Published online Aug 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10470

Revised: May 8, 2014

Accepted: May 25, 2014

Published online: August 14, 2014

Processing time: 184 Days and 16.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) for rectal neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) and the differential diagnosis of rectal NENs from other subepithelial lesions (SELs).

METHODS: The study group consisted of 36 consecutive patients with rectal NENs histopathologically diagnosed using biopsy and/or resected specimens. The control group consisted of 31 patients with homochronous rectal non-NEN SELs confirmed by pathology. Epithelial lesions such as cancer and adenoma were excluded from this study. One EUS expert blinded to the histological results reviewed the ultrasonic images. The size, original layer, echoic intensity and homogeneity of the lesions and the perifocal structures were investigated. The single EUS diagnosis recorded by the EUS expert was compared with the histological results.

RESULTS: All NENs were located at the rectum 2-10 cm from the anus and appeared as nodular (n = 12), round (n = 19) or egg-shaped (n = 5) lesions with a hypoechoic (n = 7) or intermediate (n = 29) echo pattern and a distinct border. Tumors ranged in size from 2.3 to 13.7 mm, with an average size of 6.8 mm. Homogeneous echogenicity was seen in all tumors except three. Apart from three patients (stage T2 in two and stage T3 in one), the tumors were located in the second and/or third wall layer without involvement of the fourth and fifth layers. In the patients with stage T1 disease, the tumors were located in the second wall layer only in seven cases, the third wall layer only in two cases, and both the second and third wall layers in 27 cases. Approximately 94.4% (34/36) of rectal NENs were diagnosed correctly by EUS, and 74.2% (23/31) of other rectal SELs were classified correctly as non-NENs. Eight cases of other SELs were misdiagnosed as NENs, including two cases of inflammatory lesions and one case each of gastrointestinal tumor, endometriosis, metastatic tumor, lymphoma, neurilemmoma, and hemangioma. The positive predictive value of EUS for rectal NENs was 80.9% (34/42), the negative predictive value was 92.0% (23/25), and the diagnostic accuracy was 85.1%.

CONCLUSION: EUS has satisfactory diagnostic accuracy for rectal NENs with good sensitivity, but unfavorable specificity, making the differential diagnosis of NENs from other SELs challenging.

Core tip: Distinguishing other subepithelial lesions (SELs) from neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) is important for appropriate clinical management of the disease. In this study, the typical endoscopic ultrasonographic (EUS) characteristics of rectal NENs are round or nodular homogeneous medium-echoic lesions located in both the second and third wall layers clearly demarcated from the surrounding tissue. Approximately 94.4% of rectal NENs were correctly diagnosed by EUS, but 25.8% of other rectal SELs were misdiagnosed as NENs. EUS has satisfactory diagnostic accuracy for rectal NEN with good sensitivity, but unfavorable specificity, making the differential diagnosis of NENs from other SELs challenging.

- Citation: Chen HT, Xu GQ, Teng XD, Chen YP, Chen LH, Li YM. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography for rectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(30): 10470-10477

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i30/10470.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10470

In the first decade of this century, there was an increased incidence of digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs), perhaps due to the extensive application of endoscopic procedures and imaging investigations[1-4]. According to the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2011 consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive NEN, NENs were defined to embrace the whole family of low-, intermediate- and high-grade tumors. Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) represent low- to intermediate-grade neoplasms, which were previously defined as either “carcinoid” or “atypical carcinoid”; neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) represents only high-grade neoplasms, previously defined as poorly differentiated carcinomas[5].

The rectum is one of the most frequent sites of digestive NENs. Rectal NENs have rapidly increased in incidence, with more than a 10-fold rise in the last 30 years[6]. The treatment of rectal NENs depends on the tumor size and depth[6]. Recent consensus guidelines on the management of rectal NENs suggest that small tumors (< 1-2 cm) confined to the mucosa or submucosa can be managed by endoscopic resection due to their low risk of metastatic spread[7,8]. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was found to be useful for measuring the size and depth of rectal NENs, which is essential for determining appropriate treatment[9-12]. In addition, the preoperative diagnosis of rectal NENs may be more important due to its malignant potential.

Although the majority of rectal subepithelial lesions (SELs) are NENs, a wide spectrum of other tumors, such as gastric small gastrointestinal tumor (GIST), lymphangioma, lymphoma, and metastatic tumor, and non-tumor conditions including endometriosis, duplication cyst, and inflammatory lesions, may arise in the rectum and the perirectal region[13]. These lesions can produce symptoms similar to those caused by NENs, such as diarrhea, hematochezia, or change in bowel habits. Distinguishing these SELs from NENs is of crucial importance for appropriate clinical management. However, the sonographic features of rectal NENs and other SELs require further research[14] and the diagnostic value of EUS has not been well established due to the rareness of these diseases. Thus, we explored the diagnostic accuracy of EUS for rectal NENs and the sonographic distinction between NENs and other SELs.

The study group consisted of 36 consecutive patients with rectal NENs who underwent preoperative EUS examination at the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China, from January 2007 to December 2013. The NEN group was composed of 21 males and 15 females, aged from 32 to 77 years, with a mean age of 53.6 years. Prior to EUS, all tumors had been detected by colonoscopy. Thirteen patients underwent colonoscopy due to focal symptoms, such as diarrhea, constipation and mucosanguineous feces, while the remaining patients without relative clinical manifestations underwent colonoscopy for other reasons. All patients with rectal NENs did not have carcinoid syndrome. With the exception of one patient who had hepatic metastasis, all patients underwent either surgery (9 cases), endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR, 8 cases) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD, 18 cases). The diagnosis of rectal NENs in all patients was histopathologically established using biopsy and/or resected specimens. Grading was available in 35 (97.2%) cases, and G1 tumors accounted for 88.9% (n = 32), G2 8.3% (n = 3), and G3 2.8% (n = 1) according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification.

The control group consisted of 31 homochronous patients with rectal non-NEN SELs confirmed by pathology. Epithelial lesions such as cancer and adenoma were excluded from this study. The 31 rectal non-NEN SELs included GISTs in 6 cases, endometriosis in 6 cases, inflammatory lesions in 5 cases, metastatic tumor in 4 cases, lymphangioma in 2 cases, lymphoma in 2 cases, leiomyoma in 1 case, neurilemmoma in 1 case, hemangioma in 1 case, hamartoma in 1 case, cystic rectal duplication in 1 case and tailgut epidermoid cyst in 1 case.

The EUS system included Olympus EU-M2000 and EU-ME 1 sonogram processing equipment, an Olympus CF-Q260AI electronic colonoscope, Olympus MAJ drive systems with a high-frequency echo probe, UM-DP12-25R miniature ultrasonic probes with a frequency of 12 MHz, and a Daker WP-800 water pump (Olympus Medical System Corp., Tokyo Japan).

After rectal SELs were detected by colonoscopy, EUS was performed using the degassing and water filling method to obtain sonographic images. Five well-trained endoscopists performed the EUS examinations. To exclude interobserver bias due to differences in EUS experience between the endoscopists, one EUS expert blinded to the histological results reviewed the ultrasonic images of all rectal SELs collected from the database. The size, original layer, echoic intensity and homogeneity of the lesions and the perifocal structures were investigated. The diagnostic standard for rectal NENs by EUS was defined as round or egg-shaped lesions with a hypoechoic or intermediate homogeneous echo pattern, well demarcated and mainly located in the second and/or third wall layer (mucosa and/or submucosa)[11]. A single EUS diagnosis was recorded by the EUS expert.

Patient demographics and characteristics of rectal NENs in EUS were analyzed. Summary statistics including mean size and depth as well as accuracy were determined for the lesions. The diagnostic accuracy of EUS was determined by comparing the endoscopist’s impression on the electronic procedure report with histologic findings. Statistical indices to evaluate the efficiency of the diagnostic test were calculated.

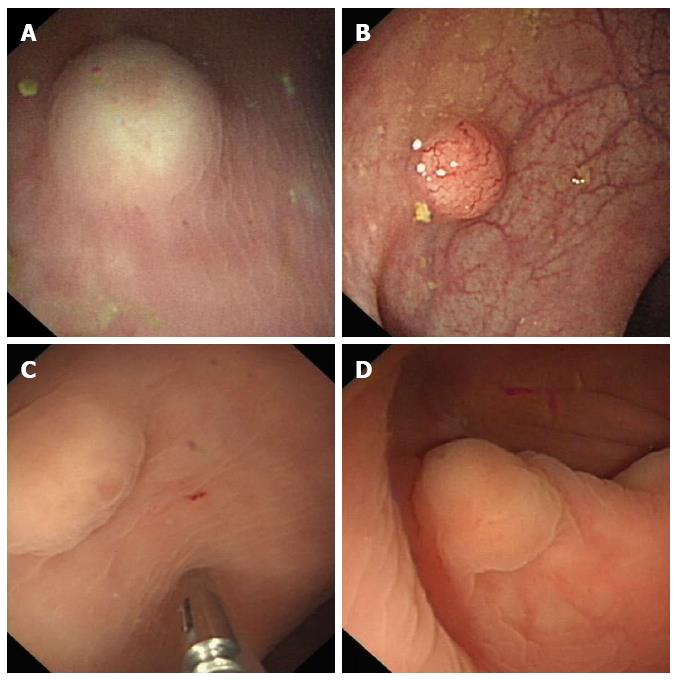

All NENs were located at the rectum 2-10 cm from the anus and presented as SELs. The NENs were seen as hemispherical bulges (Figure 1A, B) in 23, hummocky (Figure 1C) in 10 and flat-shaped bulges (Figure 1D) in 3 patients. Eleven tumors were yellowish (Figure 1A, B) and the others were similar in color to the surrounding mucosa. The mucosa covering the tumors was erosive (Figure 1C) in 5 cases and intact in the others. The surface of the tumors was reddish (Figure 1A) in 3 cases and had the appearance of a pyknic vascular net (Figure 1B) in 7. Prior to EUS, a definite diagnosis of NENs had been established by routine endoscopic biopsy in only 4 cases.

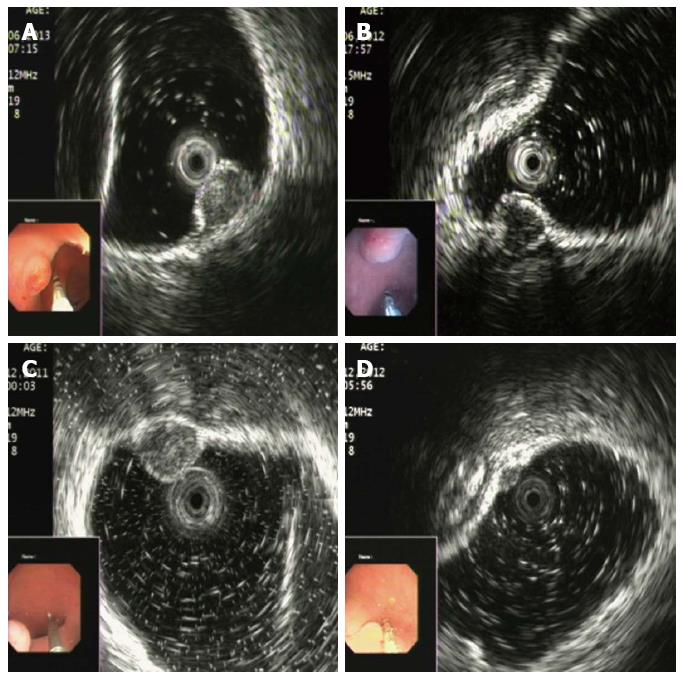

Rectal NENs appeared as nodular (n = 12), round (n = 19) or egg-shaped (n = 5) lesions with a hypoechoic (n = 7) or intermediate (n = 29) echo pattern with a distinct border (Figure 2). Tumors ranged in size from 2.3 to 13.7 mm, with an average size of 6.8 mm. Homogeneous echogenicity was seen in all tumors except 3. Apart from 3 patients (2 stage T2 and 1 stage T3), the tumors were located in the second and/or third wall layer without involvement of the fourth and fifth layers. Among the patients with stage T1, the tumors were located in the second wall layer only (Figure 2A) in 7, the third wall layer only (Figure 2B, C) in 2, and both the second and third wall layers in 27 (Figure 2D).

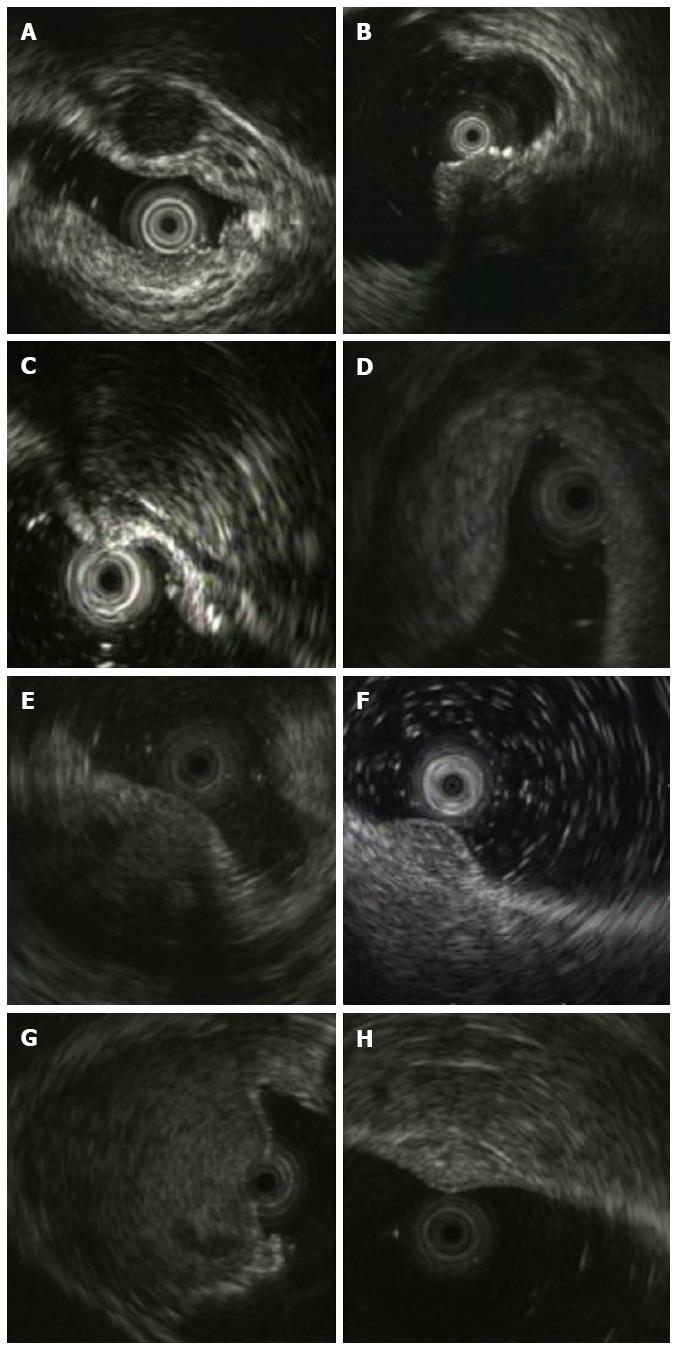

The diagnostic results by EUS and pathology in 67 cases of rectal SELs are shown in Table 1. Approximately 94.4% (34/36) of rectal NENs were diagnosed correctly by EUS, and the remaining two NENs were misdiagnosed as GIST (Figure 2B, hypoechoic within the third layer) and lipoma (Figure 2C, intermediate echo within the third layer), respectively. Twenty-three (74.2%) of 31 other rectal SELs were classified correctly as non-NENs. Eight cases of other SELs were misdiagnosed as NEN, including two cases of inflammatory lesions and one case each of GIST, endometriosis, metastatic tumor, lymphoma, neurilemmoma, and hemangioma (Figure 3). Their EUS characteristics are summarized in Table 2. As shown in Table 1, the positive predictive value of EUS for rectal NENs was 80.9% (34/42), the negative predictive value was 92.0% (23/25), the positive likelihood ratio was 3.6606, negative likelihood ratio was 0.0749, the diagnostic accuracy was 85.1%, and the Youden index was 0.686. The prevalence rate of NENs in rectal SELs was 53.7%.

| EUS diagnosis | Pathologic diagnosis | Total | |

| NEN | Non-NEN | ||

| NEN | 34 | 8 | 42 |

| Non-NEN | 2 | 23 | 25 |

| Total | 36 | 31 | 67 |

| Case | Pathology result | EUS features | |||||

| Layer | Size (mm) | Shape | Border | Echogenicity | Homogeneity | ||

| 1 | Stromal tumor | 3rd | 8 | Round | Distinct | Hypoechoic | Homogenous |

| 2 | Endometriosis | Full-thickness | 35 | Irregular | Blurry | Hypoechoic | Heterogeneous |

| 3 | Inflammatory node | 3rd | 5 | Nodous | Blurry | Hyperecho | Heterogeneous |

| 4 | Inflammatory lesion | 3rd | 20 | Spindle | Blurry | Hyperecho | Heterogeneous |

| 5 | Metastatic carcinoma | 3rd-4th-5th | 12 | Round | Blurry | Hypoechoic | Heterogeneous |

| 6 | Lymphoma | 2nd-3rd-4th | 6 | Spindle | Blurry | hypoechoic | Heterogeneous |

| 7 | Neurilemmoma | 2nd-3rd-4th | 34 | Round | Distinct | Intermediate | Heterogeneous |

| 8 | Hemangioma | 3rd | 9 | Oval | Distinct | Hyperecho | Honeycomb |

NENs are morphologically and biologically heterogeneous tumors that have malignant potential, and are most commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract. The rectum is the third most common location for gastrointestinal NENs[15]. Rectal NENs, often detected incidentally during colonoscopy, are typically small, localized, non-functioning tumors which are rarely metastatic[16,17] and can be treated by minimally invasive endoscopic resection when limited to the superficial layers of the bowel wall[18]. The preoperative diagnosis of rectal NENs may be challenging due to the absence of specific clinical manifestations and biochemical indicators. Although gastrointestinal NENs are epithelial tumors arising from the mucosa, they penetrate the muscularis mucosa and invade the submucosa at an early stage[19], where they go on to grow and proliferate in the submucosal layer. Thus, gastrointestinal NENs macroscopically resemble submucosal tumors[19] and there is little opportunity to make a conclusive pathologic diagnosis by endoscopic biopsy.

EUS has been reported to be an effective modality for assessing gastrointestinal tumors and allowing evaluation of the original layer of the submucosal tumor, the homogeneity of the internal parenchymal echo, and the echogenicity of the lesions[20]. In 1993, Yoshikane et al[10] reported that the internal echo of gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors (5 gastric, 7 duodenal and 17 rectal) was generally hypoechoic and homogeneous, the margins were clearly visualized and the contour was smooth. The tumors were mainly located in the third layer. The second layer covered the tumor with the third layer at its base, and it abutted the tumor and became indistinct near its upper interface. However, the advent of high frequency devices (12 and 20 MHz) has provided better resolution, enabling detailed imaging of the interior of even small lesions. In 2005, Kobayashi et al[19] performed EUS in 53 cases of rectal carcinoid tumors, and distinct images were obtained in 52 (98%) lesions. Forty-seven (90%) of 52 lesions successfully imaged by EUS had a homogenous, isoechoic-to-hypoechoic internal echo. The tumors were clearly demarcated from the surrounding tissue. In fact, the echogenicity of isoechoic lesions, close to the echo of the second layer, had a medium echo level between the third layer (hyperechoic) and fourth layer (hypoechoic). In our study, 80.6% (29/36) of rectal NENs appeared medium-echoic and only 19.4% (7/36) appeared hypoechoic; 75% (27/36) of tumors were located in both the second and third wall layers without involvement of the fourth layer. Thus, we believe that the typical EUS characteristics of rectal NENs are round or nodular homogeneous medium-echoic lesions located in both the second and third wall layers clearly demarcated from the surrounding tissue.

Epithelial lesions, such as rectal cancer and adenoma, were excluded from this study as they have a different endoscopic appearance from NENs and a high rate of definite diagnosis by routine biopsy. Rectal SELs are rare and difficult to distinguish from each other by colonoscopy. EUS is useful in the diagnosis of SELs of the large intestine as it provides precise information on these lesions[21]. In our study, 94.4% of rectal NENs were correctly diagnosed by EUS with a negative predictive value of 92.0%. Thus, we believe that EUS is a very sensitive diagnostic method for rectal NENs. Both of the misdiagnosed cases of NENs had the same original layer (submucosa alone) and quasi-echogenicity with GIST or lipoma. In contrast to the good diagnostic sensitivity and negative predictive value of EUS, the specificity (74.2%) was lower, with an unfavorable positive predictive value of 80.9%. Eight (25.8%) of 31 other rectal SELs were misdiagnosed as NENs. Non-NEN SELs in this study included GISTs, enteric endometriosis, inflammatory lesions, metastatic tumors, lymphangiomas, lymphomas, leiomyoma, neurilemmoma, hemangioma, hamartoma, cystic rectal duplication and tailgut epidermoid cyst. The echogenicity of these non-NEN SELs may be confused with NENs, with the exception of lymphangioma and tailgut epidermoid cyst. Therefore, the differential diagnosis of rectal NENs from other SELs by EUS is challenging.

The most common site of extragenital endometriosis is the wall of the sigmoid colon and rectum. On EUS examination, the endometriotic implants were reported as hypoechoic lesions, with irregular and undefined margins, infiltrating the muscularis propria and the serosa, but not the mucosa/submucosa of the rectal wall, and extending outside the rectal wall[22,23]. In our study, 5/6 cases of enteric endometriosis infiltrated the muscularis propria and the serosa, but spared the mucosa and submucosa of the rectal wall, while the other was erroneously identified as NEN due to full-thickness infiltration.

Metastases to the rectal wall are rare and often present as rectal linitis plastica secondary to gastric, bladder and prostate carcinomas[24,25]. In this series, 3/4 cases of metastases to the rectal wall presented as rectal linitis plastica, but one case presented as a SEL mimicking NEN with local infiltration in the rectal wall. Lymphoma of the rectum shows mostly, elevated lesions, such as polyps or subepithelial tumors[26]. In the two cases of lymphoma in this series, EUS detected a homogenous hypoechoic lesion confined to the mucosal layer of the rectal wall in one and a heterogeneous hypoechoic lesion infiltrating the 2nd-3rd-4th layers in another which was misdiagnosed as NEN.

Although most GISTs originate from the fourth layer of the rectal wall, a few GISTs originate from the third layer, whose differential diagnosis with NENs may be difficult by EUS. Inflammatory nodules confined to the third layer may also be misdiagnosed as NENs. Neurilemmoma and hemangioma in the rectum are rare and their EUS characteristics are undefined. In our series, an irregular anechoic area representing necrosis and a honeycomb echo denoting sinusoidal blood may be their respective typical EUS findings.

In summary, the EUS characteristics of rectal NENs are round or nodular homogeneous medium-echoic lesions located in both the second and third wall layer clearly demarcated from the surrounding tissue. EUS has satisfactory diagnostic accuracy for rectal NENs with good sensitivity, but unfavorable specificity, making the differential diagnosis of NENs from other SELs challenging.

There has been a worldwide increase in the incidence of digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs). NENs may be low- to intermediate-grade neoplasms, or high-grade neoplasms. The rectum is one of the most frequent sites of digestive NENs. The treatment of rectal NENs depends on the tumor size and depth. Small tumors (< 1-2 cm) confined to the mucosa or submucosa can be managed by endoscopic resection due to their low risk of metastatic spread. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is useful for measuring the size and depth of rectal NENs, which is essential for appropriate treatment choice.

The preoperative diagnosis of rectal NENs is important due to its malignant potential. Although the majority of rectal subepithelial lesions (SELs) are NENs, a wide spectrum of other tumors and non-tumor conditions including endometriosis, duplication cyst, and inflammatory lesions, may occur in the rectum. These lesions can cause symptoms similar to those caused by NENs, such as diarrhea, hematochezia, or change in bowel habits. Distinguishing these SELs from NENs is of crucial importance for appropriate clinical management.

This study showed that the typical EUS characteristics of rectal NENs were round or nodular homogeneous medium-echoic lesions located in both the second and third wall layers clearly demarcated from the surrounding tissue. Approximately 94.4% of rectal NENs were diagnosed correctly by EUS and 74.2% (23/31) of other rectal SELs were classified correctly as non-NENs. The SELs misdiagnosed as NENs included inflammatory lesions, gastric small gastrointestinal tumors, endometriosis, metastatic tumor, lymphoma, neurilemmoma, and hemangioma. The positive predictive value of EUS for rectal NENs was 80.9%, the negative predictive value was 92.0%, the positive likelihood ratio was 3.6606, negative likelihood ratio was 0.0749, the diagnostic accuracy was 85.1%, and the Youden index was 0.686. The prevalence rate of NENs in rectal SELs was 53.7%.

EUS has satisfactory diagnostic accuracy for rectal NENs with good sensitivity, but unfavorable specificity, making the differential diagnosis of NEN from other SELs challenging.

EUS is an effective imaging modality for assessing gastrointestinal lesions and allowing evaluation of the original layer of submucosal lesions, the homogeneity of the internal parenchymal echo, and the echogenicity of the lesions. Rectal NENs originate from neuroendocrine cells, which have limited invasion and infiltration in the deep rectal crypt. Compared with other tumors, the rate of lymphatic and hematogenous metastases was low.

It is an interesting topic. Controlled clinical trials with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are necessary to evaluate the technique.

P- Reviewer: Delgado JS, Giudici F, Otegbayo JA S- Editor: Nan J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Lepage C, Rachet B, Coleman MP. Survival from malignant digestive endocrine tumors in England and Wales: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:899-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, Abdalla EK, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Rashid A. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063-3072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3022] [Cited by in RCA: 3247] [Article Influence: 191.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Niederle MB, Hackl M, Kaserer K, Niederle B. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: the current incidence and staging based on the WHO and European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society classification: an analysis based on prospectively collected parameters. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Garcia-Carbonero R, Capdevila J, Crespo-Herrero G, Díaz-Pérez JA, Martínez Del Prado MP, Alonso Orduña V, Sevilla-García I, Villabona-Artero C, Beguiristain-Gómez A, Llanos-Muñoz M. Incidence, patterns of care and prognostic factors for outcome of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs): results from the National Cancer Registry of Spain (RGETNE). Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1794-1803. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Salazar R, Wiedenmann B, Rindi G, Ruszniewski P. ENETS 2011 Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Digestive Neuroendocrine Tumors: an update. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:71-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1-18, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Choi HH, Kim JS, Cheung DY, Cho YS. Which endoscopic treatment is the best for small rectal carcinoid tumors? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:487-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Anthony LB, Strosberg JR, Klimstra DS, Maples WJ, O’Dorisio TM, Warner RR, Wiseman GA, Benson AB, Pommier RF. The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (nets): well-differentiated nets of the distal colon and rectum. Pancreas. 2010;39:767-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, Maruyama M, Matsuda M, Setoyama T, Suzuki S, Uchida S, Uemura M, Iizuka Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1413-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoshikane H, Tsukamoto Y, Niwa Y, Goto H, Hase S, Mizutani K, Nakamura T. Carcinoid tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: evaluation with endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:375-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | De Angelis C, Carucci P, Repici A, Rizzetto M. Endosonography in decision making and management of gastrointestinal endocrine tumors. Eur J Ultrasound. 1999;10:139-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou FR, Huang LY, Wu CR. Endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal carcinoids under micro-probe ultrasound guidance. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2555-2559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Purysko AS, Coppa CP, Kalady MF, Pai RK, Leão Filho HM, Thupili CR, Remer EM. Benign and malignant tumors of the rectum and perirectal region. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39:824-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu J, Wang ZQ, Zhang ZQ, Chen X, Zhang Y. Evaluation of colonoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors with diameter less than 1 cm in 21 patients. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1667-1671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wang AY, Ahmad NA. Rectal carcinoids. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Ni SJ, Sheng WQ, Du X. Pathologic research update of colorectal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1713-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Boškoski I, Volkanovska A, Tringali A, Bove V, Familiari P, Perri V, Costamagna G. Endoscopic resection for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:559-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kobayashi K, Katsumata T, Yoshizawa S, Sada M, Igarashi M, Saigenji K, Otani Y. Indications of endoscopic polypectomy for rectal carcinoid tumors and clinical usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okanobu H, Hata J, Haruma K, Mitsuoka Y, Kunihiro K, Manabe N, Tanaka S, Chayama K. A classification system of echogenicity for gastrointestinal neoplasms. Digestion. 2005;72:8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kameyama H, Niwa Y, Arisawa T, Goto H, Hayakawa T. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of submucosal lesions of the large intestine. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:406-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mezzi G, Ferrari S, Arcidiacono PG, Di Puppo F, Candiani M, Testoni PA. Endoscopic rectal ultrasound and elastosonography are useful in flow chart for the diagnosis of deep pelvic endometriosis with rectal involvement. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37:586-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pishvaian AC, Ahlawat SK, Garvin D, Haddad NG. Role of EUS and EUS-guided FNA in the diagnosis of symptomatic rectosigmoid endometriosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:331-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gleeson FC, Clain JE, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Wang KK, Wiersema MJ, Zhang L, Levy MJ. Secondary linitis plastica of the rectum: EUS features and tissue diagnosis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:591-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dumontier I, Roseau G, Palazzo L, Barbier JP, Couturier D. Endoscopic ultrasonography in rectal linitis plastica. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:532-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ahlawat S, Kanber Y, Charabaty-Pishvaian A, Ozdemirli M, Cohen P, Benjamin S, Haddad N. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma occurring in the rectum: a case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2006;99:1378-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |