Published online Jul 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9556

Revised: April 2, 2014

Accepted: April 27, 2014

Published online: July 28, 2014

Processing time: 302 Days and 10.3 Hours

AIM: To describe our experience in treating rectal cancer by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), report morbidity and mortality and oncological outcome.

METHODS: A total of 425 patients with rectal cancer (120 T1, 185 T2, 120 T3 lesions) were staged by digital rectal examination, rectoscopy, transanal endosonography, magnetic resonance imaging and/or computed tomography. Patients with T1-N0 lesions and favourable histological features underwent TEM immediately. Patients with preoperative stage T2-T3-N0 underwent preoperative high-dose radiotherapy; from 1997 those aged less than 70 years and in good general health also underwent preoperative chemotherapy. Patients with T2-T3-N0 lesions were restaged 30 d after radiotherapy and were then operated on 40-50 d after neoadjuvant therapy. The instrumentation designed by Buess was used for all procedures.

RESULTS: There were neither perioperative mortality nor intraoperative complications. Conversion to other surgical procedures was never required. Major complications (urethral lesions, perianal or retroperitoneal phlegmon and rectovaginal fistula) occurred in six (1.4%) patients and minor complications (partial suture line dehiscence, stool incontinence and rectal haemorrhage) in 42 (9.9%). Postoperative pain was minimal. Definitive histological examination of the 425 malignant lesions showed 80 (18.8%) pT0, 153 (36%) pT1, 151 (35.5%) pT2, and 41 (9.6%) pT3 lesions. Eighteen (4.2%) patients (ten pT2 and eight pT3) had a local recurrence and 16 (3.8%) had distant metastasis. Cancer-specific survival rates at the end of follow-up were 100% for pT1 patients (253 mo), 93% for pT2 patients (255 mo) and 89% for pT3 patients (239 mo).

CONCLUSION: TEM is a safe and effective procedure to treat rectal cancer in selected patients without evidence of nodal involvement. T2-T3 lesions require preoperative neoadjuvant therapy.

Core tip: The gold standard treatment for locally advanced rectal cancer, major surgery, is associated with a high incidence of definitive stoma. In the 1980s, Buess pioneered the removal of rectal lesions with full-thickness excision by transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM). It was subsequently demonstrated that T1-N0 lesions can be treated by TEM alone. However, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy can downstage T2-T3-N0 lesions and even elicit a complete response. In our experience, the local recurrence and survival rates of selected patients with local-advanced rectal cancer and no nodal involvement treated with neoadjuvant therapy and TEM do not differ significantly from patients treated by major surgery.

- Citation: Guerrieri M, Gesuita R, Ghiselli R, Lezoche G, Budassi A, Baldarelli M. Treatment of rectal cancer by transanal endoscopic microsurgery: Experience with 425 patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(28): 9556-9563

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i28/9556.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9556

Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) is a safe and feasible minimally invasive surgical approach to treat benign adenoma and early-stage carcinoma of the rectum[1]. The standard treatment for more advanced rectal cancer remains major surgery with anterior or abdominoperineal resection and total mesorectal excision[1]. However, these procedures are associated with high rates of complications, including genitourinary and sexual dysfunction (30%-40%), anastomotic leak (5%-17%), and long-term functional bowel disturbance[2]. Perioperative mortality is usually 2%-3%, and overall morbidity is 20%-30%[3]. These considerations explain the interest in the development of locoregional approaches also for more advanced rectal disease. The demonstration that neoadjuvant treatment improves overall and disease-free survival (respectively OS and DFS) of patients with rectal cancer has raised hopes for treatment approaches involving less morbidity and mortality, and that ensure a better quality of life. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT) downstages 59% of locally advanced rectal tumours and induces a reduction > 50% in 22%[4]. Recent studies show that radiotherapy (RT) may induce complete pathological response in 10% to 30% of patients[2]. These favourable findings have enabled selected patients with T2-T3-N0 rectal cancer to be treated by local excision. We report our institution’s experience with TEM in terms of operative morbidity and mortality with emphasis on oncological outcome.

From February 1992 to February 2013, 425 patients with rectal cancer (120 stage T1, 185 stage T2, and 120 stage T3) underwent TEM at the Department of General Surgery of Università Politecnica delle Marche (Ancona, Italy). All were enrolled in this study.

T1-N0-M0 rectal lesions; T2-T3-N0-M0 rectal lesions [diameter < 3 cm, high-risk patients (ASA 3-4) and patients who refused conventional resection].

Written informed consent was obtained with regard to the oncological risks of local excision (local recurrence and distant metastasis) and to possible intra- and postoperative complications (bleeding, suture dehiscence, temporary gas or stool incontinence, conversion to laparotomy with colonic resection and colostomy, etc.). All patients agreed to undergo close follow-up.

All patients underwent clinical examination, which included digital rectal examination (DRE) to assess tumour fixation; routine laboratory testing, including CEA and CA 19-9 markers; colonoscopy with collection of large biopsies for histology and grading; rigid rectoscopy to measure tumour distance from the anal verge, evaluate its circumferential location in the wall and establish the appropriate decubitus position on the operating table; transanal endosonography (EUS); abdominal and pelvic computed tomography (CT) scanning with 3 mm slice thickness or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), bone scintigraphy and chest-X-rays. Before RT, the site of each negative biopsy was marked endoscopically with an Indian ink tattoo, so that it could to be identified even after reduction of the primary lesion.

Patients with T1-N0 lesions underwent TEM immediately; those who had T2-T3 lesions underwent RT in a 10-15 MV linear accelerator (daily dose 180 cGy, total dose 5040 cGy, 28 fractions over 5 wk). Anus, rectum, mesorectum and regional and iliac lymph nodes were irradiated. Since January 1997, patients < 70 years old having a good performance status received preoperative chemotherapy with continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil (200 mg/m2/d); from 2003 they received capecitabine (1650 mg/m2/d) during RT. Restaging was performed 30 d after RT completion by DRE, rectoscopy, transanal EUS, MRI or CT. If a lower T stage was documented by EUS, CT/MRI, and definitive histological examination the tumour was considered as being downstaged and TEM was performed 40-50 d after completion of neoadjuvant therapy.

Bowel preparation was performed the day before the operation with 4 L of an osmotic agent (Selg-Esse 1000, Promefarm, Milano, Italy); short-term antibiotic prophylaxis (cefuroxime 2 g + metronidazole 500 mg) was administered at the time of anaesthesia induction.

Our institution’s protocol envisages evaluation 1 mo after discharge by clinical examination, DRE and rectoscopy. Subsequent follow-up visits, which include clinical examination, rectoscopy with multiple biopsies, EUS, and MRI or CT, are scheduled at 3-mo intervals over the first 2 years, at 6-mo intervals until the 5th year, and annually thereafter.

The instrumentation was designed by Buess et al[5] and developed by Wolf (Tuttlingen, Germany) and was used for all procedures. It comprised a modified 12- or 20-cm long rectoscope with three-dimensional vision and three operative channels. The lesion was located preoperatively by rigid rectoscopy; the patient was placed in supine, lateral or prone decubitus so that the lesion lay in the inferior part of the operative field. The rectoscope was fixed to the operative field by a Martin’s arm. A working insert was connected with sealing elements to prevent gas loss. The rectum was inflated with CO2; endoluminal pressure was controlled by the endosurgical unit. Full-thickness excision was performed with a margin of at least 1 cm of normal mucosa. For posterior and lateral lesions, the largest possible amount of local perirectal fat was dissected and removed to reach the avascular plane of the mesorectal fascia or the prostate capsule/vaginal septum for anterior lesions. Real-time intraoperative histological margin assessment confirmed complete excision in doubtful cases. A running suture closed the rectal defect.

A stratified analysis was performed according to preoperative or pre-RT disease stage. There were 120 patients with T1 preoperative stage, 185 with T2 and 120 patients T3 pre-RT stage.

The main patient characteristics were summarized using absolute and per cent frequencies for categorical variables; median and 25th and 75th percentiles were used as a central and variability measure for quantitative variables.

Comparisons of post-RT disease stages were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance and results were shown by means of box-plots.

OS, cancer-specific survival (CSS), and event-free survival (EFS) were estimated using Kaplan-Maier curves. The log-rank test was applied to compare curves between strata; 95%CI were calculated for the estimated cumulative probabilities.

A level of probability equal to 5% was used to assess statistical significance. All analyses were performed using the R statistical package.

Patients with preoperative stage T1 (Table 1) were more frequently males (65.0%), had a median age of 68 years (25th-75th percentile: 60-74) and a median follow-up of 82 mo (25th-75th percentile: 48-144). The median operative time was 70 min (25th-75th percentile: 60-90), the median hospital stay was 2 d (25th-75th percentile: 2-3), and according to definitive histology, five lesions (4.2%) were stage pT2.

| Variables | |

| Preoperative stage T1 (120 patients) | |

| Sex, male | 79 (65.0) |

| Age (yr) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 68 (60-74) |

| Follow-up (mo) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 82 (48-144) |

| Operative time (min) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 70 (60-90) |

| Hospital stay (d) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 2 (2-3) |

| Definitive histology [n (%)] | |

| pT1 | 110 (91.7) |

| pT2 | 10 (8.3) |

| Stage T2 before radiotherapy (185 patients) | |

| Sex, male | 120 (64.9) |

| Age (yr) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 68 (60-74) |

| Follow-up (mo) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 53 (32-125) |

| Operative time (min) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 70 (60-120) |

| Hospital stay (d) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 4 (3-5) |

| Post-radiotherapy stage | |

| pT0 | 63 (34.1) |

| pT1 | 25 (13.5) |

| pT2 | 97 (52.4) |

| Stage T3 before radiotherapy (120 patients) | |

| Sex, male | 70 (58.3) |

| Age (yr) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 69.5 (62.5-75) |

| Follow-up (mo) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 70 (42-133.5) |

| Operative time (min) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 90 (60-120) |

| Hospital stay (d) | |

| [median, (25th p-75th p)] | 3 (3-4) |

| Postradiotherapy stage | |

| pT0 | 17 (14.2) |

| pT1 | 13 (10.8) |

| pT2 | 49 (40.8) |

| pT3 | 41 (34.2) |

Patients with T2 stage before RT (Table l) were more frequently males (64.9%) and had a median age of 68 years (25th-75th percentile: 60-72). The median follow-up was 53 mo (25th-75th percentile: 32-125), the median operative time was 70 min (25th-75th percentile: 60-120) and the median hospital stay was 4 d (25th-75th percentile: 3-5). After RT, 63 (34.1%) lesions were stage pT0, 25 (13.5%) were stage pT1 and 97 (52.4%) were stage pT2.

Patients with stage T3 before RT (Table 1) were more frequently males (58.3%) and had a median age of 69.5 years (25th-75th percentile: 62.5-75). The median follow-up was 70 mo (25th-75th percentile: 42-133.5), the median operative time was 90 min (25th-75th percentile: 60-120), and the median hospital stay was 3 d (25th-75th percentile: 3-4). After RT, 17 (14.2%) lesions were stage pT0, 13 (10.8%) were stage pT1, 49 (40.8%) were stage pT2, and 41 (34.2%) were stage pT3.

The main characteristics of patients with T2 and T3 lesions before RT are reported in Table 1, respectively.

Side effects of RT were cutaneous erythema in 69% and diarrhoea in 26% of patients.

Neither perioperative mortality nor intraoperative complications were observed. Conversion to other surgical procedures was never required. Postoperative pain was minimal and analgesics (a single dose of Lixidol 30 mg, Roche, Milano, Italy) were required over the first 48 h by 39 (9%) patients. Patients were allowed to drink on the 1st postoperative day and to eat the next day. All were walking freely within 12 h of the operation. Minor complications, i.e., partial suture line dehiscence, stool incontinence and rectal haemorrhage, occurred in 42 patients (9.9%). Partial suture line dehiscence was managed by antibiotic therapy; stool incontinence resolved within 2 mo of the operation after treatment by physiotherapy and anal sphincter biofeedback, and haemorrhage was addressed with blood transfusions.

Major complications occurred in six patients (1.4%). There were two urethral lesions, a perianal and two retroperitoneal phlegmons, and a rectovaginal fistula. One urethral lesion occurred in a male patient during wide anterior dissection of the prostate capsule; the lesion was sutured during the TEM procedure and the patient was discharged with a urinary catheter that was removed 3 wk later without further problems. The other urethral lesion involved an elderly male patient who refused other procedures and is still alive with a urinary catheter. The perianal phlegmon required drainage and temporary laparoscopic ileostomy. One retroperitoneal phlegmon required surgical drainage and colostomy; the other was treated by surgical drainage and temporary ileostomy that was closed after 6 mo. Finally, the rectovaginal fistula was treated by laparoscopic ileostomy and a new suture by TEM, the ileostomy was then closed. The patient is alive and has experienced no further complications.

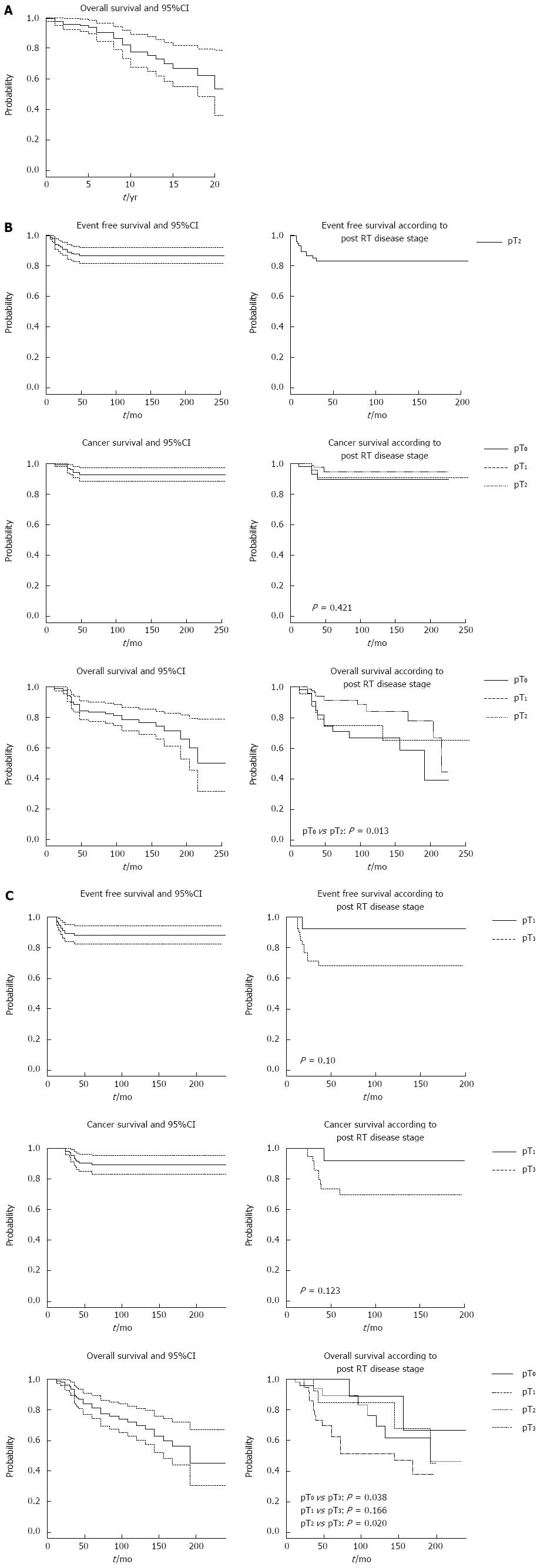

Figure 1 shows the cumulative probabilities of failure and 95%CI at the end of follow-up, as estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis for the three strata.

Twenty-two subjects with T1 stage preoperatively died from other causes, with a probability of death at the end of follow-up (253 mo) equal to 47% (95%CI: 21%-64%); no local recurrences, metastases or cancer-specific deaths occurred in this stratum.

Patients with pre-RT stage T2 (Table 2) had a 13% probability of developing local recurrence or metastasis (95%CI: 8-18). The cumulative probability of cancer-specific death was 7% (95%CI: 3-12). Thirty-three patients died, with a cumulative probability at the end of follow-up (255 mo) of 50% (95%CI: 21-68).

| Cumulative probability | Value |

| Preoperative stage T1 (120 patients) | |

| Follow-up: 253 mo | Patients with stage T1 before radiotherapy |

| Probability of death (95%CI) | 0.47 (0.21-0.64) |

| Events (n) | 22 |

| Stage T2 before radiotherapy (185 patients) | |

| Follow-up: 255 mo | Patients with stage T2 lesions before radiotherapy |

| Probability of local recurrence or | 0.13 (0.08-0.18) |

| metastasis (95%CI) | |

| Events (n) | 21 |

| Probability of cancer-specific death (95%CI) | 0.07 (0.03-0.12) |

| Events (n) | 10 |

| Probability of death (95%CI) | 0.50 (0.21-0.68) |

| Events (n) | 33 |

| Stage T3 before radiotherapy (120 patients) | |

| Follow-up: 239 mo | Patients with stage T3 lesions before radiotherapy |

| Probability of local recurrence or | 0.12 (0.05-0.17) |

| metastasis (95%CI) | |

| Events (n) | 13 |

| Probability of cancer-specific death (95%CI) | 0.11 (0.06-0.17) |

| Events (n) | 11 |

| Probability of death (95%CI) | 0.55 (0.33-0.70) |

| Events (n) | 33 |

Patients with pre-RT stage T3 (Table 2) developed local recurrence or metastasis (n = 13) or died from cancer (n = 11) with cumulative probabilities of 12% (95%CI: 5-17) and 11% (95%CI: 6-17), respectively. The probability of death at the end of follow-up (239 mo) was 50% (95%CI: 33-70).

The Kaplan-Meier curves of EFS, CSS, and OS probabilities are shown in Figure 1, with T2 and T3 patients subdivided by post-RT stage.

TEM has been devised to remove adenomas localized in the middle and upper rectum[6].

Local cancer resection has been performed for many years in selected elderly, high-risk patients, and in those who refused permanent colostomy, as well as for palliative therapy[7-12]. Although the gold standard approaches, i.e., anterior and abdominoperineal resection, have provided excellent results in terms of local recurrence and survival rates, they are dearly paid for by a high incidence of complications and impaired quality of life (anorectal, sexual and urinary dysfunction). On the other hand some conventional sphincter-preserving techniques, such as transanal resection with a Parks retractor, are associated with an unacceptably high rate of recurrence (up to 29%). Unlike conventional transanal excision with an anal retractor, TEM offers an exceptionally good view of the whole rectum and enables precise removal of lesions located not only in the lower and middle rectum, but also in the upper rectal area. It also affords highly precise dissection and full-thickness excision with a suitable margin (ablation with 1 cm of free margin and with the largest possible amount of adjacent perirectal fat).

Over time the TEM indications have been extended to include selected patients with early rectal cancer.

Local excision is considered as a curative approach for primary tumours limited to the mucosa or invading the submucosa without high-risk features (poor differentiation, vascular and neural invasion, mucinous histology and ulceration), as also reported in the guidelines for colon and rectal cancer treatment (Clinical Guideline Colorectal Cancer: The diagnosis and the management of colorectal cancer; November 2011).

The first prospective randomized trial comparing treatment of T1-N0 rectal cancer by TEM vs anterior resection was published in 1996; it described non-significant differences in local recurrence (4.2%) and five-year survival (96%). The rate of local recurrence after local resection of pT1 lesions using TEM is 4%-6% and is not significantly different from the rates reported for conventional surgery[13].

None of our 120 T1 patients had a recurrence or distant metastasis or died from the tumour.

Our study demonstrated that TEM provides comparable results to open surgery in terms of survival, but being a minimally invasive procedure, it also offers superior outcomes under most other respects.

An extension of the indications to include more advanced lesions is a matter of debate; however, advances in neoadjuvant RT techniques and chemotherapy have enabled exploration of multimodal treatment strategies to improve local control rates.

Preoperative CRT reduces local recurrence rates and improves OS compared with surgery alone, and it is more effective than postoperative RT[1,2,4,7,9,14-22]. It has the potential to induce tumour downstaging, thus enabling less radical surgery, sphincter preservation, eradication of any micrometastatic disease (locoregional and distant) early in the treatment course, and a reduction in complication rates, thereby enhancing quality of life. Preoperative RT also offers biological (decreased tumour seeding at the time of surgery and increased radiosensitivity because of greater cell oxygenation) and functional advantages (possibility of converting coloanal resection to local excision). An additional benefit in patients with locally advanced unresectable disease is an increased resectability rate. Preoperative chemoradiation does not add to the overall surgical complication rate, including wound infection and anastomotic leaks. Local excision is associated with low mortality and a very low rate of complications compared with major resection.

However, successful TEM performance rests on the key factors of patient selection, preoperative staging of the primary rectal tumour, and assessment of node involvement. Even though EUS and MRI have similar sensitivities (67% vs 66%) and specificities (78% vs 76%) in detecting nodal disease, both are highly operator-dependent. MRI provides excellent imaging of th rectum, mesorectum, fascia propria of the rectum, and other pelvic structures.

The role of TEM in managing T2-T3 lesions remains controversial, and the technique is mainly applied to treat older patients with co-morbidities or to perform palliative surgery. The results of 100 TEM resections of small T2-T3-N0-M0 distal rectal lesions subjected to preoperative high-dose RT at our institution were published in 2005. The probability of local recurrence at 10-year follow-up was 5%; the probability of metastasis was 2%; CSS was 89% and OS was 72%. These rates are not significantly different from those obtained with radical or laparoscopic surgery at our institution[10,16].

In our 185 selected patients with T2 rectal lesions, preoperative CRT and TEM involved a probability of local recurrence and metastasis of 13% (95%CI: 8-18). DFS in pT2 patients at the end of follow-up was 93% (95%CI: 88-97).

Neither local recurrence nor distant metastasis arose in patients whose tumour had been downstaged or in those where the tumour mass had been greatly reduced (≥ 50%). We thus agree with previous reports that response to CRT is the strongest predictor of successful local excision[2,4,22-24].

The role of TEM in patients with T3 lesion has been less frequently explored, and radical surgery remains the gold standard treatment for these lesions. Local excision is restricted to patients with high co-morbidities, advanced age, high ASA grade and to those who refuse conventional resection. In a previous study of neoadjuvant therapy and TEM in a selected group of 120 patients with T3 lesions before RT[25], we reported a probability of local recurrence and metastasis of 12% (95%CI: 5-17), and a DFS at the end of follow-up of 89% (95%CI: 83-94): these rates are similar to those of open or laparoscopic surgery.

In conclusion, TEM can be considered as a first-line treatment for rectal adenoma and T1 rectal cancer. In T2-T3 rectal cancer, patient selection and preoperative CRT are mandatory to achieve results comparable to those of major surgery. Randomized studies are needed to gain further insights into the possibility of extending the indications for TEM.

Rectal cancer has a high incidence that increases with age and requires a multidisciplinary approach (radiologist, gastroenterologist, surgeon, oncologist and radiotherapist) to reduce the cancer mortality rate. Traditional surgery provides excellent results in terms of local recurrence and distant metastasis, but carries a high rate of mortality and postoperative complications, in addition to severely affecting quality of life.

Early diagnosis (by faecal occult blood test, colonoscopy, and digital rectal examination) and promotion of minimally invasive surgical approaches are the current challenges for this disease.

In the 1980s, Buess developed a new surgical tool based on a modified rectoscope with a magnified operative field that allows the removal rectal lesions by full-thickness excision. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy can frequently downstage rectal lesions and even induce a complete response.

In their experience, selected patients with rectal cancer and no nodal involvements can benefit from transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) local excision (T1N0 lesions immediately, T2-T3-N0 after neoadjuvant therapy), experiencing a low rate of postoperative complications and a limited impact on quality of life. The oncological results are similar to those of traditional surgery.

The authors present their experience with 425 patients who underwent TEM. This is a retrospective study, but the TEM sample is large and valuable as a reference. The results are exciting.

P- Reviewer: Cesar D, Meshikhes AWN, Seow-Choen F, Triantafyllou K, Tong WD, Tajika M S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Palma P, Horisberger K, Joos A, Rothenhoefer S, Willeke F, Post S. Local excision of early rectal cancer: is transanal endoscopic microsurgery an alternative to radical surgery? Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:172-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Allaix ME, Arezzo A, Giraudo G, Morino M. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery vs. laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for T2N0 rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:2280-2287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Blair S, Ellenhorn JD. Transanal excision for low rectal cancers is curative in early-stage disease with favorable histology. Am Surg. 2000;66:817-820. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lezoche E, Guerrieri M, Paganini AM, Baldarelli M, De Sanctis A, Lezoche G. Long-term results in patients with T2-3 N0 distal rectal cancer undergoing radiotherapy before transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1546-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Buess G, Mentges B. Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (T.E.M.). Minimally Invasive Therapy. 1992;1:101-109. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cocilovo C, Smith LE, Stahl T, Douglas J. Transanal endoscopic excision of rectal adenomas. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1461-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Kiss DR, Rawet V, Scanavini A, Santinho PM, Nadalin W. Preoperative chemoradiation therapy for low rectal cancer. Impact on downstaging and sphincter-saving operations. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1703-1707. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Heintz A, Mörschel M, Junginger T. Comparison of results after transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical resection for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1145-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim CJ, Yeatman TJ, Coppola D, Trotti A, Williams B, Barthel JS, Dinwoodie W, Karl RC, Marcet J. Local excision of T2 and T3 rectal cancers after downstaging chemoradiation. Ann Surg. 2001;234:352-38; discussion 352-38;. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sengupta S, Tjandra JJ. Local excision of rectal cancer: what is the evidence? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1345-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stipa F, Burza A, Lucandri G, Ferri M, Pigazzi A, Ziparo V, Casula G, Stipa S. Outcomes for early rectal cancer managed with transanal endoscopic microsurgery: a 5-year follow-up study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:541-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Varma MG, Rogers SJ, Schrock TR, Welton ML. Local excision of rectal carcinoma. Arch Surg. 1999;134:863-87; discussion 863-87;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Winde G, Nottberg H, Keller R, Schmid KW, Bünte H. Surgical cure for early rectal carcinomas (T1). Transanal endoscopic microsurgery vs. anterior resection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:969-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Balch GC, De Meo A, Guillem JG. Modern management of rectal cancer: a 2006 update. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3186-3195. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bozzetti F, Baratti D, Andreola S, Zucali R, Schiavo M, Spinelli P, Gronchi A, Bertario L, Mariani L, Gennari L. Preoperative radiation therapy for patients with T2-T3 carcinoma of the middle-to-lower rectum. Cancer. 1999;86:398-404. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lee W, Lee D, Choi S, Chun H. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery and radical surgery for T1 and T2 rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1283-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martling AL, Holm T, Rutqvist LE, Moran BJ, Heald RJ, Cedemark B. Effect of a surgical training programme on outcome of rectal cancer in the County of Stockholm. Stockholm Colorectal Cancer Study Group, Basingstoke Bowel Cancer Research Project. Lancet. 2000;356:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 591] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nastro P, Beral D, Hartley J, Monson JR. Local excision of rectal cancer: review of literature. Dig Surg. 2005;22:6-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ruo L, Guillem JG, Minsky BD, Quan SH, Paty PB, Cohen AM. Preoperative radiation with or without chemotherapy and full-thickness transanal excision for selected T2 and T3 distal rectal cancers. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2002;17:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vecchio FM, Valentini V, Minsky BD, Padula GD, Venkatraman ES, Balducci M, Miccichè F, Ricci R, Morganti AG, Gambacorta MA. The relationship of pathologic tumor regression grade (TRG) and outcomes after preoperative therapy in rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:752-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lezoche E, Baldarelli M, Lezoche G, Paganini AM, Gesuita R, Guerrieri M. Randomized clinical trial of endoluminal locoregional resection versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for T2 rectal cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1211-1218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bujko K, Richter P, Smith FM, Polkowski W, Szczepkowski M, Rutkowski A, Dziki A, Pietrzak L, Kołodziejczyk M, Kuśnierz J. Preoperative radiotherapy and local excision of rectal cancer with immediate radical re-operation for poor responders: a prospective multicentre study. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106:198-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lezoche E, Guerrieri M, Paganini AM, D’Ambrosio G, Baldarelli M, Lezoche G, Feliciotti F, De Sanctis A. Transanal endoscopic versus total mesorectal laparoscopic resections of T2-N0 low rectal cancers after neoadjuvant treatment: a prospective randomized trial with a 3-years minimum follow-up period. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:751-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rödel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, Füzesi L, Klimpfinger M, Fietkau R, Liersch T, Hohenberger W, Raab R, Sauer R. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8688-8696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 918] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 47.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Maslekar S, Pillinger SH, Monson JR. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for carcinoma of the rectum. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:97-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |