CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old woman with chronic Hepatitis B carrier state initially presented with abdominal pain associated with cholelithiasis in 2005. At the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy extensive portal vein thrombosis was noted. Evaluation revealed a myeloproliferative disorder with a gain of function point mutation (V617F) of the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) signaling protein. She was treated with warfarin for less than 1 year and was subsequently lost to follow up. She was not treated with beta blockers for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. In 2008, she presented with transient diffuse abdominal pain and fever. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen revealed splenomegaly (16.3 cm) with cavernous transformation of the portal vein and marked gastric, esophageal, mesenteric, and splenic varices. She was again lost to follow up prior to treatment for portal hypertension.

The patient was asymptomatic for the next 2 years until May 2010 when she presented to our hospital with hematemesis. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for normal liver tests, hemoglobin level of 9.6 g/dL, white blood cell count of 8.2 × 109/L, and platelet count of 398 × 109/L. Hepatitis B carrier state was confirmed with positive hepatitis B surface antigen, negative surface antibody, and undetectable hepatitis B DNA. Upper endoscopy revealed non-bleeding, moderate to large sized varices in the lower esophagus and large gastric varices, one of which had an ulcer with an associated fibrin plug and adherent clot. Abdominal MRI again showed cavernous transformation at the porta-hepatis with occlusion of the main portal and splenic veins. The spleen measured 18 cm, and there were multiple mesenteric, gastric, esophageal and splenorenal varices (Figure 1). The liver had a normal radiographic appearance. Visualization of the gastric varices and spleno-renal shunt for direct embolization was unsuccessful, and the patient was discharged on daily nadolol for secondary variceal bleeding prophylaxis with an achieved heart rate of 65 beats per minute. The patient expressed great anxiety about the potential for re-bleeding and opted for PSE after a careful discussion of the potential risks. She was not a candidate for BRTO without a patent spleno-renal shunt or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) due to extensive portal vein thrombosis. Cyanoacrylate glue was not available in our center. Elective PSE to limit venous inflow into the portal circulation was performed with micro-catheter injection of 100-500 micron microspheres at the hilar aspect of the splenic artery. Completion splenic angiogram demonstrated embolization of 30%-40% of the splenic parenchyma with sparing of the superior and inferior portions of the spleen (Figure 2). The patient was discharged on a course of moxifloxacin and metronidazole.

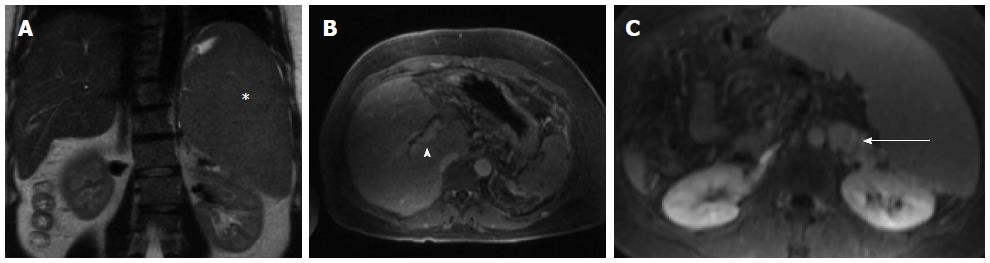

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging - abdomen from two months prior to embolization.

Massive splenomegaly is shown (A, asterisk) with associated cavernous transformation of the portal vein (B, arrow head) and large splenorenal varices (C, arrow).

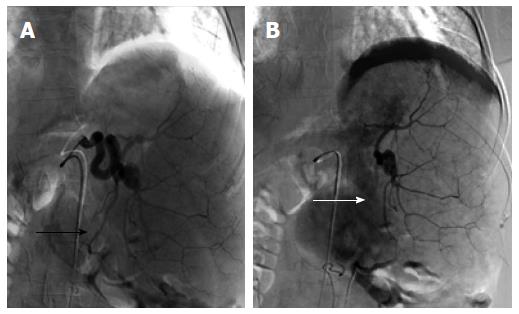

Figure 2 Splenic artery embolization with a single, inferomedial branch targeted to achieve 30%-40% of splenic parenchymal embolization.

The pre-embolization blood supply to this vascular territory (A, black arrow) is significantly reduced following the embolization (B, white arrow), with reactive hyperemia of the medial aspect of the spleen.

Five days following the procedure, the patient presented with severe abdominal pain and distention associated with new onset ascites and left upper abdominal tenderness. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for a white blood cell count of 25 × 109/L with 82% neutrophils, and a platelet count of 1061 × 109/L. International normalized ratio was 1.4. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast revealed splenomegaly with extensive infarction and non-enhancement of most of the spleen with only a small focus of enhancing splenic parenchyma (Figure 3). Diagnostic paracentesis revealed a white blood cell count of 4.8 × 109/L with 71% neutrophils, protein 3.4 g/dL, and albumin 1.4 g/dL. Intravenous cefotaxime was administered. The white blood cell count and platelet count progressively rose to 36 × 109/L and 1600 × 109/L, respectively. Cultures of both blood and ascitic fluid remained negative. Aspirin, unfractionated heparin, hydroxyurea 1000 mg twice daily were administered, and three cycles of platelet-pheresis were performed. The white blood cell and platelet count progressively decreased to within normal limits during the hospitalization over 1 wk. The abdominal pain and distention improved, and she was discharged on aspirin, warfarin, and hydroxyurea.

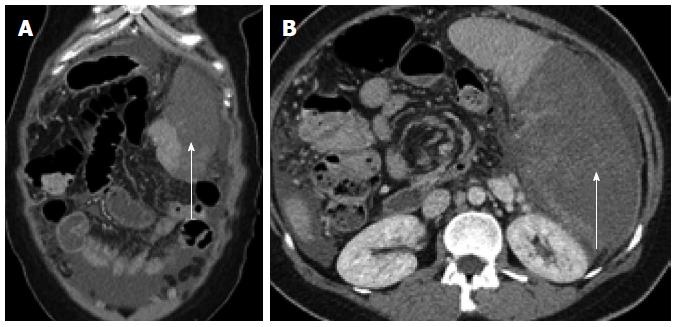

Figure 3 Five days following embolization the patient presented with symptoms of post-embolization syndrome and extensive splenic infarction, markedly exceeding that expected by the targeted vascular territory.

Arrows demonstrate significant volume of non-enhancing spleen in both coronal (A) and axial (B) images

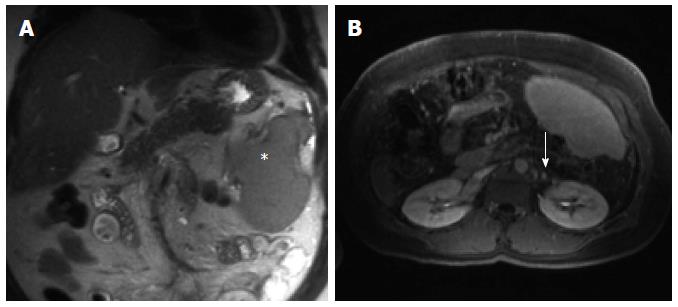

The patient remains asymptomatic, without recurrent bleeding 3 years following PSE. Abdominal MRI in September 2012 revealed persistent cavernous transformation of the portal vein, stable splenic infarction limited to the superior and posterior portions of the spleen, and markedly reduced burden of splanchnic varices (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging 3 years post partial splenic embolization shows a significantly reduced splenic volume (A, asterisk) with partial recuperation of the previously embolized parenchyma (B) and near complete resolution of the peri-renal varices, confirming reduced variceal and portal venous pressures (B, arrow).

DISCUSSION

Approximately 40% of cases of non-cirrhotic portal vein thrombosis (PVT) are related to an underlying myeloproliferative disorder, including essential thrombocytosis, polycythemia vera, and primary myelofibrosis[1]. The JAK2 tyrosine kinase mutation has been found in 20%-40% of patients with splanchnic venous thrombosis[2-6]. The clinical presentation of PVT associated with the JAK2 mutation can be either acute or chronic. Although patients may present with acute thrombosis and abdominal pain, fever, and other signs of bowel ischemia resulting from splanchnic venous congestion, patients typically present with long-standing complications from portal hypertension due to portal and splanchnic venous thrombosis with gastro-esophageal variceal bleeding and ascites[6]. Varices in cirrhosis develop as a manifestation of portal hypertension due to both increases in intrahepatic resistance limiting portal blood flow, and increased splanchnic blood flow from mesenteric arterial vasodilatation. Importantly, in patients with MPD and portal and splanchnic venous thrombosis increased splenic blood flow associated with marked splenomegaly coupled with high resistance and limitation of venous outflow is an important driving force to the development of gastric varices.

Treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in the presence of PVT is frequently problematic. Pharmacologic options include somatostatin and its analogue octreotide and non-selective beta-blockers. Somatostatin is not appropriate for long-term therapy owing to its short half-life and tachyphylaxis. The non-selective beta blockers alone are often inadequate to prevent rebleeding, with rates as high as 55% at 26 mo[7]. Sclerotherapy and band ligation are not effective due to the high risk of early rebleeding. Although endoscopic treatment with cyanoacrylate glue reduces rates of gastric variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients by as much as 40% compared to beta blockers alone[7], it is not widely available in the United States, and the technique has not been extensively studied in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension from thrombotic disorders. The re-bleeding rates in patients treated with cyanoacrylate glue are high, in some series occurring in over 50% of patients[8]. Finally, placement of a TIPS frequently is not possible in patients with cavernous transformation and extensive thrombosis[9]. As in our case, it may not always be possible to access the varices of concern with balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) in which the presence of a spontaneous splenorenal shunt is utilized to gain access to the gastroesophageal variceal complex via the left renal vein[10]. In addition, BRTO has been shown to exacerbate esophageal varices[11].

Obstruction to portal inflow resulting from either pre-hepatic causes as in PVT or in cirrhosis leads to splenic hyperplasia, splenomegaly, and a resultant increase in the splenic contribution to portal blood flow[12-13]. PSE aims to reduce venous inflow into the portal vein, and in this manner decreases portal venous pressure. PSE has been shown to reduce both splenic and portal vein pressures in patients with gastroesophageal varices and splenomegaly[14], and it has been used to successfully treat thrombocytopenia and esophageal varices either alone or in combination with BRTO and band ligation[15-18].

Following the procedure, our patient developed “post-embolization syndrome”. This syndrome is a common side effect of any solid organ embolization and includes abdominal pain, fever and vomiting. Importantly, greater than 70% infarction is associated with longer symptom duration and higher complication rates, especially splenic abscess formation[18]. We speculate that reduced hypersplenism further unmasked the underlying thrombocytosis related to the MPD which led to a self-perpetuating process of excessive splenic auto-infarction. This phenomenon is similar to the unmasking of latent essential thrombocytosis that has been described in a patient undergoing splenectomy to control variceal bleeding in the presence of a large mesenteric clot burden[19]. A subsequent decrease in splenic blood flow led to a remarkable reduction in portal pressure as demonstrated by the nearly complete resolution of gastric variceal burden.

There are currently no published guidelines for the management of gastric varices in the presence of extensive portal and splanchnic thrombosis in MPD in which TIPS or BRTO are not possible. Our case demonstrates that partial splenic embolization can be an effective strategy in this otherwise difficult clinical scenario. Unmasking of an underlying thrombocytosis and “post-embolization syndrome” should be anticipated with measures taken to limit the extent of embolization, considering pre-procedure hydroxyurea, and to closely monitor for and rapidly treat the ensuing thrombocytosis with platelet-pheresis if necessary[20].