Published online Jan 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.1114

Revised: September 7, 2013

Accepted: September 16, 2013

Published online: January 28, 2014

Processing time: 181 Days and 20.9 Hours

Achalasia cardia is an idiopathic disease that occurs as a result of inflammation and degeneration of myenteric plexi leading to the loss of postganglionic inhibitory neurons required for relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and peristalsis of the esophagus. The main symptoms of achalasia are dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain and weight loss. At present, there are three main hypotheses regarding etiology of achalasia cardia which are under consideration, these are genetic, infectious and autoimmune. Genetic theory is one of the most widely discussed. Case report given below represents an inheritable case of achalasia cardia which was not diagnosed for a long time in an 81-year-old woman and her 58-year-old daughter.

Core tip: We report an inheritable case of achalasia cardia in an 81-year-old woman and her 58-year-old daughter with early manifestation of the disease at 23 and 25 years of age, respectively, and further progression of achalasia cardia which led to its decompensation and resulted in gastrostomy in the woman which was performed when she was 79-year-old.

- Citation: Evsyutina YV, Trukhmanov AS, Ivashkin VT. Family case of achalasia cardia: Case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(4): 1114-1118

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i4/1114.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i4.1114

Achalasia cardia is a primary esophageal motility disorder with involvement of the Auerbach’s intermuscular plexus[1]. Achalasia cardia is considered a very rare disease, its incidence rate is 10 cases per 100000 population, and morbidity rate is 1 per 100000 population[2]. Achalasia cardia is diagnosed in adults most frequently in the age group of 25 to 60 years. Although the disease was first described by Thomas Williams, an English doctor, in 1674[3], the etiology of achalasia cardia still remains unknown. Genetic theory is one of the possible theories considered as the pathogenesis of achalasia cardia. We report an inheritable case of achalasia cardia which was not diagnosed for a long time in mother and her daughter.

Patient A, a 58-year-old, was admitted to the Clinic of the First Moscow State Medical University on March 2013 with the following complaints: dysphagia (to solids and liquids), chest pain during swallowing, food regurgitation, and nocturnal cough.

Medical history of this case shows that the patient considered herself ill since she was 23 years of age, when she noticed for 1st time symptoms of dysphagia which disturbed her at least once in 2 mo, and these symptoms continued until she was 31-year-old when her episodes of dysphagia became more frequent and occurred once or twice per week. The patient underwent contrast-enhanced X-ray examination of the esophagus (which revealed: stricture of cardiac portion of the esophagus up to 1.5 cm, suprastenotic dilatation of the esophagus up to 4 cm, delayed evacuation of barium meal from the esophagus to the stomach and absence of gastric air bubble). Achalasia cardia was diagnosed. The patient refused to the proposed therapy, as her sense of physical well-being before 2003 was satisfactory, until she developed new complications of pressing pain behind her sternum during meals, regurgitation after meals and nocturnal cough. Since 2012 the patient noted that swallowing of foods (both solids and liquids were difficult at every meal (she reported that the first swallow was difficult but the further swallows were normal) (Table 1).

| Symptom | Score by frequency of symptoms | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| The 58-year-old woman before treatment | Dysphagia to solids | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal |

| Dysphagia to liquids | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Active regurgitation | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Passive regurgitation | None | Occasionally | Daily | After each meal | |

| Spastic chest pain | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Burning chest pain | None | Occasionally | Daily | After each meal | |

| Weight loss, kg | None | < 5 | 5-10 | > 10 | |

| Nocturnal cough | None | Monthly | Weekly | Each night | |

| Nocturnal dyspnea | None | Monthly | Weekly | Each night | |

| Hiccup | None | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

| The 58-year-old woman in 2 mo after treatment | Dysphagia to solids | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal |

| Dysphagia to liquids | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Active regurgitation | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Passive regurgitation | None | Occasionally | Daily | After each meal | |

| Spastic chest pain | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Burning chest pain | None | Occasionally | Daily | After each meal | |

| Weightoss, kg | None | < 5 | 5-10 | > 10 | |

| Nocturnal cough | None | Monthly | Weekly | Each night | |

| Nocturnal dyspnea | None | Monthly | Weekly | Each night | |

| Hiccup | None | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

| The 79-year-old woman | Dysphagia to solids | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal |

| Dysphagia to liquids | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Active regurgitation | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Passive regurgitation | None | Occasionally | Daily | After each meal | |

| Spastic chest pain | None | Occasionally | Daily | Each meal | |

| Burning chest pain | None | Occasionally | Daily | After each meal | |

| Weight loss, kg | None | < 5 | 5-10 | > 10 | |

| Nocturnal cough | None | Monthly | Weekly | Each night | |

| Nocturnal dyspnea | None | Monthly | Weekly | Each night | |

| Hiccup | None | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | |

General performance status was rather satisfactory at the time of admission to the hospital. Body mass index was 30.4 kg/m2 (class I obesity). Skin and visible mucosa were normal. Breathing was harsh above the lungs; no abnormal breath sounds were heard. Heart sounds were rhythmic and muffled. Heart rate was 70 beats per minute. Arterial blood pressure was 130/70 mmHg. Palpation revealed that abdomen was soft and painless in all areas. Liver could be palpated at the edge of the right costal arch. Costovertebral angle tenderness was negative at both sides.

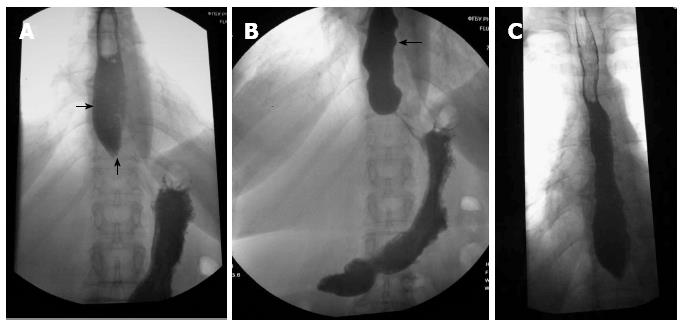

Diagnostic findings: complete blood count - hemoglobin 138 g/L, erythrocytes 4.3 × 1012, leukocytes 4.5 × 109, platelets 269.2 × 109, ESR 5 mm/h. Blood biochemistry: total protein 8.0 g/dL, albumin 4.2 g/dL, creatinine 1.0 mg/dL. Clinical urine analysis showed that all findings were within normal range. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed that the patient’s esophagus had very elastic walls and the esophageal lumen was enlarged up to 4 cm. There were foamy mucus in the lumen, esophageal mucosa was hyperemic in the lower third and had grayish-pearl color tone. The cardiac region was closed. Moderate amount of bile was found in the stomach, folds of mucosa were high and longitudinally-wavy. Stomach mucosa was thin and was hyperemic in the antrum region. Contrast-enhanced X-ray examination of the esophagus: barium meal test revealed that the act of swallowing was not impaired, fluid level was determined during the fasting state in Th8 projection. Width of the esophagus was 4 cm and the outlet of the esophagus was 0.8 cm (Figure 1A). Tertiary contractions of esophageal wall were observed (Figure 1В). The esophagus periodically emptied with small portions. 2/3 of contrast materials were detected in the esophagus 20 minutes after the start of examination (Figure 1С).

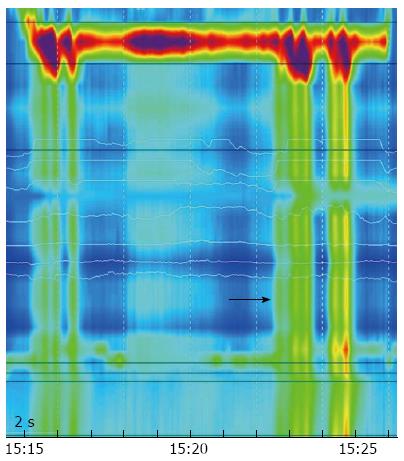

According to the findings of high resolution manometry, the following deserved high attention: Resting Pressure of lower esophageal sphincter was 37 mmHg, Integrated Relaxation Pressure was 20 mmHg and there was absence of normal peristaltic contractions of the esophagus in response to wet swallows (Figure 2).

Course of the treatment with spasmolytics and antacids was performed in the clinic as the first stage of treatment. In view of II type of achalasia cardia, 3 sessions of pneumatic dilatation of the cardia were performed at the second stage of treatment using balloon with a diameter of 3.5 cm. Pressure was built up to 140-230 mmHg, procedure lasted for about 60 s. The patient underwent the procedure satisfactorily without any complications. The patient’s state of physical well-being improved after dilatation of the cardia: dysphagia after ingestion of solids and liquids was resolved, and there were no passive and active regurgitation, no chest pain and episodes of nocturnal cough reduced to once per week.

Two months after the above conducted treatment, the patient’s complaints were assessed again (Table 1) and the sum of scores reduced from 14 to 3 which indicated the success of the conducted treatment.

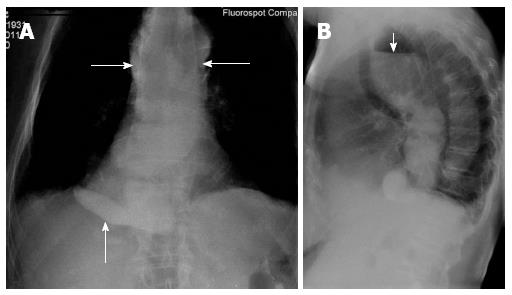

The patient’s mother, (Patient P) an 81-year-old, also suffers from achalasia cardia. History of her disease: patient was diagnosed with a congenital elongation of the esophagus during her childhood. Since the age of 25 she noted dysphagia after ingestion of solid food which occurred very rarely, at least once or twice per month. Since the age of 55, the patient noted episodes of chest pain upon swallowing. Since the age of 78, the patient noted a significant worsening in her state of physical well-being which included difficulty in swallowing at every meal, and also vomiting of food which had just been ingested. The patient underwent X-ray examination of the esophagus which revealed that there was a marked dilatation of the lower third of the esophagus up to 10 cm, rough deformation with multiple cascade folds, and she was diagnosed with achalasia cardia. However the patient was not proposed to undergo treatment regarding her old age and her state of physical well-being continued to worsen with occurrence of dysphagia after ingestion of liquid food in addition to the above mentioned complaints. The patient lost almost 15 kg during 1 year (Table 1). And she was urgently hospitalized in inpatient surgical department where she was examined and esophagogastroduodenoscopy findings revealed: stricture of the lower third of the esophagus up to 1/3 of the lumen, atrophic gastritis with hemorrhagic component. X-ray examination revealed significant dilatation of the esophagus up to 11 cm and rough deformations with multiple cascade folds (Figure 3A and B).

Patient underwent surgery in 2011 which involved the placement of a stent through constricted esophagus in the stomach, however it proved to be ineffective as the patient still had vomiting of just ingested food and impaired movement of liquid food through the esophagus during the postoperative period, So within a week gastrostomy was performed on the patient and the patient received nutrition through the G-tube.

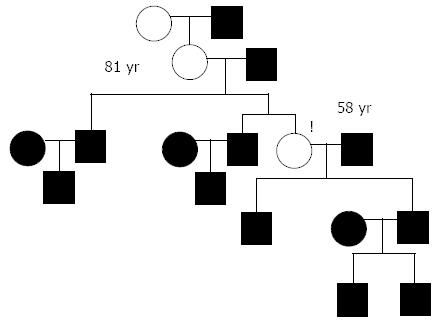

This case report represents vertical inheritance of achalasia cardia (Figure 4). An interview revealed that our patient’s grandmother had suffered for 20 years from dysphagia until her death at the age of 60 due to stroke and no examination of esophagus was performed on her.

It is to be noted that this disease manifested with dysphagia at a rather early age of 23-25 both in the woman and her daughter and presented with entire clinical symptoms like dysphagia, passive and active regurgitation, chest pain which developed just after many years. Also it is necessary to notice that both the patients had nocturnal coughs, and the woman had nocturnal dyspnea which indicated the state of decompensation of achalasia cardia and absolute need for therapy.

Method of treatment for achalasia cardia of the patient’s mother is of great interest, especially the placement of stent through constricted esophagus in the stomach that is usually used as a palliative method of treatment of esophageal tumors. This explains unfavourable postoperative period with persisted dysphagia and vomiting as the placed stent prevents the lower esophageal sphincter from opening. In view of long-lasting disease and rough deformation of the esophagus the patient was subjected to gastrostomy to allow nutrition, at present she still lives with gastrostome. This surgery severely affected patient’s social life and caused a persistent inflammation of skin around the gastrostome.

As of genetic theory, first of all genetic syndromes seen in pediatric practice and associated with the development of achalasia cardia should be mentioned. Mutation of ALADIN 12q13 gene is the most common cause of achalasia cardia in children, it leads to the development of autosomal-recessive disease, so called All grove syndrome or ААА syndrome which is characterized by the development of achalasia, alacrimia and Addison’s disease[4].

Risk of achalasia is also increased in children with Down’s syndrome. Approximately 75% of children with trisomy 21 have gastrointestinal diseases and 2% develop achalasia[5]. Risk of achalasia in children with Down’s syndrome is 200 time higher than in normal population[6]. Besides Down’s syndrome, incidence of achalasia cardia is significantly higher in children with Rozycki syndrome and Pierre-Robin syndrome.

Speaking about the adult population, polymorphism of some genes is by all means important in the development of achalasia cardia. It is proved that by the theory of polymorphism of IL23R gene localized on chromosome Ip31. It is also supported by the study on IL23R Arg381 Gln gene polymorphism in 262 patient with achalasia and 802 healthy volunteers which was done in Spain. Results have also revealed that this gene polymorphism had occurred in men who had suffered from achalasia (less than 40 years of age), which allows us to conclude that IL23R is very important as a predisposing factor in the development of idiopathic achalasia cardia[7].

IL10 promoter haplotype GCC was associated with the development of idiopathic achalasia cardia in patients of the same Spanish population[8].

In addition, a link was found between achalasia cardia and specific HLA-genotype. Study conducted in 2002 had investigated the level of circulating autoantibodies and HLA DQA1 and DQB1 alleles in patients with achalasia and healthy volunteers and demonstrated that autoantibodies to Auerbach’s plexus were revealed in all women and 66.7% of men with idiopathic achalasia and DQA1 × 0103 and DQB1 × 0603-alleles[9].

It’s also important to note the theory of polymorphism of NO-synthase (NOS) which is a fragment catalyzing the production of nitrogen oxide from arginine, oxygen and NADPH. There are 3 different types of NOS: neuronal (nNOS), inducible (iNOS) and endothelial (eNOS). Their responsible genes were located on chromosomes: 12q24.2, 17q11.2-q12 and 7q36. Some works have reported polymorphism of all 3 genes in patients with achalasia. Of these, the polymorphism of iNOS22 × A/Ab and eNOS × 4a4a were those which were most frequently detected[10,11].

Besides nitrogen oxide, vasoactive intestinal peptide is the second neurotransmitter of inhibitory neurons. One of its receptors, Receptor 1 which belongs to the secretin family, is expressed by immune cells such as T- lymphocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells[12]. Polymorphism of this gene (VIPR1) can also play an important role in the development of idiopathic achalasia. VIPR1 gene is localized on chromosome 3p22 and some studies have reported five simple nucleotide polymorphisms of this gene such as (rs421558) Intron-1, (rs437876) Intron-4, (rs417387) Intron-6, rs896 and rs9677 (3’UTR)[13].

Genes responsible for the synthesis of protein tyrosine phosphatase, nonreceptor type 22 (PTPN22) are localized in chromosome 1p13.м3-p13 and is associated with the development of autoimmune diseases[14]. Lymphoid-specific phosphatase (Lyp), one of the phosphatases that are coded by this gene, is an intracellular tyrosine phosphatase which is an important regulator of T-cell activation[15]. С1858T polymorphism of PTPN22 gene (when codon 620 Arg (R) is replaced by Trp (W) resulting in production of Lyp-W620 instead of Lyp-R620 that leads to an increase in T-lymphocyte activity) is an important risk factor for the development of autoimmune disease[16,17]. The study conducted in Spain also revealed that the polymorphism described above increased the risk of achalasia in Spanish population[18].

In conclusion it should be noted that this case report illustrates the genetic theory of development of achalasia cardia. Genetic analysis which is currently widely performed in patients with achalasia helped a lot to answer to the question regarding etiology of this disease, however there is need for more intensive study in this field.

P- Reviewers: Jani K, Schuchert MJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Spechler SJ. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of achalasia. Uptodate. [Internet] 2010 [cited 2011 April 19]. Available from: http: //www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-ofachalasia. |

| 3. | Willis T. Pharmaceutice ratioalis sive diatribe de medicamentarum operationibus in humano corpore. London: Hagia Comitis 1674; . |

| 4. | Tullio-Pelet A, Salomon R, Hadj-Rabia S, Mugnier C, de Laet MH, Chaouachi B, Bakiri F, Brottier P, Cattolico L, Penet C. Mutant WD-repeat protein in triple-A syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;26:332-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moore SW. Down syndrome and the enteric nervous system. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:873-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zárate N, Mearin F, Gil-Vernet JM, Camarasa F, Malagelada JR. Achalasia and Down’s syndrome: coincidental association or something else? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1674-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Emami MH, Raisi M, Amini J, Daghaghzadeh H. Achalasia and thyroid disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:594-599. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nuñez C, García-González MA, Santiago JL, Benito MS, Mearín F, de la Concha EG, de la Serna JP, de León AR, Urcelay E, Vigo AG. Association of IL10 promoter polymorphisms with idiopathic achalasia. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:749-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ruiz-de-León A, Mendoza J, Sevilla-Mantilla C, Fernández AM, Pérez-de-la-Serna J, Gónzalez VA, Rey E, Figueredo A, Díaz-Rubio M, De-la-Concha EG. Myenteric antiplexus antibodies and class II HLA in achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:15-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vigo AG, Martínez A, de la Concha EG, Urcelay E, Ruiz de León A. Suggested association of NOS2A polymorphism in idiopathic achalasia: no evidence in a large case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1326-1327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mearin F, García-González MA, Strunk M, Zárate N, Malagelada JR, Lanas A. Association between achalasia and nitric oxide synthase gene polymorphisms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1979-1984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Paladini F, Cocco E, Cauli A, Cascino I, Vacca A, Belfiore F, Fiorillo MT, Mathieu A, Sorrentino R. A functional polymorphism of the vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 gene correlates with the presence of HLA-B*2705 in Sardinia. Genes Immun. 2008;9:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Paladini F, Cocco E, Cascino I, Belfiore F, Badiali D, Piretta L, Alghisi F, Anzini F, Fiorillo MT, Corazziari E. Age-dependent association of idiopathic achalasia with vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1 gene. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:597-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de León AR, de la Serna JP, Santiago JL, Sevilla C, Fernández-Arquero M, de la Concha EG, Nuñez C, Urcelay E, Vigo AG. Association between idiopathic achalasia and IL23R gene. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:734-738, e218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jawaheer D, Seldin MF, Amos CI, Chen WV, Shigeta R, Etzel C, Damle A, Xiao X, Chen D, Lum RF. Screening the genome for rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility genes: a replication study and combined analysis of 512 multicase families. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:906-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Oene M, Wintle RF, Liu X, Yazdanpanah M, Gu X, Newman B, Kwan A, Johnson B, Owen J, Greer W. Association of the lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase R620W variant with rheumatoid arthritis, but not Crohn’s disease, in Canadian populations. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1993-1998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ghoshal UC, Daschakraborty SB, Singh R. Pathogenesis of achalasia cardia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3050-3057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Santiago JL, Martínez A, Benito MS, Ruiz de León A, Mendoza JL, Fernández-Arquero M, Figueredo MA, de la Concha EG, Urcelay E. Gender-specific association of the PTPN22 C1858T polymorphism with achalasia. Hum Immunol. 2007;68:867-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |