INTRODUCTION

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare benign disorder characterized by a combination of symptoms, endoscopic findings, and histological abnormalities[1]. It was first described by Cruveihier[2] in 1829, when he reported four unusual cases of rectal ulcers. The term “solitary ulcers of the rectum” was used by Lloyd-Davis in the late 1930s and in 1969 the disease became widely recognized after a review of 68 cases by Madigan et al[3], and few years later, a more comprehensive pathogenic concept of the disease was reported by Rutter et al[4]. SRUS is an infrequent and underdiagnosed disorder, with an estimated annual prevalence of one in 100000 persons. It is a disorder of young adults, occurring most commonly in the third decade in men and in the fourth decade in women. Men and women are affected equally, with a small predominance in women[5]. However, it has been described in children and in the geriatric population[6]. Solitary rectal ulcer is a misnomer because ulcers are found in 40% of patients, while 20% of patients have a solitary ulcer, and the rest of the lesions differ in shape and size, including hyperemic mucosa to broad-based polypoid lesions[7]. There is even a suggestion that the disease process also may involve the sigmoid colon[8].

In addition, the etiology is not known but may involve a number of mechanisms. For example, ischemic injury from pressure of impacted stools and local trauma due to repeated self-digitation may be contributing factors[9]. Furthermore, opinion differs regarding the best treatment for this troublesome condition, varying from conservative management and enema preparations to more invasive surgical procedures such as rectopexy[10]. In this mini-review, several aspects of this syndrome are evaluated, and detailed information about the disease will help guide future prevention and treatment strategies.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

SRUS is a chronic, benign, underdiagnosed disorder characterized by single or multiple ulcerations of the rectal mucosa, with the passage of blood and mucus, associated with straining or abnormal defecation[11]. The average time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis is 5 years, ranging from 3 mo to 30 years in adults, which is longer than in pediatric patients (1.2-5.5 years)[12]. Clinical features include rectal bleeding, copious mucus discharge, prolonged excessive straining, perineal and abdominal pain, feeling of incomplete defecation, constipation, and rarely, rectal prolapse[13,14]. The amount of blood varies from a little fresh blood to severe hemorrhage that requires blood transfusion[15]. Some children present with apparent diarrhea (because of prolonged visits to the bathroom), and associated bleeding, abdominal pain, and tenesmus suggest to clinicians the presence of inflammatory bowel disease[16]. However, it is unusual that a child may present with recurrent rectal bleeding and anemia requiring blood transfusion[6]. Although the passage of blood during defecation is the hallmark, up to 26% of patients can be asymptomatic, discovered incidentally when investigating other diseases[7].

The underlying etiology and pathogenesis are not fully understood but multiple factors may be involved. The most accepted theories are related to direct trauma or local ischemia as causes. It has been suggested that descent of the perineum and abnormal contraction of the puborectalis muscle during straining on defecation or defecation in the squatting position result in trauma and compression of the anterior rectal wall on the upper anal canal, and internal intussusceptions or prolapsed rectum[6,17]. Mucosal prolapse, overt or occult, is the most common underlying pathogenetic mechanism in SRUS. This may lead to venous congestion, poor blood flow, and edema in the mucosal lining of the rectum and ischemic changes with resultant ulceration. The cause of ischemia may also be related to fibroblasts replacing blood vessels, and pressure by the anal sphincter. Moreover, rectal mucosal blood flow has been found to be reduced in SRUS to a level similar to that seen in normal transit constipation, suggesting similar impaired autonomic cholinergic gut-nerve activity[18]. Self-digitation maneuver to reduce rectal prolapse or to evacuate an impacted stool may also cause direct trauma of the mucosa and ulceration[19]. Although this hypothesis seems plausible, it remains unproven because rectal mucosal intussusception is common even in healthy subjects, but rectal prolapse and SRUS are rare[20]. In addition, not all patients with rectal prolapse have SRUS and vice versa[21]. Furthermore, ulcers usually occur in the mid rectum, which can not be reached by digital examinations[22]. Hence, it has been suggested that rectal prolapse and SRUS are two disparate conditions. In children, secondary to chronic mechanical and ischemic trauma, inflammation by hard stools, and intussusceptions of the rectal mucosa, some histological features of SRUS can be seen, such as fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria and disorientation of muscle fibers[23].

Anorectal physiology studies have shown that 25%-82% of patients with SRUS may have dyssynergia with paradoxical anal contraction[24]. Studies have confirmed that uncoordinated defecation with excessive straining over time play a key role in SRUS[19]. Morio and his colleagues found that SRUS patients compared with three control groups (dyssynergic defecation alone, rectal prolapse with or without mucosal changes) had more frequent increase in anal pressure and paradoxical puborectalis contraction during strain[25]. In addition, a case-control study showed that up to 82% of subjects exhibited dyssynergia along with prolonged balloon expulsion time[19]. Also, SRUS patients exhibited rectal hypersensitivity, raising the hypothesis that hypersensitivity may lead to a persistent desire to defecate and/or feeling of incomplete evacuation and excessive straining.

DIAGNOSIS

The cause of SRUS is unknown. The clinical presentation varies, therefore, early diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion from both the surgeon and the pathologist[7,20], especially because the term “solitary rectal ulcer” is a misnomer and only a quarter of the adults with SRUS have a true rectal ulcer, and the lesion is not necessarily solitary or ulcerated[26]. Diagnosis of SRUS is based on clinical features, findings on proctosigmoidoscopy and histological examination, imaging investigations including defecating proctography, dynamic magnetic resonance imaging, and anorectal functional studies including manometry and electromyography[27]. A complete and thorough history is most important in the initial diagnosis of SRUS. Differential diagnosis includes Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, ischemic colitis, and malignancy. Obstructive symptoms in children may be interpreted by parents as constipation. In a quarter of patients, a delay in diagnosis or misdiagnosis of SRUS might occur because of inadequate rectal biopsy and failure to recognize the histopathological features of the disease[27]. Concomitant hematochezia may be misinterpreted as originating from an anal fissure caused by constipation, or as other causes of rectal bleeding such as a juvenile polyp[11,28].

Colonoscopy and biopsy of normal and abnormal-looking rectal and colonic mucosa should be performed. It has been reported that the ulcer is usually located on the anterior wall of the rectum and the distance of the ulcer from the anal margin varies from 3 to 10 cm[3]. Ulcers may range from 0.5 to 4 cm in diameter but are usually 1-1.5 cm[29]. The appearance of SRUS on endoscopy may vary from preulcer hyperemic changes of rectal mucosa to established ulcers covered by a white, grey or yellowish slough[3,29] (Figure 1A). The ulceration is shallow and the adjacent mucous membrane may appear nodular, lumpy or granular[30]. Twenty-five percent of SRUSs may appear as a polypoid lesion; 18% may appear as patchy mucosal erythema; and 30% as multiple lesions. As a result of the wide endoscopic spectrum of SRUS and the fact that the condition may go unrecognized or, more commonly, misdiagnosed, it is crucial to collect biopsy specimens from the involved area to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude other diagnoses, including cancer[5]. Defecography is a useful method for determining the presence of intussusception or internal or external mucosal prolapse and can demonstrate a hidden prolapse, as well as a non-relaxing puborectalis muscle and incomplete or delayed rectal emptying[31]. However, because of the wide availability of endoscopy and biopsy, defecography usually is reserved for the investigation of the underlying pathophysiology and possibly for preoperative assessment[32]. Barium enema shows granularity of the mucosa, polypoid lesion, rectal stricture and ulceration, and thickened rectal folds; all of which are nonspecific findings[33]. It has been recommended that defecography and anorectal manometry should be performed in all children with SRUS to define the primary pathophysiological abnormality and to select the most appropriate treatment protocol[34]. Anorectal manometry and electromyography provide useful information about anorectal inhibitory reflex, pressure profiles, defecation dynamics, and rectal compliance and sensory thresholds. On awake anorectal manometry, 42%-55% of children with chronic constipation show dyssynergia and abnormal contraction of voluntary muscles of the pelvic floor and external anal sphincters (EASs) during an attempt to expel a rectal balloon[35]. In adults, excessive straining and uncoordinated defecation, caused by dyssynergia of pelvic floor muscles, are attributed to development of SRUS[36]. These all suggest a relationship between dyssynergia of the pelvic floor and the EAS muscles, constipation, rectal prolapse, and SRUS. Recent studies have shown the usefulness of anorectal ultrasound in assessing internal anal sphincter thickness, which is increased in patients with SRUS[37], and it has been suggested that sonographic evidence of a thick internal anal sphincter is highly predictive of high-grade rectal prolapse and intussusceptions[38]. Routine laboratory tests including red and white blood cell counts, platelet count, hemoglobin, liver function tests, coagulation tests, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are usually normal. Features of microcytic anemia with low values of hemoglobin, hematocrit and mean corpuscular volume may, however, be seen in a child with a history of recurrent bleeding per rectum[35].

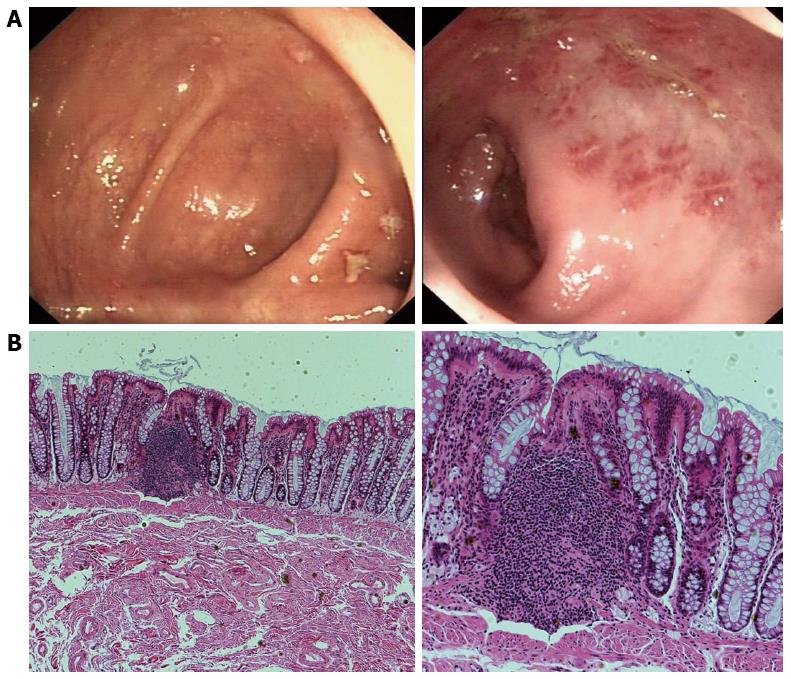

Figure 1 Endoscopic imaging and corresponding histological findings in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome patients.

A: Colonoscopy revealed localized yellowish slough, rectal edema, erythema, and superficial ulcerations; B: Histology (hematoxylin and eosin) shows smooth muscle hyperplasia in the lamina propria between colonic glands, and surface ulceration with associated chronic inflammatory infiltrates. Magnification: × 40 (left), × 100 (right).

Key histological features include fibromuscular obliteration of the lamina propria, hypertrophied muscularis mucosa with extension of muscle fibers upwards between the crypts, and glandular crypt abnormalities[39] (Figure 1B). Other minor microscopic changes, including surface erosion (which is covered by mucus, pus and detached epithelial cells, and may show reactive hyperplasia with distortion of the crypt architecture), mild inflammation, distorted crypts, and reactive epithelial atypia, may lead to erroneous diagnoses such as inflammatory bowel disease (which may show chronic and acute inflammatory cells in lamina propria, cryptitis, crypt abscesses and granuloma formation, with distortion of epithelial and glandular structures) and cancer[40]. Diffuse collagen deposition in the lamina propria and abnormal smooth muscle fiber extensions are sensitive markers for differentiating SRUS from other conditions[41].

TREATMENT

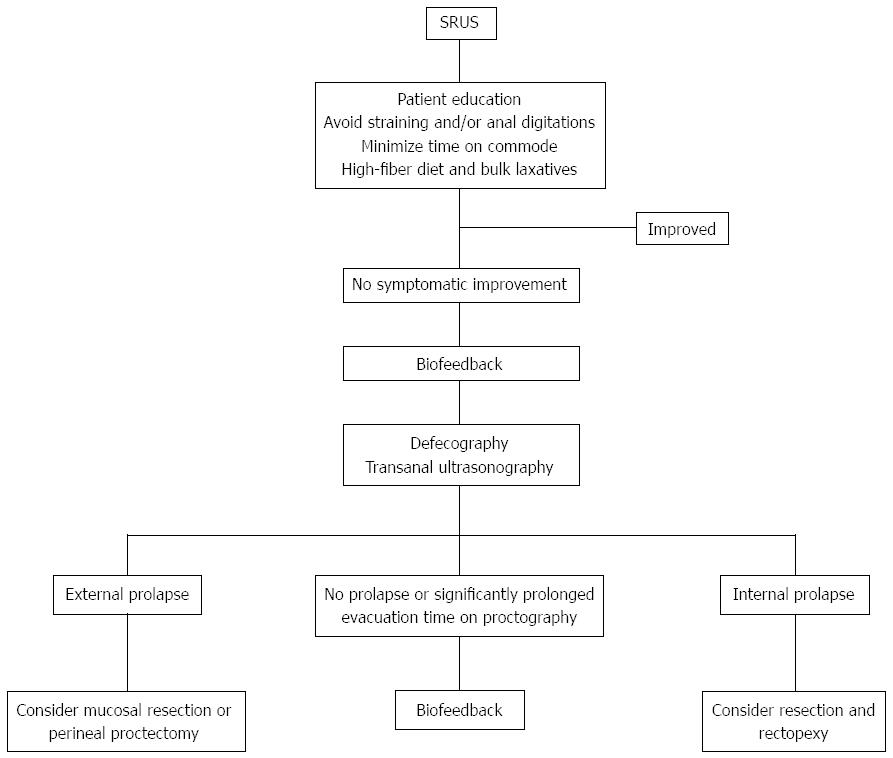

Several treatment options have been used for SRUS, ranging from conservative treatment (i.e., diet and bulking agents), medical therapy, biofeedback and surgery (Figure 2). The choice of treatment depends upon the severity of symptoms and whether there is a rectal prolapse.

Figure 2 Suggested algorithm for treatment strategies in patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

SRUS: Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome.

Patient education and behavioral modification are the first steps in the treatment of SRUS[9]. In particular, asymptomatic patients may not require any treatment other than behavioral modifications. Other suggestions for the treatment include reassurance of the patient that the lesion is benign, encouragement of a high-fiber diet, avoidance of straining, regulation of toilet habits, and attempt to discuss any psychosocial factors[42]. The use of a high-fiber diet, in combination with stool softeners and bulking laxatives, and avoidance of straining have had varying responses[43]. These dietary and behavioral modifications are especially effective in patients with mild to moderate symptoms and with absence of significant mucosal prolapse. However, it would appear that conservative approaches are less useful when SRUS is associated with an advanced grade of rectal intussusception, extensive inflammation, established fibrosis and/or reducible external prolapse[44]. Therefore, in patients whose symptoms are resistant to those conservative measures, a more organized form of behavioral therapy such as biofeedback appears promising. It has been suggested that, in selected patients, biofeedback improves symptoms by altering efferent autonomic pathways to the gut[45]. Biofeedback includes reducing excessive straining with defecation by correcting abnormal pelvic-floor behavior and by attempting to stop the aid of laxatives, suppositories, and enemas[46]. In a case-control study, standard biofeedback therapy improved both anorectal function and bowel symptoms in most patients who exhibited dyssynergic defecation[19]. Furthermore, the improvement in symptoms and manometric findings was associated with significant healing in 54% of patients. In another study, Jarrett and his colleagues found that 12/16 (75%) patients with SRUS had subjective improvement after biofeedback, and this was associated with increased rectal mucosal blood flow, suggesting that improved extrinsic innervation to the gut could be responsible for such a successful response[36]. Some authors suggest that biofeedback helps in the short term, but is less effective in the long term, and further systematic studies in a large population are required[42].

Topical treatments, including sucralfate, salicylate, corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, mesalazine and topical fibrin sealant, have been reported to be effective with various responses and improvement of symptoms[47]. Sucralfate enema contains aluminum complex salts, which coat the rectal ulcer and form a barrier against irritants, allowing the ulcer to heal. Corticosteroids and sulfasalazine enemas may also help ulcer healing by reducing the inflammatory responses. However, these treatments are empirical and have been applied in uncontrolled studies, and their long-term benefits deserve further investigation[48,49].

Surgery remains an option for patients not responsive to conservative measures and biofeedback. Surgery is warranted in almost one-third of adults with associated rectal prolapse; in children this has only been described in case reports[10]. Surgical treatments include excision of the ulcer, treatment of internal or overt rectal prolapse, and defunctioning colostomy[47]. The indication for surgery is failure of conservative treatment to control severe symptoms, and the aim is to avoid formation of colostomy as a primary operation. Sclerotherapy injection into the submucosa or retrorectal space with 5% phenol, 30% hypertonic saline or 25% glucose and perianal cerclage is effective in treating rectal prolapse. A therapeutic role of botulinum toxin injection into the external anal sphincter for the treatment of SRUS, and constipation associated with dyssynergia of defecation dynamics has also been reported by Keshtgar et al[50]. The effect of botulinum toxin lasts approximately 3 mo, which may be more beneficial than biofeedback therapy. In addition, in children, laparoscopic rectopexy using a polypropylene mesh on each side of the rectum, fixed to sacral promontory with a nonabsorbable structure, has been used successfully to treat SRUS[10]. Furthermore, for full-thickness prolapse, mucosal resection (Delorme’s procedure) or perineal proctectomy (Altemeier’s procedure) has been advocated[51]. In a series of 66 adult patients with SRUS, rectopexy was done in 49, Delorme’s operation in nine, restorative anterior resection in two, postanal repair and division of puborectalis in two, and primary colostomy in four[52]. Local excision of polypoid rectal ulcer and rectopexy for overt rectal prolapse, however, have a higher long-term cure rate[53]. Proctectomy may be required in patients with intractable rectal pain and bleeding, who have not responded to other surgical treatments[54]. Based on postoperative evacuation defecography studies, it has been shown that rectopexy alters rectal configuration and successfully treats rectal prolapse in SRUS, and that a prolonged preoperative evacuation time is predictive of poor symptomatic outcome[32]. When the above measures fail, mucosal-sleeve resection with coloanal pull-through or a diverting colostomy should be considered. The evidence regarding which approach is first-line for SRUS is unclear. However, open rectopexy and mucosal resection seem popular with a success rate of 42%-100%[55].

CONCLUSION

SRUS is a chronic, benign disorder in young adults, often related to straining or abnormal defecation. The pathogenesis of SRUS is not well understood, but may be multifactorial. Usually, patients present with straining, altered bowel habits, anorectal pain, incomplete passage of stools, and passage of mucus and blood. The diagnosis can be made clinically, endoscopically, and histologically. Symptoms may resolve spontaneously or may require treatment. A variety of therapies have been tried. Several therapies thought to be beneficial include topical medication, behavior modification supplemented by fiber and biofeedback, and surgery. Patient education and a conservative, stepwise individualized approach are important in the management of this syndrome.

P- Reviewers: Cerwenka HR, Hokama A, Nowicki MJ S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S