Published online Oct 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.14076

Revised: April 29, 2014

Accepted: June 21, 2014

Published online: October 14, 2014

Processing time: 223 Days and 18 Hours

The small intestine is approximately 5-6 m long and occupies a large area in the abdominal cavity. These factors preclude the use of ordinary endoscopy and X-ray to thoroughly examine the small intestine for bleeding of vascular malformations. Thus, the diagnosis of intestinal bleeding is very difficult. A 47-year-old man presented at the hospital 5 mo ago with dark stool. Several angiomas were detected by oral approach enteroscopy, but no active bleeding was observed. Additionally, no lesions were detected by anal approach enteroscopy; however, gastrointestinal tract bleeding still occurred for an unknown reason. We performed an abdominal vascular enhanced computed tomography examination and detected ileal vascular malformations. Ileum angioma and vascular malformation were detected by a laparoscopic approach, and segmental resection was performed for both lesions, which were confirmed by pathological diagnosis. This report systemically emphasizes the imaging findings of small intestinal vascular malformation bleeding.

Core tip: A 47-year-old man presented at the hospital 5 mo ago with dark stool. Several angiomas were detected by oral approach enteroscopy, but no active bleeding was observed. Additionally, no lesion was detected by anal approach enteroscopy; however, gastrointestinal tract bleeding occurred for an unknown reason. Ileal vascular malformation was detected by abdominal vascular enhanced computed tomography, and ileal angioma and vascular malformation were detected by a laparoscopic approach. Segmental resection was performed for both lesions, which were confirmed by pathological diagnosis. This report systemically emphasizes the imaging findings of small intestinal vascular malformation bleeding.

- Citation: Cui J, Huang LY, Lin SJ, Yi LZ, Wu CR, Zhang B. Small intestinal vascular malformation bleeding: A case report with imaging findings. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(38): 14076-14078

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i38/14076.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.14076

Generally, the first sign of small intestinal disease is bleeding, the small intestine is about several meters long. These factors preclude the use of ordinary endoscopy and X-ray to thoroughly examine the small intestine[1]. Electronic enteroscopy can be used to examine the small intestine[2]. However, in some patients, bleeding of small intestinal lesions cannot be detected by enteroscopy because oral and anal approach enteroscopy do not reach a “blind region” from either side. Thus, a bleeding site in the “blind region” cannot be detected by enteroscopy, especially for cases of bleeding caused by vascular malformation. Generally, diagnoses of bleeding in the “blind region” requires angiography, but angiography has the drawbacks of causing trauma, having a long time of duration and costing large amounts[3].

Here, we report a case of bleeding at a small intestinal vascular malformation with an emphasis on the imaging findings obtained by small intestinal endoscopy, abdominal vascular contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), laparoscopy and pathology.

A 47-year-old man, presented at the hospital 5 mo ago with dark stool. The patient was anemic, with a hemoglobin level of 73 g/L. Several angiomas were detected by oral approach enteroscopy without active bleeding site detected. Additionally, no bleeding site was observed by anal approach enteroscopy; however, gastrointestinal tract bleeding still occurred for an unknown reason. Next, we performed an abdominal vascular enhanced CT examination. After CT scanning, reconstruction for CT images was performed.

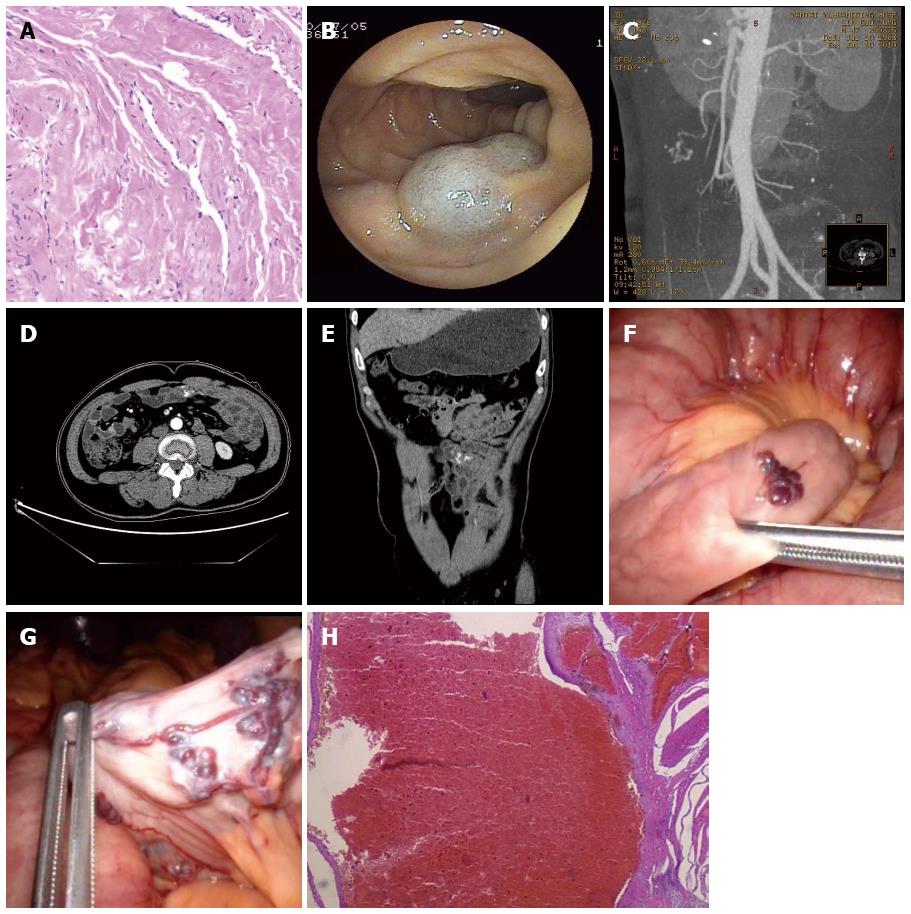

Ileal vascular malformation was detected by abdominal vascular enhanced CT, and ileal angioma and vascular malformation were detected by a laparoscopic procedure. Segmental resection was done for both lesions, which were confirmed by pathological diagnosis (Figure 1).

Small intestinal bleeding, which includes bleeding lesions located at any site from the Treitz ligament to the ileocecal junction, is known to occur for the following reasons: duodenal ulcer, inflammatory bowel disease or small intestinal vascular malformation or tumor[4]. Among these conditions, vascular malformation, tumor and inflammatory bowel disease are the most common causes of bleeding. Because the small intestine is difficult to reach by gastroscope, duodenoscope or colonoscope, ordinary diagnostic methods have limitations for small intestinal examinations and, therefore, small intestinal bleeding is difficult to diagnose[5].

Arteriography is useful for small intestine bleeding, however, according to previous reports, when extravasation of contrast media can be detected by X-ray, it means that the bleeding rate is more than 0.5 mL/min. Therefore, angiography is useful for the diagnosis of active gastrointestinal tract bleeding[6]. However, arteriography can cause trauma, and it is only useful for vascular diseases or tumors with a rich blood supply.

When gastrointestinal tract bleeding cannot be controlled by non-surgical measures, exploratory laparotomy becomes necessary. Because the cause of bleeding is unclear, exploratory laparotomy can fail or the lesion might not be properly treated and, therefore, the postoperative re-bleeding rate is high. Recently, small intestinal bleeding has been diagnosed by enteroscopy, but not all bleeding sites could be detected[7,8]. Diagnosis often fails because enteroscopy through both the mouth and anus does not cover the entire gastrointestinal tract. With image re-construction function of enhanced CT, CT angiography has replaced ordinary angiography for the diagnosis of vascular malformation[9,10]. For the patient described in this case report, vascular malformation was diagnosed by abdominal enhanced CT, while the malformation was not observed by enteroscopy. Therefore, for patients with small intestinal bleeding, we recommend that abdominal vascular enhanced CT should be conducted before a surgical operation to avoid missing other vascular malformations. We suggest this approach regardless of whether the bleeding sites can be detected by enteroscopy.

We reported a patient with cavernous angioma on the right knee. Several years later, small intestinal angioma and vascular malformation was detected by double-balloon enteroscopy and CT, indicating that he had multiple angiomas.

A 47-year-old man presented at hospital with dark stool.

The patient was anemic.

Peptic ulcer, colon cancer, small intestinal tumor.

Hemoglobin was 73 g/L.

Ileal vascular malformation was detected by abdominal vascular enhanced computed tomography (CT).

Small intestinal vascular malformation.

Segmental resection was performed for the small intestinal angioma and vascular malformation by a laparoscopic approach.

The small intestine was difficult to reach using a gastroscope, duodenoscope or colonoscope. Therefore, these ordinary diagnostic methods were difficult to diagnose small intestine disease.

Abdominal vascular contrast-enhanced CT indicates that contrast media was injected through a peripheral vein. CT scanning indicates that CT images were obtained and refined by post-processing; the best images were selected for analysis and diagnosis.

This paper shows that abdominal vascular enhanced CT has a practical value for the diagnosis of small intestinal vascular malformations. This approach can offest the shortcomings of double-balloon enteroscopy, and is especially useful for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

This is a case report of a patient with bleeding of a small intestinal vascular malformation with imaging findings. It is quite nice.

P- Reviewer: Gao BL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Du P

| 1. | Park MS, Lee BJ, Gu DH, Pyo JH, Kim KJ, Lee YH, Joo MK, Park JJ, Kim JS, Bak YT. Ileal polypoid lymphangiectasia bleeding diagnosed and treated by double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8440-8444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Gurkan OE, Karakan T, Dogan I, Dalgic B, Unal S. Comparison of double balloon enteroscopy in adults and children. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4726-4731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | García-Blázquez V, Vicente-Bártulos A, Olavarria-Delgado A, Plana MN, van der Winden D, Zamora J. Accuracy of CT angiography in the diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal bleeding: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1181-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | He Q, Bai Y, Zhi FC, Gong W, Gu HX, Xu ZM, Cai JQ, Pan DS, Jiang B. Double-balloon enteroscopy for mesenchymal tumors of small bowel: nine years’ experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1820-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bollinger E, Raines D, Saitta P. Distribution of bleeding gastrointestinal angioectasias in a Western population. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6235-6239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dye CE, Gaffney RR, Dykes TM, Moyer MT. Endoscopic and radiographic evaluation of the small bowel in 2012. Am J Med. 2012;125:1228.e1-1228.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Onal IK, Akdogan M, Arhan M, Yalinkilic ZM, Cicek B, Kacar S, Kurt M, Ibis M, Ozin YO, Sayilir A. Double balloon enteroscopy: a 3-year experience at a tertiary care center. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1851-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Willison KR, Hynes G, Davies P, Goldsborough A, Lewis VA. Expression of three t-complex genes, Tcp-1, D17Leh117c3, and D17Leh66, in purified murine spermatogenic cell populations. Genet Res. 1990;56:193-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huprich JE, Barlow JM, Hansel SL, Alexander JA, Fidler JL. Multiphase CT enterography evaluation of small-bowel vascular lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:65-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Masselli G, Gualdi G. CT and MR enterography in evaluating small bowel diseases: when to use which modality? Abdom Imaging. 2013;38:249-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |