Published online Oct 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13999

Revised: January 15, 2014

Accepted: May 29, 2014

Published online: October 14, 2014

Processing time: 232 Days and 12.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the influence of thiopurines and biological drugs on the presence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) in patients with inactive Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: This was a prospective study in patients with CD in remission and without corticosteroid treatment, included consecutively from 2004 to 2010. SIBO was investigated using the hydrogen glucose breath test.

RESULTS: One hundred and seven patients with CD in remission were included. Almost 58% of patients used maintenance immunosuppressant therapy and 19.6% used biological therapy. The prevalence of SIBO was 16.8%. No association was observed between SIBO and the use of thiopurine Immunosuppressant (12/62 patients), administration of biological drugs (2/21 patients), or with double treatment with an anti-tumor necrosis factor drugs plus thiopurine (1/13 patients). Half of the patients had symptoms that were suggestive of SIBO, though meteorism was the only symptom that was significantly associated with the presence of SIBO on univariate analysis (P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis revealed that the presence of meteorism and a fistulizing pattern were associated with the presence of SIBO (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Immunosuppressants and/or biological drugs do not induce SIBO in inactive CD. Fistulizing disease pattern and meteorism are associated with SIBO.

Core tip: Thiopurine Immunosuppressants and biological drugs used in Crohn’s disease are not free from side effects, such as acquiring infections. Our study demonstrated no association between drug treatment and bacterial overgrowth. These results may be explained as the treatment promoting better disease control.

- Citation: Sánchez-Montes C, Ortiz V, Bastida G, Rodríguez E, Yago M, Beltrán B, Aguas M, Iborra M, Garrigues V, Ponce J, Nos P. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in inactive Crohn’s disease: Influence of thiopurine and biological treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(38): 13999-14003

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i38/13999.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13999

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is an imbalance in intestinal microflora, which can show a wide clinical spectrum ranging from mild and unspecific intestinal symptoms, to a severe malabsorption syndrome. A jejunal aspirate culture is considered the gold standard diagnostic test for SIBO; however, the hydrogen glucose breath test (HGBT) and lactulose breath test are currently used in clinical practice. Among them, HGBT seems to have a higher diagnostic accuracy in studies comparing breath tests vs culture[1-3].

Crohn’s disease (CD) involves intestinal changes that in some situations may lead to stasis of intestinal contents and, consequently, SIBO. Included among these changes are intestinal stenosis and dilation, changes in motility, fistulas, or changes caused by surgical treatment of the disease. Several studies have evaluated the overall presence of SIBO to be between 18% and 30%[4-7] in patients with CD.

In the last decade, there have been significant changes in the therapeutic approach to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which have been spurred on by the growing use of immunosuppressant agents (specially azathioprine) and the use of biological drugs, such as anti-tumor necrosis factor agents (anti-TNF: infliximab or adalimumab). Incorporation of these drugs in the therapeutic arsenal has improved the results of medical treatment in IBD, especially in CD. Nevertheless, they are not exempt from side effects. Included among these is the increased risk of contracting infections[8-10]. However, it is not known if these patients have an increased prevalence of SIBO.

The primary objective of our study was to determine the influence of thiopurine immunosuppressant and biological treatment with anti-TNF drugs on the presence of SIBO in patients with CD. The secondary objectives were: (1) to study other factors that may be associated with the presence of SIBO; (2) to evaluate the association between the presence of SIBO and the presence of symptoms compatible with SIBO in patients with CD; and (3) to investigate the prevalence of SIBO in our area in patients with inactive CD.

This was a prospective study of patients that were treated for CD in clinical remission in our hospital outpatient appointments and included consecutively from January 2004 to December 2010. Inclusion criteria were: remission [defined as the absence of clinical signs of biological activity -C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fibrinogen, leukocytes, platelets-, with a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) less than 150 points], patients were not on corticosteroid treatment and were over 18 years of age. Exclusion criteria: pregnancy and refusal to participate in the study.

With the patient fasting for at least 10 h after a carbohydrate-free dinner and without smoking since at least the night before, the amount of hydrogen in exhaled air was determined (Quintron model 121; Milwaukee, WI, United States) at baseline and every 30 min for 3 h after ingesting 50 g of glucose in 250 mL of water. The test was considered positive if there was an increase above baseline in hydrogen in the exhaled air greater than 12 ppm on two consecutive measurements. Patients should not have taken antibiotic drugs within the previous month[11-15].

The epidemiological variables collected were gender, age, and body mass index. The disease-associated variables studied were the time of disease progression, the disease location and pattern (Montreal classification)[16], pharmacological treatment (thiopurine immunosuppressant and anti-TNF biologic drugs: infliximab or adalimumab), and surgical treatment (ileocecal valve resection).

The presence or absence of the symptoms compatible with SIBO (bowel frequency, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, meteorism and borborygmus) was evaluated using a structured clinical questionnaire during the clinical interview. This information was absent from five patients.

Variables are reported as absolute frequencies, as percentages for qualitative data, and as mean ± SD for continuous variables. Univariate analyses were performed using the χ2-test for qualitative variables, or Fisher’s exact test if the conditions for use of the previous test were not met. A Mann-Whitney U-test for independent samples was used, as appropriate, to assess differences between quantitative variables. For all analyses, a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The variables introduced in the multivariate analysis were those that showed statistically significant differences in the univariate analysis and those that have clinical significance. A logistic regression was used to assess the association between the presence of SIBO and several independent variables (see study variables).

The ethical committee (CEIC) of our Hospital approved the study. All patients gave their written consent to undergo the breath test after receiving detailed information on the purpose of the study.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the sample studied. Eighteen of the 107 patients (16.8%) had SIBO. Table 2 shows the association between different independent variables and the presence of SIBO. No association was seen between SIBO and the use of thiopurine immunosuppressants, administration of anti-TNF treatment, or with the double treatment, or PPI.

| Time since disease diagnosis (yr) | 8.5 ± 7.3 |

| Age (yr) | 40.8 ± 12.1 |

| Gender (% female) | 56 (52.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.2 ± 4.9 |

| Location | |

| Ileum | 39 (36.5) |

| Ileum and colon | 53 (49.5) |

| Colon | 15 (14) |

| Pattern | |

| Inflammatory | 29 (27.1) |

| Stenotic | 58 (54.2) |

| Fistulizing | 20 (18.7) |

| Ileocecal valve resection | 63 (58.9) |

| Treatment | |

| Immunosuppressant1 | 62 (57.9) |

| Biological treatment2 | 21 (19.6) |

| Double (immunosuppressant + biological) | 13 (12.1) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 19 (17.8) |

| Bacterial overgrowth | 18 (16.8) |

| Presence of symptoms (n = 102) | 55 (51.4) |

| Bowel frequency (24 h) | 2.8 ± 2 |

| Bacterial overgrowth | P value | ||

| YES 18 (16.8) | NO 89 (83.2) | ||

| Time since disease diagnosis (yr) | 9.5 ± 7.1 | 8.4 ± 7.4 | NS |

| Age (yr) | 47 ± 17.8 | 39.5 ± 10.3 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25 ± 6.2 | 25.2 ± 4.6 | NS |

| Ileal location | 17 (94.4) | 75 (84.3) | NS |

| Pattern | |||

| Inflammatory | 2 (11.1) | 27 (30.3) | NS |

| Stenotic | 10 (55.5) | 48 (53.9) | NS |

| Fistulizing | 6 (33.3) | 14 (15.7) | NS |

| Ileocecal valve resection | 12 (66.6) | 51 (57.3) | NS |

| Treatment | |||

| Immunosuppressant | 12 (66.6) | 50 (56.2) | NS |

| Biological | 2 (11.1) | 19 (21.3) | NS |

| Double (immunosuppressant + biological) | 1 (5.5) | 12 (13.5) | NS |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 4 (22.2) | 15 (16.9) | NS |

| Presence of symptoms | 13 (72.2) | 42 (47.2) | NS |

| Abdominal pain | 6 (33.3) | 36 (40.4) | NS |

| Abdominal distension | 9 (50) | 43 (48.3) | NS |

| Meteorism | 12 (66.6) | 37 (41.6) | < 0.05 |

| Borborygmus | 11 (61.1) | 42 (47.2) | NS |

| Bowel frequency (24 h) | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | NS |

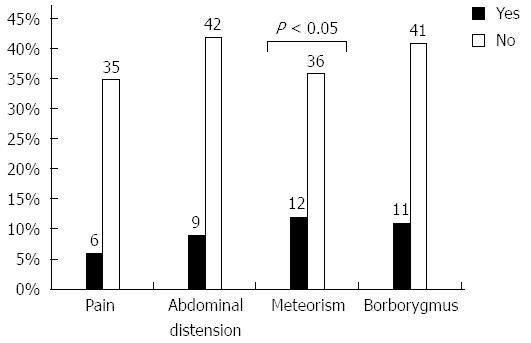

Fifty-one percent of patients reported symptoms compatible with SIBO, which were graded as moderate or intense, though meteorism was the only symptom that was significantly associated with the presence of SIBO on univariate analysis (Figure 1).

On multivariate analysis, that presence of meteorism (P < 0.05) and a fistulizing pattern (P < 0.05) were associated with the presence of SIBO. No association was found with the remaining variables included in the study (Table 3).

| With bacterial overgrowth | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Meteorism | |||

| No | 6/53 (11) | Reference | |

| Yes | 12/49 (24) | 4.1 (1.2-13.6) | < 0.05 |

| Fistulizing pattern | |||

| No | 12/87 (14) | Reference | |

| Yes | 6/20 (30) | 4.2 (1.0-17.5) | < 0.05 |

Thiopurine immunosuppressant and biological drugs (anti-TNF) used in CD are not free from side effects. Included among these is an increased risk of acquiring infections[8-10]. Nevertheless, no studies have evaluated the risk of SIBO in these patients. Thus, our objective was to investigate the prevalence of SIBO in our area in patients with inactive CD, and to determine the influence of thiopurine drugs and anti-TNF on CD, as well as to determine if there is an association between use of immunosuppressant or biological drugs and the presence of SIBO symptoms.

The prevalence of SIBO in our study was 16.8%, which is slightly lower than other published studies (18%-30%)[4-7]. One of these studies[4] included 67 non-selected patients with CD showing a SIBO prevalence of 18% in those patients who had not been surgically treated and 30% in patients who had undergone surgery for CD. An association was found in this study between the presence of SIBO and increased orocecal transit time. Mishkin et al[5] demonstrated a SIBO prevalence of 28% (20 out of 71 patients), which was significantly associated with the presence of stenosis, but not with CDAI. In a later study[6], SIBO was detected in 38 out of 150 patients studied (25.3%), being most frequent in patients who had a greater number of bowel movements, lower weight and with ileum and colonic involvement, partial colectomy, or a history of multiple bowel surgeries. In our study, we found no association between SIBO and the number of bowel movements or with BMI, though we did find a higher percentage of SIBO in patients with CD with ileal involvement compared to patients with ileocecal valve resection. In a previously mentioned study[6], an association was found between the presence of abdominal pain and SIBO. Our patients had symptoms that could be related to SIBO, though meteorism was the only symptom to reach statistical significance, both in the univariate and the multivariate analysis. There are other situations that may lead to similar symptoms in CD patients. Among these are malabsorption of bile salts or situations related to the disease itself, such as stenosis or conditions arising from intestinal resection.

One possible limitation of the study is that endoscopic inactivity was not ruled-out; thus, in some cases the symptoms may be caused by intestinal activity that is not detected with the methods used (CDAI, acute-phase reactants, absence of corticosteroid treatment). Another methodological limitation could be the presence of possible false-negative cases where SIBO is limited to the distal ileum because the glucose is physiologically absorbed within the jejunum.

Immunosuppressant and biological treatment causes changes in immunity with a slightly increased risk of developing infections. These are primarily mild, except in the case of combined treatment of two or three drugs, where the risk of severe opportunistic infections is at least four times greater when the combination includes corticosteroids[8-10]. Our study suggested that patients with CD receiving double therapy do not have a greater risk of developing SIBO. It is important to differentiate between systemic infections in which risk is increased if immunity is altered, and local infection, such as SIBO, in which other factors certainly play a role. Our study does not prove the existence of an association between drug treatment and SIBO. These results may indicate that the better disease control in these patients results from the use of immunosuppressants or biological drugs.

Another interesting finding was that the fistulizing pattern was associated with the presence of SIBO in the multivariate analysis. This data differs from the study by Mishkin et al[5], in which a higher prevalence of SIBO was found in patients with stenosis. In both cases, there were anatomical changes that may justify these findings.

Furthermore, chronic acid suppression and the resultant hypochlorhydria associated with PPI use have been hypothesized to alter the intraluminal environment to promote SIBO. This relationship between PPI remains controversial and confusing[17]. No association was seen between SIBO and the use of PPIs in our study.

In conclusion, treatment with immunosuppressants and/or biological drugs was not associated with bacterial overgrowth in patients with CD in remission. SIBO is more frequent in those patients with a fistulizing disease pattern and seems to be associated with the presence of meteorism.

Diarrhea is a symptom that is a common clinical manifestation in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). There are certain situations capable of inducing diarrhea in these patients, which are not attributable to the inflammatory bowel activity itself; for example, malabsorption of bile salts, colonic epithelial dysfunction following severe pancolitis, adverse effects of drugs or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO).

Thiopurine immunosuppressant and biological drugs used in CD are not free from side effects, such as acquiring infections.

Investigation of SIBO in an observational and prospective study in patients with CD in remission, included consecutively from 2004 to 2010. Assessment of the relationship with the immunosuppressant and biological treatment.

This study showed no association between drug treatment and bacterial overgrowth. These results may explained because the treatment promotes better disease control.

SIBO is an imbalance of intestinal microflora, which can show a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from mild and unspecific intestinal symptoms to a severe malabsorption syndrome. HGBT and lactulose breath test are currently used in clinical practice for diagnosis of SIBO. CD is a complex chronic inflammatory bowel disease with an unpredictable course, which in most cases, is accompanied by periodic recurrence and inactivity.

This manuscript evaluated prospectively the influence of thiopurines and biological agents on the development of SIBO in patients with inactive CD. Factors promoting the development of SIBO included strictures, fistulae, and motility disturbances, which are all present in patients with CD. There are few studies published in the literature on this topic; therefore, I reviewed the present manuscript with much interest.

P- Reviewer: Papamichael KX, Trifan A, Zhao HT S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Management of Crohn‘s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465-483; quiz 464, 484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 619] [Cited by in RCA: 591] [Article Influence: 36.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, Beaugerie L, Karagiannis J, Allez M, Ochsenkühn T, Orchard T, Rogler G, Louis E. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:7-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 792] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gasbarrini A, Corazza GR, Gasbarrini G, Montalto M, Di Stefano M, Basilisco G, Parodi A, Usai-Satta P, Vernia P, Anania C. Methodology and indications of H2-breath testing in gastrointestinal diseases: the Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29 Suppl 1:1-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Castiglione F, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Rispo A, Petrelli G, Amalfi G, Cozzolino A, Cuccaro I, Mazzacca G. Orocecal transit time and bacterial overgrowth in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:63-66. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mishkin D, Boston FM, Blank D, Yalovsky M, Mishkin S. The glucose breath test: a diagnostic test for small bowel stricture(s) in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:489-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Klaus J, Spaniol U, Adler G, Mason RA, Reinshagen M, von Tirpitz C C. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth mimicking acute flare as a pitfall in patients with Crohn’s Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rutgeerts P, Ghoos Y, Vantrappen G, Eyssen H. Ileal dysfunction and bacterial overgrowth in patients with Crohn’s disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1981;11:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Afif W, Loftus EV. Safety profile of IBD therapeutics: infectious risks. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:691-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Reddy JG, Loftus EV. Safety of infliximab and other biologic agents in the inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:837-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Toruner M, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Egan LJ. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:929-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 719] [Cited by in RCA: 747] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Romagnuolo J, Schiller D, Bailey RJ. Using breath tests wisely in a gastroenterology practice: an evidence-based review of indications and pitfalls in interpretation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1113-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Singh VV, Toskes PP. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;5:365-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | King CE, Toskes PP. Comparison of the 1-gram [14C]xylose, 10-gram lactulose-H2, and 80-gram glucose-H2 breath tests in patients with small intestine bacterial overgrowth. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:1447-1451. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Stotzer PO, Kilander AF. Comparison of the 1-gram (14)C-D-xylose breath test and the 50-gram hydrogen glucose breath test for diagnosis of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Digestion. 2000;61:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kerlin P, Wong L. Breath hydrogen testing in bacterial overgrowth of the small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:982-988. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lo WK, Chan WW. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:483-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |