Published online Oct 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13607

Revised: April 3, 2014

Accepted: May 19, 2014

Published online: October 7, 2014

Processing time: 254 Days and 19.7 Hours

We report our experience with potential donors for living donor liver transplantation (LDLT), which is the first report from an area where there is no legalized deceased donation program. This is a single center retrospective analysis of potential living donors (n = 1004) between May 2004 and December 2012. This report focuses on the analysis of causes, duration, cost, and various implications of donor exclusion (n = 792). Most of the transplant candidates (82.3%) had an experience with more than one excluded donor (median = 3). Some recipients travelled abroad for a deceased donor transplant (n = 12) and some died before finding a suitable donor (n = 14). The evaluation of an excluded donor is a time-consuming process (median = 3 d, range 1 d to 47 d). It is also a costly process with a median cost of approximately 70 USD (range 35 USD to 885 USD). From these results, living donor exclusion has negative implications on the patients and transplant program with ethical dilemmas and an economic impact. Many strategies are adopted by other centers to expand the donor pool; however, they are not all applicable in our locality. We conclude that an active legalized deceased donor transplantation program is necessary to overcome the shortage of available liver grafts in Egypt.

Core tip: This is the first case series from a country where a deceased donor liver transplantation program is not available and the shortage of living liver donors is high. We report our experience regarding the problem of excluded donors and possible strategies to overcome this problem. We hope that this experience will be of benefit to the readers of the World Journal of Gastroenterology.

- Citation: Wahab MA, Hamed H, Salah T, Elsarraf W, Elshobary M, Sultan AM, Shehta A, Fathy O, Ezzat H, Yassen A, Elmorshedi M, Elsaadany M, Shiha U. Problem of living liver donation in the absence of deceased liver transplantation program: Mansoura experience. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(37): 13607-13614

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i37/13607.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13607

Each center may have its own unique criteria for potential donors of living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) regarding the geographical and cultural backgrounds, however, each center must follow the current global standards of care[1-4]. In Egypt, a deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) program is still awaited, thus, LDLT is the only hope for patients with end-stage liver disease or hepatocellular carcinoma in the presence of cirrhosis[5]. Our experience regarding the short- and long-term impact of liver transplantation on living donors has been published in a previous study[5].

Few studies have examined the reasons for excluding living liver donors and its impact on transplantation. These studies have been conducted in countries where DDLT is allowed and the problem of donation is not so high. Most available articles are based on a small number of potential donors and some of these articles included donors who were excluded for reasons related to the recipient[6-9].

In this study, we investigated the impact of excluding living donors on patients, the transplant team and medical resources in the absence of a DDLT program. We discuss different possible strategies to overcome this problem and the expected outcome following the adoption of these strategies in our center.

This is a retrospective cohort study of excluded donors (n = 792) from potential donors (n = 1004) for LDLT using a right lobe graft during the period from May 2004 to December 2012 in the Liver Transplant Program, Gastrointestinal Surgical Center, Mansoura University, Egypt. Potential donors were any living donors who came to our center after the recipient had been informed of the accepted donor criteria. Excluded donors were those who were not permitted to undergo living liver donation to a certain recipient due to reasons related to the donor, irrespective if the decision was made by the transplant team, recipient, or the donor himself.

Data for this study were retrieved from the internal web-based registry system supplemented by paper-based records of the potential donors included in the medical files of the corresponding recipients. Data were collected and rearranged in a standardized manner including details on donor age, sex, body mass index (BMI), liver function tests, viral serological markers, results of liver biopsy and imaging studies if performed, cause and phase of exclusion, duration from the donor’s first visit to the exclusion decision, and the cost of any investigations and special consultations carried out.

Donor candidates were thoroughly evaluated according to the multidisciplinary protocol shown in Table 1. A multistep consent process involving two different surgeons and a hepatologist on separate occasions was used, during which the operative procedure and potential complications were described in detail. Donors were informed that the risks of morbidity and mortality were 40% and 0.5%, respectively[5].

| Potential donor: Is any living donor at our center after the recipient is informed of the accepted donor criteria. The criteria for living liver donors include an apparently healthy relative of the recipient aged between 21 and 45 years. Recipient, donor and their families are informed regarding the risks and benefits of right lobe hepatectomy for LDLT and both the donor and the recipient must sign an informed written consent to proceed to the evaluation process |

| Phase I: Confirmation of the relation between the living donor and the candidate recipient by the independent legal and ethical committee, confirmation of being within the accepted age limits, assessment of BMI, initial anesthetic and surgical evaluation, confirmation of ABO compatibility, complete blood count (CBC) and biochemistry assays, pregnancy test, abdominal Doppler ultrasound, serological tests for hepatitis C and B viruses (serum HCV RNA qualitative and quantitative assay using PCR, HBV surface antigen, HB core antibody, HB e antigen, HB e antibody, HB surface antibody), serological assessment for different viruses (human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Herpes virus I and II, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Chagas disease and syphilis), electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography, plain X-ray of the chest, exclusion of specific liver diseases (ferritin, transferrin, and serum iron), and reassessment after previous investigations |

| Phase II: Liver biopsy for assessment of degree of steatosis and detection of any pathological conditions |

| Phase III: Hepatic angiography to delineate the anatomy of the portal vein, hepatic artery and hepatic veins. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is performed to assess the anatomy of the biliary system. Liver volumetry to assess the right lobe graft size, residual donor liver volume and graft-recipient weight ratio (GRWR). The donor is accepted if GRWR > 0.8 and the residual donor liver volume ≥ 30% |

| Phase IV: All donors must sign a written informed consent including agreement to participate in LDLT |

Non-related living donation was accepted only when the patient was approved by an independent ethical and legal committee and none of his relatives were suitable right liver lobe donors. The legal age of consent for donation in Egypt is 18 years when the recipient is a parent, otherwise it is 21 years. The upper age limit for living liver donation is 45 years. According to the 2006 Census held by the Central Agency for Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), only 6.27% of Egyptians are aged above 60 years[10]. This implies that most chronic diseases occur at a younger age in Egyptians in comparison to other populations. This justifies our choice of an upper age limit of 45 years, although many centers in other countries accept higher age limits, even greater than 60 years.

Routine liver biopsy in the living liver donor evaluation protocol is controversial. Some centers have adopted routine liver biopsy after unfortunate experiences with living donors including operation abortion and donor mortality due to undiscovered congenital lipodystrophy[6,11]. For safety, liver biopsy in living liver donors is necessary. Thus, liver biopsy is routinely performed by an experienced radiologist.

Liver biopsy is performed prior to imaging studies such as hepatic angiography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and liver volumetry to evaluate the anatomy of the vascular and biliary systems. Although the former is an invasive procedure, it is far less expensive (50 USD) than the imaging studies (500 USD). Also, liver biopsy had been performed in our center since 1974 to evaluate patients with portal hypertension for shunt operations and with this cumulative experience the procedure is almost risk-free. The burden of the donor evaluation costs is on the recipient with little support from the state. Therefore, we perform liver biopsy prior to imaging studies for economic reasons, especially as liver biopsy is almost risk-free in our center.

Donors with a BMI > 35 were re-evaluated after they committed to a successful weight loss program. Absolute exclusion criteria were ABO incompatibility, pregnancy, mental inadequacy, an underlying medical condition that was considered to increase the risk of complications, positive hepatitis B or C serology, underlying liver disease, steatosis > 30%, and abnormal anatomy considered by surgeons to increase the risk of hepatectomy or affect the remaining liver.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality of the data. Numerical data are presented as means and standard deviations or as medians with ranges. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS v. 20.

Between May 2004 and December 2012, we received 1004 potential donors in the Liver Transplant Program, Mansoura Gastrointestinal Surgical Center. Two hundred and twelve donors (21.1%) met the inclusion criteria for transplant surgery, while 792 candidates (78.8%) were excluded. Most of these donors were excluded during phase I (Table 2) of the evaluation protocol (n = 633, 79.9%), while exclusion in other phases was as follows (Table 3): phase II (n = 108, 13.6%), phase III (n = 48, 6.1%) and phase IV (n = 3, 0.4%).

| Phase | Step | n | Exclusion | n | % from the step |

| Phase I | Confirmation of the relative | 1004 | Non-related donor | 2 | 0.19 |

| Age | 1002 | Over age limit | 223 | 22.25 | |

| BMI | 779 | Overweight | 26 | 3.33 | |

| Underweight | 5 | 0.64 | |||

| Clinical evaluation | 748 | Uncontrolled HTN | 2 | 0.26 | |

| Initial surgical evaluation | 746 | Upper abdominal surgery | 6 | 0.8 | |

| Psychological evaluation | 740 | Algophobia | 1 | 0.13 | |

| Hesitation | 3 | 0.4 | |||

| ABO compatibility | 736 | ABO incompatibility | 102 | 13.85 | |

| 634 | Withdrawal | 23 | 3.62 | ||

| CBC and biochemistry | 611 | thrombocytopenia | 3 | 0.49 | |

| uncontrolled DM | 4 | 0.65 | |||

| elevated liver enzymes | 7 | 1.14 | |||

| hyperbilirubinemia | 2 | 0.32 | |||

| hypoalbuminemia | 1 | 0.16 | |||

| 594 | Family refusal | 5 | 0.84 | ||

| Withdrawal | 6 | 1.01 | |||

| Pregnancy test | 583 | Positive test | 16 | 2.74 | |

| Abdominal US | 567 | Splenomegaly | 1 | 0.17 | |

| Fatty liver | 1 | 0.17 | |||

| 565 | Withdrawal | 29 | 5.13 | ||

| Serological assessment | 536 | HCV positive | 39 | 7.27 | |

| HBV positive | 34 | 6.34 | |||

| CMV positive | 7 | 1.3 | |||

| EBV positive | 1 | 0.18 | |||

| HCV and HBV positive | 6 | 1.11 | |||

| HCV and CMV positive | 1 | 0.18 | |||

| 448 | Withdrawal | 9 | 2.0 | ||

| Anesthetic reassessment | 439 | Smoker | 28 | 6.37 | |

| IHD | 2 | 0.45 | |||

| Rheumatic heart disease | 3 | 0.68 | |||

| Valvular heart disease | 3 | 0.68 | |||

| Atrial ectopics | 1 | 0.22 | |||

| 402 | Withdrawal | 31 | 7.71 |

| Phase | Step | n | Exclusion | n | % from the step |

| Phase II | Liver biopsy | 371 | Moderate steatosis | 16 | 4.31 |

| Severe steatosis | 9 | 2.42 | |||

| Portal tract fibrosis | 27 | 7.27 | |||

| Bilharzial granuloma | 10 | 2.69 | |||

| Reactive hepatitis change | 4 | 1.07 | |||

| Focal portal infiltrate | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| Portal lymphocyte infiltrate | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| Hemosiderosis | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| Focal necrotic areas | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| 301 | Withdrawal | 38 | 12.62 | ||

| Phase III | Volumetry and anatomical assessment | 263 | Portal venous variants | 2 | 0.76 |

| Biliary variants | 6 | 2.28 | |||

| hepatic venous variants | 8 | 3.04 | |||

| hepatic venous and biliary variants | 1 | 0.38 | |||

| hepatic and portal venous variants | 3 | 1.14 | |||

| Small for size graft | 15 | 5.70 | |||

| Small residual left lobe | 4 | 1.50 | |||

| 224 | Withdrawal | 9 | 4.01 | ||

| Phase IV | Informed consent | 215 | Withdrawal | 3 | 1.39 |

| Donors underwent surgery | 212 |

The most frequent reason for donor exclusion was exceeding the upper age limit (n = 172, 21.7%), while 6.4% of potential donors (n = 51) were below the lower age limit. ABO incompatibility represented the 2nd most common cause of exclusion during phase I and the 3rd most common cause in the whole evaluation process with a ratio of 12.9% (n = 102). 2% of potential donors (n = 16) were found to be pregnant. Twenty-six (3.3%) candidate donors were excluded due to BMI > 30, and 5 donors (0.6%) were excluded because they were underweight. One donor was excluded because he had algophobia. Two potential donors were excluded as they were unrelated to the patient, which was discovered during confirmation by the independent ethical and legal committee.

One hundred and forty-eight donors (18.7%) withdrew during the evaluation process. Most of them withdrew during the first phase (n = 98), while 38 potential donors withdrew during the second phase and 9 withdrew during the third phase. Three donors withdrew after completion of the evaluation process on the night of surgery. Three candidate donors expressed much hesitation during first interviews with the transplant team and were excluded. Interestingly, 5 donors were excluded as their families refused donation. Of these 5 cases with family refusal, one father refused his daughter’s donation to himself and a husband refused his wife’s donation to her mother. Of the potential donors, 6 donors were excluded because they had previous nephrectomy and two of them frankly stated they wanted a renal transplant.

In a country where hepatitis C virus (HCV) is endemic, 39 potential donors (4.9%) were excluded because they were serologically positive for HCV infection. Thirty-four (3.4%) were serologically positive for HBV, 6 candidates (0.8%) were positive for both HCV and hepatitis B virus (HBV), 7 candidates (0.9%) were positive for cytomegalovirus (CMV), one candidate was positive for both HCV and CMV and one candidate was serologically positive for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Ten candidates had abnormal liver function tests in the form of elevated liver transaminase enzymes (n = 7), elevated serum bilirubin (n = 2) and hypoalbuminemia with hypoprothrombinemia (n = 1). One donor was excluded because he had fatty liver on ultrasound. One of the excluded donors had splenomegaly and 3 candidates were excluded because they had thrombocytopenia.

The anesthesia team excluded 28 candidates (3.5%) because they were smokers who refused to stop smoking before surgery. They excluded other potential donors because they had uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (n = 4), uncontrolled hypertension (n = 2), ischemic heart disease (n = 2), rheumatic heart disease (n = 3), valvular heart disease (n = 3), and atrial ectopic activity (n = 1).

Twenty-five candidates (3.2%) were excluded because they had moderate to severe macrovesicular steatosis on liver biopsy. Many donors were also excluded during assessment in phase II following liver biopsy which revealed portal tract fibrosis (n = 27, 3.4%), active bilharzial granuloma (n = 10, 1.3%), reactive hepatitis changes (n = 4, 0.5%), focal portal infiltrate and interface hepatitis (n = 1, 0.1%), portal lymphocytic infiltrate (n = 1, 0.1%), mild hemosiderosis (n = 1, 0.1%) and hepatic focal necrotic areas (n = 1, 0.1%).

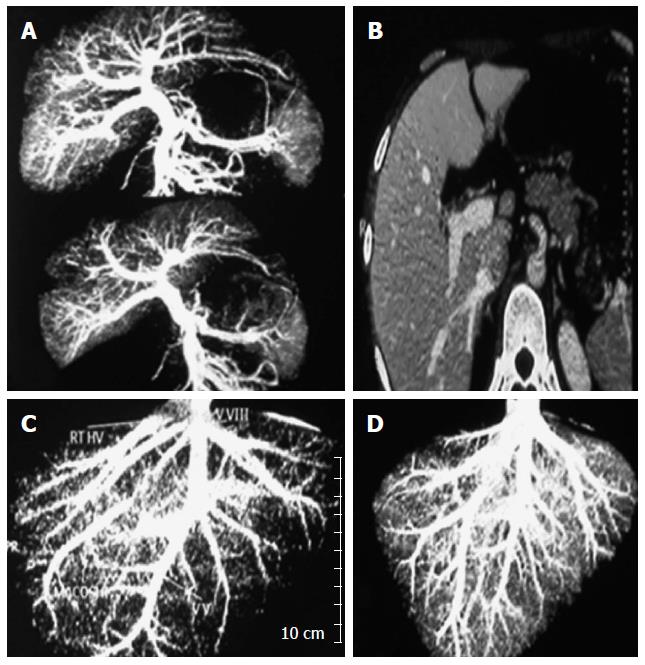

During phase III of evaluation, 15 candidates (1.9%) were excluded because liver volumetry revealed decreased right lobe size suspected to cause small for size graft, while 4 donors had a small left lobe which would result in inadequate reserve in the donor after surgery. Anatomical assessment by angiography and MRCP excluded many candidates because of unsuitable hepatic venous variants (n = 9), unsuitable biliary variants (n = 6), unsuitable portal venous variant (n = 1), unsuitable hepatic and portal venous variants (n = 3) and unsuitable hepatic venous and biliary variants (n = 1).

Of 212 patients who underwent LDLT, 204 patients (96.2%) had an experience with an excluded donor with a median number of 3 donors per recipient (range 1 to 56 excluded donors). Eight patients (3.7%) did not experience donor exclusion and they underwent liver transplantation. Fourteen patients did not have a suitable living related donor and died due to end-stage liver disease. Twelve patients travelled abroad and underwent surgery in countries where LDLT is legalized, particularly China (n = 7).

The decision to withdraw was made by the donor in 148 cases and by pressure from family in 5 cases. The exclusion decision was made by the transplant team in 639 cases. The median duration between the candidate’s first visit to our center and the exclusion or withdrawal date was 3 d ranging from 1 d (n = 151) to 47 d (n = 1).

The average cost of the investigations carried out for donor assessment in phase I, phase II and phase III was 150 USD, 200 USD and 700 USD, respectively. 1004 candidates entered phase I and 371 completed phase II. 301 candidates completed phase II and 224 potential donors completed phase III. Of those who completed phase III, 9 candidates withdrew and 215 completed Phase IV, after which 3 patients withdrew and 212 underwent transplant surgery. The median cost of the investigations performed for the excluded donor evaluations was 70 USD ranging from 35 USD (n = 103) to 885 LE Should this be USD? (n = 3). 264 donors (33.3%) were excluded without any need for special investigation. The burden of the expenses for donor evaluation lies with the recipient.

There is a worldwide paucity of liver donors in countries where deceased, living and domino liver transplants are all available, while in Egypt there is the problem of endemic hepatitis C liver cirrhosis with only living donors available. Through our experience with 1004 potential living donors, we encountered a lot of problems that involved the patients and transplant team; some of these problems had social roots with ethical and economic implications. This study describes the importance of a DLT program even after adoption of various strategies to expand the living donor pool, although we believe that it should not be adopted until after public debate and agreement.

A number of studies have detailed the evaluation protocol for living liver donors. Although donor exclusion is discussed in the context of reporting the experience with LDLT[11,12], to our knowledge, very few reports have exclusively discussed the impact of donor exclusion[6-9]. Apart from differences in the evaluation protocols between these reports, some authors excluded donors due to reasons related to the recipient in their study. This absence of uniform criteria for the presentation of data makes it difficult to compare our study with previous studies. We believe that this is the first study of a large number of potential donors from an area where there is no DLT program.

The evaluation of living donors for LDLT is a stepwise process consisting of a comprehensive medical work-up, psychological assessment and accurate anatomical delineation. Donor evaluation is an expensive labor-intensive and time-consuming process. The evaluation process should start with non-invasive steps, which are less expensive and detect a greater number of unsuitable donors and then progress to more invasive and expensive tests[6]. Based on our above-mentioned evaluation protocol, 26.62% of potential donors were excluded before undergoing any investigations.

In our series, 6.9% of potential donors were excluded based on abnormal liver biopsy mainly due to steatosis (2.48%) or bilharzial liver insult in the form of active granuloma or portal tract fibrosis (3.67%). This ratio is lower than the ratio reported in other studies by Valentín-Gamazo et al[6] (8%), Pomfret et al[13] (22%) and Marcos[14] (17%).

Donor withdrawal during, or even after, evaluation for LDLT is an inevitable cause of donor exclusion. An ethical dilemma occurs when a competent donor candidate gives voluntary informed consent, but his family refuses his donation. Although we adopt patient-centered Western bioethics, undue pressure from the candidate’s family puts the team in a difficult situation. How can you proceed to surgery when the family calls the police to the hospital alleging that the donor is coerced? Should you not consider a husband who threatens to divorce his wife if she donates her right liver lobe to her mother? These dilemmas are not well discussed in the literature, although there is a significant focus on donors under pressure from the family to donate to a relative, not the reverse!

In our experience, 22.21% of potential donors were excluded because their age was outside the accepted age range in our center, which is between 21 and 45 years old. The accepted age for living liver donation varies between centers. The lower age limit is determined by the law which defines the accepted age of consent[6,15]. In Egypt, the legal age of consent is 18 years old when the recipient is a parent, otherwise it is 21 years old. The upper age limit is variable and most centers exceed 50 years old and may even be up to 75 years old. Other centers consider old age a risk factor that if associated with other risk factors, such as nicotine abuse or hypertension, the donor is excluded, otherwise he is accepted[6,11,15,16]. In comparison to these populations, the National Census revealed that only about 6% of Egyptians are aged above 60 years and that is why we chose an upper age limit of 45 years old[10].

In this series, 10.15% of potential donors were excluded because of ABO incompatibility. Possible solutions include ABO incompatible LDLT and paired donor exchange. The main concern in ABO incompatible transplantation is antibody-mediated rejection (AMR). Prophylaxis against AMR includes antiCD20 antibody (rituximab), splenectomy, reinforced immunosuppression and local infusion of prostaglandin E1 (PgE1) and/or steroids[17-19]. ABO incompatible transplantation is less favorable than compatible transplantation due to inferior long-term patient survival[19-21]. Exchange donor transplant was first adopted in Korea in 2003. The two main principles of the procedure are equality and simultaneity meaning that the two pairs are operated on at the same time. The bad news is that the rate of paired donor exchange after long-term application in Korea did not exceed 10%[15].

Of 536 candidates who were serologically assessed for hepatitis B and C markers in our center, 14.9% of them were accidentally discovered to be serologically positive for HCV and/or HBV. Twenty-three potential donors were excluded because they were hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) positive and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) negative. This ratio was lower than those reported in endemic regions where it reached up to around 50% in potential donors[22]. There is a risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in naïve recipients for HBV who receive grafts from HBcAb positive donors[22,23]. Immunoprophylaxis in naïve recipients using hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG), lamivudine and vaccination is associated with a lower incidence of de novo infection[24]. However, the low prevalence of HBV infection together with the expensive postoperative prophylactic course (11700 USD), which the recipient cannot afford, has led to refusal of the use of donors with positive HBcAB.

Precise and accurate knowledge of the anatomy of hepatic vasculature and the biliary system is of paramount importance in planning the best resection and to lessen the risk of morbidity. With refinement of surgical techniques and cumulative experience, exclusion of potential donors due to anatomical variations has decreased over time, however, there are still conditions where donor safety necessitates “no go” hepatectomy even after starting the operation[25]. In our experience, 3.38% of potential donors were excluded on an anatomical and volumetric basis. Examples of cases excluded due to anatomical and volumetric considerations are shown in Figure 1.

Due to legislative obstacles supported by social background, deceased donor liver transplantation is not yet available in Egypt. The paucity of suitable willing living donors and an absence of grafts from deceased donors have resulted in many Egyptian patients seeking transplants abroad. In nearly all cases, the follow-up and management of post-transplant complications is carried out in Egypt. Thus, this so called “transplant tourism” has a great impact on the progress of the LDLT program in Egypt[26]. Significant effort is needed to establish a comprehensive legal system allowing deceased and living donor liver transplantation with airtight safeguards against donor coercion, commercialism and time-consuming meaningless obstacles[27].

In conclusion, dependence on LDLT is insufficient, especially in a country where HCV-induced liver cirrhosis is prevalent. Many strategies can be adopted to increase the living liver donor pool. Most, if not all, of these strategies have risks for the donor (older donors) or for the recipient (ABO incompatible LDLT and HBcAb positive donors). Legalization of DLT is essential to cope with the increasing number of patients in need of liver transplantation.

In this study, the authors investigated the impact of excluded living donors on patients, the transplant team and medical resources in Egypt which does not have a deceased donor liver transplantation program.

Apart from differences in the evaluation protocols between reports, some authors also excluded donors due to reasons related to the recipient in their study. The absence of uniform criteria for the presentation of data makes it difficult to compare our study with previous studies. The authors believe that this is the first study of a large number of potential donors from an area where there is no DLT program.

Authors reported a retrospective cohort study of excluded donors from potential living-donor for liver transplantation, using the right lobe graft during 8.5 years in Egypt. They suggested that living donor liver transplantation is not enough especially in a country where hepatitis C virus induced liver cirrhosis is prevalent, and that strategies to increase the donor pool may involve a risk on the marginal donor or on the recipient with ABO incompatibility and/or with HBcAb(+) donors. They also concluded that legalization of deceased donor for liver transplantation is required. A death concept is so different between countries, and we have respect for if when a deceased-donor will be legislated.

P- Reviewer: Ciccocioppo R, Greco L, Rodriguez-Peralvarez M, Takahashi T, Tomohide H, Topaloglu S, Wong RJ S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Ethics Committee of the Transplantation Society. The consensus statement of the Amsterdam Forum on the Care of the Live Kidney Donor. Transplantation. 2004;78:491-492. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Barr ML, Belghiti J, Villamil FG, Pomfret EA, Sutherland DS, Gruessner RW, Langnas AN, Delmonico FL. A report of the Vancouver Forum on the care of the live organ donor: lung, liver, pancreas, and intestine data and medical guidelines. Transplantation. 2006;81:1373-1385. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pruett TL, Tibell A, Alabdulkareem A, Bhandari M, Cronin DC, Dew MA, Dib-Kuri A, Gutmann T, Matas A, McMurdo L. The ethics statement of the Vancouver Forum on the live lung, liver, pancreas, and intestine donor. Transplantation. 2006;81:1386-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948. Available from: http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html. |

| 5. | Salah T, Sultan AM, Fathy OM, Elshobary MM, Elghawalby NA, Sultan A, Yassen AM, Elsarraf WM, Elmorshedi M, Elsaadany MF. Outcome of right hepatectomy for living liver donors: a single Egyptian center experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1181-1188. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Valentín-Gamazo C, Malagó M, Karliova M, Lutz JT, Frilling A, Nadalin S, Testa G, Ruehm SG, Erim Y, Paul A. Experience after the evaluation of 700 potential donors for living donor liver transplantation in a single center. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1087-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Araújo CC, Balbi E, Pacheco-Moreira LF, Enne M, Alves J, Fernandes R, Steinbrück K, Martinho JM. Evaluation of living donor liver transplantation: causes for exclusion. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:424-425. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Moreno Gonzalez E, Meneu Diaz JC, Garcia Garcia I, Loinaz Segurola C, Jimenez C, Gomez R, Abradelo M, Moreno Elola A, Jimenez S, Ferrero E. Live liver donation: a prospective analysis of exclusion criteria for healthy and potential donors. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1787-1790. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tsang LL, Chen CL, Huang TL, Chen TY, Wang CC, Ou HY, Lin LH, Cheng YF. Preoperative imaging evaluation of potential living liver donors: reasons for exclusion from donation in adult living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2460-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | 2006 Census. Cairo: Central Agency for Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) 2007; . |

| 11. | Pascher A, Sauer IM, Walter M, Lopez-Haeninnen E, Theruvath T, Spinelli A, Neuhaus R, Settmacher U, Mueller AR, Steinmueller T. Donor evaluation, donor risks, donor outcome, and donor quality of life in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:829-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haberal M, Emiroglu R, Boyactoğlu S, Demirhan B. Donor evaluation for living-donor liver transplantation. Transpl Proc. 2002;34:2145–2147. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pomfret EA, Pomposelli JJ, Gordon FD, Erbay N, Lyn Price L, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL. Liver regeneration and surgical outcome in donors of right-lobe liver grafts. Transplantation. 2003;76:5-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Marcos A. Right lobe living donor liver transplantation: a review. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:3-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hwang S, Lee SG, Lee YJ, Sung KB, Park KM, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Hwang GS, Kim KM. Lessons learned from 1,000 living donor liver transplantations in a single center: how to make living donations safe. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:920-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Trotter JF, Wisniewski KA, Terrault NA, Everhart JE, Kinkhabwala M, Weinrieb RM, Fair JH, Fisher RA, Koffron AJ, Saab S. Outcomes of donor evaluation in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2007;46:1476-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Egawa H, Teramukai S, Haga H, Tanabe M, Fukushima M, Shimazu M. Present status of ABO-incompatible living donor liver transplantation in Japan. Hepatology. 2008;47:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vikram R, Akira M, Toshimi K, Yasuhiro O, Iida T, Kazuyuki N, Naoya S, Kosuke E, Toshiyuki H, Shintaro Y. Splenectomy Does Not Offer Immunological Benefits in ABO-Incompatible Liver Transplantation With a Preoperative Rituximab. Transplantation. 2012;93:99-105. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lu H, Zhang CY, Ding W, Lu YJ, Li GQ, Zhang F, Lu L. Severe hepatic necrosis of unknown causes following ABO-incompatible liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:964-967. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Toso C, Al-Qahtani M, Alsaif FA, Bigam DL, Meeberg GA, James Shapiro AM, Bain VG, Kneteman NM. ABO-incompatible liver transplantation for critically ill adult patients. Transpl Int. 2007;20:675-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Troisi R, Noens L, Montalti R, Ricciardi S, Philippé J, Praet M, Conoscitore P, Centra M, de Hemptinne B. ABO-mismatch adult living donor liver transplantation using antigen-specific immunoadsorption and quadruple immunosuppression without splenectomy. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1412-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim HY, Choi JY, Park CH, Song MJ, Jang JW, Chang UI, Bae SH, Yoon SK, Han JY, Kim DG. Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Using Hepatitis B Core Antibody-Positive Grafts in Korea, a Hepatitis B-endemic Region. Gut Liver. 2011;5:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Muñoz SJ. Use of hepatitis B core antibody-positive donors for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:S82-S87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Avelino-Silva VI, D’Albuquerque LA, Bonazzi PR, Song AT, Miraglia JL, De Brito Neves A, Abdala E. Liver transplant from Anti-HBc-positive, HBsAg-negative donor into HBsAg-negative recipient: is it safe? A systematic review of the literature. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:735-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Guba M, Adcock L, MacLeod C, Cattral M, Greig P, Levy G, Grant D, Khalili K, McGilvray ID. Intraoperative ‘no go’ donor hepatectomies in living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:612-618. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Khalaf H, Farag S, El-Hussainy E. Long-term follow-up after liver transplantation in Egyptians transplanted abroad. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1931-1934. [PubMed] |

| 27. | El-Gazzaz GH, El-Elemi AH. Liver transplantation in Egypt from West to East. TRRM. 2010;2:41–46. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |