Published online Aug 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10183

Revised: February 13, 2014

Accepted: March 5, 2014

Published online: August 7, 2014

Processing time: 260 Days and 0.8 Hours

AIM: To compare the efficacy and safety of the transthoracic and transhiatal approaches for cancer of the esophagogastric junction.

METHODS: An electronic and manual search of the literature was conducted in PubMed, EmBase and the Cochrane Library for articles published between March 1998 and January 2013. The pooled data included the following parameters: duration of surgical time, blood loss, dissected lymph nodes, hospital stay time, anastomotic leakage, pulmonary complications, cardiovascular complications, 30-d hospital mortality, and long-term survival. Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding single studies.

RESULTS: Eight studies including 1155 patients with cancer of the esophagogastric junction, with 639 patients in the transthoracic group and 516 in the transhiatal group, were pooled for this study. There were no significant differences between two groups concerning surgical time, blood loss, anastomotic leakage, or cardiovascular complications. Dissected lymph nodes also showed no significant differences between two groups in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and non-RCTs. However, we did observe a shorter hospital stay (WMD = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.63-2.22, P < 0.00001), lower 30-d hospital mortality (OR = 3.21, 95%CI: 1.13-9.12, P = 0.03), and decreased pulmonary complications (OR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.95-4.45, P < 0.00001) in the transhiatal group. For overall survival, a potential survival benefit was achieved for type III tumors with the transhiatal approach.

CONCLUSION: The transhiatal approach for cancers of the esophagogastric junction, especially types III, should be recommended, and its long-term outcome benefits should be further evaluated.

Core tip: Surgical resection is the optimum therapy for cancer of the esophagogastric junction, and the transthoracic and transhiatal approaches are the two major surgical approaches used worldwide. However, considerable debate exists on the superior benefits of the two approaches regarding their efficacy and safety. We conducted this meta-analysis to address the issue. The results indicated a shorter hospital stay, lower 30-d hospital mortality and decreased pulmonary complications with the transhiatal approach compared with the transthoracic approach. Moreover, a potential survival benefit was achieved for type III tumors using the transhiatal approach.

-

Citation: Wei MT, Zhang YC, Deng XB, Yang TH, He YZ, Wang ZQ. Transthoracic

vs transhiatal surgery for cancer of the esophagogastric junction: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(29): 10183-10192 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i29/10183.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i29.10183

With the decreasing prevalence of gastric cancer, the incidence of cancer of the esophagogastric junction has rapidly risen in the past three decades, especially in North America and Europe[1]. Despite the use of chemotherapy, the 5-year survival rate is still low (less than 30%) for these cancers[2], and surgery remains the best therapeutic option. Based on the anatomic location of the tumors’ centers, Siewert’s classifications of types I to III provide universal evidence for the surgical approaches.

There are two major surgical approaches for cancer of the esophagogastric junction - the transthoracic approach (TT) and the transhiatal approach (TH). The TT approach aims to provide longer postoperative survival rates and en bloc resections of the tumor and lymph nodes, sometimes in combination with a thoracoabdominal resection. The TH approach results in fewer early operative complications and incomplete thoracic lymph node resection. Thus far, four reviews have compared the differences between these two approaches for cancers of the esophagus or distal esophagus[3-6], but not for cancers of the esophagogastric junction alone. Moreover, Stein et al[7] suggest that cancers of the esophagogastric junction should be considered an independent disease rather than a subset of esophageal or gastric cancer and that there is no standard surgical approach for this type of cancer. As a result, considerable debate on the superior benefits of these two approaches for the treatment of cancers of the esophagogastric junction persists.

To address the issue, we strictly reviewed articles comparing the transthoracic and transhiatal approaches for cancers of the esophagogastric junction. The pooled data included the following parameters: perioperative data (study population, pathological type, tumor stage and Siewert’s type, among others), surgery-related data (duration of surgical time, blood loss, hospital stay time and 30-d hospital mortality), dissected lymph nodes, complications (anastomotic leakage, pulmonary complications, and cardiovascular complications), and long-term survival.

This meta-analysis was conducted following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) to ensure data quality (Available from: URL: http://www.cochrane.org/training/cochrane-handbook).

A comprehensive search of the literature was electronically conducted in PubMed, EmBase and the Cochrane Library databases by combining the terms “tumor”, “esophagogastric junction”, “cardia”, “stomach”, “esophagus”, “transhiatal”, “transthoracic”, “transabdominal” and ”thoracoabdominal” using [Mesh] or [Keyword]. The search was limited to the period between March 1998 and April 2013. Furthermore, a manual search of the published articles in the related references was performed.

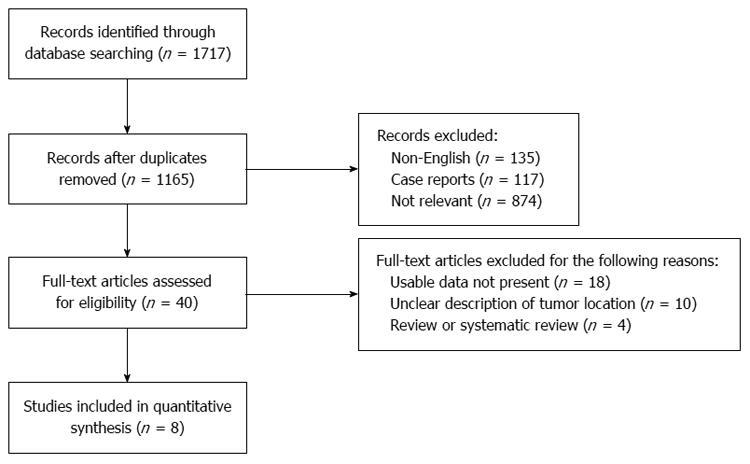

Study designs included randomized controlled (RCTs) studies, clinical controlled studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series. The flow chart of study selection was made following the PRISMA statement (Available from: URL: http://prisma-statement.org/statement.htm). The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) pathological diagnosis of the tumor as cancer of the esophagogastric junction; (2) location of the tumor in the cardia, not in the esophagus or stomach; (3) published studies comparing the two surgical strategies for cancer of the esophagogastric junction; and (4) available data on each group. The following exclusion criteria were included: (1) published studies with just one surgery strategy; (2) reported patients with mixed cardiac and esophageal cancers; (3) meta-analyses or case reports; and (4) published studies without available data.

Two investigators independently assessed the included studies according to the Cochrane Library handbook, and any disagreement was adjudicated by discussion or by consulting the corresponding author. Quality assessment of the randomized controlled trials was evaluated according to seven items: randomization, blinding, concealed allocation, baseline features, eligibility criteria, loss to follow-up, and selection bias. For non-randomized controlled studies, a modification of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) was used as an assessment tool for selection, comparability and outcome assessments. Out of a total of six scores, studies valued with more than four stars were recognized as being of moderate to high quality. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing a single trial.

The collected data included the following: (1) baseline characteristics of the patients, such as the study population, age, sex, tumor stage, pathological type, and Siewert’s type; and (2) outcomes, such as surgery-related data (duration of surgical time, blood loss, hospital stay time, and 30-d hospital mortality), dissected lymph nodes, complications (anastomotic leakage, pulmonary complications, and cardiovascular complications) and long-term survival.

The data were analyzed using Review Manager (Version 5.1). Weight mean differences (WMDs) and odds ratios (ORs) were used to analyze continuous data and dichotomous data, respectively. For survival analysis, we extracted data from survival curves by referring to methods reported in previous studies, and hazard ratios were used for quantitative analysis[8]. Heterogeneity was measured using the I2 index and P value. A random effect was used when the heterogeneity test had significance; otherwise, a fixed effect was used. Standard deviations (SD) were estimated using a formula when only a range was reported[9]: Estimate SD = Range/4 (15 < n < 70); Range/6 (n > 70). The value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; otherwise, no significance was attributed.

The study selection procedure is summarized in Figure 1. In this meta-analysis, three randomized controlled trials, two prospective studies and three retrospective studies were included, for a total of eight original articles[10-17] (Table 1). Among these, two studies[12,13] reported on the same patients with cancer of the esophagogastric junction, and the pooled data were integrated from both studies. In total, 1155 patients (639 patients in the TT group and 516 patients in the TH group) with cancer of the esophagogastric junction were included. There was no significance difference in the baseline data, including age (P = 0.20), sex (P = 1.00), or tumor stage (P = 0.97) of the two groups. All three RCTs were evaluated as superior trials (Table 2), and the other five non-RCTs were valued at moderate to high quality. Statistical heterogeneity was found in three outcomes: duration of surgical time, blood loss, and dissected lymph nodes. Sensitivity using the results excluding one trial did not alter the pooled estimation of the results of blood loss and dissected lymph nodes; however, the durations of surgical time were altered.

| Ref. | No. of patients | Age (mean ± SD or range) | Sex (M/F) | Siewert’s classification | Design | Country | |||

| TT | TH | TT | TH | TT | TH | ||||

| Gianotti et al[10] | 33 | 58 | 61/11 | 66/13 | 21/12 | 38/20 | II III | PS | Italy |

| Graham et al[11] | 32 | 119 | 63/(22-86) | 63/(22-86) | NR | NR | I II III | RS | England |

| Hulscher et al[12] | 114 | 106 | 64/(35–78) | 69/(23–79) | 97/17 | 92/14 | I II | RCT | Netherlands |

| Omloo et al[14] | |||||||||

| Nakamura et al[13] | 71 | 84 | 64/(28-90) | 64/(28-90) | NR | NR | I II III | RS | Japan |

| Sasako et al[15] | 85 | 82 | 63/(38–75) | 60/(36–75) | 63/22 | 71/11 | II III | RCT | Japan |

| Wayman et al[16] | 20 | 20 | 63/(59-70) | 71/(43-78) | 15/5 | 15/5 | I II III | PS | England |

| Zheng et al[17] | 284 | 47 | 60.7/0.57 | 56.4/1.6 | 204/80 | 31/16 | II | RS | China |

| Ref. | Randomization | Blinding | Concealed allocation | Baseline features | Eligibility criteria | Loss tofollow-up | Selecting bias | Study quality |

| Hulscher et al[12] | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Fair |

| Omloo et al[14] | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Fair |

| Sasako et al[15] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Fair |

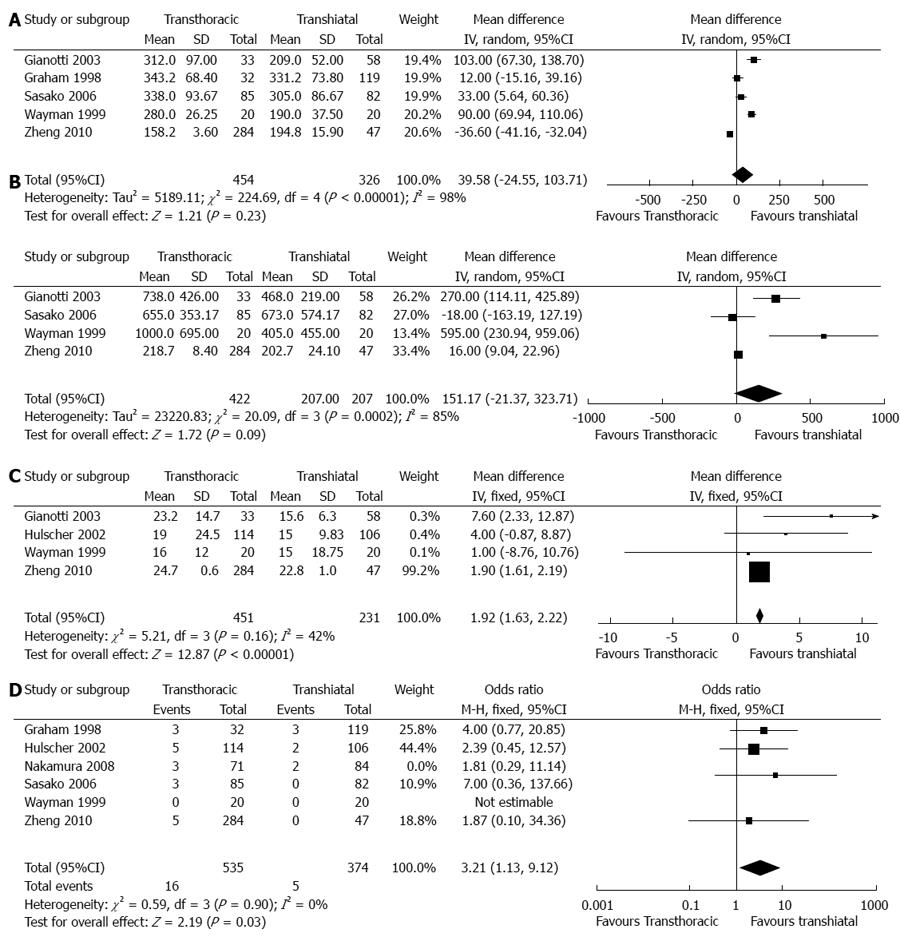

Duration of surgical time (min): In total, five articles provided the available data on the duration of surgical time[10,11,15-17]. Of these articles, two articles provided estimated standard deviations[15,16], and three articles reported significantly longer durations of surgery in the TT group than in the TH group. However, analysis of the pooled data showed no significance between the two groups (WMD = 39.58, 95%CI: -24.55-103.71, P = 0.23) (Figure 2).

Blood loss (mL): In total, five articles reported the available data on blood loss[10,12,15-17]. Of these, two articles estimated a standard deviation[15,16], and one article was not pooled with a sole mean[12]. Three articles reported a significant increase in blood loss in the TT group compared with the TH group. Furthermore, analysis of the pooled data showed no significance between the two groups (WMD = 151.17, 95%CI: -21.37-323.71, P = 0.09).

Hospital stay time (d): In total, four articles reported the available data on hospital stay time[10,12,16,17]. Of these articles, standard deviations were estimated in two articles[12,16], and one article was not pooled with a sole mean[11]. Two articles reported a significantly longer hospital stay time in the TT group than in the TH group. Furthermore, analysis of the pooled data also showed a significantly longer hospital stay time in the TT group than in the TH group (WMD = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.63-2.22, P < 0.00001).

30-d hospital mortality: In total, six articles reported the available data on 30-d hospital mortality[11-13,15-17]. All pooled articles showed no significance between the two groups. However, an analysis of pooled data showed a higher 30-d hospital mortality in the TT group than in the TH group (OR = 3.21, 95%CI: 1.13- 9.12, P = 0.03).

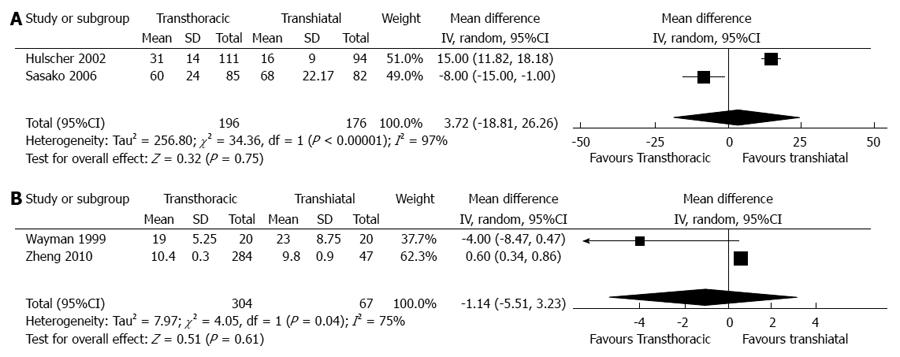

In total, four articles, including two RCTs and two non-RCTs, reported the available data on dissected lymph nodes[12,15-17]. Pooled outcomes in the RCTs showed no significant differences between the two groups (WMD = 3.72, 95%CI: -18.81-26.26, P = 0.75). Additionally, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in the non-RCTs (WMD = -1.14, 95%CI: -5.51-3.23, P = 0.61) (Figure 3).

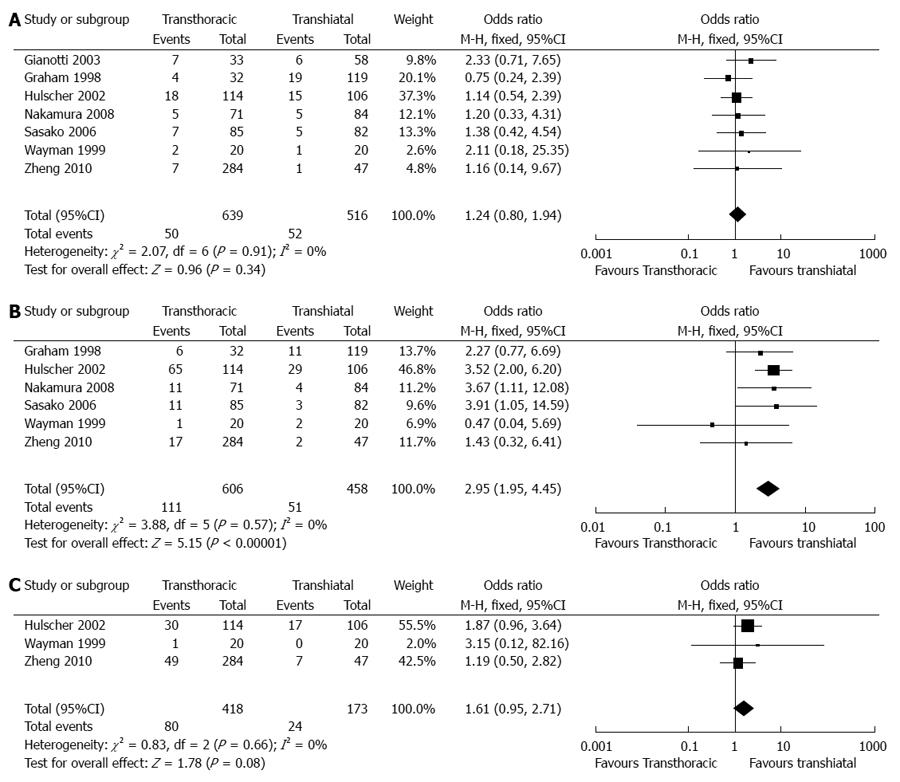

Anastomotic leaks: In total, seven articles reported the available data on anastomotic leaks[10-13,15-17]. Six articles reported no significant differences between the two groups, in accordance with the pooled outcomes (OR = 1.24, 95%CI: 0.80 -1.94, P = 0.34) (Figure 4).

Pulmonary complications: In total, six articles reported the available data on pulmonary complications[11-13,15-17]. Two articles reported a significantly higher incidence of pulmonary complications in the TT group than in the TH group. Furthermore, an analysis of the pooled data also provided evidence for this difference (OR = 2.95, 95%CI: 1.95-4.45, P < 0.00001).

Cardiovascular complications: In total, three articles reported the available data on cardiovascular complications[12,16,17]. All articles reported no significant difference between the two groups, in accordance with the pooled outcomes (OR = 1.61, 95%CI: 0.95-2.71, P = 0.08).

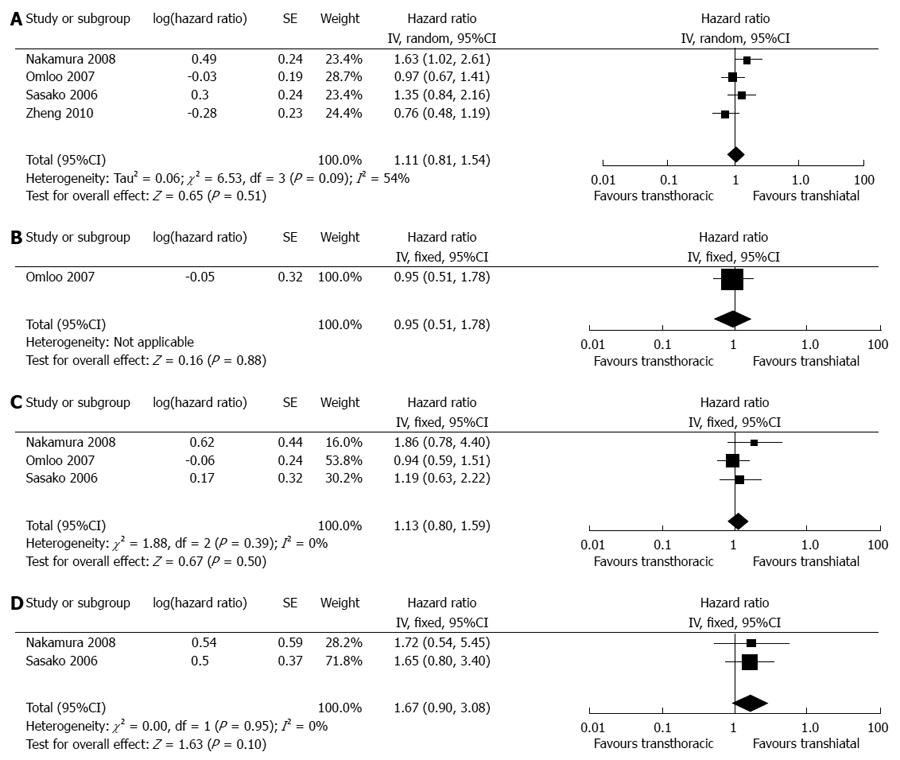

In total, seven articles reported the available data on the overall survival rate[9-13,15]. All pooled data did not show any significant differences in either all Siewert’s or single Siewert’s types (Figure 5). However, our estimated results demonstrated a potential trend of increased 5-year survival in the TH group compared with the TT group for both type III tumors. It is worth mentioning that one study reported significantly higher overall survival rates in the TH group than in the TT group[13] (P = 0.0053). The TH group had significantly better survival than the TT group for type II tumors (P = 0.0139). Another RCT reported no 5-year survival benefit for TT compared with TH for either type II or type III tumors, which led to its being closed[15]. Detailed survival information is given in Table 3.

| 1Ref. | 5-yr survival | Conclusions on overall survival | |

| TT | TH | ||

| Gianotti et al[10] | 37% | 42%1 | Overall 1-yr survival and 3-yr survival rates are 82% and 54% in the TT group and 86% and 60% in the TH group, respectively. The TT approach results in a better postoperative outcome without compromising surgical radicality or patient survival |

| Graham et al[11] | 20% | 17%1 | The 1-yr, 2-yr, 3-yr and 5-yr survivals are not affected by the use of preoperative radiotherapy or surgical approach. The TT and TH approaches are not associated with any difference in survival |

| Nakamura et al[13] | NR | NR | Overall survival of the TT group is significantly lower than that of the TH group. The TH group shows significantly better survival than TT for type II tumors, but not for type III tumors |

| Hulscher et al[12] Omloo et al[14] | 36% | 34%1 | Overall 1-yr survival and 3-yr survival rates are 66% and 43% in the TT group and 73% and 41% in the TH group, respectively. There is no significant overall survival benefit for either approach. For type I tumors, the TT approach shows a potential survival benefit over the TH approach (51% vs 37%, P = 0.33) |

| Sasako et al[15] | 37.9% | 52.3%1 | TH tends to achieve higher 5-yr survival rates for both type II and type III tumors compared with TT (52.2% vs 41.5% and 52.4% vs 34.9%). The trial was closed because TT does not improve survival after TH and led to increased morbidity |

| Zheng et al[17] | 34.9% | 40.19%1 | Overall 1-yr survival and 3-yr survival rates are 71% and 43.2% in the TT group and 71.8% and 46.3% in the TH group, respectively. No significant difference is found between groups |

At present, cancer of the esophagogastric junction has attracted worldwide attention due to its increasing prevalence in North America and Europe. Since Siewert et al classified three types of this tumor based on the anatomic location of the tumor center, the Siewert’s types have generally laid the foundation for treatment and prognosis of these tumors. Surgical resection is the ideal therapy for cancers of the esophagogastric junction. The main two surgical approaches are transthoracic and transhiatal resections. Transthoracic resection has given rise to several other approaches, including the left thoracic, right thoracic and even thoracoabdominal approaches, and different medical centers favor an individual transthoracic approach. Despite the potential for a wider resection of tumor margins and thoracic lymphadenectomy, pulmonary complications have been continuously reported after transthoracic resections. Transhiatal resection was first described by Grey Turner in 1933[18], and this approach often achieves lower short-term morbidity and mortality without formal thoracic lymphadenectomy. Until now, the proper approach for surgical treatment of cancers of the esophagogastric junction was still up for debate[19]. To clarify some of these issues, we undertook the present meta-analysis, concentrating on the objective analysis of the two approaches that are used to treat cancer of the esophagogastric junction.

Considering postoperative complications, pulmonary complications, such as pneumonia, atelectasis, acute respiratory distress syndrome and pulmonary embolism, are the most prominent and often account for the majority of postoperative deaths[20]. Our results showed a significantly higher incidence of pulmonary complications in the TT group, although Chou et al[21] reported no difference between the two groups in 2005. One potential rationale for explaining this is that thoracic surgery or combined upper abdominal resection carries a higher risk of postoperative pulmonary complications[22]. Nevertheless, early extubation and aggressive pulmonary rehabilitation[23] may reduce the rate of pulmonary complications. Anastomotic leakage, the main cause of mortality[24], was not significantly different between the groups. Previous studies have reported various outcomes in terms of anastomotic leakage[5,21,25]. This wide variation can be attributed to different manual anastomoses, surgical anastomosis sites and levels of expertise[24,26]. Cardiovascular complications were also pooled with no significant difference between the groups, consistent with that reported in a recent study comparing the two resection approaches[27]. In terms of 30-d hospital mortality, which was defined as hospital deaths related to special disease within 30 d after operation, our results found significantly lower 30-d hospital mortality rates, along with shorter hospital stays in the TH group than in the TT group. Existing evidences have confirmed that prolonged hospital stays are associated with anastomotic leakages[28]. Graham et al[11] reported no significance in postoperative complications and hospital deaths, however, which may have resulted from the small number of nonrandomized patients included in their study.

Lymph node clearance is regarded as a predominant prognostic factor for cancer of the esophagogastric junction. The removal of lymph nodes in the mediastinum is the primary goal of surgery. However, the optimum extent of lymph node resection is still controversial[29]. In the present study, we reported no significant difference between the groups with regard to lymph node resections, although previous studies reported less lymph node dissection in the transhiatal procedure than in the transthoracic procedure. This result may have been caused by surgeons’s indirect vision in the operation[21]. As the included articles reported, the transthoracic and transhiatal approaches led to a similar rate of lymphadenectomies in the abdominal cavity. However, transthoracic resections require a thorough mediastinal nodal dissection with an esophagectomy of sufficient length; therefore, transhiatal esophagogastrostomy is sometimes performed in the neck or thorax without cervical lymphadenectomy, leading to insufficient lymphadenectomy in the thoracic cavity.

We found no statistical significance regarding the long-term survival of the two surgical groups in the pooled studies. This outcome is supported by previously published literature[5,30]. However, a recent review predicted a superior 5-year survival for transhiatal resections, which is consistent with that in two included articles that reported potential higher overall survival rates in the TH group compared with the TT group in type II tumors[13,15]. For type III tumors, one of the two studies showed potential 5-year survival benefits in the TH group[15]. Meanwhile, the other study presented an obvious 14% 5-year survival rate benefit in the transthoracic approach compared to the transhiatal approach for type I tumors[13]. Therefore, some researchers recommend the transthoracic approach as the preferred option for type I tumors and the transhiatal approach for type II and III tumors. Furthermore, it should be mentioned that in 2002, Mariette et al[19] reported overall 3- and 5-year survival rates of 40.9% and 25.1%, respectively, which were not affected by the choice of surgical approach. The difference in survival rates was associated with R0 resection, pathologic node-positive category, and tumor differentiation. In 2005, Jensen et al[31] underlined patient age as a risk factor for long-term survival. Thus, the long-term survival of patients with cancers of the esophagogastric junction may also be influenced by tumor stage, complications, and R0 resections.

There are limitations to this meta-analysis when considering the differing qualities within the literature: (1) randomized controlled trials, prospective studies and retrospective studies were assessed using different standards and then pooled together, which may decrease the power of the outcomes; (2) we were unable to perform a subgroup analysis for each outcome concerning the Siewert’s types due to the lack of reported detailed data; (3) some indirect data acquisition methods were used, such as when dealing with the standard deviation from range; and (4) although the methodological application for pooling overall survival rates has been described in previous literature, we also keep our conservative position on the appropriate use in dealing with overall survival rate analysis.

This meta-analysis found no significance between the transthoracic and transhiatal approaches to cancers of the esophagogastric junction with regards to the duration of surgical time, blood loss, dissected lymph nodes, anastomotic leakage, or cardiovascular complications. However, we did observe shorter hospital stays, lower 30-d hospital mortality rates and decreased pulmonary complications in the transhiatal approach. For overall survival, although no significance was found in either all Siewert’s types or single Siewert’s type, a potential survival benefit was achieved for type III tumors using the transhiatal approach compared with the transthoracic approach. Therefore, we conclude that the transhiatal approach for cancers of the esophagogastric junction, especially for Siewert’s type III tumors, should be recommended as the optimal choice. The long-term outcome benefits of this decision should be evaluated in the future.

We thank Yi-Fei Li and Sen-Lin Yin for their help with the data analysis.

Cancer of the esophagogastric junction has attracted worldwide attention due to its increasing prevalence in North America and Europe. Since Siewert et al classified three types of this tumor based on the anatomic location of the tumor center, the Siewert’s type has generally laid the foundation for treatment and prognosis of this tumor. Surgical resection is the best therapeutic option for cancers of the esophagogastric junction.

The two main surgical approaches for cancers of the esophagogastric junction are transthoracic and transhiatal resections. Transthoracic resection achieves a wider resection of the tumor margins and thoracic lymphadenectomy. However, pulmonary complications are continuously reported after transthoracic resections. Transhiatal resection often obtains lower short-term morbidity and mortality, but this approach lacks a formal thoracic lymphadenectomy. Currently, the proper approach to surgical treatment of cancers of the esophagogastric junction remains under debate. To clarify some of these issues, authors undertook the present meta-analysis, concentrating on these two approaches to cancers of the esophagogastric junction.

Authors conducted this meta-analysis to address the issue described above. The results indicated shorter hospital stays, lower 30-d hospital mortality, and decreased pulmonary complications in the transhiatal group compared with the transthoracic group. Moreover, a potential survival benefit was achieved for type III tumors for the transhiatal approach.

The transhiatal approach for cancers of the esophagogastric junction, especially for Siewert’s types III, should be recommended as the optimal choice, and its long-term outcome benefits should be evaluated in the future.

In this meta-analysis, Wei et al investigated the outcomes of transthoracic vs transhiatal resection approaches for GE junction cancer. From a methodological point of view, the paper appears sound. Adequate measures seem to be taken in order to draw the conclusions from this meta-analysis.

P- Reviewer: Reim D, Zhou PH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Vial M, Grande L, Pera M. Epidemiology of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, gastric cardia, and upper gastric third. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;182:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allum WH, Stenning SP, Bancewicz J, Clark PI, Langley RE. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5062-5067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 752] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Colvin H, Dunning J, Khan OA. Transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy for distal esophageal cancer: which is superior? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hulscher JB, Tijssen JG, Obertop H, van Lanschot JJ. Transthoracic versus transhiatal resection for carcinoma of the esophagus: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rindani R, Martin CJ, Cox MR. Transhiatal versus Ivor-Lewis oesophagectomy: is there a difference? Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:187-194. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yang K, Chen HN, Chen XZ, Lu QC, Pan L, Liu J, Dai B, Zhang B, Chen ZX, Chen JP. Transthoracic resection versus non-transthoracic resection for gastroesophageal junction cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stein HJ, Feith M, Siewert JR. Cancer of the esophagogastric junction. Surg Oncol. 2000;9:35-41. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med. 1998;17:2815-2834. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4895] [Cited by in RCA: 6875] [Article Influence: 343.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gianotti L, Braga M, Landoni L, Mari G, Scaltrini F, Di Castelnuovo A, Di Carlo V. Outcome of patients with cancer of the esophagogastric junction in relation to histology and surgical strategy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1948-1952. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Graham AJ, Finley RJ, Clifton JC, Evans KG, Fradet G. Surgical management of adenocarcinoma of the cardia. Am J Surg. 1998;175:418-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hulscher JB, van Sandick JW, de Boer AG, Wijnhoven BP, Tijssen JG, Fockens P, Stalmeier PF, ten Kate FJ, van Dekken H, Obertop H. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1662-1669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1144] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nakamura T, Oguma H, Sasagawa T, Ota M, Kitamura Y, Yamamoto M. Left thoracoabdominal approach for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1332-1337. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Omloo JM, Lagarde SM, Hulscher JB, Reitsma JB, Fockens P, van Dekken H, Ten Kate FJ, Obertop H, Tilanus HW, van Lanschot JJ. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the mid/distal esophagus: five-year survival of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:992-1000; discussion 1000-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 514] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Sairenji M, Arai K, Kinoshita T, Nashimoto A, Hiratsuka M. Left thoracoabdominal approach versus abdominal-transhiatal approach for gastric cancer of the cardia or subcardia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:644-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 296] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wayman J, Dresner SM, Raimes SA, Griffin SM. Transhiatal approach to total gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. Br J Surg. 1999;86:536-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zheng B, Chen YB, Hu Y, Wang JY, Zhou ZW, Fu JH. Comparison of transthoracic and transabdominal surgical approaches for the treatment of adenocarcinoma of the cardia. Chin J Cancer. 2010;29:747-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schiesser M, Schneider PM. Surgical strategies for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;182:93-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mariette C, Castel B, Toursel H, Fabre S, Balon JM, Triboulet JP. Surgical management of and long-term survival after adenocarcinoma of the cardia. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1156-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Atkins BZ, Shah AS, Hutcheson KA, Mangum JH, Pappas TN, Harpole DH, D’Amico TA. Reducing hospital morbidity and mortality following esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1170-1176; discussion 1170-1176. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Chou SH, Kao EL, Chuang HY, Wang WM, Wu DC, Huang MF. Transthoracic or transhiatal resection for middle- and lower-third esophageal carcinoma? Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Smetana GW. Preoperative pulmonary evaluation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:937-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bartels H, Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Risk analysis in esophageal surgery. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;155:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sauvanet A, Mariette C, Thomas P, Lozac’h P, Segol P, Tiret E, Delpero JR, Collet D, Leborgne J, Pradère B. Mortality and morbidity after resection for adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction: predictive factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:253-262. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Carboni F, Lorusso R, Santoro R, Lepiane P, Mancini P, Sperduti I, Santoro E. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: the role of abdominal-transhiatal resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:304-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ott K, Bader FG, Lordick F, Feith M, Bartels H, Siewert JR. Surgical factors influence the outcome after Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy with intrathoracic anastomosis for adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: a consecutive series of 240 patients at an experienced center. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1017-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kawoosa NU, Dar AM, Sharma ML, Ahangar AG, Lone GN, Bhat MA, Singh S. Transthoracic versus transhiatal esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma: experience from a single tertiary care institution. World J Surg. 2011;35:1296-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | van Heijl M, van Wijngaarden AK, Lagarde SM, Busch OR, van Lanschot JJ, van Berge Henegouwen MI. Intrathoracic manifestations of cervical anastomotic leaks after transhiatal and transthoracic oesophagectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:726-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gronnier C, Piessen G, Mariette C. Diagnosis and treatment of non-metastatic esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: what are the current options? J Visc Surg. 2012;149:e23-e33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chou SH, Chuang HY, Huang MF, Lee CH, Yau HM. A prospective comparison of transthoracic and transhiatal resection for esophageal carcinoma in Asians. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:707-710. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Jensen LS, Pilegaard HK, Puho E, Pahle E, Melsen NC. Outcome after transthoracic resection of carcinoma of the oesophagus and oesophago-gastric junction. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:191-196. [PubMed] |