Published online Nov 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15599

Revised: March 25, 2014

Accepted: May 12, 2014

Published online: November 14, 2014

Processing time: 346 Days and 19.8 Hours

Single incision laparoscopy (SIL) has become an emerging technology aiming at a further reduction of abdominal wall trauma in minimally invasive surgery. Available data is encouraging for the safe application of standardized SIL in a wide range of procedures in gastroenterology and hepatology. Compared to technically simple SIL procedures, the merit of SIL in advanced surgeries, such as liver or colorectal interventions, compared to conventional laparsocopy is self-evident without any doubt. SIL has already passed the learning curve and is routinely utilized in expert centers. This minimized approach has allowed to enter a new era of surgical management that can not be acceded without a fruitful combination of prudent training, consistent day-to-day work and enthusiastic motivation for technical innovations. Both, basic and novel technical specifics as well as particular procedures are described herein. The focus is on the most important surgical interventions in gastroenterology and aims at reviewing the current literature and shares our experience in a high volume center.

Core tip: This paper demonstrates the current state of single port laparoscopic surgery in gastroenterology and hepatology. The defined indications, standardized and novel technical specifics as well as the surgical strategy of particular procedures that are successfully performed are described herein according to the review of the international literature and the surgical standards developed at our department which is regarded one of the high-volume centers for single port surgery in the world (more than 2200 procedures).

- Citation: Mittermair C, Schirnhofer J, Brunner E, Pimpl K, Obrist C, Weiss M, Weiss HG. Single port laparoscopy in gastroenterology and hepatology: A fine step forward. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(42): 15599-15607

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i42/15599.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i42.15599

Throughout the past few years laparoscopic surgery has become a gold standard for many procedures in general surgery. This development is based on a reduced morbidity, shorter hospital stays, less postoperative pain and a quicker recoveries. The quest for even less invasive procedures has emphasized reducing the surgical trauma by minimizing the size or number of trocar incisions, with the ultimate goal to omit any visible scar at the abdominal wall. Single incision laparoscopic surgery (SIL) is part of recent developments in minimally invasive surgery to further allay abdominal wall trauma. Although the first steps in diagnostic laparoscopy were developed in the early 18th century using one single umbilical incision, technical limitations mandated the use of multiple trocars to perform minimally invasive surgery, at least for the purpose of therapeutic intervention. Almost two-hundred years later gynecologists adopted the transumbilical single incision approach for laparoscopic tubal ligation[1]. Recent advances in instrumentation provided the opportunity to revisit the SIL concept in technically more demanding procedures. Again, gynecologists pioneered the field with the first SIL hysterectomy[2] and SIL appendectomy in 1991[3]. General surgeons cautiously gravitated towards SIL by developing either extraumbilical one-trocar techniques[4] or gradually reducing the incisions for appendectomy by means of a transumbilical laparoscopic assisted technique[5]. The first report on SIL cholecystectomy is attributed to Paganini et al[6] but first published by Navarra et al[7].

Due to the slow development of new inventions within the medical society it took another ten years to introduce SIL in the daily surgical routine. Despite the contemplative reluctance of surgeons evaluating safety and feasibility, another main factor supported the advance of SIL, namely the scientific realization of the vision of performing surgery without any scar by utilizing the mouth, vagina or anus as the entrance to the surgical field - natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). This new methodology immediately attracted patients who stated that they would prefer NOTES over standard laparoscopy if the risks associated with the two approaches were similar[8]. This emphasizes the negative effects of surgical scars; despite proven risks of pain, bleeding, infection or hernia, often a patients first concern is to maintain a scarless cosmesis.

However, the concept of NOTES has several disadvantages and limitations with the currently available instruments, including abdominal spillage of gastric, urinary, or colonic contents, the necessity of many special instruments, difficulties in maintaining the spatial orientation, difficult tasks of viscerotomy closure with the additional risk of leakage from gastrotomy or colotomy. Therefore, NOTES has to be evaluated thoroughly in experimental models before it can be transposed into the clinical routine. Since there are so many obstacles in the development of NOTES, it is still in its early stages. On the other hand it has in turn stimulated a revived interest in SIL which represents an attractive alternative to both conventional laparoscopy and NOTES, by hiding the scar in the depth of the navel. In addition SIL can be performed with standard laparoscopic instruments and follows well known strategic surgical steps. Therefore, surgical outcomes and safety procedures are unaffected when it comes to the ease of converting a single-port surgery to a multi-port conventional laparoscopy immediately. It is noteworthy that the transvaginal and transrectal route, which were thoroughly studied to enable NOTES, are both under consideration to act as valid exit gates for specimen retrieval in SIL in order to keep the transumbilical incision as small as possible to further reduce postoperative pain. The use of mini-laparoscopic instruments via three millimeter multi-ports represent a technical alternative to SIL and NOTES aiming at the least possible surgical trauma. At present, even if no conclusive evidence based statement can be issued to exactly rank one method before the other this professional controversy fruitfully generates new views, approaches and strategies that spark the fire of surgical evolution.

The initial description for SIL was not homogenous. Many synonyms were used in the current literature, some of which were trademarks others more intuitive linked the transumbilical approach to a NOTES concept. Table 1 gives the most commonly used synonyms of SIL.

| Synonyms for single incision laparoscopy |

| Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery |

| Single incision laparoscopic surgery, SILS™ |

| Single port access surgery |

| Single port laparoscopy |

| Embryonic natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) |

| Single incision pediatric endosurgical techniques |

| Single-access-site laparoscopic surgery |

| Single-site-access laparoscopic surgery |

| Single site umbilical laparoscopy |

| One port umbilical surgery |

| Transumbilical endoscopic surgery |

| Trans-umbilical laparoscopic assisted |

| Natural orifice trans-umbilical surgery |

| Hybrid procedures (on the way to NOTES) |

Many professionals in the medical field remember the repeated warnings concerning risks related to laparoscopic surgery when this new method was compared to the open approach in former days. Arguments, such as increased risk of organ injury, a prolonged learning curve, or the need for young colleagues to have well-established training in open surgery before starting with new techniques, were declaimed like a mantra but finally failed to prove to be effectively true.

As a consequence, the indications for SIL surgery are the same as for standard laparoscopic surgery (LS). This excludes all forms of general peritonitis and patients whose medical history does not allow the application of a pneumoperitoneum. LS in small children utilizes special instruments, this has to be taken into account even more with SIL, which requires a working distance of at least ten centimeters from the entrance port to the target to enable sufficient triangulation.

Preexisting scars at the abdominal wall are no longer a contraindication for this technique, but may, at least, counterbalance the cosmetic advantage. Otherwise, preexisting scars may be indicators for intraabdominal adhesions. It is the open approach of SIL that allows for best view and devision of adhesions with immediate effect since no additional port site has to be prepared bluntly to deliver working instruments.

Starting with SIL procedures represents a challenge for both, beginners and experienced laparoscopic surgeons since this technique initially increases the individual mental workload and reduces the surgical task performance compared to times in the past when standard laparoscopy first broke in the field of open surgery. However, for surgical novices this moot difference in performance is reduced within some procedures which could be demonstrated in various performance studies. At the end, training in SIL appears to result in better skill acquisition and these improved surgical abilities can be utilized to carry out both SILC and LC, whereas training in LC fails to have the same effect[9]. The same is true for experienced laparoscopic surgeons.

Training therefore is paramount to prevent a free-style obstacle race during the first SIL procedures, which unfortunately ends up discrediting the method rather than redounding to the patients’ advantage. Prudent proctoring might be helpful for surgeons to get SIL skills in their repertoire[10].

As there is a significant difference in the level of difficulty over all SIL procedures, a universally valid number of required procedures for passing the learning curve can not be stated. However, the available data suggest a number of 10 to 50 cases would be necessary to traverse the vulnerable period during take off with SIL.

Methods of entering the umbilicus can vary. Most surgeons prefer cutting vertically in the groove of the navel to hide the scar[11]. At the end of the procedure a virtually scarless aspect can be achieved by incorporation of the incision within the restored umbilical crease using an intracutaneous running suture that combines a linear with a purse-string closure. Others advocate cutting at the upper margin of the umbilicus with a slight lengthening to both sides resulting in a omega-shaped line[12]. In the standing position this scar is hardly detectable after surgery. A transumbilical horizontal incision is advocated by others[13] to possibly prevent postoperative pain by non-transection of cutaneous nerves that take course from lateral.

However, for the removal of a larger specimen extending the scar sometimes is necessary. In this case, we prefer to exceed the arch of the umbilicus at the lower margin for achieving a satisfying cosmetic result. The positive correlation between length of incision and risk for wound complications has been scientifically proven[14] for incisions longer than four centimeters in open surgery. Assumably, for SIL and conventional laparoscopy a similar correlation should exist although available data can not convincingly identify any thresholds. In our experience the better ability to perform a fascial closure under direct vision after SIL might outweigh the risk of a longer incision compared to conventional laparoscopy. An incidence of 5.8% incisional hernia after SIL cholecystectomy as published by Alptekin et al[15] possibly embodies a substantial number of preexisting fascial defects adjacent to the incision that failed to be identified during wound closure. In our patient population, a prevalence of preexisting small umbilical hernias or fascial defects is documented in approximately 40%. These defects can be identified more accurately by a transumbilical approach than in LS. The fascial closure in SIL is still under debate, a general recommendation for the use of non-absorbable sutures or meshes can not be given yet. In our hands, the use of slowly absorbable sutures for fascial closure results in an acceptable low rate of umbilical complications, including hernia[11].

The reduction of incisional trauma by using one single approach was first achieved by use of an optical trocar. However, this technique had limitations in the surgical performance which mandated the use of additional trocars and suspending sutures. Therefore, low profile trocars were deployed through separated fascial incisions. Later on, single-port devices enclosing three to four working channels or a gel cap were developed to bring three or more instruments through one fascial incision (Figure 1). Sufficient sealing of the pneumoperitoneum is of paramount importance for SIL that is provided by all single-port devices. These port devices slightly increase the direct procedural costs but reduce the risk for wound complications significantly[11]. In order to be even more cost effective, hand-made ports are developed that combine a wound protecting foil with a sterile surgical glove where the fingertips serve as points of access, yet maintain an airtight seal for insufflation. As an alternative, reusable SIL ports are available now that show a break-even in procedural costs after 15-20 interventions when compared to conventional laparoscopy.

A negative characteristic feature of the SIL technique can be experienced when instruments clash inside and outside the body due to the deflection at a single fulcrum at the umbilicus. To diminish this awkward effect, several different strategies can be pursued.

First, crossing the instruments leads to a virtual exchange of the right and left side, meaning that the instrument that is deployed with the right hand is positioned at the left side of the operative field and vice versa. In this situation, the use of at least one articulating or bent instrument reestablishes triangulation and prevents clashing of hands outside. Furthermore, it is an advantage to deploy longer graspers to reach the target via the longer curved way. Handling with pre-bent instruments seems easier when starting with SIL. However, articulating instruments with rotating tips enable more degrees of freedom for complex movements in advanced procedures. The bent or articulating instrument should always be used in the supporting hand whereas the straight instrument is in the operating one to facilitate more demanding performance tasks, such as dissection, sealing, clipping or suturing.

Second, double-curved instruments can be used. These instruments provide instrument guidance for both hands when used effectively. This advance in handling is counterbalanced by the fact that instrument movement in a linear axis is hardly possible.

Third, a variety of different retracting devices has been developed. Of these, different suspending sutures proved to be of particular use in the exposition of the operating field. Self-made devices built of sutures or wires allow for flexible or static retraction in a string puppet like fashion whereas intra-abdominal retractors are available (EndoGrab, EndoLift, Virtual Ports, Israel; VERSA Lifter, TPEA Lifter, Surgical Perspective, France) to be positioned more versatile to act as virtual ports.

Fourth, the most sophisticated devices for SIL are operative platforms, such as the disposable SPIDER™ (Single Port Instrument Delivery Extended Reach, TransEnterix, DACH Medical) device or the da Vinci Single-Site™ Instrumentation robot (Intuitive Surgical, Inc). These systems offer all possible degrees of freedom for dissection or retraction. The SPIDER™ delivers two flexible instruments as graspers, hooks or scissors together with a five millimeter camera and an additional straight trocar through a four channel shaft. The da Vinci SI robot additionally offers stereoscopic vision and subtle guidance of instruments. At present, higher costs and longer operation times due to laborious installation impede wide acceptance of this robotic platform at least for simple SIL procedures. It has to be investigated if those platforms are able to justify their inclusion in more advanced applications, such as SIL liver or bile duct surgery.

Along with the selection of useful working instruments and retraction devices, choosing an appropriate camera system with a corresponding optic plays a crucial role. The insertion of an extra long camera system with a 30° or 45° optic facilitates instrument handling outside the body enormously. Laparoscopes with a flexible tip proved to be helpful in various situations but require subtle guidance.

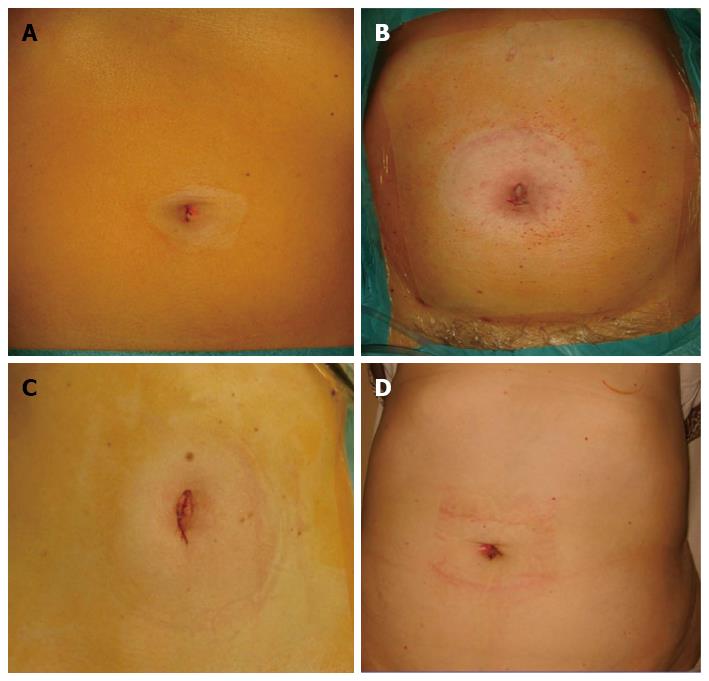

Within the last five years more than 2000 transumbilical SIL procedures were performed in our Department. Table 2 shows the number of patients with regard to the specified SIL procedures. Figure 2 demonstrates representative samples of postoperative views following simple and advanced SIL interventions.

| Transumbilical SIL procedures | n |

| Cholecystectomies | 801 |

| Inguinal hernia repairs | 525 |

| Colorectal resections | 376 |

| Appendectomies | 274 |

| Liver resections | 40 |

| Small bowel resections | 29 |

| Fundoplications | 21 |

| Gastric resections | 21 |

| Pancreas resections | 9 |

| Adrenalectomies | 9 |

| Others | 102 |

| Total | 2207 |

A brief description of the current scientific evidence and some technical refinements is given for the respective indications as follows.

In 1991 Pelosi described the first successful SIL-appendicectomy (AE)[3]. This approach has the potential to offer the same benefits commonly associated with laparoscopic surgery in terms of recovery and pain with, perhaps, an even better cosmetic result. It is regarded the easiest of the surgical standard SIL procedures with the shortest learning curve[10]. For novices regarding SIL technique the limitation in working angles require some adjustment in instrument handling, therefore the use of at least one bendable instrument is recommended.

Data of randomized controlled studies, comparative studies and meta-analyses revealed that SIL-AE compared to the conventional laparoscopic approach produces longer operative times in children and obese and therefore resulting in greater costs. In contrast, less pain and faster recovery is reported in cases with perforation when operated by means of SIL[16-20]. SIL-AE does not increase the rate of complications and therefore represents a valuable alternative to conventional laparoscopic appendectomy with the benefit of better cosmetic satisfaction among patients.

At our department, SIL-AE has become the standard method for appendectomy in nearly all cases of acute appendicitis. This procedure, in our hands, turned out to be ideal for proctoring residents and novices in this technique.

As mentioned above, the first official presentation of SIL-cholecystectomy (CHE) by Paganini and Navarra dates back almost 20 years. A variety of different techniques have been described so far, of which some obviously ignore the rules of safety by compromising the standard dissection in the triangle of Calot. However, more or less sophisticated variations have been published using sutures, wires, endohooks, SPIDER™, robotics etc. All of these variations proved to be safe and feasible for SIL-CHE, at least in non-acute cases. The initial enthusiasm for SIL-CHE resulted in a high number of low profile feasibility studies that provoked justified skepticism. The lack of sufficient data to clearly prove any inferiority or benefit still hampers scientific conclusion. The current evidence shows that SIL-CHE offers a safe alternative to conventional cholecystectomy with a comparable profile in intra- and postoperative complications[21-23]. The need for a longer operating time is balanced by a trend to lower postoperative pain and improved patient satisfaction.

We perform SIL-CHE for acute and non acute gallbladder disease in all patients eligible for laparoscopic surgery. Intraoperative cholangiography, a rendez-vous bile duct exploration with intraoperative ERCP/EPT or stone removal can already be performed easily with this approach.

Starting at 2008[24-26] various SIL techniques have been described for resection of the right, transverse or left colon, as well as rectal resections. The umbilicus as site of port placement is suitable in all SIL-colorectal resection (CR) procedures and can provide access to all parts of the colorectal frame, solely the dissection at the splenic flexure can be challenging in some patients due to a high distance between these two organs. Another benefit of this access is the possibility of harvesting even large and bulky specimens. An incision length of five centimeters can be easily hidden in the umbilical arch, but allows removing bulky colonic specimen, as in sigmoid resection for recurrent diverticulitis.

Aiming at a reduction of risks for wound complications in SIL-CR surgery an access via a Pfannenstiel incision was described and the procedures could be carried out successfully[27]. The enhanced distance to the splenic flexure was no problem in this series of three patients.

Access via the prospective stoma site is an obvious consideration when stoma creation is planned, as in many patients with rectum resection and TME. This technique is feasible and provides excellent exposure to the ascending colon, sigma and rectum[28].

The best site for specimen retrieval is currently under debate. The advocates of the transvaginal route favor that site for the negligible amount of pain reported postoperatively and the mere unlimited widening to extract bulky organs. In male patients the transrectal route might serve as a sufficient retrieval site not only after deep rectal resections but also for left side colectomies. Considerations regarding infection of the surgical track, seeding of pathologic cells or functional impairment of the healthy organ that thereby suffers from additional iatrogenic trauma have still not been assessed scientifically.

Randomized controlled trials between SIL and conventional CR indicate a comparable outcome which favors SIL-CR in terms of shorter hospital stay and a trend to lower pain. Therefore SIL-CR might serve as a safe alternative to the conventional approach in a selected group of non-obese patients[29-33].

Depending on the type of resection, different surgical steps are crucial: (1) Right hemicolectomy and ileocolic resection. The patient is placed in the supine position with the surgeons standing on the left. Dissection and intestinal transection do not differ from LS. After completing the dissection the specimen is placed in a tearproof retrieval bag and pulled out through the umbilicus. This maneuver provides additional skin protection and is also an effective method to protect the peritoneum from any bacterial or tumor cell contamination through the spillage of squeezed fluid. Two different techniques of an anastomosis can be carried out: First, the corresponding sides are pulled out through the umbilicus and the anastomosis can be carried out externally. However, swelling of the bowel may complicate the repositioning of the anastomosis, also missing the orientation of the mesentery may lead to a distortion of the two intestinal ends. Second, the anastomosis technique is performed intra-corporeally as described by Morales-Conde[13]. Both ends of the intestine are fixed by a retracting suture and the anastomosis is conducted via a stapler. The insertion site is closed by a transverse running suture. This avoids traction of the pedicle of the mesentery of the corresponding intestinal segments as it might happen during the extracorporeal technique. An additional widening of the fascial incision can be prevented; and (2) Left colectomy, low anterior resection, total colectomy, and proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. The patient is placed on a split leg table with the operating team on the right side. Again, dissection and intestinal transection can be carried out as known from LS. After completion of the dissection, the specimen is caught in a tearproof bag as mentioned above and extracted through the umbilicus. Transanal anastomosis is carried out according to the technique of LS.

In contrast to the above mentioned operative techniques, only few data concerning SIL-L are available. Most of the published data are case reports or extended case reports with literature reviews. Due to the demanding technique of laparoscopic liver surgery, the step forward towards SIL was made very cautiously. In 2009 we first published our limited experience of SIL-liver resections (L)[24].

Interestingly, some of the first published procedures performed in this technique were resections for malignancies[34,35]. Technical papers demonstrating feasibility and safety of the particular resection in small patients cohorts were presented thereafter. At present the largest series was conducted by Shetty et al[36] and Choi et al[37] dealing with liver resections for hepatocellular carcinoma including right and left hepatectomies and with hepatectomies for liver transplantation. These data prove feasibility and safety of this surgical high-end performance in selected patients.

To date our group has conducted 40 SIL-L procedures, with a range from simple fenestration of liver cysts to highly demanding procedures including right hepatectomy or multiple resections in posterior segments.

In most of these cases, patients were placed in an anti-Trendelenburg position and the access was accomplished via an umbilical port. Pathologies in segment IVb, VII or VIII are ideally approached from below the right costal margin to provide a sufficient view. As mentioned before, adequate exposition of the operating field is mandatory and can be achieved by appropriate table angulation. Particular operative steps concerning dissection and vessel ligation do not differ from standard laparoscopic liver resection; specimen retrieval should always be carried out by use of a retrieval bag in parenchymatous organ resections.

Available data suggest the feasibility of this technique in the hands of an expert in selected cases. However, it has to be stressed that the clinical application of this technique is in need of an expertise in all three scopes, SIL, laparoscopic and open liver surgery, respectively.

Single incision laparoscopic pancreas resection represents a very exotic ambit of this technique. As standard laparoscopic pancreas surgery is among the most demanding procedures in minimal invasive surgery, the application of SIL-pancreas resections (P) into clinical routine has, understandably, not yet progressed without conflicts. This is represented by a low number of available data, involving only five published case reports. Authors report on distal pancreatectomy and necrosectomy, concluding that the technique is feasible[38-40].

We have so far conducted 9 SIL-P procedures at our institution, including two enucleations of small endocrine tumours and seven distal pancreatectomies for cancer. This patient group, of course, is highly selected concerning patients’ parameters (body mass index, age, and American Society of Anesthesiologists classification), tumour size, and tumour localisation. For optimal exposition of the operating field, all patients were placed in a right lateral position. Further improvement could be achieved by the use of retraction systems and the appropriate tilting of the table.

Again, operative steps in tissue preparation, handling and dissection did not differ from those in standard laparoscopic pancreas surgery. It has to be emphasized that profound skills in laparoscopic pancreas surgery are indispensable for a safe implication of SIL-P into clinical routine.

SIL-gastroesophageal (GE) procedures include a variety of different procedures with a clear focus on the stomach. As this review does not focus on metabolic procedures we steer clear of dealing with SIL sleeve gastrectomy, SIL gastric band application and SIL gastric bypass in detail. However, it has to be mentioned that these procedures represent a numerous variety of SIL procedures which are widely used in both, clinical and scientific application, yet.

SIL surgery at the esophagus is in a very early stage. Clinical application of classic esophageal resection has been documented only in few cases[41]. Procedures for the treatment of achalasia and gastro-esophageal reflux are far more common. The development of these procedures is strongly advocated by Ross et al[42]. This group oversees a high number of SIL-GE procedures and has evaluated SIL fundoplication (SIL-F) to be as safe as “classic” laparoscopic fundoplication with comparable remission of symptoms but superior cosmesis. They have published encouraging data about SIL Heller myotomy with anterior fundoplication for achalasia and the learning curve in SIL-F.

SIL gastric procedures (SIL-G) are mainly narrowed down to the resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) or small benign lesions. These procedures can, depending on the localisation of the lesion, be performed safely and with few technical adjustments compared to LS[43]. Procedures for gastric cancer are rare which is mainly owed to the technically demanding step of lymph node dissection. However a first case report could at least demonstrate the feasibility[44].

Our experience in SIL-GE is limited to a total of 41 procedures (21 cases of each, SIL-F and SIL-G, respectively). The patients in our setting are placed as in laparoscopic procedures with the surgeon standing between the patient’s legs. However, tissue dissection slightly differs from standard LS: Organ retraction for SIL-F is more challenging, as many available transumbilical systems are not suitable for retracting fatty livers. In our hands, this was best facilitated with the use of the Endo-Sail (AMI, Austria). Other technical challenges are the closeness of the instruments’ working area to the pancreas, endangering possible clashing with this vulnerable organ, and the length of the instruments required to reach the esophagus in order to perform a proper intra-thoracic dissection. In addition, ideal construction of the gastric wrap with intracorporeal suturing is demanding. Nowadays, SIL-G is routinely applied in GIST if the localisation of the lesion is accessible by a minimally invasive approach. The same is true for perforated duodenal ulcer. However, gastric cancer with the necessity of an extended lymph node dissection should be performed only in well designed study settings for oncological reasons.

SIL surgery represents an important step forward - towards the ultimate surgeon’s goal to bypass the abdominal wall thereby providing scarless visceral procedures. Available data is encouraging for the safe application of SIL in a wide range of procedures in gastroenterology and hepatology. Although pro and cons of SIL compared to LS in technically simple procedures have to be further assessed scientifically in detail, the merit of SIL in advanced interventions, such as liver or demanding colorectal surgery, is self-evident without any doubt. SIL has already entered a new era of surgical management that can not be acceded without a fruitful combination of prudent training, consistent day-to-day work and enthusiastic motivation for technical innovations.

Finally, by means of improving our surgical skills, utilizing novel techniques without being commercially tempted, and strictly focusing on the clinical outcome, the time is ripe to offer our patients this less invasive, better surgery.

P- Reviewer: Pan WS, Takao S S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Siegler AM. An instrument to aid tubal sterilization by laparoscopy. Fertil Steril. 1972;23:367-368. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using a single umbilical puncture. N J Med. 1991;88:721-726. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Wolenski M, Markus E, Pelosi MA. Laparoscopic appendectomy incidental to gynecologic procedures. Todays OR Nurse. 1991;13:12-18. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Inoue H, Takeshita K, Endo M. Single-port laparoscopy assisted appendectomy under local pneumoperitoneum condition. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:714-716. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kala Z, Hanke I, Neumann C. [A modified technic in laparoscopy-assisted appendectomy--a transumbilical approach through a single port]. Rozhl Chir. 1996;75:15-18. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Paganini A, Lomonto D, Navordino M. One port laparoscopic cholecystectomy in selected patients. Luxemburg: Third International Congress on New Technology in Surgery 1995; 11-17. |

| 7. | Navarra G, Pozza E, Occhionorelli S, Carcoforo P, Donini I. One-wound laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84:695. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Varadarajulu S, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER. Patient perception of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery as a technique for cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:854-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kwasnicki RM, Aggarwal R, Lewis TM, Purkayastha S, Darzi A, Paraskeva PA. A comparison of skill acquisition and transfer in single incision and multi-port laparoscopic surgery. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ahmed I, Ciancio F, Ferrara V, Jorgensen LN, Mann O, Morales-Conde S, Paraskeva P, Vestweber B, Weiss H. Current status of single-incision laparoscopic surgery: European experts’ views. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:194-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Weiss HG, Brunner W, Biebl MO, Schirnhofer J, Pimpl K, Mittermair C, Obrist C, Brunner E, Hell T. Wound complications in 1145 consecutive transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic procedures. Ann Surg. 2014;259:89-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang CK, Tsai JC, Lo CH, Houng JY, Chen YS, Chi SC, Lee PH. Preliminary surgical results of single-incision transumbilical laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;21:391-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Morales-Conde S, Barranco A, Socas M, Méndez C, Alarcón I, Cañete J, Padillo FJ. Improving the advantages of single port in right hemicolectomy: analysis of the results of pure transumbilical approach with intracorporeal anastomosis. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;2012:874172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Laurent C, Leblanc F, Bretagnol F, Capdepont M, Rullier E. Long-term wound advantages of the laparoscopic approach in rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:903-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alptekin H, Yilmaz H, Acar F, Kafali ME, Sahin M. Incisional hernia rate may increase after single-port cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:731-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cai YL, Xiong XZ, Wu SJ, Cheng Y, Lu J, Zhang J, Lin YX, Cheng NS. Single-incision laparoscopic appendectomy vs conventional laparoscopic appendectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5165-5173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li P, Chen ZH, Li QG, Qiao T, Tian YY, Wang DR. Safety and efficacy of single-incision laparoscopic surgery for appendectomies: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4072-4082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gao J, Li P, Li Q, Tang D, Wang DR. Comparison between single-incision and conventional three-port laparoscopic appendectomy: a meta-analysis from eight RCTs. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:1319-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Frutos MD, Abrisqueta J, Lujan J, Abellan I, Parrilla P. Randomized prospective study to compare laparoscopic appendectomy versus umbilical single-incision appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2013;257:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kye BH, Lee J, Kim W, Kim D, Lee D. Comparative study between single-incision and three-port laparoscopic appendectomy: a prospective randomized trial. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hao L, Liu M, Zhu H, Li Z. Single-incision versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with uncomplicated gallbladder disease: a meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:487-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wu XS, Shi LB, Gu J, Dong P, Lu JH, Li ML, Mu JS, Wu WG, Yang JH, Ding QC. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus multi-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2013;23:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Trastulli S, Cirocchi R, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Santoro A, Parisi A, Noya G, Boselli C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing single-incision versus conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:191-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brunner W, Schirnhofer J, Waldstein-Wartenberg N, Frass R, Pimpl K, Weiss H. New: Single-incision transumbilical laparoscopic surgery. Eur Surg. 2009;3:98-103. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Remzi FH, Kirat HT, Kaouk JH, Geisler DP. Single-port laparoscopy in colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:823-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bucher P, Pugin F, Morel P. Single port access laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1013-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ragupathi M, Ramos-Valadez DI, Yaakovian MD, Haas EM. Single-incision laparoscopic colectomy: a novel approach through a Pfannenstiel incision. Tech Coloproctol. 2011;15:61-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Choi BJ, Lee SC, Kang WK. Single-port laparoscopic total mesorectal excision with transanal resection (transabdominal transanal resection) for low rectal cancer: initial experience with 22 cases. Int J Surg. 2013;11:858-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Mereu A, Binda B, Brachini G, Trombetta S. Standard laparoscopic versus single-incision laparoscopic colectomy for cancer: early results of a randomized prospective study. Am J Surg. 2012;204:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Egi H, Hattori M, Hinoi T, Takakura Y, Kawaguchi Y, Shimomura M, Tokunaga M, Adachi T, Urushihara T, Itamoto T. Single-port laparoscopic colectomy versus conventional laparoscopic colectomy for colon cancer: a comparison of surgical results. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fung AK, Aly EH. Systematic review of single-incision laparoscopic colonic surgery. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1353-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vasilakis V, Clark CE, Liasis L, Papaconstantinou HT. Noncosmetic benefits of single-incision laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy for diverticular disease: a case-matched comparison with multiport laparoscopic technique. J Surg Res. 2013;180:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kwag SJ, Kim JG, Oh ST, Kang WK. Single incision vs conventional laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer: a case-matched study. Am J Surg. 2013;206:320-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kobayashi S, Nagano H, Marubashi S, Wada H, Eguchi H, Takeda Y, Tanemura M, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M. A single-incision laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: initial experience in a Japanese patient. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Belli G, Fantini C, D’Agostino A, Cioffi L, Russo G, Belli A, Limongelli P. Laparoendoscopic single site liver resection for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: first technical note. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:e166-e168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Shetty GS, You YK, Choi HJ, Na GH, Hong TH, Kim DG. Extending the limitations of liver surgery: outcomes of initial human experience in a high-volume center performing single-port laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1602-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Choi HJ, You YK, Na GH, Hong TH, Shetty GS, Kim DG. Single-port laparoscopy-assisted donor right hepatectomy in living donor liver transplantation: sensible approach or unnecessary hindrance. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:347-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Barbaros U, Sümer A, Demirel T, Karakullukçu N, Batman B, Içscan Y, Sarıçam G, Serin K, Loh WL, Dinççağ A. Single incision laparoscopic pancreas resection for pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma. JSLS. 2010;14:566-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kuroki T, Adachi T, Okamoto T, Kanematsu T. Single-incision laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1022-1024. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Subramaniam D, Dunn WK, Simpson J. Novel use of a single port laparoscopic surgery device for minimally invasive pancreatic necrosectomy. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94:438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chu XY, Xue ZQ, Jia BQ, Du XH, Zhang LB, Hou XB. [Combination of single-port thoracoscopy and laparoscopy for the treatment of esophageal carcinoma: report of 6 cases]. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2011;14:689-691. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Ross S, Roddenbery A, Luberice K, Paul H, Farrior T, Vice M, Patel K, Rosemurgy A. Laparoendoscopic single site (LESS) vs. conventional laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD: is there a difference. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:538-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ong E, Abrams AI, Lee E, Jones C. Single-incision sleeve gastrectomy for successful treatment of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. JSLS. 2013;17:471-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ertem M, Ozveri E, Gok H, Ozben V. Single incision laparoscopic total gastrectomy and d2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer using a four-access single port: the first experience. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:504549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |