate doses and saturation of 25(OH)D3 reserves might be a novel therapeutic approach for IBD that is simple, effective, safe and inexpensive. Based on the findings of this study, we believe that patients with UC, and perhaps also those with CD, who are VD-insufficient might benefit from VD supplementation with adequate doses to increase their VD serum concentration to around 50 ng/mL. It is likely that currently recommended doses of VD supplementation are too low to achieve this level and that higher doses are needed. Further studies are needed to confirm the association of VD with disease activity and to explore the optimal treatment protocol.

Vitamin D (VD) has strong immunomodulatory effects. The well known north-south geographical gradient of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) prevalence, genetic and epidemiology studies and animal model data suggest that VD plays a role in the pathogenesis of IBD.

There is limited and conflicting evidence of the influence of VD on disease activity in patients with IBD. Clinical data concerning the effect of VD supplementation on the disease activity and/or disease related quality of life are scarce.

In this study, VD-sufficient patients [25(OH)D > 30 ng/mL] had a higher health related quality of life (sIBDQ) in the winter/spring seasons. The effect was stronger among UC patients. In all analyzed scenarios (UC/CD, summer/winter), health related quality of life was the highest among patients with 25(OH)VD serum concentrations of 50-60 ng/mL. Supplementation with a median of 800 IU/d VD did not influence the VD serum concentration or the health related quality of life.

All data suggest that achieving target VD serum concentration of approximation 50-60 ng/mL might improve the quality of life of IBD patients. This could be achieved either with VD supplementation with adequate doses or with heliotherapy. However, the authors demonstrated that the currently recommended doses of VD supplementation (600-800 IU VD/d) are too low to achieve this target and higher doses are probably needed.

This paper offers important information that supplementation with currently recommended doses of VD did not influence health related quality of life in IBD patients.

P- Reviewer: Ando T, Howarth GS S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Raman M, Milestone AN, Walters JR, Hart AL, Ghosh S. Vitamin D and gastrointestinal diseases: inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4:49-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xue LN, Xu KQ, Zhang W, Wang Q, Wu J, Wang XY. Associations between vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:54-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Bao Y, Korzenik JR, Giovannucci EL, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Higher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:482-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nagpal S, Na S, Rathnachalam R. Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:662-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 638] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kamen DL, Tangpricha V. Vitamin D and molecular actions on the immune system: modulation of innate and autoimmunity. J Mol Med (Berl). 2010;88:441-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1678S-1688S. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Cantorna MT. Vitamin D, multiple sclerosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523:103-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lips P. Worldwide status of vitamin D nutrition. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:297-300. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hintzpeter B, Mensink GB, Thierfelder W, Müller MJ, Scheidt-Nave C. Vitamin D status and health correlates among German adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:1079-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pappa HM, Gordon CM, Saslowsky TM, Zholudev A, Horr B, Shih MC, Grand RJ. Vitamin D status in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1950-1961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ulitsky A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Naik A, Skaros S, Zadvornova Y, Binion DG, Issa M. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: association with disease activity and quality of life. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:308-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gilman J, Shanahan F, Cashman KD. Determinants of vitamin D status in adult Crohn’s disease patients, with particular emphasis on supplemental vitamin D use. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:889-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Blanck S, Aberra F. Vitamin d deficiency is associated with ulcerative colitis disease activity. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1698-1702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Joseph AJ, George B, Pulimood AB, Seshadri MS, Chacko A. 25 (OH) vitamin D level in Crohn’s disease: association with sun exposure & amp; disease activity. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:133-137. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Miheller P, Muzes G, Hritz I, Lakatos G, Pregun I, Lakatos PL, Herszényi L, Tulassay Z. Comparison of the effects of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D and 25 hydroxyvitamin D on bone pathology and disease activity in Crohn’s disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1656-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jørgensen SP, Agnholt J, Glerup H, Lyhne S, Villadsen GE, Hvas CL, Bartels LE, Kelsen J, Christensen LA, Dahlerup JF. Clinical trial: vitamin D3 treatment in Crohn’s disease - a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:377-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 295] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hiew HJ, Naghibi M, Wu J, Saunders J, Cummings F, Smith TR. Efficacy of High and Low Dose Oral Vitamin D Replacement Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Ibd): Single Centre Cohort. Gut. 2013;62:A2-A2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1571-1578. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hlavaty T, Persoons P, Vermeire S, Ferrante M, Pierik M, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Evaluation of short-term responsiveness and cutoff values of inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McCarthy D, Duggan P, O’Brien M, Kiely M, McCarthy J, Shanahan F, Cashman KD. Seasonality of vitamin D status and bone turnover in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1073-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Levin AD, Wadhera V, Leach ST, Woodhead HJ, Lemberg DA, Mendoza-Cruz AC, Day AS. Vitamin D deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:830-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bours PH, Wielders JP, Vermeijden JR, van de Wiel A. Seasonal variation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:2857-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vergara M, Fraga X, Casellas F, Bermejo B, Malagelada JR. Seasonal influence in exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1997;89:357-366. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Lewis JD, Aberra FN, Lichtenstein GR, Bilker WB, Brensinger C, Strom BL. Seasonal variation in flares of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:665-673. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Zeng L, Anderson FH. Seasonal change in the exacerbations of Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:79-82. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Yang L, Weaver V, Smith JP, Bingaman S, Hartman TJ, Cantorna MT. Therapeutic effect of vitamin d supplementation in a pilot study of Crohn’s patients. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2013;4:e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Garg M, Rosella O, Lubel JS, Gibson PR. Association of circulating vitamin D concentrations with intestinal but not systemic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2634-2643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zator ZA, Cantu SM, Konijeti GG, Nguyen DD, Sauk J, Yajnik V, Ananthakrishnan AN. Pretreatment 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and durability of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Binkley N, Novotny R, Krueger D, Kawahara T, Daida YG, Lensmeyer G, Hollis BW, Drezner MK. Low vitamin D status despite abundant sun exposure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2130-2135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, Ning G, Sun J, Hart J, Bissonnette M, Li YC. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208-G216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 502] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Paz HB, Tisdale AS, Danjo Y, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Argüeso P, Gipson IK. The role of calcium in mucin packaging within goblet cells. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77:69-75. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Grunbaum A, Holcroft C, Heilpern D, Gladman S, Burstein B, Menard M, Al-Abbad J, Cassoff J, MacNamara E, Gordon PH. Dynamics of vitamin D in patients with mild or inactive inflammatory bowel disease and their families. Nutr J. 2013;12:145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wingate KE, Jacobson K, Issenman R, Carroll M, Barker C, Israel D, Brill H, Weiler H, Barr SI, Li W. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in children with Crohn’s disease supplemented with either 2000 or 400 IU daily for 6 months: a randomized controlled study. J Pediatr. 2014;164:860-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |