Published online Oct 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13936

Revised: June 10, 2014

Accepted: June 25, 2014

Published online: October 14, 2014

Processing time: 191 Days and 20.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of stents in treating patients with anastomotic site obstructions due to cancer recurrence following colorectal surgery.

METHODS: The medical records of patients who underwent endoscopic self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) insertion for colorectal obstructions between February 2004 and January 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. During the study period, a total of 218 patients underwent endoscopic stenting for colorectal obstructions. We identified and examined the patients who underwent endoscopic stenting for obstructions caused by cancer recurrence at the anastomotic site following colorectal surgeries for primary colorectal cancer.

RESULTS: Five consecutive patients [mean age, 56.4 years (range: 39-82 years); 4 women, 1 man] underwent endoscopic stenting for obstructions caused by cancer recurrence at the anastomotic site following colorectal surgeries for primary colorectal cancer. Technical and clinical success was achieved in all 5 patients, without any early complications. During follow-up, 3 patients did not need further intervention, prior to their death, after the first stent insertion; thus, the overall success rate was 3/5 (60%). Perforations occurred in 2 patients who required a second SEMS insertion due to re-obstruction; none of the patients experienced stent migration.

CONCLUSION: SEMS placement is a promising treatment option for patients who develop obstructions of their colonic anastomosis sites due to cancer recurrence.

Core tip: No studies have investigated the clinical outcome of the use of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) for the palliation of patients with obstructions of colorectal anastomosis sites due to cancer recurrence, following primary colorectal cancer surgery. The mechanism of obstruction differs between primary colorectal cancer and recurrence-related obstructions of the anastomotic site; the scar tissue at the anastomosis site may reduce the radial expansion force of SEMS in obstructions caused by intraluminal tumor growth. However, based on our experience, SEMS placement seems a promising treatment for patients who develop recurrence-related anastomotic site obstructions.

- Citation: Kim JH, Lee JJ, Cho JH, Kim KO, Chung JW, Kim YJ, Kwon KA, Park DK, Kim JH. Endoscopic stenting for recurrence-related colorectal anastomotic site obstruction: Preliminary experience. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(38): 13936-13941

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i38/13936.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13936

The incidence of recurrence at colonic anastomotic sites, after curative resection of colorectal cancer, is relatively low compared to recurrence at other sites, such as the liver and lung. In patients with colorectal cancer, the postoperative recurrence rate in patients with stage I-III cancer is 3%-31%. Among patients experiencing recurrence, the percentage of patients with recurrence at the anastomosis site was reported to be 2.4%[1].

In some patients with anastomotic obstructions due to cancer recurrence, curative surgery is nearly impossible because of the patient’s poor general condition due to the advanced stage of the primary cancer. In patients with colorectal obstructions, the post-palliative surgery morbidity rates range from 21% to 44%, and are accompanied by mortality rates of 13%-16%[2]. Previous reports[2-6] have provided strong evidence regarding the effectiveness of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) in these patients, including high success rates, fewer complications, and increased quality of life. However, reports on the clinical outcome of the use of SEMS for palliation in a homogenous population of patients with anastomotic obstructions due to cancer recurrence, after colorectal cancer surgery, have not been published.

Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and palliative benefits of SEMS placement as the initial interventional approach in patients with colonic obstruction at anastomosis site due to cancer recurrence. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing the efficacy of SEMS use in the treatment of such patients.

The medical records of 218 patients undergoing endoscopic stenting for colorectal obstruction at Gachon University Gil Medical Center (Incheon, South Korea), between February 2004 and January 2014, were retrospectively reviewed. The inclusion criteria were previous surgery for primary colorectal cancer, presence of obstructive symptoms and signs, endoscopic and radiologic evidence of colorectal obstructions, and cancer recurrence at the anastomotic site.

SEMS insertion was performed, as previously described[2,3]; informed consent was obtained from each patient after explaining the endoscopic procedure. All the patients underwent computed tomography (CT) before colonic stenting, and cleansing enemas were performed a few hours before the stenting. A colonoscope (CF-Q240L; Olympus Optical Corp., Tokyo, Japan) or a two-channel therapeutic endoscope (GIF-2T240; Olympus) was introduced into each obstructive lesion, and a guidewire was placed across the stricture, under endoscopic and/or fluoroscopic guidance. The length of the stricture was measured using CT and/or barium enemas and/or fluoroscopy using water-soluble contrast. The length of the chosen SEMS was at least 3 cm longer than the length of the lesion. A covered or uncovered SEMS was chosen by the endoscopist. Niti-S stents (Taewoong Medical Co., Seoul, South Korea) were used in the present series. Balloon dilatation of the stricture was not performed.

Technical success was defined as the successful insertion of a stent across the entire length of the stricture. Clinical success was defined as the relief of obstructive symptoms and signs within 72 h of stent placement. The overall clinical success was defined as the successful maintenance of stent function and the lack of need for further treatment of anastomotic site obstruction during the follow-up period. Anastomotic recurrence was defined as the recurrence of cancer indicated by endoscopic biopsy or colonoscopy as well as the presence of CT findings showing anastomotic obstruction associated with cancer recurrence. Event-free survival was defined as the time from SEMS insertion to re-intervention, such as surgery or re-stenting. Overall survival was defined as the time from SEMS insertion to death from any cause.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Ver. 12.0 for Windows; IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM, Armonk, NY). Continuous variables are presented as means (range), whereas categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages.

Five consecutive patients [mean age, 56.4 (range, 39-82) years; 4 women, 1 man] were identified as having undergone endoscopic stenting for anastomotic site obstruction due to cancer recurrence. The anastomosis sites were located at a mean distance of 11.2 cm (range: 7-15 cm) above the anal verge in these patients. The mean interval between the first stent insertion and the colonic anastomosis was 352.2 d (range: 208-488 d). Anastomosis was performed using the stapler technique in all patients; none of the patients experienced postoperative anastomotic leakage, and none received neoadjuvant therapy (4 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy). The other baseline patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Case No. | Gender | Age | Diagnosis (stage) | Differentiation | Initial surgery | Diverting stoma | Level of anastomosis site (cm) | Type of anastomosis (mm) | Interval IS (d) | Interval CF (d) | Adjuvant therapy |

| 1 | F | 39 | Sigmoid colon cancer (IIIB) | MD | Hartmann's operation | Yes | 14 | EEA (28) | 47 | 340 | CTX |

| 2 | F | 47 | Upper rectal cancer (IIIB) | MD | Hartmann's operation | Yes | 10 | EEA (28) | 70 | 448 | CTX |

| 3 | M | 82 | Sigmoid colon cancer (IIIC) | PD | Low anterior resection | No | 10 | EEA (28) | NA | 277 | No |

| 4 | F | 67 | Sigmoid colon cancer (IIIC) | MD | Hartmann's operation | Yes | 7 | EEA (31) | 218 | 488 | CTX |

| 5 | F | 47 | Sigmoid colon cancer (IIIC) | MD | Lapaloscopic anterior resection | No | 15 | EEA (28) | NA | 208 | CTX |

A total of 7 stents were deployed in the 5 patients throughout the study period (Table 2). During the initial stent deployment, 4 SEMS insertions involved uncovered stents, with technical and clinical success being achieved in all patients, without any early complications. During the follow-up period, 3 patients achieved overall success and did not need further intervention prior to their deaths; 2 patients did not achieve overall success.

| Case No. | Stent characteristics | AT after stenting | Cause of failure | Need for surgery | Survival (d) | Outcome | |||

| Type | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Event-free | Overall | |||||

| 1 | Uncovered | 100 | 24 | No | Re-obstruction | Yes | 13 | 34 | Surgery performed due to insufficient function, 10 d after the second SEMS insertion. Died of complications 11 d after the surgery |

| 2 | Uncovered | 120 | 20 | No | NA | No | 93 | 93 | Died due to multiple organ failure, with disease progression |

| 3 | Uncovered | 60 | 24 | No | NA | No | 66 | 66 | Died of pneumonia |

| 4 | Covered | 60 | 20 | No | NA | No | 4 | 4 | Died of myocardial infarction |

| 5 | Uncovered | 60 | 24 | CTX | Re-obstruction | Yes | 96 | 136 | Perforation occurred 26 d after the second SEMS insertion. Currently alive |

One of the 2 patients who did not achieve overall success experienced re-obstruction 13 d after the first SEMS insertion and underwent a second SEMS insertion (uncovered stent, 24 mm × 120 mm). Obstructive symptoms and signs were aggravated, again, 10 d after the second SEMS insertion; therefore, the patient underwent a re-operation. The perforation site was not detected, but the patient was diagnosed as having a microperforation, based on the operative findings. The patient died of disseminated intravascular coagulation and hepatic failure 11 d after surgery.

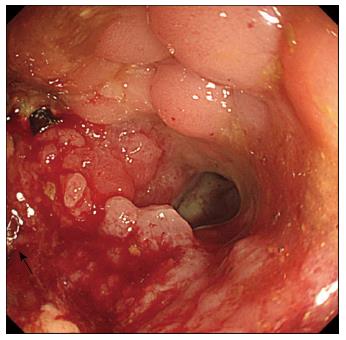

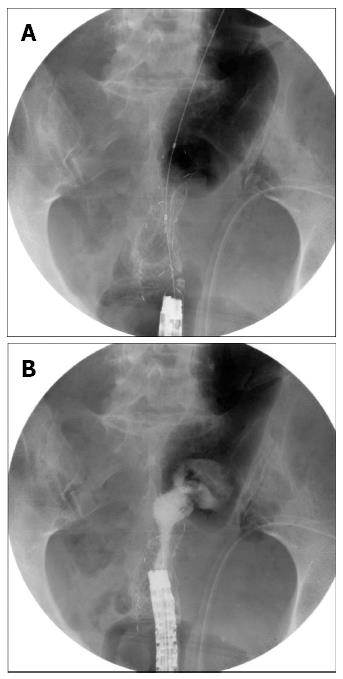

The second patient who did not achieve overall success demonstrated re-obstruction 96 d after the first SEMS insertion, and underwent a second SEMS insertion (Figures 1 and 2). The symptoms and signs improved after the second SEMS (uncovered stent, 24 mm × 80 mm) insertion and stent patency was well maintained. However, the patient experienced acute abdominal pain 26 d after the second SEMS insertion and underwent emergent surgery. The patient demonstrated a 1-cm perforation at the SEMS insertion site, and a colostomy was performed. The patient had been receiving intravenous dexamethasone for cauda equina syndrome, which was initiated 20 d before the perforation developed, along with radiation therapy (total dose: 30 Gy/10 fractions) to the thoracic and lumbar spine. The patient had also been prescribed regorafenib (oral multi-kinase inhibitor), which was initiated 4 d before the perforation developed.

Healing occurs at the site of a colonic anastomosis after surgery. The healing process in the intestinal wall occurs in a sequence similar to that observed during skin wound healing. During the maturation phase of the healing process, collagen cross-linking and remodeling occurs, which ultimately leads to scar formation[7,8]. Strictures rarely occur in the absence of cancer recurrence at the anastomosis site (7% of patients)[9]; only a few of these patients experience obstructive symptoms and signs postoperatively. Among those experiencing obstruction, treatment normally includes laxatives, balloon dilation, or surgical revision of the anastomosis, according to the severity of the symptoms[10,11]. Recently, SEMS have been reported to be an effective treatment for benign strictures, including those at the anastomotic site, in small case series[12-17]. In patients with obstructions of colorectal anastomosis sites due to cancer recurrence, the obstruction occurs via a different mechanism. Irrespective of the presence or absence of a stricture at the anastomosis site, a combination of scar formation and intraluminal tumor growth leads to the obstruction of the anastomotic site due to cancer recurrence.

Many studies[4,5,18] have reported the efficacy of SEMS for treating malignant colorectal obstructions caused by the presence of space-occupying masses in the intestinal lumens; however, SEMS have rarely been reported for the treatment of recurrence-related obstructions at the site of the anastomosis due to the rarity of the condition. SEMS insertion is currently not an approved treatment for obstructions of the anastomosis site[19]. However, a less invasive modality may be needed, depending on the patient’s general condition, underlying disease status, or refusal to undergo surgery. Moreover, the clinical outcomes of SEMS placement in cases of recurrence-related obstruction of the anastomotic site have not been reported. Thus, we reported our preliminary experience (over 10 years) of 5 patients who underwent endoscopic stenting for the treatment of anastomotic site obstructions due to cancer recurrence.

Scars, formed during the healing process at the anastomotic site, may reduce the radial expansion of SEMS in the obstruction caused by intraluminal tumor growth. Therefore, the success rate observed with the SEMS, in this study, was higher than expected; all 5 patients achieved technical and clinical success. Furthermore, 3 of the patients did not require additional treatment prior to their death. However, additional experience is needed to better determine the long-term patency in these patients.

Only a few studies have reported the use of SEMS, even for treating non-recurrence related obstructions of colonic anastomosis sites; therefore, there are few data regarding the incidence of complications. Similar to benign strictures, anastomotic site strictures have relatively smooth surfaces and occur over short segments. Migration of the SEMS is a common complication of their use in the treatment of benign strictures[14,20]. However, the 2 cases reported herein who did not achieve overall success, experienced re-obstruction rather than stent migration. This may be due to the use of uncovered stents and ongoing tumor growth at the stent insertion site, unlike that observed in the cases of benign strictures.

The patients included in our study had undergone endoscopic stenting because of poor general condition and/or advanced cancer stage and/or refusal of major palliative surgery. However, there was no clear consensus for the treatment with colonic stents in patients with anastomotic site obstructions due to cancer recurrence. Therefore, the endoscopy specialists chose the SEMS type (covered vs uncovered) on an individual basis. Most of the patients received an uncovered SEMS to minimize stent migration. However, the re-obstruction rate in patients with uncovered SEMS was reportedly higher than in patients with covered SEMS. In a recent report, the use of a covered SEMS for benign colonic strictures was shown to be effective and safe, despite a high incidence of stent migration[21]. Unfortunately, the report was mainly focused on treatment outcomes of benign colonic stricture. In the present study, the main purpose was to provide long-term palliation to patients with anastomotic obstructions due to cancer recurrence following colorectal surgery.

Perforation is another important complication of SEMS insertion, which affects the oncologic outcome[22]. Specifically designed stents (WallFlex® stents, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States), used in conjunction with balloon dilation and bevacizumab chemotherapy, were considered to contribute to stent-related perforations in previous studies[23-25]. In the present study, perforation was experienced by 2 patients who required a second SEMS insertion due to re-obstruction. The patient with a microperforation experienced a slight improvement in symptoms and signs, with partial colonic decompression, after the second SEMS insertion. Delaying surgery and adopting a wait-and-see approach might have contributed to the formation of the microperforation. The second patient with a perforation was confirmed to have a 1-cm perforation at the proximal portion of the SEMS insertion site; the patient did not have any risk factors that might have been associated with the perforation, but radiation therapy and/or regorafenib treatment may have contributed to the risk of perforation.

Based on our experience, SEMS use seems to be promising as a treatment option for patients with anastomotic obstructions due to cancer recurrence following primary colorectal surgery. However, perforations were serious complications associated with patients experiencing re-obstructions that were treated with second SEMS insertions. Therefore, the placement of additional SEMS should be carefully considered. Although the use of SEMS seems to be a promising treatment modality, only a small number of recurrence-related anastomotic obstruction patients have been treated with these devices; therefore, additional data are needed to determine their long-term efficacy and safety.

Although the use of self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) for colorectal obstructions is preferred over emergency surgery, their associated clinical outcomes for palliation in a homogenous population of patients, with anastomotic obstructions due to cancer recurrence, has not been demonstrated. In patients with obstructions of colorectal anastomosis sites due to cancer recurrence, the obstruction occurs via a different mechanism. Irrespective of the presence or absence of a stricture at the anastomosis site, a combination of scar formation and intraluminal tumor growth leads to the obstruction of the anastomotic site.

The authors aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and palliative benefits of SEMS placement as the initial interventional approach in patients with colonic obstruction at the anastomosis site due to cancer recurrence. This is the first report describing the efficacy of SEMS use in the treatment of such patients.

Based on this study’s results, SEMS use seems to be promising as a treatment option for patients with anastomotic obstructions due to cancer recurrence following primary colorectal surgery. However, perforations were serious complications associated with patients experiencing re-obstructions that were treated with second SEMS insertions. Therefore, the placement of additional SEMS should be carefully considered. Although the use of SEMS seems to be a promising treatment modality, only a small number of recurrence-related anastomotic obstruction patients have been treated with these devices; therefore, additional data are needed to determine their long-term efficacy and safety.

Many studies have reported the efficacy of SEMS for treating malignant colorectal obstructions caused by the presence of space-occupying masses in the intestinal lumens; however, SEMS insertion is currently not an approved treatment for obstructions of the anastomosis site. However, a less invasive modality may be needed, depending on the patient’s general condition, underlying disease status, or refusal to undergo surgery. Therefore, the authors’ findings may aid therapeutic decision-making when considering surgery or endoscopic stenting in these patients.

This article is an interesting report of recurrent cancer in colonic anastomoses. The authors state that they inserted a second uncovered stent in each of two patients with neoplastic anastomotic re-obstructions.

P- Reviewer: Fiori E S- Editor: Nan J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Kobayashi H, Mochizuki H, Sugihara K, Morita T, Kotake K, Teramoto T, Kameoka S, Saito Y, Takahashi K, Hase K. Characteristics of recurrence and surveillance tools after curative resection for colorectal cancer: a multicenter study. Surgery. 2007;141:67-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim JH, Ku YS, Jeon TJ, Park JY, Chung JW, Kwon KA, Park DK, Kim YJ. The efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for malignant colorectal obstruction by noncolonic malignancy with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1228-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee JJ, Chung JW, Kwon KA, Park DK, Kim JH, Hahm KB. The efficacy of self-expanding metal stents for colorectal obstruction with unresectable stage IVB colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:2472-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sebastian S, Johnston S, Geoghegan T, Torreggiani W, Buckley M. Pooled analysis of the efficacy and safety of self-expanding metal stenting in malignant colorectal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2051-2057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 504] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Fan YB, Cheng YS, Chen NW, Xu HM, Yang Z, Wang Y, Huang YY, Zheng Q. Clinical application of self-expanding metallic stent in the management of acute left-sided colorectal malignant obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:755-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lamazza A, Fiori E, Schillaci A, DeMasi E, Pontone S, Sterpetti AV. Self-expandable metallic stents in patients with stage IV obstructing colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:2931-2936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ho YH, Ashour MA. Techniques for colorectal anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1610-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hendriks T, Mastboom WJ. Healing of experimental intestinal anastomoses. Parameters for repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:891-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Weinstock LB, Shatz BA. Endoscopic abnormalities of the anastomosis following resection of colonic neoplasm. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:558-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Garcea G, Sutton CD, Lloyd TD, Jameson J, Scott A, Kelly MJ. Management of benign rectal strictures: a review of present therapeutic procedures. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1451-1460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kwon YH, Jeon SW, Lee YK. Endoscopic management of refractory benign colorectal strictures. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:472-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Branche J, Attar A, Vernier-Massouille G, Bulois P, Colombel JF, Bouhnik Y, Maunoury V. Extractible self-expandable metal stent in the treatment of Crohn’s disease anastomotic strictures. Endoscopy. 2012;44 Suppl 2 UCTN:E325-E326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Toth E, Nielsen J, Nemeth A, Wurm Johansson G, Syk I, Mangell P, Almqvist P, Thorlacius H. Treatment of a benign colorectal anastomotic stricture with a biodegradable stent. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E252-E253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Geiger TM, Miedema BW, Tsereteli Z, Sporn E, Thaler K. Stent placement for benign colonic stenosis: case report, review of the literature, and animal pilot data. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1007-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Small AJ, Young-Fadok TM, Baron TH. Expandable metal stent placement for benign colorectal obstruction: outcomes for 23 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:454-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Guan YS, Sun L, Li X, Zheng XH. Successful management of a benign anastomotic colonic stricture with self-expanding metallic stents: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3534-3536. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lee KJ, Kim SW, Kim TI, Lee JH, Lee BI, Keum B, Cheung DY, Yang CH. Evidence-based recommendations on colorectal stenting: a report from the stent study group of the korean society of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:355-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Frago R, Ramirez E, Millan M, Kreisler E, del Valle E, Biondo S. Current management of acute malignant large bowel obstruction: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2014;207:127-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McLoughlin MT, Byrne MF. Endoscopic stenting: where are we now and where can we go? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3798-3803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Suzuki N, Saunders BP, Thomas-Gibson S, Akle C, Marshall M, Halligan S. Colorectal stenting for malignant and benign disease: outcomes in colorectal stenting. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1201-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vanbiervliet G, Bichard P, Demarquay JF, Ben-Soussan E, Lecleire S, Barange K, Canard JM, Lamouliatte H, Fontas E, Barthet M. Fully covered self-expanding metal stents for benign colonic strictures. Endoscopy. 2013;45:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Søreide K. Emergency management of acute obstructed left-sided colon cancer: loops, stents or tubes? Endoscopy. 2013;45:247-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khot UP, Lang AW, Murali K, Parker MC. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of colorectal stents. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1096-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van Hooft JE, Fockens P, Marinelli AW, Timmer R, van Berkel AM, Bossuyt PM, Bemelman WA. Early closure of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgery for stage IV left-sided colorectal cancer. Endoscopy. 2008;40:184-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cheung DY, Lee YK, Yang CH. Status and literature review of self-expandable metallic stents for malignant colorectal obstruction. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:65-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |