Published online Aug 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10478

Revised: June 11, 2014

Accepted: July 11, 2014

Published online: August 14, 2014

Processing time: 145 Days and 0.8 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the safety and feasibility of a modified delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy (DSG) in totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG).

METHODS: We performed a case-control study enrolling 63 patients with distal gastric cancer (GC) undergoing TLDG with a DSG from January 2013 to June 2013. Twenty-two patients underwent a conventional DSG (Con-Group), whereas the other 41 patients underwent a modified version of the DSG (Mod-Group). The modified procedure required only the instruments of the surgeon and assistant to complete the involution of the common stab incision and to completely resect the duodenal cutting edge, resulting in an anastomosis with an inverted T-shaped appearance. The clinicopathological characteristics, surgical outcomes, anastomosis time and complications of the two groups were retrospectively analyzed using a prospectively maintained comprehensive database.

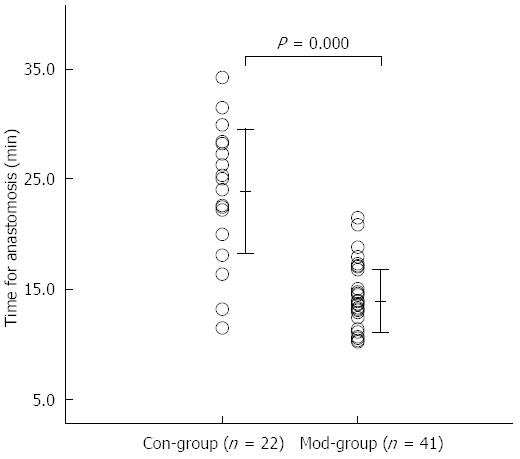

RESULTS: DSG procedures were successfully completed in all of the patients with histologically complete (R0) resections, and none of these patients required conversion to open surgery. The clinicopathological characteristics of the two groups were similar. There were no significant differences between the groups in the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, extension of the lymph node (LN) dissection and number of dissected LNs (150.8 ± 21.6 min vs 143.4 ± 23.4 min, P = 0.225 for the operative time; 26.8 ± 11.3 min vs 30.6 ± 14.8 mL, P = 0.157 for the intraoperative blood loss; 4/18 vs 3/38, P = 0.375 for the extension of the LN dissection; and 43.9 ± 13.4 vs 39.5 ± 11.5 per case, P = 0.151 for the number of dissected LNs). The anastomosis time, however, was significantly shorter in the Mod-Group than in the Con-Group (13.9 ± 2.8 min vs 23.9 ± 5.6 min, P = 0.000). The postoperative outcomes, including the times to out-of-bed activities, first flatus, resumption of soft diet and postoperative hospital stay, as well as the anastomosis size, did not differ significantly (1.9 ± 0.6 d vs 2.3 ± 1.5 d, P = 0.228 for the time to out-of-bed activities; 3.2 ± 0.9 d vs 3.5 ± 1.3 d, P = 0.295 for the first flatus time; 7.5 ± 0.8 d vs 8.1 ± 4.3 d, P = 0.489 for the resumption of a soft diet time; 14.3 ± 10.6 d vs 11.5 ± 4.9 d, P = 0.148 for the postoperative hospital stay; and 30.5 ± 3.6 mm vs 30.1 ± 4.0 mm, P = 0.730 for the anastomosis size). One patient with minor anastomotic leakage in the Con-Group was managed conservatively; no other patients experienced any complications around the anastomosis. The operative complication rates were similar in the Con- and Mod-Groups (9.1% vs 7.3%, P = 1.000).

CONCLUSION: The modified DSG, an alternative reconstruction in TLDG for GC, is technically safe and feasible, with a simpler process that reduces the anastomosis time.

Core tip: A modified delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy (DSG) technique was introduced to reduce surgical trauma in patients undergoing totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG) for gastric cancer (GC). The clinicopathological characteristics, surgical outcomes, anastomosis times and complications of the patients undergoing conventional and modified DSG (Con-Group, n = 22 vs Mod-Group, n = 41) were retrospectively compared using a prospectively maintained comprehensive database to evaluate the safety and feasibility of the procedure. The results of the study confirmed that the modified DSG was technically safe and feasible, with a simpler process that reduced the anastomosis time. The modified DSG may be an alternative reconstruction in TLDG for GC.

- Citation: Huang CM, Lin M, Lin JX, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lu J. Comparision of modified and conventional delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy in totally laparoscopic surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(30): 10478-10485

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i30/10478.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10478

During the past 20 years, laparoscopic surgery has become more widely accepted as a surgical treatment for gastric cancer (GC) because of its minimally invasive approach and its similar short-term results and long-term survival outcomes in comparison to open gastrectomy[1-4]. Although reconstruction of the digestive tract is important during laparoscopic surgery for GC, it is technically difficult, with the Billroth-I (B-I) anastomosis after totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG) considered to be especially complex. A method for intracorporeal B-I anastomosis, called delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy (DSG) and using only endoscopic linear staplers, was first reported in 2002[5]. This method has been accepted and performed in some Asian countries, such as Japan and South Korea[6-8], due to its simplicity and satisfactory results[9], and it has been performed at our institution since November 2012. During the implementation process, we simplified the operation procedure and proposed a modified DSG. Here, we introduce this modified DSG and evaluate its safety, feasibility and clinical results in patients undergoing TLDG for GC.

Between January 2013 and June 2013, 63 patients with primary distal GC underwent a DSG (B-I anastomosis) combined with a TLDG with a D1+/D2 lymphadenectomy in the Department of Gastric Surgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital. Twenty-two patients underwent conventional DSG (Con-Group), whereas the other 41 patients underwent a modified version of the DSG (Mod-Group). Distal GC was preoperatively confirmed by the analysis of endoscopic biopsy specimens. The pretreatment tumor site, depth of invasion, extent of lymph node (LN) metastasis and metastatic disease were evaluated by endoscopy, computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography of the abdomen and/or chest radiography. Patients with distant metastasis were excluded. A retrospective analysis was performed, using a prospectively maintained comprehensive database, to evaluate the safety and feasibility of the technique. The surgical procedure, including its advantages and risks, was explained to all patients before the surgery. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Fujian Medical Union hospital. Written consent was obtained from the patients for their information to be stored in the hospital database and used for research.

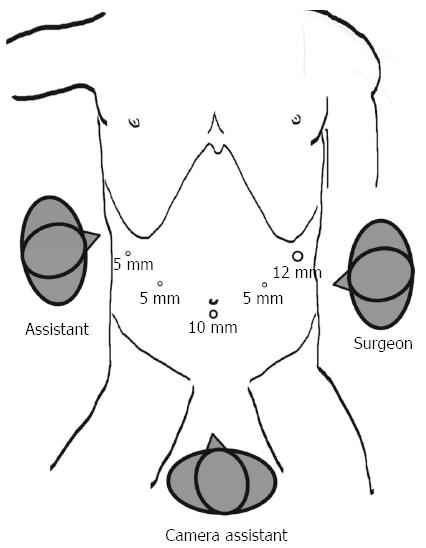

All of the patients voluntarily elected laparoscopic surgery and provided written informed consent prior to the surgery. The LN dissections were based on the guidelines of the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma (JCGC)[10]. The gastroduodenostomies were reconstructed using an endoscopic linear stapler (Tri-Staple™ Technology, Covidien, United States). Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position with the legs apart and the head elevated approximately 10 to 20 degrees. A 10-mm trocar for the laparoscope was inserted 1 cm below the umbilicus; a 12-mm trocar was introduced into the left preaxillary line 2 cm below the costal margin as a major hand port; a 5-mm trocar was inserted into the left midclavicular line 2 cm above the umbilicus as an accessory port; a second 5-mm trocar was placed at the contralateral site; and a third 5-mm trocar was inserted into the right preaxillary line 2 cm below the costal margin for exposure. The surgeon stood on the patient’s left side, and the assistant stood on the patient’s right side. The camera assistant was placed between the patient’s legs (Figure 1). The mobilization of the stomach and LN dissection were performed as described[11,12].

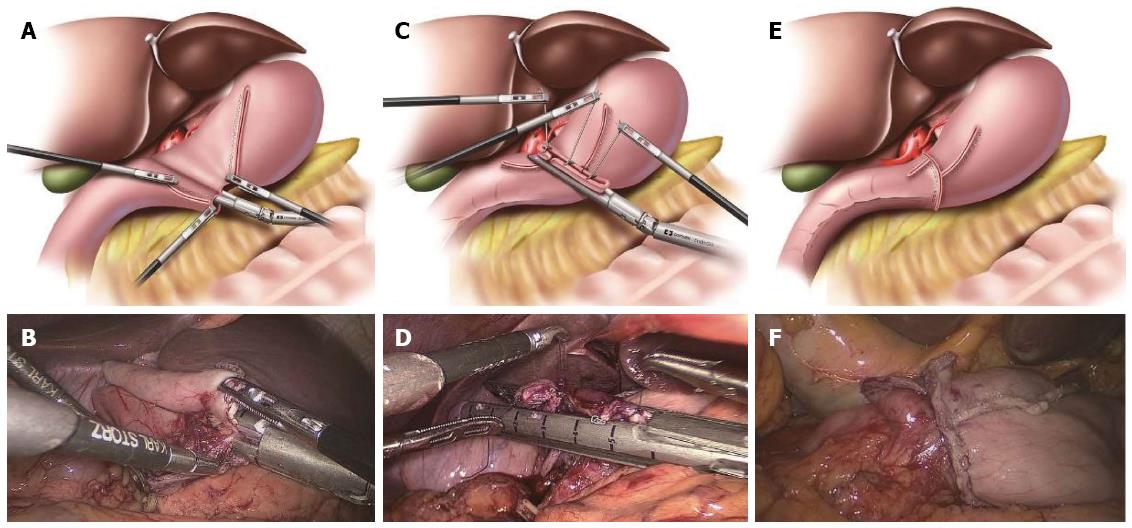

Conventional DSG has been described in detail previously[5]. In our institution, we used the 60-mm endoscopic linear stapler rather than the 45-mm endoscopic linear stapler, which differed from Kanaya et al[5]. After the stomach and duodenum were transected in the predetermined positions using three endoscopic linear staplers, the specimen was placed into a plastic specimen bag intracorporeally. Small incisions were made on the greater curvature of the remnant stomach and the posterior side of the duodenum. A 60-mm endoscopic linear stapler was inserted through the major hand port, with one limb in each incision. Following the approximation of the posterior walls of the gastric remnant and duodenum, the forks of the stapler were closed and fired, creating a V-shaped anastomosis on the posterior wall. Three sutures were added to each end of the common stab incision and to the cutting edges of the stomach and duodenum to obtain a better involution and pull. Finally, the common stab incision was closed with the stapler, resulting in the reconstruction of the intracorporeal digestive tract (Figure 2). A total of five staplers were used.

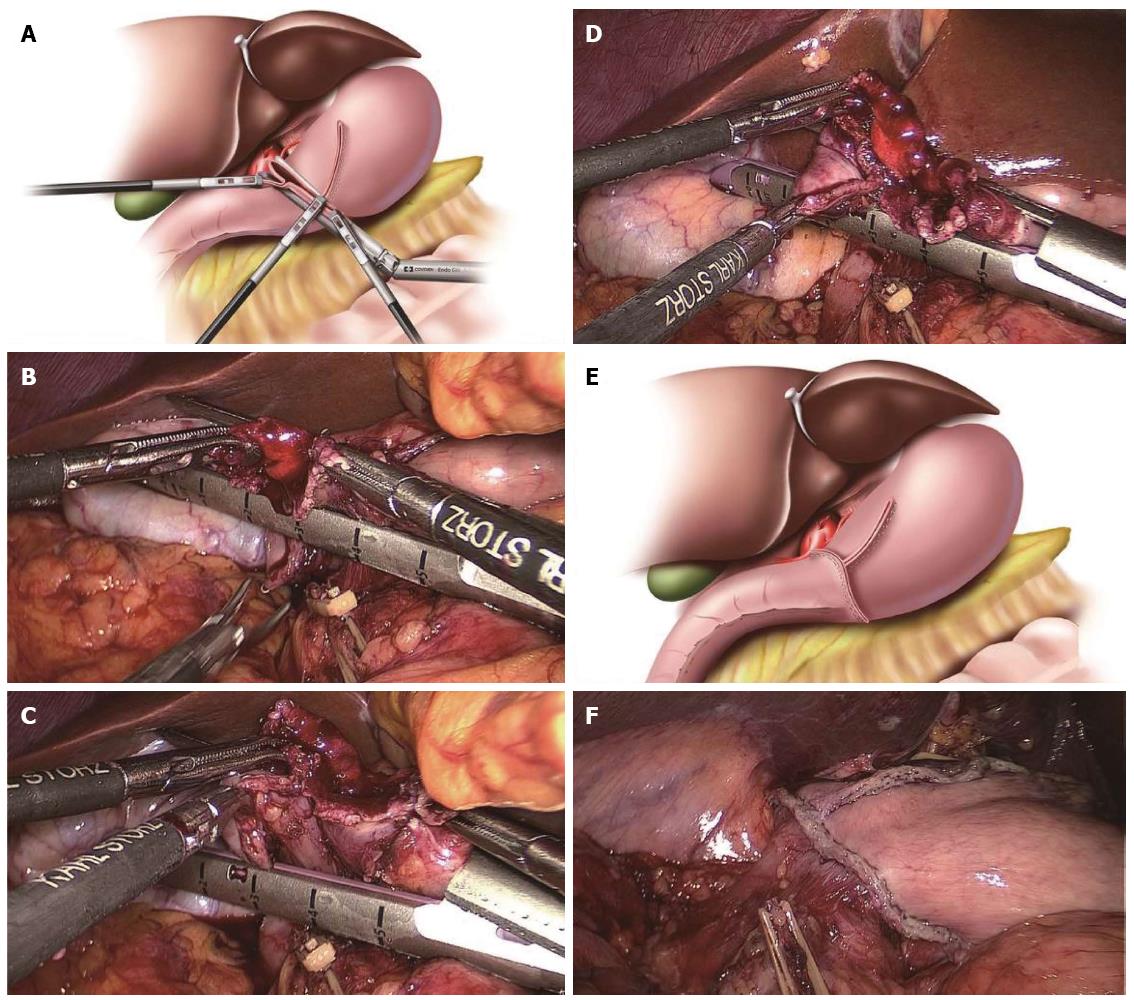

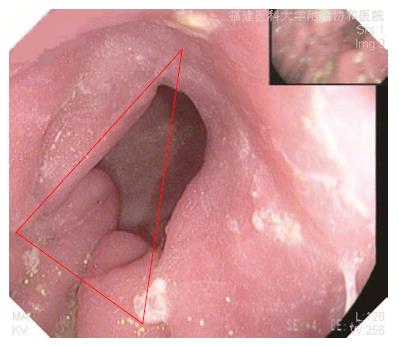

All procedures prior to the V-shaped anastomosis were the same as described above. After checking the V-shaped anastomosis via the common stab incision, the lower end of the common stab incision was pulled by the surgeon’s left forceps, and the other end was pulled by the assistant’s left forceps. At the same time, the surgeon, using his right hand, inserted the endoscopic linear stapler to close around the common stab incision and provide an involution. The other end of the duodenal cutting edge was pulled up into the stapler by the assistant’s right forceps. Therefore, the intersection of the duodenal cutting edge and the common closed edge was resected at the same time to lessen the anastomotic weak point when the common stab incision was closed with the stapler. The cutting line of closing the common stab incision should be maintained perpendicular to the cutting edge of the remnant stomach, and as little tissue should be removed as possible on the premise of completely resecting the duodenal cutting edge. The anastomosis appeared as an inverted T-shape (Figure 3). A total of five staplers were used.

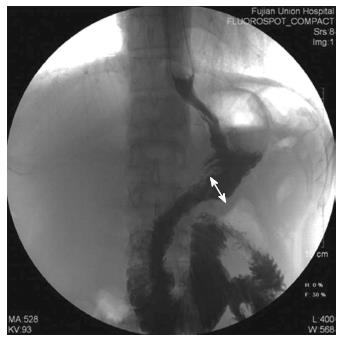

The patients’ clinicopathological characteristics [including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), tumor site, tumor size, proximal and distal margins and pathological tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage], intraoperative outcomes (including operative time, anastomosis time, intraoperative blood loss, extent of the LN dissection and the number of dissected LNs), postoperative outcomes (including the times to out-of-bed activities, first flatus, earlier resumption of liquid and soft diet, postoperative hospital stay and the anastomosis size) and postoperative complications were compared in the two groups. The clinical and pathological staging were performed in accordance with the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) seventh edition of Gastric Cancer TNM Staging[13]. The anastomosis time was defined as the time from transecting the duodenum to closing the common stab incision. The anastomosis was checked for leakage on postoperative days 7-9 by performing upper gastrointestinal radiography using diatrizoate meglumine as the contrast medium. The anastomosis size was defined as the inner diameter of the anastomosis, measured on upper gastrointestinal radiography films in which the anastomotic site was fully filled with contrast medium (Figure 4). The anastomoses were evaluated at 3 mo by gastroscopy (Figure 5).

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, United States). The data are expressed as mean ± SD. The categorical variables were analyzed by the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, while the continuous variables were analyzed by Student’s t test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The 63 patients included 42 males (66.7%) and 21 females (33.3%) with a mean age of 57.7 ± 11.7 years (range 33 to 81 years) and a mean BMI of 21.96 ± 2.95 kg/m2 (range 16.2 to 29.3 kg/m2). All patients underwent histologically complete (R0) resections. The mean tumor size was 32.7 ± 18.7 mm (range 8.0 to 85.0 mm). The pathological TNM stages included IA (n = 22), IB (n = 14), IIA (n = 11), IIB (n = 8), IIIA (n = 5), and IIIB (n = 3). There were no significant differences between the groups in the age, gender, BMI, tumor site, tumor size, proximal and distal margins or AJCC pathological TNM stage (Table 1).

| Item | Con-group (n = 22) | Mod-group (n = 41) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 54.4 ± 11.2 | 59.5 ± 11.7 | 0.096 |

| Gender (n, M/F) | 12/10 | 30/11 | 0.135 |

| BMI (kg/m2, ≥ 23/< 23) | 11/11 | 30/11 | 0.066 |

| Tumor site (n, LCGA/GCGA) | 19/3 | 40/1 | 0.232 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 27.6 ± 17.1 | 35.4 ± 19.2 | 0.116 |

| Proximal margin (mm) | 55.3 ± 15.0 | 53.1 ± 16.1 | 0.606 |

| Distal margin (mm) | 40.4 ± 15.6 | 39.8 ± 13.5 | 0.883 |

| AJCC pT stage (n) | 0.1841 | ||

| T1 | 12 | 14 | |

| T2 | 5 | 17 | |

| T3 | 3 | 9 | |

| T4a | 2 | 1 | |

| AJCC pN stage (n) | 0.5641 | ||

| N0 | 13 | 22 | |

| N1 | 6 | 12 | |

| N2 | 2 | 7 | |

| N3 | 1 | 0 | |

| AJCC pTNM stage (n) | 0.640 | ||

| I | 14 | 22 | |

| II | 5 | 14 | |

| III | 3 | 5 |

DSG was successfully completed in all of the patients, in combination with TLDG with D1+/D2 lymphadenectomy, with none of these patients requiring conversion to open surgery. The details of the intraoperative outcomes are shown in Table 2. The Con- and Mod-Groups had similar operative time, intraoperative blood loss, extent of the LN dissection and number of dissected LNs.

| Item | Con-group (n = 22) | Mod-group (n = 41) | P value |

| Intraoperative outcomes | |||

| Conversion to open surgery (n) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Operative time (min) | 150.8 ± 21.6 | 143.4 ± 23.4 | 0.225 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 26.8 ± 11.3 | 30.6 ± 14.8 | 0.157 |

| Extent of LN dissection (n) | 0.375 | ||

| D1+/D2 | 4/18 | 3/38 | |

| Number of dissected LNs (per case) | 43.9 ± 13.4 | 39.5 ± 11.5 | 0.151 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Time to out-of-bed activities (d) | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 0.228 |

| First flatus time (d) | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.295 |

| Time to resume liquid diet (d) | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 0.137 |

| Time to resume soft diet (d) | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 8.1 ± 4.3 | 0.489 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 14.3 ± 10.6 | 11.5 ± 4.9 | 0.148 |

| Anastomosis size (mm) | 30.5 ± 3.6 | 30.1 ± 4.0 | 0.730 |

The mean anastomosis time for all of the patients was 17.4 ± 6.2 min (range 10.2 to 34.2 min). The anastomosis time was significantly less in the Mod-Group than in the Con-Group (13.9 ± 2.8 min vs 23.9 ± 5.6 min, P = 0.000; Figure 6).

The overall postoperative outcomes are presented in Table 2. The postoperative outcomes, including the times to out-of-bed activities, first flatus, resumption of a soft diet and postoperative hospital stay, as well as the anastomosis size, did not differ significantly (P > 0.05).

One patient in the Con-Group experienced a minor anastomotic leakage after surgery (4.5%, 1/22); this leakage occurred on the anterior wall of the anastomosis at the site of the common closed edge and was cured after conservative treatment for 57 d. None of the other patients in either group experienced any anastomosis-related complications, such as anastomotic leakage, anastomotic stricture and anastomotic hemorrhage. The overall postoperative complications are shown in Table 3. Two patients in the Con-Group (9.1%) experienced postoperative complications, one with lymphorrhagia and celiac infection, and the other, the patient with the minor anastomotic leakage, also experienced a respiratory infection at the same time. Three patients in the Mod-Group (7.3%) experienced postoperative complications, one with a urinary tract infection, one with an inflammatory intestinal obstruction and respiratory infection, and one with gastric atony. The postoperative morbidity rates were similar in the two groups. All of these postoperative complications were successfully treated by conservative methods. There were no deaths in either group.

| Item | Con-Group (n = 22) | Mod-Group (n = 41) | P value |

| Anastomosis-related complications | |||

| Anastomotic leakage | 1 | 0 | 0.3491 |

| Anastomotic stricture | 0 | 0 | - |

| Anastomotic hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | - |

| Other complications | |||

| Lymphorrhagia | 1 | 0 | 0.3491 |

| Postoperative celiac infection | 1 | 0 | 0.3491 |

| Respiratory infection | 1 | 1 | 1.0001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 1 | 1.0001 |

| Inflammatory intestinal obstruction | 0 | 1 | 1.0001 |

| Gastric atony | 0 | 1 | 1.0001 |

| Overall postoperative complications2 | 2 (9.1) | 3 (7.3) | 1.000 |

| Postoperative mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for GC. Operation methods are sought that reduce surgical trauma and optimize the patient’s quality of life. Since the introduction of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) for GC in 1994[14], laparoscopic surgery has become widely used in patients with GC. The B-I anastomosis is preferred for reconstruction after LADG because of its relative simplicity and physiological advantages, which include allowing food to pass through the duodenum and reducing the postoperative incidence of cholecystitis and cholelithiasis[15-17]. However, anastomosis during totally laparoscopic surgery is technically difficult. DSG, a method of B-I anastomosis after TLDG using only endoscopic linear staplers[5], has been utilized in several Asian countries, including Japan and Korea, due to its simplicity[6-8]. TLDG with DSG has been shown to be superior to open gastrectomy[18,19], especially in obese patients[8,19,20], and it is regarded as safe and feasible[6-9,18-20].

The laparoscopic suturing used in the conventional DSG procedure to obtain an involution of the common stab incision was found to require a relatively long period of time. Moreover, this method contained a duodenal blind side and two intersections of the cutting edge of the remnant stomach with the duodenum and common closed edge, which may cause poor blood supply to the duodenal stump and yield two weak points on the anastomosis that increase the risk of anastomosis-related complications. Furthermore, the postoperative morbidity rates of anastomosis-related complications after DSG ranged from 1.0% to 12.7%[6,9,19-21]. Therefore, we modified the conventional DSG procedure to reduce the anastomosis time and lessen the surgical trauma, based on our surgical experience. First, we omitted the step of the laparoscopic suturing used in conventional DSG to produce an involution of the common stab. Instead, the modified DSG required only the instruments of the surgeon and assistant to directly grasp the tissue and accomplish the involution of the common stab incision. Thus, it simplified the operation procedure and shortened the anastomosis time. Additionally, the mean anastomosis time was significantly shorter in the Mod- than in the Con-Group. Furthermore, the anastomotic line tending to run parallel to the direction of the transection of the duodenum was in less danger of the vascular deterioration of the duodenum close to the anastomosis. The complete resection of the duodenal cutting edge also avoided a poor blood supply to the duodenal stump. Meanwhile, reducing the anastomotic weak point resulted in a more sturdily constructed anastomosis, with less risk of anastomosis-related complications. No patient in the Mod-Group experienced any anastomosis-related complications.

Before the DSG, under the premise of R0 resection for the tumor, a sufficiently long duodenal stump and a suitably sized remnant stomach would be retained. Furthermore, when the common stab incision was closed and the duodenal cutting edge was completely resected, we selected a direction that was perpendicular to the cutting edge of the remnant stomach and removed as little of the tissue as possible. Therefore, the complete resection of duodenal cutting edge would not increase the anastomotic tension. In addition, the perpendicular cutting line may also prevent a decrease in the anastomosis size and anastomotic strictures in the modified technique. Our results also showed that the mean anastomosis size in the Mod-Group was similar to that in the Con-Group.

The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients in the Con- and Mod-Groups were comparable, with no significant between-group differences in the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, number of dissected LNs or postoperative outcomes. All patients successfully completed the TLDG with the DSG without conversion to laparotomy. These results indicated that the modified DSG procedure was as safe and feasible as the conventional DSG, with similar clinical results.

During the modified procedure, the endoscopic linear stapler should first be closed around the common stab incision when obtaining an involution, after which the assistant should pull up the other end of the duodenal cutting edge into the stapler, with the two hands coordinating with each other. The common stab incision should be closed vertically to the gastric cutting edge using the stapler, yielding the widest possible anastomosis and avoiding anastomotic strictures. After the anastomotic tension and quality are checked, a secure suture should be added to reinforce the anastomosis if anastomotic oozing occurs, especially at the intersection of the gastric cutting edge and the common closed edge. Because the DSG requires a sufficiently long duodenal stump and suitably sized remnant stomach to reduce the anastomotic tension, an anastomosis may be more suitable in early GC. Early tumors, however, are often difficult to identify during total laparoscopy. Thus, intraoperative gastroscopy could be used for accurate positioning to ensure an R0 tumor resection. Moreover, preoperative gastroscopic biopsy and intraoperative endoscopic ultrasound are recommended to determine the cutting line[22], whereas endoscopic ink marking may be advantageous at its location[23].

In conclusion, the modified DSG was technically safe and feasible in patients with GC undergoing TLDG. It may be an alternative reconstruction in TLDG for GC, with a simpler process that reduces the anastomosis time and acceptable surgical outcomes. Longer follow-ups are needed in the future to confirm these results. To be accepted as a treatment of choice in TLDG for GC, a well-designed prospective randomized controlled trial comparing short-term and long-term outcomes in a larger number of patients is necessary.

We are grateful to our patients and the staff who were involved in the patients’ care for making this study possible.

Laparoscopic surgery has become more widely accepted as a surgical treatment for gastric cancer (GC). Although reconstruction of the digestive tract is important during laparoscopic surgery for GC, it is technically difficult, with the Billroth-I (B-I) anastomosis after totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy (TLDG) considered to be especially complex. The delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy (DSG), a method of B-I anastomosis after TLDG using only endoscopic linear staplers, has been utilized in several Asian countries, including Japan and Korea, due to its simplicity and satisfactory results, and it has been performed at our institution since November 2012. During the implementation process, we simplified the operation procedure and proposed a modified DSG.

Anastomosis during totally laparoscopic surgery is technically difficult, with the B-I anastomosis after TLDG considered especially complex.

The authors modified the conventional DSG procedure to lessen the anastomosis time and reduce surgical trauma. The modified procedure required only the instruments of the surgeon and assistant to complete the involution of the common stab incision, rather than the laparoscopic suturing, and to completely resect the duodenal cutting edge. Thus, the modified procedure simplified the operation procedure, shortened the anastomosis time, avoided poor blood supply to the duodenal stump and reduced the anastomotic weak point. The mean anastomosis time was significantly shorter in the modified DSG group (Mod-Group) than in the conventional DSG group (Con-Group). No patient in the Mod-Group experienced any anastomosis-related complications.

The study results suggest that the modified DSG is technically safe and feasible in patients with GC undergoing TLDG. It may be an alternative reconstruction in TLDG for GC, with a simpler process that lessens the anastomosis time and acceptable surgical outcomes.

The present study provides an insightful and well-illustrated review of the safety and feasibility of a modified DSG in TLDG. Based on the experience with 63 gastric cancer patients undergoing TLDG with DSG, the conclusion is that modified DSG is technically safe and feasible, with acceptable surgical outcomes. This is a well-written and quite instructive work.

P- Reviewer: Slomiany BL, Wang ZW S- Editor: Ding Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 655] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N. A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Park do J, Han SU, Hyung WJ, Kim MC, Kim W, Ryu SY, Ryu SW, Song KY, Lee HJ, Cho GS. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a large-scale multicenter retrospective study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1548-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Qiu J, Pankaj P, Jiang H, Zeng Y, Wu H. Laparoscopy versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kanaya S, Gomi T, Momoi H, Tamaki N, Isobe H, Katayama T, Wada Y, Ohtoshi M. Delta-shaped anastomosis in totally laparoscopic Billroth I gastrectomy: new technique of intraabdominal gastroduodenostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:284-287. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Okabe H, Obama K, Tsunoda S, Tanaka E, Sakai Y. Advantage of completely laparoscopic gastrectomy with linear stapled reconstruction: a long-term follow-up study. Ann Surg. 2014;259:109-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim JJ, Song KY, Chin HM, Kim W, Jeon HM, Park CH, Park SM. Totally laparoscopic gastrectomy with various types of intracorporeal anastomosis using laparoscopic linear staplers: preliminary experience. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:436-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim MG, Kim KC, Kim BS, Kim TH, Kim HS, Yook JH, Kim BS. A totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy can be an effective way of performing laparoscopic gastrectomy in obese patients (body mass index≥30). World J Surg. 2011;35:1327-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kanaya S, Kawamura Y, Kawada H, Iwasaki H, Gomi T, Satoh S, Uyama I. The delta-shaped anastomosis in laparoscopic distal gastrectomy: analysis of the initial 100 consecutive procedures of intracorporeal gastroduodenostomy. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:365-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2869] [Article Influence: 204.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang JB, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Lin BJ, Lu HS. [Efficiency of laparoscopic D2 radical gastrectomy in gastric cancer: experiences of 218 patients]. Zhonghua Wai Ke Zazhi. 2010;48:502-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang CM, Wang JB, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Lu HS. [Short-term efficacy of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with lymph node dissection in distal gastric cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Zazhi. 2009;12:584-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 814] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146-148. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Huang CM, Lin JX. [Difficulty and settlement of digestive reconstruction after laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Zazhi. 2013;16:121-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim DG, Choi YY, An JY, Kwon IG, Cho I, Kim YM, Bae JM, Song MG, Noh SH. Comparing the short-term outcomes of totally intracorporeal gastroduodenostomy with extracorporeal gastroduodenostomy after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a single surgeon’s experience and a rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3153-3161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kinoshita T, Shibasaki H, Oshiro T, Ooshiro M, Okazumi S, Katoh R. Comparison of laparoscopy-assisted and total laparoscopic Billroth-I gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a report of short-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1395-1401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ikeda O, Sakaguchi Y, Aoki Y, Harimoto N, Taomoto J, Masuda T, Ohga T, Adachi E, Toh Y, Okamura T. Advantages of totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy over laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2374-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim BS, Yook JH, Choi YB, Kim KC, Kim MG, Kim TH, Kawada H, Kim BS. Comparison of early outcomes of intracorporeal and extracorporeal gastroduodenostomy after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:387-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim MG, Kawada H, Kim BS, Kim TH, Kim KC, Yook JH, Kim BS. A totally laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with gastroduodenostomy (TLDG) for improvement of the early surgical outcomes in high BMI patients. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1076-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Noshiro H, Iwasaki H, Miyasaka Y, Kobayashi K, Masatsugu T, Akashi M, Ikeda O. An additional suture secures against pitfalls in delta-shaped gastroduodenostomy after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:385-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hyung WJ, Lim JS, Cheong JH, Kim J, Choi SH, Song SY, Noh SH. Intraoperative tumor localization using laparoscopic ultrasonography in laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Osugi H. Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with regional lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:758-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |