Published online Sep 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i34.11966

Revised: January 7, 2014

Accepted: July 22, 2014

Published online: September 14, 2014

Processing time: 327 Days and 12.6 Hours

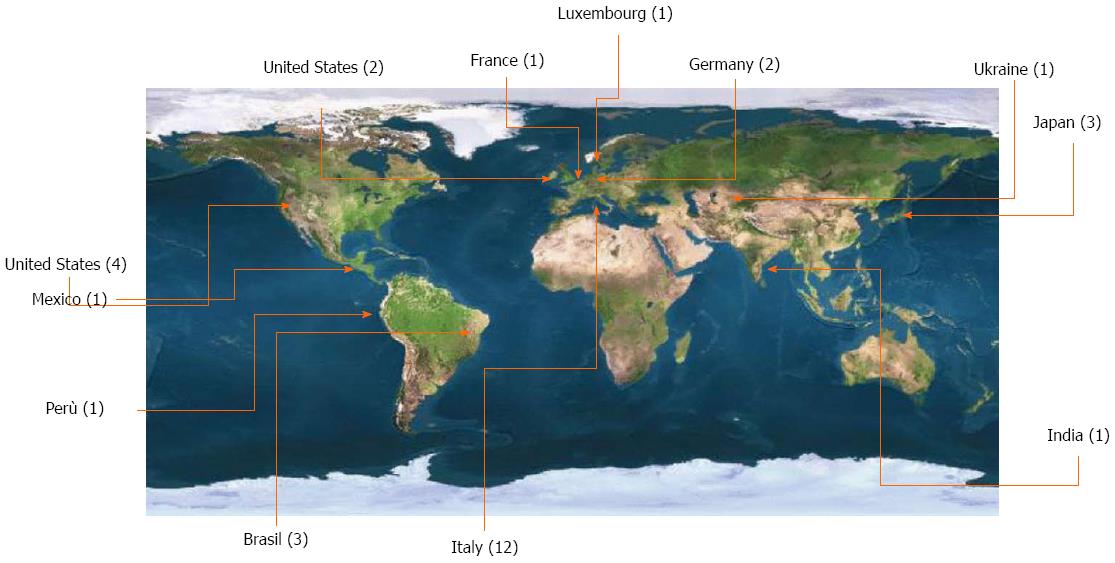

Oncological follow-up after radical gastrectomy for cancer still represents a discrepancy in the field, with many retrospective series demonstrating that early diagnosis of recurrence does not result in an improvement in patient survival; yet, many centers with high quality of care still provide routine patient follow-up after surgery by clinical and instrumental controls. This was the topic for a web round table entitled “Rationale and limits of oncological follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer” that was launched one year before the 10th International Gastric Cancer Congress. Authors having specific expertise were invited to comment on their previous publications to provide the subject for an open debate. During a three-month-long discussion, 32 authors from 12 countries participated, and 2299 people visited the dedicated web page. Substantial differences emerged between the participants: authors from Japan, South Korea, Italy, Brazil, Germany and France currently engage in instrumental follow-up, whereas authors from Eastern Europe, Peru and India do not, and British and American surgeons practice it in a rather limited manner or in the context of experimental studies. Although endoscopy is still considered useful by most authors, all the authors recognized that computed tomography scanning is the method of choice to detect recurrence; however, many limit follow-up to clinical and biochemical examinations, and acknowledge the lack of improved survival with early detection.

Core tip: A web round table entitled “Rationale and limits of oncological follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer” was launched in 2012 in preparation for the 10th International Gastric Cancer Congress. A total of 32 authors from 12 countries participated in a three-month-long discussion, and 2299 people visited the dedicated web page. The discussion revealed that the practice of follow-up after radical gastrectomy for cancer is not homogenously applied worldwide. The differences are related to culture, health system organization, and level of care.

- Citation: Baiocchi GL, Kodera Y, Marrelli D, Pacelli F, Morgagni P, Roviello F, Manzoni GD. Follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer: Results of an international web round table. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(34): 11966-11971

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i34/11966.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i34.11966

Gastric cancer is one of the most common cancers in the world. Although there has been significant progress in alternative therapies, such as chemo- and radiotherapies for other tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, surgery remains the mainstay of therapy. Even after radical gastrectomy, a significant proportion of patients experience recurrence[1-5]. Without efficacious therapies, these recurrences are almost always fatal. Many studies examining the clinical significance of follow-up after curative surgery agree that there are no survival benefits for early detection of recurrence in asymptomatic patients[6-12].

The Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (IRGGC) was formed with a special interest in the diagnosis and therapy of gastric cancer, comprised of a number of Italian centers with a common clinical policy, such as the removal of perigastric and extra-perigastric lymph nodes during surgery[13]. With consideration of the patient as a global entity, the spirit of the IRGGC is exemplified by the participation of endoscopists, pathologists, oncologists and surgeons. Indeed, the approach adopted by the group is to provide an intensive, clinical and instrumental follow-up, aimed both at minimizing the nutritional and functional sequelae of gastrectomy, and verifying if the actual “modus operandi” achieves results comparable to those of Eastern centers in terms of post-operative mortality, recurrence and survival. However, in the light of the literature, this practice should be critically analyzed.

The purpose of this highlight is to present the history and results of a web round table focused on post-operative follow-up in order to clarify issues concerning what control tools are more likely to be useful, and which have proved unnecessary - and possibly invasive - in most cases, within what time we can expect a cancer recurrence, and what proportion of patients can actually benefit from a therapy after relapse. The results of this round table discussion have stimulated an international debate about timing, methods and results of follow-up schemes currently in use.

The main theme of the 10th International Congress of the International Gastric Cancer Association held in Verona, Italy on June 19-22, 2013 was “tailored and multidisciplinary gastric cancer treatment”. This theme clearly underlined the aim of not only involving surgeons, pathologists and gastroenterologists, but also oncologists, epidemiologists, statisticians, nutritional teams, molecular biologists and radiotherapists. In preparation for the Congress, the Scientific Committee activated several web-based round tables focused on the most critical points of gastric cancer care. One such web round table was entitled “Rationale and limits of oncological follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer”. Web round tables began in 2012 and were coordinated by one or more chairmen using the Congress website.

A number of general rules were adopted to conduct the round table discussion (Table 1). For each topic, the authors of important studies were asked to preliminarily present what their own published works contributed to new experience and knowledge. These answers were then presented as short articles on the conference web site, representing a first bibliographic reference. All users were able to read these articles at any time. Round tables were open for approximately one month at different times to allow a concentrated and qualified discussion. Each round table started with a set of questions proposed by the chairmen. For each question, every participant was required to post his comment after a free web registration. At the end of the discussion, chairmen outlined conclusions that were thereafter published on the website and presented during the Congress. A separate certificate for web round table attendance was available at the Congress.

| Round table rules | |

| 1 | The Web Round Table constitutes an open scientific debate for the participants of the 10th International Gastric Cancer Congress. The Web Round Tables have a specific interest in gastric cancer |

| 2 | Registration for the forum has the value of pre-registration to the Conference |

| 3 | All content for debate is moderated by a chairman. This is not a chat |

| 4 | Topics not related to the round table will not be published |

| 5 | Specific request for personal clinical issues will not be published |

| 6 | The roundtables are addressed to the scientific community and not to patients, who have to ask their family doctors |

| 7 | Improper or offensive statements will not be published |

| 8 | Debates involving only a few people will not be continued |

| 9 | Nobody will be forced to answer personal questions |

| 10 | Chairmen will be supported by co-chairmen for a better moderation |

The chairmen of the web round table focused on follow-up were Dr. Gian Luca Baiocchi (Brescia University, Italy), Professor Yasuhiro Kodera (Nagoya University, Japan), Professor Daniele Marrelli (Siena University, Italy) and Professor Fabio Pacelli (Roma Catholic University, Italy). Five questions were initially proposed followed by an “open discussion” tool that was made available for the participants. Thirty-two authors from a total of 12 countries participated (Figure 1). Overall, 107 comments were posted: 6, 12, 14, 5 and 7 comments for questions 1-5, respectively, and 63 for the “open discussion.” Owing to the good participation and to the continuing debate, the web round table was maintained for approximately three months. At the closure date (July 1, 2012), a total of 2299 visits to the web round table contents were registered; this number increased to 4732 by October 24, 2013.

The vast majority of participants indicated that one of the accessory reasons to follow patients undergoing gastrectomy over time is to diagnose and correct any nutritional deficiencies. The first months after the intervention necessitate a close monitoring of diet, owing to obvious changes in alimentary practices. Frequent assessment of body weight and biochemical parameters such as complete blood count and iron is useful, and in some cases, nutritional supplements are given. Clearly, there is a difference between patients according to age, total vs subtotal gastrectomy, and reconstruction; total gastrectomy in elderly patients is the most risky clinical scenario for nutritional deficits. Pancreatic enzymes may theoretically represent a valuable therapeutic tool, especially in later times, when patients do not increase in body weight despite adequate food intake. Furthermore, nutritionists and other co-medicals, rather than surgeons, could be more effective in assisting patients learning a new way of feeding. Although stomal therapists have many roles at the outpatient clinic after colorectal operations, there are unfortunately no health professionals to aid upper-gastrointestinal surgeons. Indeed, it is unlikely that simple regular checks on the outpatient basis could significantly improve the nutritional status after gastrectomy; active interventions (i.e., enteral or parenteral feeding) could do, but such interventions are not easily done in routine clinical practice.

From a theoretical standpoint, the follow-up is likely to benefit a patient who receives a prognosis of death before clinical symptoms appear. Many of the round table participants state that additionally, from a psychological standpoint, the follow-up is likely to be more helpful than harmful. For example, regular checks can provide good support for the patient and a way to show them that they are not fighting the disease alone. On the other hand, participants specified that they usually do explain to the patient about recurrence, but they never discuss that he/she is going to die in a few months. Unfortunately, only clinicians from Italy, Brazil, Ukraine and Peru responded to this question, whereas there were no comments from British or American surgeons.

At the best of actual knowledge, clear evidence on oncological follow-up after gastrectomy is lacking. Rather, discrepancies are evident: while many retrospective series have definitively pointed out that diagnosis of asymptomatic recurrence does not improve survival, the daily practice in many centers is to provide the patient with ongoing clinical and instrumental checks. This outlook has almost three reasons. The first relies on the belief that biomedical research will develop in the future more effective chemotherapy schemas (as it has been done in colorectal cancer). Therefore, relaxing requirement for follow-up may prevent identification of patients who may benefit from such. Second, daily evaluation of the results of surgical and oncological therapies is crucial to improve their quality. Reliable data on recurrence and survival obtained from rigorous follow-up allow for comparisons between different therapies. Third, rather than source of stress, scheduled follow-up provides in many cases patients with a sense of protection and reassurance. Interestingly, the above mentioned results were substantially different around the world. Japanese, Korean, Italian, Brazilian, French and Dutch experts believe in the sense of routine oncological follow-up, while Authors from Eastern Europe and developing countries such as Peru and India do not. An intermediate position is registered from United States and GB, whose physicians are currently engaged in a very limited, clinical-based follow-up (apart from the context of clinical trials).

The different attitude of the participants toward follow-up practice was also reflected by very different practical approaches. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography is universally recognized as the mainstay for recurrence diagnosis, however, many experts actually perform only clinical and biochemical follow-up. In developing countries, CT scan is replaced by abdominal ultrasound. Endoscopy is still considered useful by most Authors, but it is often specified that upper gastrointestinal endoscopy detects remnant cancer more than recurrences. A further discussion of this point has been suggested by all participants.

Two different patterns of relapse were identified: in Eastern countries, the main recurrence site is the peritoneum, and no more than 50% of recurrences are detected in the first postoperative year (no more that 75% in the second year). Some Eastern authors pointed out that adjuvant chemotherapy would further prolong these times. In Western countries, on the contrary, 30% of recurrences involve the peritoneum, 30% nodal/local, 30% hematogenous and 10% multiple sites. Almost 80% of recurrences are found before 12 mo, and up to 90% are found before 24 mo.

If there is one issue concerning the treatment of gastric cancer in which the literature is quite unanimous, it is the futility of follow-up, as clearly expressed in a number of retrospective series both from Eastern[7-9] and Western centers[6,10,14] and in a systematic review[11]. In particular, it should be noted that a diagnosis of recurrence in the asymptomatic phase is unable to improve survival. Moreover, the patient’s quality of life can be worsened by anticipating the diagnosis of death. Some authors discovered that symptomatic cases are inherently aggressive and are characterized by a lower overall survival[6,10,14], and though the identification of such patients in the asymptomatic phase cannot lead to a better prognosis, it may be relevant to the therapeutic decision[15]. While acknowledging that a diagnosis of recurrence in the asymptomatic phase prolongs survival after diagnosis of recurrence, some authors clarified that the delayed diagnosis in the group with symptomatic relapse makes no difference in overall survival[8,9]. On the other hand, the cost of follow-up programs is clear. An assessment made by the Tokyo Cancer Center estimates that a surgical department with a medium volume of gastric cancer surgery - about 50 radical resections for gastric cancer a year - must bear the weight of 150 patients in follow-up every year in the fifth year, and 200 in the tenth year. These figures are even higher in Eastern centers with a high volume and high percentage of early gastric cancers[11].

Many experts participating in the web Consensus Conference actually believe that a follow-up time ranging from 36 and 60 mo is at the same time necessary and useful: oncological follow-up more than 5 years after surgery likely is not cost-effective. Obviously, a longer the follow-up would allow to diagnose a number of early cancer at other sites, but this should be more properly named screening than follow-up.

There was also no consensus concerning the methods used during the follow-up, ranging from a follow-up based only on clinical examination to one based on sequential computed tomography and positron emission tomography. Finally, upper-gastrointestinal endoscopy is still performed all over the world, even though the majority of experts recognize that intraluminal recurrences are very infrequent, and searching for a second tumor is screening rather than follow-up.

This international, web-based round table was performed to explore the expert’s opinion on the sense of routine follow-up after gastrectomy, searching in particular for eventual advantages in terms of early recurrence detection, availability of treatments and improved survival; diagnosis and eventual treatment of nutritional deficiencies are a second important issue. The round table was surprisingly well participated by authors who approached the issues with passion and diligence, including those from industrialized countries as well as countries with lower technological content and with less developed health systems. Moreover, this is a subject that is suitable for different interpretations, even philosophical in nature as well as technical.

Finally, many participants recognized that gastric cancer follow-up does not improve survival, as the majority of recurrent cases are not amenable to curative care. As a consequence, a more intensive follow-up is unlikely to have a clinical relevance, owing to the very small proportion of cases which potentially could undergo a kind of treatment. However, this very small proportion is no longer nil, and this is why many surgeons worldwide continue to give their patients the chance of scheduled examinations. An interesting and unexpected debate was also stimulated by the provocative observation made by a Japanese surgeon that “for the United States and British patients, the surgeon is essentially an engineer who opens a lid of the patient’s abdomen and removes what should not be there”. In Japan, the surgeon is a “savior” and patients tend to become insane when a surgeon declares that the patient does not need to come to see him or her anymore.

The real goal of this discussion would be reached by individualization of follow-up on the basis of the recurrence risk [a proposal of follow-up tailored to a prognostic score[16] has been made by the IRGGC (Table 2)]. On one hand, high-risk patients unfortunately relapse in few months: they may be strictly screened for recurrence, but no significant survival benefit should be expected. On the other hand, low-risk patients should undergo a mild but prolonged follow-up (late recurrences are more frequently locoregional), taking into account the possibility of second cancers. Finally, intermediate-risk cases should be managed after further selection, eventually based upon newly discovered (biological?) features[17].

| Level | Time (mo) | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 27 | 30 | 33 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 54 | 60 | |

| Mild | ||||||||||||||||

| Tumor markers | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Abdominal ultrasound | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Chest X-ray | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| Thoraco-abdominal CT | ||||||||||||||||

| Endoscopy | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Moderate | ||||||||||||||||

| Tumor markers | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Abdominal ultrasound | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Chest X-ray | ||||||||||||||||

| Thoraco-abdominal CT | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Endoscopy | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Intensive | ||||||||||||||||

| Tumor markers | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Abdominal ultrasound | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Chest X-ray | ||||||||||||||||

| Thoraco-abdominal CT | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Endoscopy | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

We would like to thank the following collaborators who contributed to the round table: Ferdinando Agresta, Luca Ansaloni, Luca Arru, Josè Carvalho, Bruno Compagnoni, Alberto Di Leo, Federico Gheza, Paulo Kassab, Richard Hardwick, Daisuke Ichikawa, Carlos Malheiros, Paul Mansfield, Sarah Molfino, Katja Ott, Atsushi Nashimoto, Shaun Preston, Stefano Rausei, Christoph Shuhmacher, Vivian Strong, Daniela Zanotti, Martin Karpeh, Guido Tiberio, and Daniel Coit.

P- Reviewer: Bonavina L, Kim HH, Xu HM S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Roviello F, Marrelli D, de Manzoni G, Morgagni P, Di Leo A, Saragoni L, De Stefano A. Prospective study of peritoneal recurrence after curative surgery for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1113-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shiraishi N, Inomata M, Osawa N, Yasuda K, Adachi Y, Kitano S. Early and late recurrence after gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Univariate and multivariate analyses. Cancer. 2000;89:255-261. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Schwarz RE, Zagala-Nevarez K. Recurrence patterns after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: prognostic factors and implications for postoperative adjuvant therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:394-400. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Baiocchi GL, Tiberio GA, Minicozzi AM, Morgagni P, Marrelli D, Bruno L, Rosa F, Marchet A, Coniglio A, Saragoni L. A multicentric Western analysis of prognostic factors in advanced, node-negative gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2010;252:70-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Marrelli D, Roviello F, de Manzoni G, Morgagni P, Di Leo A, Saragoni L, De Stefano A, Folli S, Cordiano C, Pinto E. Different patterns of recurrence in gastric cancer depending on Lauren’s histological type: longitudinal study. World J Surg. 2002;26:1160-1165. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Böhner H, Zimmer T, Hopfenmüller W, Berger G, Buhr HJ. Detection and prognosis of recurrent gastric cancer--is routine follow-up after gastrectomy worthwhile? Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:1489-1494. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Eom BW, Ryu KW, Lee JH, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Park SR, Lee JS. Oncologic effectiveness of regular follow-up to detect recurrence after curative resection of gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:358-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kodera Y, Ito S, Yamamura Y, Mochizuki Y, Fujiwara M, Hibi K, Ito K, Akiyama S, Nakao A. Follow-up surveillance for recurrence after curative gastric cancer surgery lacks survival benefit. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:898-902. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tan IT, So BY. Value of intensive follow-up of patients after curative surgery for gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:503-506. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Villarreal-Garza C, Rojas-Flores M, Castro-Sánchez A, Villa AR, García-Aceituno L, León-Rodríguez E. Improved outcome in asymptomatic recurrence following curative surgery for gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2011;28:973-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Whiting J, Sano T, Saka M, Fukagawa T, Katai H, Sasako M. Follow-up of gastric cancer: a review. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:74-81. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Verlato G, Roviello F, Marchet A, Giacopuzzi S, Marrelli D, Nitti D, de Manzoni G. Indexes of surgical quality in gastric cancer surgery: experience of an Italian network. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:594-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bennett JJ, Gonen M, D’Angelica M, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Is detection of asymptomatic recurrence after curative resection associated with improved survival in patients with gastric cancer? J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:503-510. [PubMed] |

| 14. | D'Ugo D, Biondi A, Tufo A, Persiani R. Follow-up: the evidence. Dig Surg. 2013;30:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Park SH, Mok YJ. Benefit of post-operative surveillance for recurrence after curative resection for gastric cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:969-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marrelli D, Caruso S, Roviello F. Follow-up and treatment of recurrence. Surgery in the Multimodal Management of Gastric Cancer. Verlag, Italia: Springer 2012; . |

| 17. | Baiocchi GL, Marrelli D, Verlato G, Morgagni P, Giacopuzzi S, Coniglio A, Marchet A, Rosa F, Capponi MG, Di Leo A. Follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer: an appraisal of the italian research group for gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:2005-2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |