Published online Oct 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13591

Revised: March 23, 2014

Accepted: May 29, 2014

Published online: October 7, 2014

Processing time: 236 Days and 15.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the gastric emptying after bowel preparation to allow general anaesthesia.

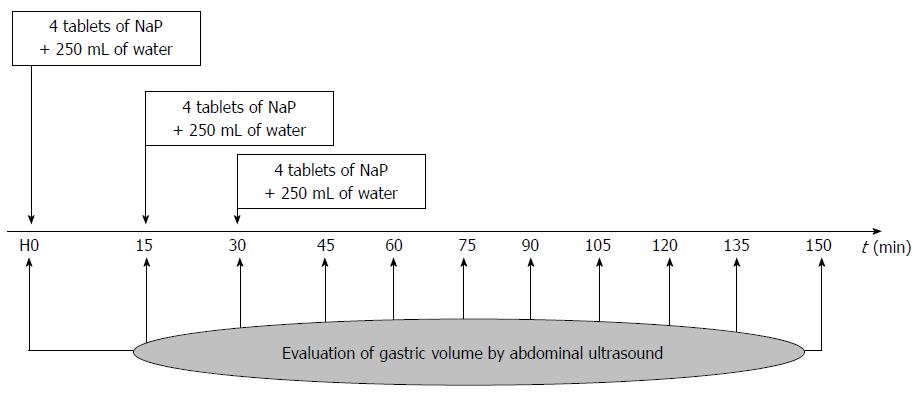

METHODS: A prospective, non-comparative, and non-randomized trial was performed and registered on Eudra CT database (2011-002953-80) and on www.trial.gov (NCT01398098). All patients had a validated indication for colonoscopy and a preparation using sodium phosphate (NaP) tablets. The day of the procedure, patients took 4 tablets with 250 mL of water every 15 min, three times. The gastric volume was estimated every 15 min from computed antral surfaces and weight according to the formula of Perlas et al (Anesthesiology, 2009). Colonoscopy was performed within the 6 h following the last intake.

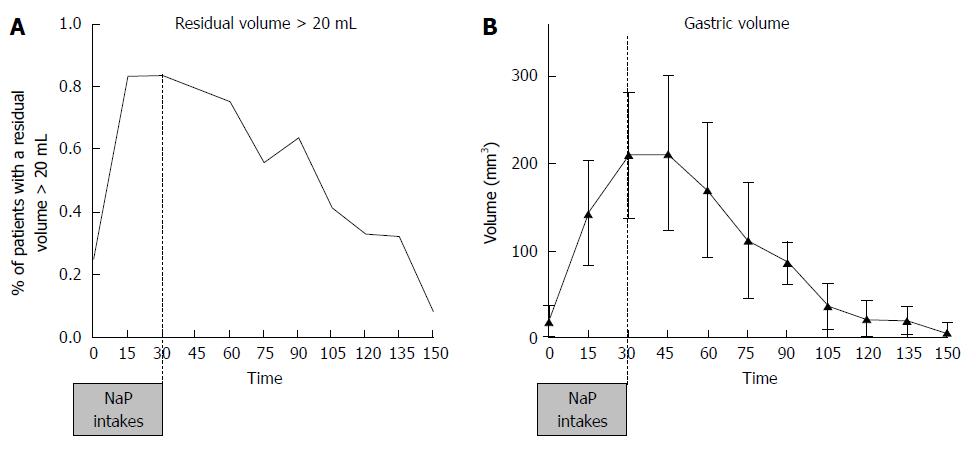

RESULTS: Thirty patients were prospectively included in the study from November 2011 to May 2012. The maximum volume of the antrum was 212 mL, achieved 15 min after the last intake. 24%, 67% and 92% of subjects had an antral volume below 20 mL at 60, 120 and 150 min, respectively. 81% of patients had a Boston score equal to 2 or 3 in each colonic segment. No adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were reported.

CONCLUSION: Gastric volume evaluation appeared to be a simple and reliable method for the assessment of gastric emptying. Data allow considering the NaP tablets bowel preparation in the morning of the procedure and confirming that gastric emptying is achieved after two hours, allowing general anaesthesia.

Core tip: Gastric emptying have never been evaluate prior colonoscopy. An evaluation by ultrasound prior colonoscopy appeared has an easy tool to identify complete gastric emptying and will allow anesthesiologist to perform sedation.

- Citation: Coriat R, Polin V, Oudjit A, Henri F, Dhooge M, Leblanc S, Delchambre C, Esch A, Tabouret T, Barret M, Prat F, Chaussade S. Gastric emptying evaluation by ultrasound prior colonoscopy: An easy tool following bowel preparation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(37): 13591-13598

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i37/13591.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13591

Colonoscopy is the gold standard procedure for the detection of polyps and colorectal carcinoma. Bowel preparation is a key factor of high quality colonoscopy[1]. Historically, bowel-cleansing methods consisted of dietary restrictions, oral cathartics and additional cathartic enemas[2]. These preparations have been considered to be effective for colonic cleansing for colonoscopy[3]. Despite their proven efficacy, recent data identified a lack of oral intake in patients resulting in up to 10% of patients requiring repeat colonoscopy due to insufficient bowel preparation[1]. Consensus recommendations on bowel preparation have been made[4] and identified that with polyethylene glycol (PEG) up to 15% of patients did not complete the preparation because of poor palatability and/or large volumes to be ingested[5,6].

In the recent years, new colon cleansing preparations have been developed to give an alternative to 4 L of PEG. The most commonly used are osmotic laxatives, which include sodium phosphate tablets[2]. They act by increasing colon water content by attracting extracellular fluid efflux through the bowel wall. Commercially available preparations with sodium phosphate are given in two doses of tablets or bottles over at least 6-12 h. The second dose is taken at least 4 h before the colonoscopy.

Anaesthetists require the final dose to be consumed at least 4 h in advance to prevent aspiration pneumonia during general sedation[7]. In western countries colonoscopies are performed using propofol sedation which does not influence gastric emptying[8]. Fasting by reducing the residual volume of food or liquid within the stomach is thought to reduce the risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric contents during a procedure[7]. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing fasting times of 2-4 h vs more than 4 h, report smaller gastric volumes in patients given clear liquids 2-4 h before a procedure[9]. The gastric residual volume is reduced to approximately 20 mL following a 2 h fast and is not reduced further by an additional 10 h of fasting[10]. The ASA guidelines indicate that patients should fast a minimum of 2 h for clear liquids and 6 h for a light meal prior to sedation[9]. Therefore, we explored the gastric emptying in patients over time receiving sodium phosphate tablets prior to colonoscopy.

A prospective, non-comparative, non-randomized open label trial was performed. Full ethical approval for the study was obtained from the local institutional review board. The study was approved by an Independent Ethics Committee, (CPP “Ile-de-France III”), the French competent health authorities (the AFSSAPS, “Agence française de sécurité sanitaire du médicament et des produits de santé’’, which became Agence Nationale de Securité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé, ANSM) and was registered on EUDRA CT database (Eudra CT 2011-002953-80) and on http://www.trial.gov (NCT01398098).

Patients undergoing total colonoscopy for screening or surveillance colonoscopy from November 2011 to May 2012 were selected for inclusion in the study. Signed informed consent was always required before any study procedure. All patients included in the study were aged from 18 to 75 years, scheduled as outpatient for a colonoscopy, able to swallow tablets and presented no contraindication for sodium phosphate such as renal failure or inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy, allergy or hypersensitivity to the product or to one of its excipient, nausea, recurrent vomiting, abdominal pain, diabetes mellitus (insulin-dependent or non-insulin dependent) or an history of gastric surgery. The study size was limited to thirty patients to confirm the feasability of the technique.

All patients received 32 tablets of sodium phosphate bowel preparation (NaP, Colokit©) in total before colonoscopy. Each tablet contains monobasic monohydrate sodium phosphate (1102 mg) and dibasic anhydrous sodium phosphate (398 mg). Preparation was standardized as following: The day before the examination, intakes were restricted to a light, low-fibre breakfast (tea or coffee with or without sugar, light rusk-like toast, butter or similar spread, jam, marmalade or honey). After midday, only clear liquids were allowed (water, clear soup, diluted fruit juice, black tea or coffee, clear fizzy or still soft drinks). In addition, the evening before the examination, patients had to take four NaP tablets with 250 mL of water (or another clear liquid) every 15 min, repeated a further 4 times for a total of 20 tablets. On the day of the examination, patients were hospitalized in the outpatient unit for the second phase of the colon preparation with a 4 tablets of NaP intake every 15 min, in addition to 250 mL of water (or another clear liquid), repeated another two times under the same conditions, i.e.,12 tablets in total.

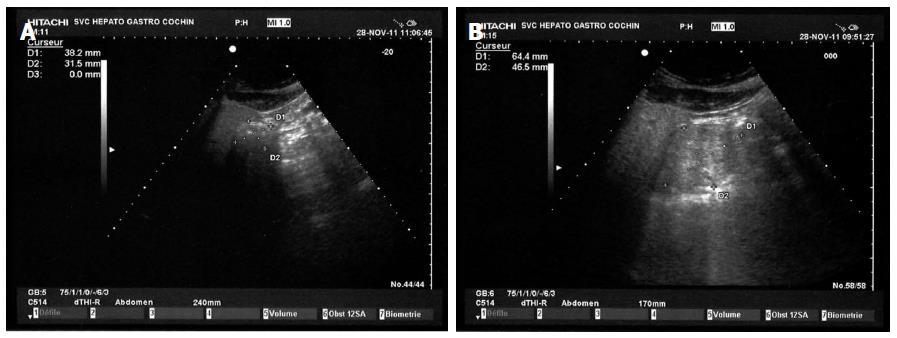

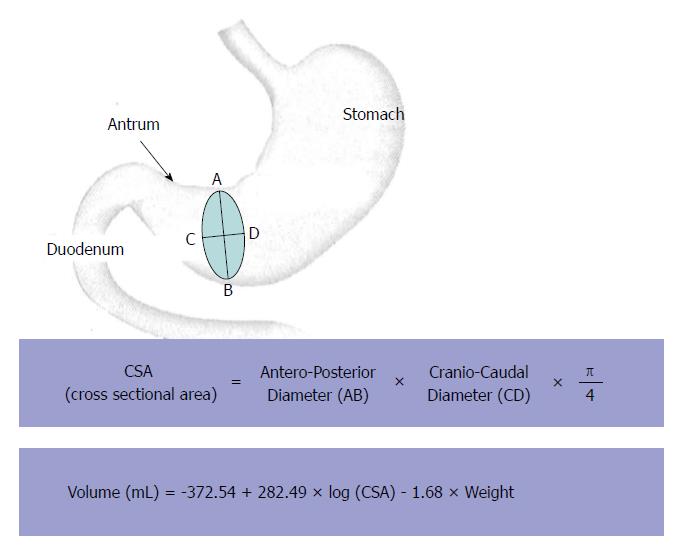

Measurement of gastric emptying was performed by antral diameters measurements using a digital abdominal ultrasound scanner as previously published[11]. Briefly, ultrasonographic views of the antrum were obtained using a sixth generation electronic convex probe (Hitachi Medical Systems, Platform Concept 5500) with transmission frequency (2.5-5 MHz) and high bandwidth (2-6 MHz). Images were obtained between peristaltic contractions with the stomach at rest prior to oral intake and every 15 min for 150 min (Figure 1). The antrum was imaged in a parasagittal plane of the epigastric area in patients in the right lateral decubitus position (Figure 2). Three measurements were performed at each time for the quantitative evaluation of the study. The cross sectional area (CSA) of the antrum was calculated according to the formula previously used by Bolondi et al[12] using two maximum perpendicular diameters representing the surface area of an ellipse (Figure 3). The antral cross-sectional area is linearly correlated with the gastric volume up to 300 mL; hence it is a reliable and reproducible method to study gastric emptying[11]. The principal parameter was the percentage of subjects with antral residual volume less or equal to 20 mL, which defines an empty stomach, at different times after the second sequence of NaP intake.

All explorations were performed with a Fujinon EC530WM colonoscope by trained endoscopists. Endoscopies were performed using total intravenous anesthesia with propofol. A colonoscopy was defined as incomplete when there was no visualization of anatomic features, such as the ileocecal valve, appendiceal orifice, ileocolonic anastomosis or terminal ileum, as previously described[13]. The good quality of bowel preparation was defined as a global Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) score ≥ 7, as previously published[14].

Descriptive statistics (group size, mean, standard deviations, median, ranges, and 95%CI) were used to report patients’ baseline characteristics. The analyses of primary and secondary objectives were conducted on the intention to treat (ITT) population. Comparisons between ultrasonographic examinations were performed by the Fisher exact test, the χ2 test with Yates correction, or the Wilcoxon test when appropriate. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Thirty patients were included in the present study while three subjects were excluded from the ITT population (ITT, n = 27) - two subjects were not exposed to the drug and failed to complete the course of tablets. Patients’ characteristics are included in Table 1. Reasons for colonoscopy included a personal history of polyps (44%), anaemia or a gastrointestinal bleeding (22%), and a family history of colorectal cancer (19%). Patients were also taking medications for diseases of the cardiovascular system (41%), the alimentary tract (22%) and the nervous system (18%). The median time between the first intake and the beginning of the second sequence was 16.3 h (range: 11.9-18.7 h). The mean time between the last intake of NaP tablets and the procedure was 4.1 ± 1.0 h.

| Total, n = 27 | |

| Age (yr) | |

| Median (Min - Max) | 51 (31-73) |

| Gender | |

| Male/Female (%) | 56/44 |

| Weight (kg) | |

| Median (Min - Max) | 73 (48-110) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m²) | |

| Median (Min - Max) | 25.1 (20.2-34.7) |

| < 18.5 kg/m² | 0 |

| 18.5-25 kg/m² | 13 |

| 25-30 kg/m² | 13 |

| > 30 kg/m² | 1 |

| Smoking status (%) | |

| Never smoke | 33 |

| Former smoker | 38 |

| Smoker | 29 |

| Preparation quality1 (%) | |

| Excellent (score = 8/9) | 50 |

| Good (score = 7) | 15.4 |

| Medium (score = 6) | 19.2 |

| Insufficient (score ≤ 5) | 15.4 |

| Caecal Intubation (%) | 100 |

| Colonoscopy results (%) | |

| Normal colonoscopy | 14.8 |

| Polyps | 78.3 |

| Diverticula | 26.1 |

| Ulcerations | 8.7 |

| Others anomalies | 30.4 |

| Number of detected sessile and/or Flat plans polyps which were detected | |

| Right colon | 55 |

| Transverse colon | 11 |

| Left colon and rectum | 29 |

The acceptability of the preparation was high as 93% and 100% of the patients considered the intake of the 32 tablets and the total quantity of liquid easy to take, respectively. The good quality of bowel preparation, defined as BBPS score ≥ 7, was obtained for more than 65% of the subjects and an insufficient preparation was observed in 15% (Table 1). 81% of subjects had a BBPS score ≥ 2 in each segment. There was no need for additional cleaning for approximately two-third of subjects (70%). The mean duration of the colonoscopy was 33.1 ± 8.7 min. The mean time of withdrawal was 15.9 ± 4.4 min. All colonoscopies reached the caecum and anomalies, mainly polyps, were found in 85% of patients (Table 1).

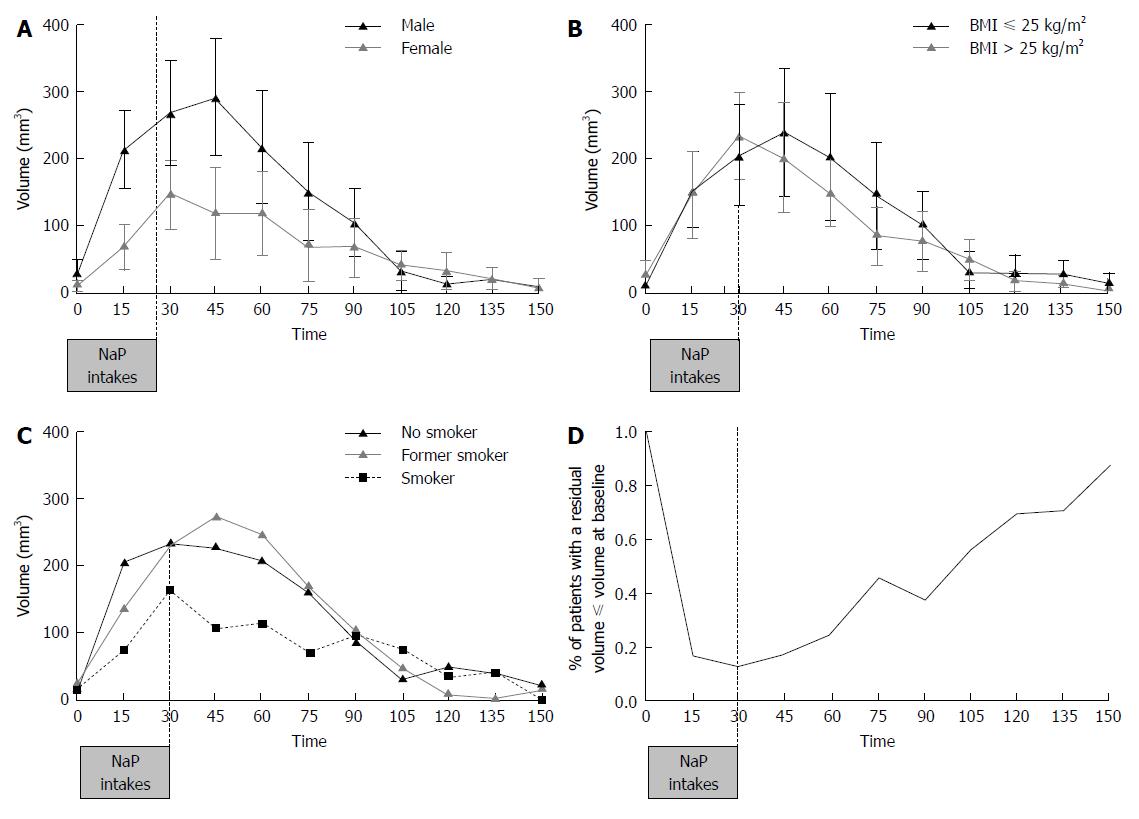

Patients with an antral volume less than or equal to 20 mL increased from 12% at 30 min, corresponding to the last intake, to 92% at 150 min (Figure 4A). Thirty minutes after the last intake of 4 NaP tablets (60 min time), 24% of patients had an antral volume lower or equal to 20 mL. The mean antrum volume at 0 min was 18.8 ± 18.2 mL. The antral volume increased until 45 min, reaching a peak of 212.0 ± 89.1 mL, and subsequently decreasing. From 120 min (90 min after the last intake) volume values are close to the threshold value of 20 mL (Mean: 22.7 ± 21.6 mL; Figure 4B). Male subjects tended to have a 1.5 to 3 times greater antral volume than female subjects between time 0 and 90 min (Figure 5A). At 45 min, antral volume in males was significantly higher than in females (291.2 ± 87.0 mL vs 118.5 ± 68.8 mL, P < 0.001). Subjects with BMI lower or equal to 25 kg/m² tended to have a slightly greater antral volume from 45 min until 90 min than overweight subjects but off note there was no difference after 90 min (Figure 5B). Non-smokers tended to have a non-significant lower antral volume than former smokers and smokers from 0 to 90 min (Figure 5C). Residual antral volume at 120 min also tended to become lower or equal to antral volume at baseline (22.7 ± 21.6 mL vs 18.8 ± 18.2 mL, P = 0.15). At 105 min, more than half of patients (57%) had a residual volume lower or equal to their value at baseline. This proportion constantly increased up to 87% at 150 min (Figure 5D). Data recorded during the study did not highlight particular safety concerns, and no adverse events requiring to treatment discontinuation were reported.

Our study reports for the first time the feasibility of gastric emptying evaluation in patients undergoing colonoscopy. The ultrasound evaluation of the antral volume will help physicians and anaesthetists to confirm the total gastric emptying and therefore reduces the risk of interstitial pneumonitis.

Colonic lavage using a specific laxative in addition to a light diet and water for 24 h on the day preceding the investigation are advised to ensure colonic cleanliness, guaranteeing quality of bowel preparation. In western countries, colonoscopy is mainly performed under general anesthesia using propofol, hence subjects should be fasting to avoid the risk of bronchial aspiration syndrome. A fasting period of at least 6 h is recommended for the ingestion of a solid meal. The ASA guidelines confirms by recommending a 6 h fasting even for light meal prior to sedation and authorizes to reduce the period to 2 h for clear liquids[9].

In addition our study confirms the efficacy of NaP tablets for colonoscopy cleansing. Gastric scintigraphy had become the reference technique for gastric emptying evaluation but has the disadvantage of irradiation, cost, limited availability of gamma cameras, the need for radioactive labels, and many sources of error. Gastric emptying assessed by scintigraphy were therefore not possible in current practice. Meanwhile, the study of Benini et al[15] in solid meal confirms that ultrasound is as good as scintigraphy for the measurement of gastric emptying. Perlas et al[11] previously identified the bedside two-dimensional ultrasonography as a useful non-invasive tool to determine gastric content and gastric volume. In their study, subjects were scanned either after 8 h of fasting, after intake of up to 500 mL plus effervescent powder, or after a standardized solid meal. Our study reinforced the feasibility of the bedside ultrasound to evaluate the gastric emptying before colonoscopy and identified a 25% gastric emptying at 60 min rising to 70% at 120 min and 87% at 150 min. Recently, the ultrasound technique was validated in patients undergoing elective surgery and reinforced the feasibility of this technique to identify the absence of residual gastric fluid at the time of anaesthetic induction[16]. Considering the lack of toxicity of the bedside ultrasound and the feasibility of the technique, ultrasound evaluation appears to be a useful technique to confirm gastric emptying prior sedation.

So far, there is no definitive standard method for the preoperative determination of gastric contents volume. Studies have shown that measuring the aspirated gastric contents to determine the gastric contents volume is an option[17]. Considering this Bouvet et al[18] identified that the aspirated volume of fluid gastric contents was close to the current total fluid volume in the stomach and a positive relationship between antral CSA and volume of aspirated gastric contents was made. Meanwhile, Bouvet et al[18] identified a better correlation between CSA and volume in patients moved to the right lateral decubitus position. In addition, Perlas et al[11] set the threshold of volume at 52 mL which corresponds to the upper limit of a negligible fluid volume within normal expected ranges for fasted patients. These considerations led us to study two thresholds in our study: a “severe” (20 mL) threshold value, and the broader indicated by Perlas et al[11]. In our study, results didn’t differ from a residual value of 20 mL than 52 mL. At 45 min, 21% and 25% of patients had a residual volume below 20 mL or 52 mL, respectively. At 120 min, 67% and 87% of patients had a residual volume below 20 mL or 52 mL. An easy-to-use bedside tool to reliably assess the nature and volume of gastric contents such as ultrasound may therefore be very useful because of its simple implementation, its non-invasive and inexpensive nature.

In the present study, we identified no modification of gastric emptying between patients considering BMI and smoking activity. Patients with BMI lower or equal to 25 kg/m² have no significant differences of gastric emptying compare to patients with BMI above 25 (Figure 5B). In the other hand, a delayed of gastric emptying have been identify in obese patients[19]. In our study, no obese patients (BMI > 30 kg/m²) were included and diabetes was considered as non-inclusion criteria. Those two points may explain the trend of gastric emptying in patients from 25 to 30 kg/m² compare to normal BMI patients. In our study, non-smokers tended to have a lower gastric volume in line with a higher gastric emptying than former smokers and smokers. It has been identified that smoking delays gastric emptying of solids, but not liquids[20]. In our study, patients’ intake are pills for a total number of 32 and water, which may explain the tendency to a higher gastric emptying observed in non-smokers.

In the past decade, the colonoscopy procedure has been largely studied to improve colorectal lesions detection resulting in the identification of quality indicators for colonoscopy procedure[1]. Despite the technique required by the operator for colonoscopy, the success depends upon a number of factors including correct cecum intubation, cleaning of the colon, careful mucosal inspection, and operator experience[21]. With the rapidly rising costs of healthcare and the need to rationalize spending, it is important to spare costly repeat procedures, as in the cases of incomplete colonoscopy[1,22]. In our study all patients had a complete colonoscopy with a good overall cleansing preparation. Regarding preparations for colonic cleansing, NaP seems to have a sufficient efficacy with more than 80% of the patients with a satisfactory BBPS. In a prior study, adequate cleansing of the colon occurs in up to 80% with 4 L of PEG[1]. In an outpatient setting and in patients without contraindication to NaP tablets, NaP appears to be a feasable and effective alternative to 4 L of PEG. In addition, patients acceptability was good with up to 93% of the patients who considered the intake of the 32 NaP tablets easy to be taken. Colonoscopy demand should be expected to increase significantly in Europe over the next few years because of ongoing or planned colorectal carcinoma screening campaigns and colonoscopic surveillance program[2]. Bowel preparation is essential for both the quality of the colonoscopy and the adenoma or adenocarcinoma detection rate[1,21,23]. Aqueous sodium phosphate formulations are low volume hyperosmotic solutions and draw water osmotically from intestinal tissues into the bowel lumen[2]. The NaP tablets are validated and commercialy available in France as in western countries for bowel preparation. Our study reinforced the use of NaP tablets for colon cleansing even in the two hours following the last intake. Our data confirm the option of using NaP tablets in patients undergoing colonoscopy in an outpatient setting.

Our study has some limitations. Firstly, the diagnostic tool extrapolates antral gastric volume from the antral area; it requires additional development and a larger validation, with independent methods to measure gastric volume. Also, the BMI of subjects in this relatively small study was measured between 20.2 and 34.7 kg/m2, and most of the subjects were in the “normal” to “overweight” subgroups. The results may not be extrapolated to patients with obesity, as the quality of ultrasound images may be more problematic. The easy-to-use bedside ultrasound deserves an evaluation in this particular situation, as in diabetic patients. Despite those limitations, our preliminary results deserve to be validated in a larger study to confirm the usefulness of ultrasound evaluation for both the physicians and the anesthesiologists.

To conclude, gastric volume measured by extrapolation of antral ultrasound area assessment was a simple and reliable method for the assessment of gastric emptying. Respectively, 67% and 92% of subjects had gastric emptying with an antral volume below 20 mL at 120 and 150 min after the last intake of NaP tablets as bowel preparation.

Gastric volume evaluated by ultrasound is validated for the measurement of total gastric emptying. In the present study, we investigated the gastric emptying after bowel preparation to allow general anaesthesia.

Bowel preparation is a key factor of high quality colonoscopy. Gastric emptying is necessary to allow general anaesthesia.

This study reports for the feasibility of gastric emptying evaluation in patients undergoing colonoscopy. The ultrasound evaluation of the antral volume will help physicians and anaesthetists to confirm the total gastric emptying and therefore reduces the risk of interstitial pneumonitis.

Gastric emptying evaluation using ultrasonography helps the physicians to verify the lack of bowel preparation in the stomach. Its evaluation would help both the anaesthesiologist before general anaesthesia and the gastroenterologist before colonoscopy.

Gastric emptying is performed by antral diameters measurements using a digital abdominal ultrasound scanner. The antrum was imaged in a parasagittal plane of the epigastric area in patients in the right lateral decubitus position. Gastric emptying is correlated with the overall gastric volume.

This is a brief prospective, non-comparative and non-randomized clinical trial. It could be published in the journal. The manuscript entitled “Gastric emptying evaluation by ultrasound prior colonoscopy: an easy tool following bowel preparation” employed thirty patients to conduct a prospective, non-comparative, and non-randomized trial and to evaluate gastric volume measured by ultrasound as the measurement of total gastric emptying. They found that gastric volume evaluation appears to be a simple and reliable method for the assessment of gastric emptying.

P- Reviewer: Gong Y S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Coriat R, Lecler A, Lamarque D, Deyra J, Roche H, Nizou C, Berretta O, Mesnard B, Bouygues M, Soupison A. Quality indicators for colonoscopy procedures: a prospective multicentre method for endoscopy units. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parente F, Marino B, Crosta C. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy in the era of mass screening for colo-rectal cancer: a practical approach. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:87-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | DiPalma JA, Brady CE, Stewart DL, Karlin DA, McKinney MK, Clement DJ, Coleman TW, Pierson WP. Comparison of colon cleansing methods in preparation for colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:856-860. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Golub RW, Kerner BA, Wise WE, Meesig DM, Hartmann RF, Khanduja KS, Aguilar PS. Colonoscopic bowel preparations--which one? A blinded, prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:594-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marshall JB, Pineda JJ, Barthel JS, King PD. Prospective, randomized trial comparing sodium phosphate solution with polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:631-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cooper GS, Kou TD, Rex DK. Complications following colonoscopy with anesthesia assistance: a population-based analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:551-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Hammas B, Hvarfner A, Thörn SE, Wattwil M. Propofol sedation and gastric emptying in volunteers. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1998;42:102-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:495-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 631] [Cited by in RCA: 510] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cohen LB, Ladas SD, Vargo JJ, Paspatis GA, Bjorkman DJ, Van der Linden P, Axon AT, Axon AE, Bamias G, Despott E. Sedation in digestive endoscopy: the Athens international position statements. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:425-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Perlas A, Chan VW, Lupu CM, Mitsakakis N, Hanbidge A. Ultrasound assessment of gastric content and volume. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:82-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bolondi L, Bortolotti M, Santi V, Calletti T, Gaiani S, Labò G. Measurement of gastric emptying time by real-time ultrasonography. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:752-759. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Neerincx M, Terhaar sive Droste JS, Mulder CJ, Räkers M, Bartelsman JF, Loffeld RJ, Tuynman HA, Brohet RM, van der Hulst RW. Colonic work-up after incomplete colonoscopy: significant new findings during follow-up. Endoscopy. 2010;42:730-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 925] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Benini L, Sembenini C, Heading RC, Giorgetti PG, Montemezzi S, Zamboni M, Di Benedetto P, Brighenti F, Vantini I. Simultaneous measurement of gastric emptying of a solid meal by ultrasound and by scintigraphy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2861-2865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Perlas A, Davis L, Khan M, Mitsakakis N, Chan VW. Gastric sonography in the fasted surgical patient: a prospective descriptive study. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:93-97. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Hardy JF, Plourde G, Lebrun M, Côté C, Dubé S, Lepage Y. Determining gastric contents during general anaesthesia: evaluation of two methods. Can J Anaesth. 1987;34:474-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bouvet L, Mazoit JX, Chassard D, Allaouchiche B, Boselli E, Benhamou D. Clinical assessment of the ultrasonographic measurement of antral area for estimating preoperative gastric content and volume. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1086-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jackson SJ, Leahy FE, McGowan AA, Bluck LJ, Coward WA, Jebb SA. Delayed gastric emptying in the obese: an assessment using the non-invasive (13)C-octanoic acid breath test. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2004;6:264-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Miller G, Palmer KR, Smith B, Ferrington C, Merrick MV. Smoking delays gastric emptying of solids. Gut. 1989;30:50-53. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Rex DK. Maximizing detection of adenomas and cancers during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2866-2877. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Coriat R, Lecler A, Cassaz C, Roche H, Podevin P, Mesnard B, Berretta O, Nizou C, Sautereau D, Bouygues M. Évaluation des pratiques professionnelles en endoscopie: étude multicentrique de faisabilité d’une méthode simple et reproductible d’évaluation de la qualité de la coloscopie dans des structures privées et publiques. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:175. |

| 23. | de Jonge V, Sint Nicolaas J, Cahen DL, Moolenaar W, Ouwendijk RJ, Tang TJ, van Tilburg AJ, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME. Quality evaluation of colonoscopy reporting and colonoscopy performance in daily clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:98-106. [PubMed] |