Published online Sep 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12668

Revised: May 6, 2014

Accepted: May 25, 2014

Published online: September 21, 2014

Processing time: 211 Days and 21.6 Hours

Gastric artery aneurysm is a rare and lethal condition, and is caused by inflammatory or degenerative vasculopathies. We describe herein the clinical course of a patient with a ruptured gastric artery aneurysm associated with microscopic polyangiitis. Absence of vasculitic changes in the aneurysm resected and negative results of autoantibodies interfered with our diagnostic process. We should have adopted an interventional radiology and initiated steroid therapy promptly to rescue the patient.

Core tip: Gastric artery aneurysm is a rare and lethal condition. Segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM), one of major causes of the aneurysm, has been recognized to be distinguished from inflammatory arteriopathies because of a difference in therapeutic strategy. However, as the present case indicates, SAM may not be an independent disease entity but a morphological alteration associated with diverse vascular damages.

- Citation: Ikura Y, Kadota T, Watanabe S, Arimoto A, Nishioka E. Ruptured gastric artery aneurysm: An uncommon manifestation of microscopic polyangiitis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(35): 12668-12672

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i35/12668.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i35.12668

Gastric artery aneurysm, which often ruptures at initial presentation, is a rare and lethal condition[1,2]. Stanley et al[2] reported that gastric or gastroepiploic artery aneurysms accounted for only 4% of all splanchnic artery aneurysms. Surgical removal of affected vessels and interventional radiology (IVR) are treatments that are currently available for ruptured cases[1-3]. Although its etiology is diverse and difficult to be specified, a prompt and correct diagnosis is necessary to rescue patients. Several factors contribute to aneurysm formation. Especially vasculitis and degenerative vasculopathy have been recognized to play the most substantial role in the development of the aneurysm[2].

Here we present an autopsy case of gastric artery aneurysm. A background disorder was microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), which could not be diagnosed clinically because of unfortunate accumulation of diagnostic difficulties.

A 76-year-old man was transported to our hospital by ambulance because of severe abdominal pain that suddenly occurred at dinnertime. The patient had a long medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and atrial fibrillation. There was no family history of autoimmune disease. On admission, he was alert and appeared to be in distress. Vital signs included a temperature of 36.3 °C, pulse of 86 beats per minute, blood pressure of 144/114 mmHg, and respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. Physical examination revealed that his abdomen was flat, and abdominal tenderness was localized to the right upper quadrant. No abdominal tumor was palpable. Bowel sound was weak.

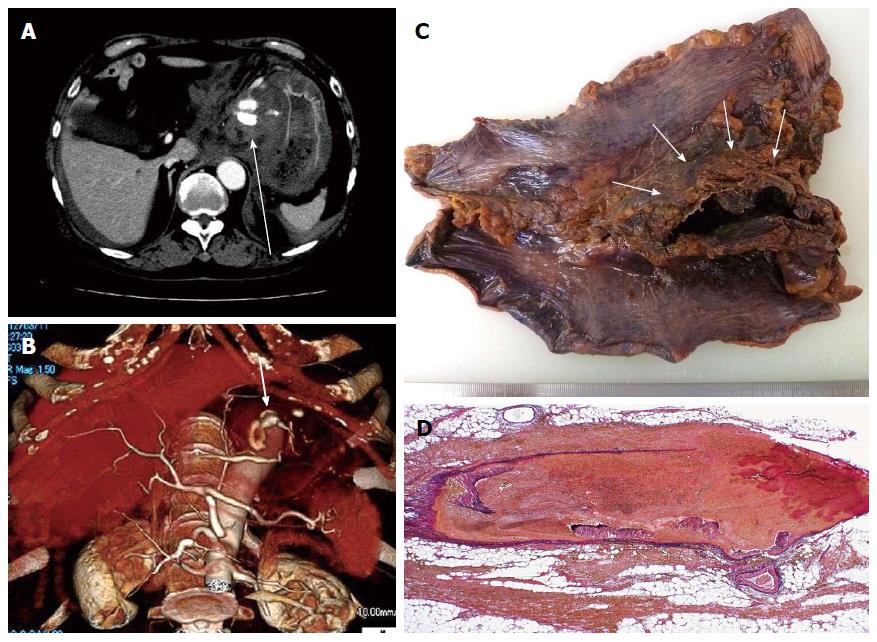

Laboratory test results (Table 1) indicated leukocytosis and hyperglycemia. Electrocardiography revealed atrial fibrillation, but no other critical changes were found. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a hematoma of approximately 60 mm in diameter, containing a dilated abnormal vessel in the lesser omentum (Figure 1A). CT angiography further revealed influx of the left gastric artery into this abnormal vasculature (Figure 1B). The physician diagnosed his condition as ruptured gastric artery aneurysm, and exploratory laparotomy was performed emergently.

| Variable | Normal value | Inpatient result |

| White blood cell count, cells/mm3 | 4500-8000 | 137001 |

| Differential cell count, % | ||

| Neutrophils | 28-72 | 821 |

| Lymphocytes | 18-58 | 141 |

| Monocytes | 0-7 | 3 |

| Red blood cell count, cells/mm3 | 4100000-5300000 | 4010000 |

| Hemoglobin, mg/dL | 14-18 | 11.91 |

| Hematocrit, % | 40-48 | 36.11 |

| Platelet count, platelets/mm3 | 130000-350000 | 1570000 |

| International normalized ratio | ≤ 1.2 | 3.531 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 31-47 | 40 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 65-110 | 3171 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 4.3-5.8 | 6.61 |

| Sodium, mEq/L | 135-147 | 144 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 3.3-4.8 | 4.2 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 22-26 | 18.01 |

| Urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 8-20 | 8.2 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.44-1.15 | 1.13 |

| Creatine kinase, U/L | 24-195 | 96 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.2-1.0 | 1.0 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 3.8-5.3 | 3.71 |

| Total protein, mg/dL | 6.7-8.3 | 5.71 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 8-38 | 26 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 4-44 | 23 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, U/L | 6-88 | 41 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 104-338 | 213 |

| Amylase, U/L | 41-110 | 55 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 106-211 | 200 |

| C-reactive protein level, mg/L | < 3.0 | 3.51 |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis C virus antibody | Negative | Negative |

At laparotomy, surgeons confirmed the hematoma in the lesser omentum (Figure 1C). Marked subserosal hemorrhage was also seen in the stomach. The aneurysm was not found, since it was probably encased in the hematoma. Total gastrectomy was chosen intraoperatively to rescue the patient. The surgical specimen was examined pathologically, and a ruptured fusiform aneurysm was found inside the hematoma as expected (Figure 1D). The aneurysm appeared to have developed by arterial wall dissection, and an identical change was observed in most of the medium-sized arteries surrounding the stomach. The vascular lesion resembled segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM)[4-7]. Inflammatory vascular damage was not observed in the affected vessel.

Postoperative infectious events disturbed the patient’s recovery. Furthermore, diabetes insipidus of undeterminable etiology was of concern to the physicians. Seven weeks after surgery, hematemesis, purpura and hematuria developed. Cutaneous biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Although autoantibodies including perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) were negative (Table 2), steroid therapy was instituted since generalized vasculitic disorder was strongly suspected. While purpura was attenuated, renal function deteriorated. Steroid therapy was discontinued because no further efficacy was expected. The downhill clinical course led to the patient’s death due to sepsis.

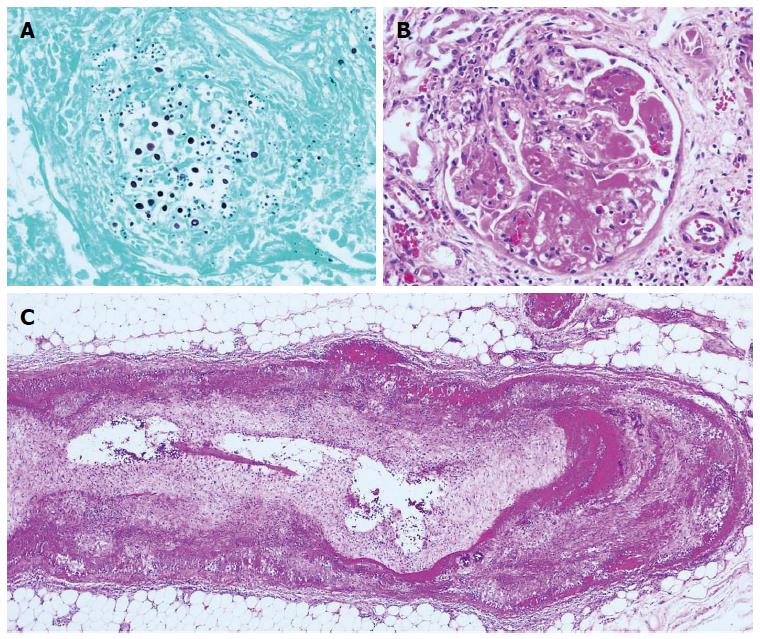

Autopsy was performed and disclosed systemic cryptococcosis (Figure 2A) and necrotizing vasculitis. The affected vessels varied in size from arterioles of renal glomeruli (Figure 2B) to medium-sized arteries of abdominal organs (Figure 2C). The final pathologic diagnosis was MPA. Gastric artery aneurysm, diabetes insipidus and purpura that developed during the hospitalization were each considered to be manifestations of this systemic vasculitic disorder.

The most critical point in this case was whether the primary vascular disorder was vasculitis or degenerative vasculopathy.

A previous report suggested that unrecognized splanchnic artery aneurysms are caused mostly by SAM[7]. Slavin et al[4] proposed the concept of SAM as an independent disease entity and insisted on its importance as a cause of splanchnic artery aneurysms. SAM is a degenerative vasculopathy that leads to segmental myolysis in the media of medium-sized arteries and is often accompanied by aneurysm formation in affected vessels[4,5]. In the present case, the histopathologic findings of the surgical specimen (Figure 1D) were consistent with SAM: segmental myolysis in the media of medium-sized arteries and tiny remnants of damaged media called medial islands were observed[4-7]. Thus we could not exclude SAM from the differential diagnoses, even after the development of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Next we considered the possibility of classic polyarteritis nodosa (cPN). cPN is the prototype of inflammatory medium-sized arteriopathies. Elderly males are prone to be affected. It can affect medium-sized arteries in any portion of the body, and can lead to the development of arterial dissection like in our case. However, fibrinoid necrosis, a morphological hallmark of cPN, was not seen in the affected gastric artery, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis could not be explained by cPN.

The final pathologic diagnosis was MPA. MPA is a pANCA-related immunological disorder, and patients with MPA show necrotizing vasculitis principally in capillaries, arterioles and venules[8,9]. Kidneys, skin and the gastrointestinal tract are often involved, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis can occur as a cutaneous manifestation. As well as cPN, MPA occasionally affects medium-sized arteries and induces the development of aneurysms[10-12].

It was very difficult to make a diagnosis of MPA because pANCA was negative and no necrotizing vasculitis was found in the surgical specimen. However, a considerable number of patients with MPA are negative for pANCA[8,9]. Moreover, SAM-like vascular lesions have been reported to be formed in a patient with diverse types of vasculitis[13,14]. We should have first considered a possibility of vasculitis-related aneurysm, and should have promptly instituted a steroid therapy. Renal biopsy, which is recognized to be useful in the diagnosis of MPA (i.e., pauci-immune necrotizing glomerulonephritis), might have provided a clue to the differential diagnosis[9].

Patients with a ruptured splanchnic artery aneurysm mostly need surgical intervention or IVR to save their lives[1-3]. In the status of shock, the risk associated with surgery is extremely high, and thus, IVR is currently recommended as a first-line therapy[15]. Indeed, since IVR was introduced to treat ruptured aneurysm, therapeutic outcomes have been improving[3]. We might have rescued the patient if we had chosen IVR and instituted timely steroid therapy.

The patient reported sudden-onset of severe abdominal pain.

A gastric artery aneurysm was formed as a result of inflammatory or degenerative vasculopathy.

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis having arisen postoperatively suggested that the patient had rather a vasculitic disorder than a degenerative vasculopathy.

Vasculitis was strongly suspected, but autoantibodies including perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody were negative.

Abdominal computed tomography revealed a hematoma and an abnormally dilated vessel in the lesser omentum.

The gastric artery aneurysm was formed in association with segmental arterial medialysis (SAM)-like changes, and ruptured.

Steroid therapy was initiated seven weeks after surgery.

Any type of vasculitis can lead to aneurysm formation in association with SAM-like vascular changes.

Cases like this one are important because it represents a diagnostic challenge.

P- Reviewer: Higuera-de la Tijera M, Takahashi T S- Editor: Nan J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Stanley JC, Thompson NW, Fry WJ. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1970;101:689-697. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Stanley JC, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, Whitehouse WM, Zelenock GB, Lindenauer SM. Clinical importance and management of splanchnic artery aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1986;3:836-840. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Murata S, Tajima H, Abe Y, Watari J, Uchiyama F, Niggemann P, Kumazaki T. Successful embolization of the left gastric artery aneurysm obtained in preoperative diagnosis: a report of 2 cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1895-1897. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Slavin RE, Gonzalez-Vitale JC. Segmental mediolytic arteritis: a clinical pathologic study. Lab Invest. 1976;35:23-29. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Slavin RE, Cafferty L, Cartwright J. Segmental mediolytic arteritis. A clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of two cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:558-568. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Inayama Y, Kitamura H, Kitamura H, Tobe M, Kanisawa M. Segmental mediolytic arteritis. Clinicopathologic study and three-dimensional analysis. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1992;42:201-209. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Inada K, Maeda M, Ikeda T. Segmental arterial mediolysis: unrecognized cases culled from cases of ruptured aneurysm of abdominal visceral arteries reported in the Japanese literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203:771-778. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Guillevin L, Durand-Gasselin B, Cevallos R, Gayraud M, Lhote F, Callard P, Amouroux J, Casassus P, Jarrousse B. Microscopic polyangiitis: clinical and laboratory findings in eighty-five patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:421-430. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chung SA, Seo P. Microscopic polyangiitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36:545-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ito Y, Tanaka A, Sugiura Y, Sezaki R. An autopsy case of intraabdominal hemorrhage in microscopic polyangiitis. Intern Med. 2011;50:1501-1502. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kobayashi H, Yokoe I, Murata S, Kobayashi Y. A case of microscopic polyangiitis with giant coronary aneurysm. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:583-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tamei N, Sugiura H, Takei T, Itabashi M, Uchida K, Nitta K. Ruptured arterial aneurysm of the kidney in a patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Intern Med. 2008;47:521-526. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Juvonen T, Niemelä O, Reinilä A, Nissinen J, Kairaluoma MI. Spontaneous intraabdominal haemorrhage caused by segmental mediolytic arteritis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus--an underestimated entity of autoimmune origin? Eur J Vasc Surg. 1994;8:96-100. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Soga Y, Nose M, Arita N, Komori H, Miyazaki T, Maeda T, Furuya K. Aneurysms of the renal arteries associated with segmental arterial mediolysis in a case of polyarteritis nodosa. Pathol Int. 2009;59:197-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fankhauser GT, Stone WM, Naidu SG, Oderich GS, Ricotta JJ, Bjarnason H, Money SR. The minimally invasive management of visceral artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:966-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |