Published online Jul 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8709

Revised: February 5, 2014

Accepted: March 19, 2014

Published online: July 14, 2014

Processing time: 248 Days and 23.1 Hours

AIM: To determine the dose-related effects of a novel probiotic combination, I.31, on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-related quality of life (IBS-QoL).

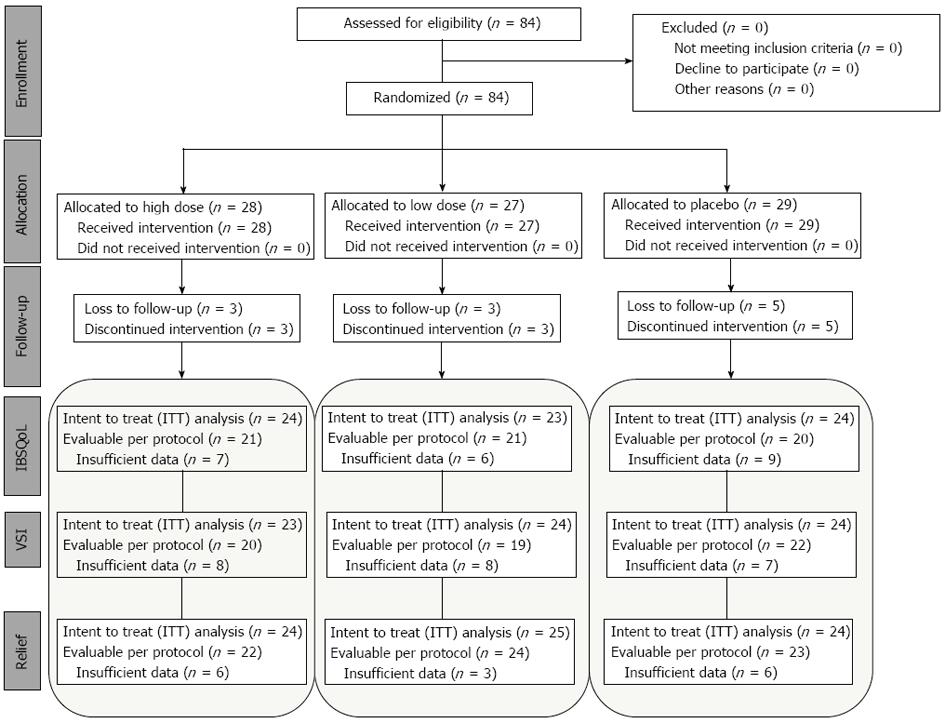

METHODS: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled intervention clinical trial with three parallel arms was designed. A total of 84 patients (53 female, 31 male; age range 20-70 years) with IBS and diarrhea according to Rome-III criteria were randomly allocated to receive one capsule a day for 6 wk containing: (1) I.31 high dose (n = 28); (2) I.31 low dose (n = 27); and (3) placebo (n = 29). At baseline, and 3 and 6 wk of treatment, patients filled the IBSQoL, Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI), and global symptom relief questionnaires.

RESULTS: During treatment, IBS-QoL increased in all groups, but this increment was significantly larger in patients treated with I.31 than in those receiving placebo (P = 0.008). After 6 wk of treatment, IBS-QoL increased by 18 ± 3 and 22 ± 4 points in the high and the low dose groups, respectively (P = 0.041 and P = 0.023 vs placebo), but only 9 ± 3 in the placebo group. Gut-specific anxiety, as measured with VSI, also showed a significantly greater improvement after 6 wk of treatment in patients treated with probiotics (by 10 ± 2 and 14 ± 2 points, high and low dose respectively, P < 0.05 for both vs 7 ± 1 score increment in placebo). Symptom relief showed no significant changes between groups. No adverse drug reactions were reported following the consumption of probiotic or placebo capsules.

CONCLUSION: A new combination of three different probiotic bacteria was superior to placebo in improving IBS-related quality of life in patients with IBS and diarrhea.

Core tip: Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a benign functional gut disorder, and its severity is closely related to the impact of the disorder on quality of life. Probiotic bacteria have been shown to have a modest beneficial effect on abdominal symptoms in patients with IBS, but the effect of probiotics on IBS-related quality of life (IBS-QoL) is unclear. The present study was designed to specifically address the effect of a probiotic combination (I.31) on IBS-QoL, and demonstrates that I.31 is superior to placebo in improving IBS-QoL. These data suggest that I.31 may be beneficial for the global management of this complex disorder.

- Citation: Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Llop E, Suárez C, Álvarez B, Abreu L, Espadaler J, Serra J. I.31, a new combination of probiotics, improves irritable bowel syndrome-related quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(26): 8709-8716

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i26/8709.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8709

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic functional gut disorder that affects about 8%-10% of the population in Western countries, mainly young and middle-aged women[1]. Although IBS, as with other functional gut disorders, is a benign disorder with a good long-term prognosis, it has an important impact on a patient’s quality of life[2,3]. IBS also produces a significant economic burden due to both direct health care-related costs and indirect costs due to impaired work productivity[4]. In fact, IBS has been proposed as the second leading cause of absenteeism after the common cold[5]. The severity of IBS ranges from mild, sporadic symptoms, to severe, invalidating symptoms. It has been shown that severity is closely related to the impact of the disease on a patient’s quality of life[6]. IBS is a complex functional gut disorder of unknown origin. Several factors, including gastrointestinal hypersensitivity, motility, low-grade inflammation, and psychosocial factors seem to interplay to produce abdominal symptoms. In the last few years, increasing evidence for the role of gut bacteria in the control of gut function has been recognized[3], and recent studies using novel techniques for the quantification of gut microflora have demonstrated differences in the flora of patients with IBS compared to healthy subjects[7]. In parallel, several publications during the last decade have shown that changes in gut microflora, by supplementation of probiotic bacteria, may have beneficial effects in IBS symptoms[8,9]. However, despite deterioration in quality of life being one of the main health-related problems for IBS patients, the vast majority of published controlled trials assess the effects of probiotics on abdominal symptoms[8,9], whereas the effect of probiotics on IBS-related quality of life remains unclear[10].

We designed a pilot clinical trial with the main objective being to determine the dose-related effects of a novel probiotic combination on IBS-related quality of life. Because the effects of probiotics depend on the specific bacteria combinations used, we administered a mixture of equal parts of three probiotic bacteria: two Lactobacillus plantarum (CECT7484 and CECT7485) and one Pediococcus acidilactici (CECT7483). This formula was chosen among more than 100 strains of lactic acid bacteria due to their ability to survive gut passage and adhere to intestinal mucus in vitro. Moreover, when combined, the three strains produced significant amounts of butyric, propionic, and acetic acid in a ratio similar to that found in the healthy gut[11], and reduced inflammation and diarrhea in two different animal models of gut inflammation (J. Espadaler, personal communication). IBS-related quality of life was assessed using a specific questionnaire (IBS-QoL) previously translated and validated into Spanish[12]. As secondary objectives, we evaluated the effect of probiotic intake on gut related anxiety and global symptom relief by means of specific questionnaires[13,14].

A total of 84 patients (53 female, 31 male) aged between 20 and 70 years were enrolled in the study from January 2010 to December 2011. All patients met Rome-III criteria for IBS with diarrhea. Inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease were excluded with clinical and analytical data, including blood chemistry, CRP, and tissue anti-transglutaminase antibodies. Subjects suffering from chronic or acute illness that could interfere with the study, that were taking medications that could interfere in the study (including anti-inflammatory drugs, PPIs, antidepressants, anti-diarrheal, prokinetics, and antispasmodic agents), and patients who consumed antibiotics or probiotics in the four weeks prior to entering into the study were excluded. Pregnant or lactating women were also excluded.

If the subjects fulfilled all the inclusion and exclusion criteria no run-in period was considered, and patients entered the randomization period immediately.

All subjects gave written informed consent to participate. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, adhered to the CONSORT 2010 statement (http://www.consort-statement.org), and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Hospital Puerta de Hierro (Madrid, Spain), and of Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol (Badalona, Spain).

We used a combination of three strains of lactic acid bacteria: two Lactobacillus plantarum (CECT7484 and CECT7485) and one Pediococcus acidilactici (CECT7483). Two different doses of this combination were administered in separate groups of subjects: a high dose combination (effective dose 1-3 × 1010 cfus/capsule throughout the study) and a low dose combination (effective dose 3-6 × 109 cfus/capsule throughout the study). Concentration of viable cells was measured from probiotic preparation at the beginning and end of the study. The proportion of the three strains was the same in both doses (1:1:1). Placebo capsules were indistinguishable in form, color, and taste to the capsules containing bacteria. Capsules were stored for stability analyses at 25 °C and 65% relative humidity in stability chambers following ICH guidelines.

The study was designed as a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled intervention clinical trial with three parallel arms. Randomization lists were computer generated, and identical capsules containing the allocated treatment and blisters were produced by AB-biotics, so that both patients and physicians were blinded to the actual treatment given to each patient. Each patient was randomly allocated to one of the following treatments for 6 wk (42 d): (1) I.31 high dose capsule once daily; (2) I.31 low dose capsule once daily; and (3) a placebo capsule once daily.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the improvement in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at the end of the 6-wk study period, assessed with a specific questionnaire for IBS: the validated Spanish version[12] of the IBS-QoL[15]. Scores of IBS-QoL were standardized to a 0-100 scale. Improvement was calculated as the difference between the midpoint (day 21) or endpoint (day 42) scores and the baseline score for each group. All subjects with information in 1 or more of the 9 individual domains of the IBS-QoL questionnaire were included in the ITT analysis.

The validated Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI) scale[13] was used to assess anxiety specifically related to gastrointestinal sensations and symptoms. VSI improvement was calculated as the difference between the baseline score and the midpoint (day 21) or endpoint (day 42) scores for each group.

Symptom relief was evaluated with a 5-point scale as proposed by Müller-Lissner et al[14]: 1, symptom worsening; 2, no relief; 3, somewhat relieved; 4, considerably relieved; and, 5, completely relieved. Patients filled IBS-QoL and VSI questionnaires at baseline (day 1) and during follow-up visits on days 21 and 42. Symptom relief was calculated in each individual as the weekly average of the scores recorded during the last four weeks of treatment for each group. All subjects with information in 1 or more weeks over the last 4 were included in the analysis. Patients were defined as responders when answered “considerably relieved” or “completely relieved” at least 50% of the time during the last four weeks, as recommended by EMA guideline CPMP/EWP/785/97[14].

The empty blisters delivered by patients were counted to confirm treatment compliance. No analysis of fecal samples was performed.

Adverse events were monitored following the directives of the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System for standard clinical trials with drugs.

Results were expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed on the ITT population. For between-group comparisons of quantitative variables, an ANOVA test was used if application conditions were satisfied according to Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances and the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality; alternatively a non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) was used. Reported P values have been corrected using the Bonferroni-Holm method for multiple comparisons in ANOVA and Kruskall-Wallis post-hoc tests. Correlation between qualitative variables was tested using t test or Mann-Whitney U test depending on data normality, and correlation between quantitative variables was likewise tested using Pearson’s or Spearman’s rank test.

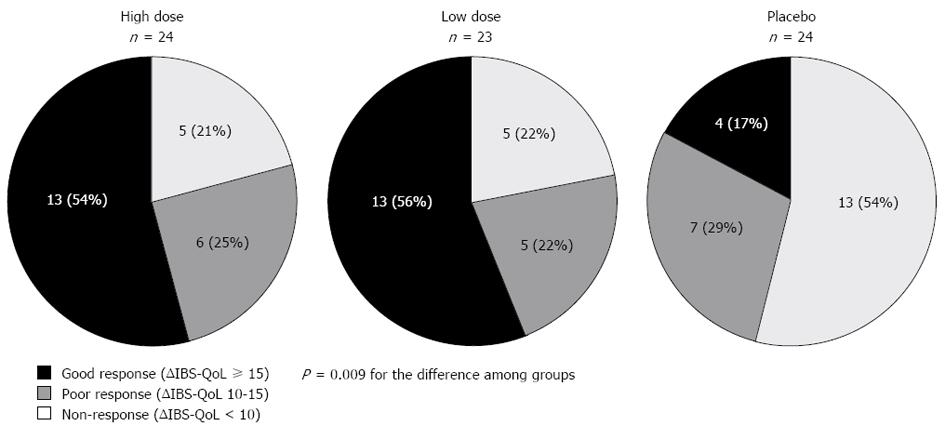

According to the increment in IBS-QoL, patients were divided as good responders (IBS-QoL score increment ≥ 15 points), poor responders (IBS-QoL score increment between 10 and 15 points), and non-responders (IBS-QoL score increment < 10 points), and contingency tables were constructed. Differences between groups were tested using the χ2 test.

The study was powered to detect an increment of ≥ 10 points over placebo in the 0 to 100 IBSQoL scale at the end of the study period, with α = 0.05 and β = 0.80, a drop-out rate of ≤ 20% and SD = 10, resulting in a target n of 33 subjects per arm, after adjusting for comparisons between the three arms.

At baseline, there were no differences between the patients allocated to the different treatment groups in none of the measured parameters (Table 1). The number of subjects lost to follow-up or with insufficient data in the questionnaires was low for all parameters in all groups, and valid data could be obtained from the majority of patients in all treatment groups at the end of the study (Figure 1).

| High dose (n = 28) | Low dose (n = 27) | Placebo (n = 29) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 47.5 ± 13.1 | 46.3 ± 11.6 | 46.5 ± 13.1 | NS |

| Male/female | 9/19 | 7/20 | 15/14 | NS |

| BMI | 24.7 ± 3.9 | 25.6 ± 5.1 | 26.4 ± 5.2 | NS |

| IBSQoL | 54.2 ± 16.1 | 50.6 ± 12.0 | 54.6 ± 18.5 | NS |

| VSI | 43.0 ± 13.5 | 45.5 ± 11.0 | 41.2 ± 15.3 | NS |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 95.1 ± 13.8 | 91.9 ± 27.9 | 95.1 ± 14.5 | NS |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 200.6 ± 39.6 | 200.0 ± 34.2 | 205.1 ± 30.5 | NS |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 113.0 ± 45.3 | 102.0 ± 45.6 | 108.2 ± 50.2 | NS |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 56.6 ± 35.9 | 76.0 ± 39.7 | 72.2 ± 45.5 | NS |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.79 ± 0.14 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.18 | NS |

| GGT (IU/L) | 18.1 ± 10.8 | 19.0 ± 9.9 | 22.1 ± 15.6 | NS |

| GOT (IU/L) | 19.6 ± 7.9 | 20.3 ± 9.5 | 18.3 ± 4.1 | NS |

| GPT (IU/L) | 21.4 ± 13.4 | 17.9 ± 6.6 | 20.1 ± 10.6 | NS |

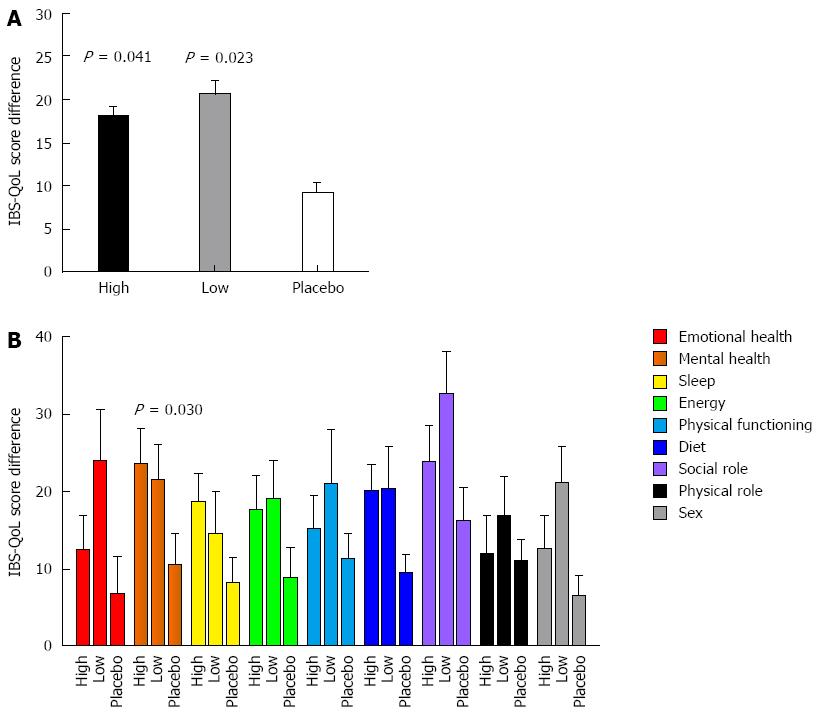

All groups of patients showed an improvement in IBS-QoL after 3 wk of treatment, and statistically significant differences between the treatment groups were observed after three and six weeks of supplementation (P = 0.012 and P = 0.008, respectively). After three weeks, mean score increments were 18 ± 2 for the group allocated to high dose probiotics (P = 0.017 vs placebo), 17 ± 3 for the low dose group (P = 0.071 vs placebo), and 12 ± 2 for the placebo group. Differences among groups became even more significant after six weeks of supplementation, and both the high and the low dose groups (18 ± 3 and 22 ± 4, respectively), achieved a significant greater increment in IBS-QoL compared to 9 ± 3 in the placebo group (P = 0.041 and P = 0.023, for the high and low dose vs placebo, respectively; Figure 2A) without statistical differences between the high and the low probiotic doses (P = 0.392). IBS-QoL data did not follow a normal distribution, so we used a non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskall-Wallis test). A linear mixed model with repeated measures, adjusted for age, BMI, and sex, obtained a P = 0.024.

Per domain analysis showed a greater improvement in almost all the domains in the patients treated with the probiotic combination (both high and low doses) than in those treated with a placebo (Figure 2B), and this difference reached statistical significance in the Mental Health domain (P = 0.030).

In a post hoc analysis, when the individual response to treatment was analyzed, the number of patients with a good response to the treatment (defined as score improvement ≥ 15 points), was significantly larger in those treated with probiotics (both with the high and low dose) than in those treated with placebo (P = 0.009; Figure 3). Slightly changing this cutoff (e.g., ≥ 14 points or ≥ 16 points) yields similar results (data not shown). Likewise, the number of subjects showing some improvement (defined as score improvement >10 points) was also significantly larger in those treated with probiotics than in those treated with a placebo (P = 0.038; Figure 3).

Despite a fivefold difference in the concentration of probiotic between the high and low doses, no differences in the effect on IBS-QoL could be observed between doses at the end of the study (Figure 2A). When all patients treated with probiotics (high and low dose) are pooled together after 6 wk of treatment, the number of patients needed to treat (NNT) to achieve a good improvement (≥ 15 points increment; i.e., good responders) in health-related quality of life is 2.6 patients.

Gut-related anxiety, as measured with the VSI scale, also showed a significantly greater improvement in patients treated with the probiotic combination for both the high (10 ± 2 score increment; P = 0.033 vs placebo) and the low dose groups (14 ± 2 score increment; P = 0.015 vs placebo) compared to those treated with placebo (7 ± 1 score increment). However, this effect needed a longer time than that observed with IBS-related quality of life, and became evident only after 6 treatment weeks, whereas at three weeks there were no differences between the treatment groups (VSI score increments after three weeks were 6 ± 2, 7 ± 2, and 6 ± 1 for the high dose, low dose, and placebo groups, respectively).

When considering data from the last four weeks of treatment, the number of responders (“considerably relieved” or “completely relieved” at least 50% of the time) was somewhat, but not significantly, greater in both treatment groups (42% in the high dose group, 32% in the low dose group) than in the placebo group (25%; P = 0.467).

No rescue medication was reported to be used by any subject during their participation in the study. No adverse drug reactions were reported following the consumption of probiotic or placebo capsules. Additionally, the drop-out rate did not differ between study groups (3 patients in the high and low dose groups, and 5 patients in the placebo group). A small increment of liver enzyme levels (less than 3 times over normal ranges) was observed in 4 patients: two in the high dose group, one in the low dose, and one in the placebo group. Of note, one patient in the high probiotic dose group and the one in the low probiotic dose group already had liver enzyme levels above the normal range at baseline.

The most relevant finding of the present study is that a new combination of 3 different probiotic bacteria (I.31 probiotics) taken daily for 6 wk had a positive impact on IBS-related quality of life, with the effect not being related to the dose of probiotics. The higher probiotic dose appeared to achieve a slightly faster effect on IBS-QoL, which was significantly larger than in the placebo group after 3 wk of treatment. However, at the end of the study no differences could be observed between doses, neither in quality of life nor in the other parameters measured. These results are a bit surprising, given that the higher dose contained 5 times more viable probiotic cells than the lower dose, and suggests that a plateau effect could have been achieved at the lower dose.

IBS is a complex, heterogeneous condition of unknown origin, with a variety of different factors involved in symptom generation. These include: increased visceral sensitivity[16], altered motility and gas transport[17], low-grade inflammation[18], psychological disturbances[19], and early life experiences[20]. The final symptoms present in each individual patient and the severity of the disease are the result of the interplay between all these factors[21]. IBS has an important impact in the quality of life of the patients[2,3], and the degree of alteration of quality of life is closely related to the severity of IBS in each individual patient[6]. Hence, in the absence of a curative strategy, improvement of quality of life should be an important objective of IBS treatment. IBS-QoL was evaluated using a specific questionnaire[15] that was previously translated and validated to the Spanish language[12]. This questionnaire has been previously used in large clinical trials to assess the effect of drugs in IBS-QoL[22]. We decided that a cut-off of 15 points in IBS-QoL score improvement should define good responders, and a cut-off of 10 points should distinguish responders from non-responders. These cut-off points, which are arbitrary, are in the same line as used in other studies assessing the clinical impact of treatments on QoL[23]. Using this methodology, we found that 55% of patients treated with probiotics (high as well as low dose) were good responders, whilst only 17% of placebo-treated patients did, and more than 75 % of the patients were responders. Hence, the benefit of probiotic treatment on IBS-QoL was not only statistically significant, but also clinically relevant.

When the effect over the specific domains was analyzed, we found an improvement of quality of life in all the domains, but this difference was only statistically significant for the mental status domain.

Improvement of quality of life was associated to a significant improvement in gut related anxiety, as measured by a specifically developed questionnaire: VSI[13]. This finding is also relevant, because mental disorders, like anxiety and depression, are often present in IBS and may have an impact on the severity of the disease and quality of life[6,24,25]. VSI has been shown to be a strong predictor of current IBS symptom severity[13,24]. Improvement in VSI took longer than IBS-QoL improvement, and became evident only after 6 wk of treatment, suggesting that other factors influenced IBS-QoL.

Abdominal symptom relief during probiotic treatment was somewhat greater, but not statistically significant, in patients treated with probiotics. These differences were in line with previous studies showing a modest effect of probiotics on individual symptoms[9,10]. The lack of effect of probiotics on symptom relief may be due to the small number of subjects included in the study. The sample size in this pilot study was specifically powered to detect differences in IBS-QoL. In fact, based on data from previous clinical studies with probiotics[9], over 100 patients per arm should have been included in order to detect a significant difference in global symptom relief, with α = 0.05 and β = 0.80 after adjusting for comparisons between three arms and accounting for drop-outs. However, considering this limitation of the present study, our data suggest that the effect of probiotics on IBS seems not to be limited to the area of GI-symptoms, but is also evident for other aspects outside the abdomen, like mental health status, gut related anxiety, and IBS-related quality of life.

During the last few years, the role of intestinal microbiota in the modulation of gut function has received increasing attention. Studies in mice showed that intestinal microbiota modulates immune and smooth muscle function, epithelial cell permeability, enteric neurotransmission, and visceral sensitivity[26]. Most of these factors are altered to some degree in patients with IBS[4,27-29]. Modulation of intestinal microflora by probiotics can decrease visceral sensitivity in mice[30,31] and the inflammatory responses in humans, an effect that correlated with symptom improvement in IBS patients[32]. However, the effects of intestinal microbiota go beyond the limits of the GI-tract, and several studies suggest that they are also involved in modulation of body weight, cutaneous perception, and behavior[33-35]. Moreover, a recent study from McMaster shows that intestinal microbiota can influence the central nervous system and behavior in adult mice in the absence of discernible changes in local or circulating cytokines or specific gut neurotransmitter levels, suggesting the existence of a direct gut microbiota-brain axis[36]. Hence, it seems possible that a direct effect of probiotics on the central nervous system could also have contributed to the effects of probiotics in the present study.

Our results do not provide evidence for a dose-related effect of the tested probiotics. The explanation for such an outcome is unclear, but may be due to the intrinsic nature of probiotics, which may not follow the typical pharmacological rules or to a saturation of the effect. The effects of probiotics are not universal for all bacteria, not even for strains of the same species, as each specific bacterial strain may have particular effects on gut function, which is probably also true for other functions outside the GI-tract. Likewise, there may be synergistic or antagonistic effects when a bacterial combination is administered[8]. In the present study, we used a mixture of three probiotic bacteria, two strains of Lactobacillus plantarum (CECT7484 and CECT7485) and one Pediococcus acidilactici (CECT7483), which was previously found to reduce inflammation and diarrhea in two different animal models of gut inflammation. Using this formula, we found a rapid and clinically relevant effect of the probiotic combination on IBS-related quality of life, which was associated to an improvement of gut related anxiety, but not to similar relief in abdominal symptoms. Hence, although our study was not designed to determine mechanistic factors involved in the effects induced by probiotics, our results suggest that the mechanisms involved in improvement of IBS-related quality of life may include both local and central effects. If these results were reproduced in larger studies, they open the possibility of developing treatment strategies using probiotics that are not only addressed against the abdominal symptoms of patients with functional gut disorders, but can also influence other important aspects of the disorder and other conditions often associated with IBS like behavior, anxiety, or depression.

In conclusion, we found that a new combination of three different probiotic bacteria was superior to placebo in improving IBS-related quality of life in patients with IBS and diarrhea. After 6 wk of treatment, the difference was evident in both high and low doses of bacteria, and the increment in quality of life was mainly due to an increment in the mental status domain and an associated to an improvement in gut related anxiety. Hence, this probiotic combination can be useful for the treatment of patients with IBS that impacts their quality of life.

The authors thank the Translation Service of the Autonoma University of Barcelona for English editing of the manuscript.

To determine the dose-related effects of the novel probiotic combination I.31 on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-related quality of life (IBS-QoL).

Changes in gut microflora, by supplementation of probiotic bacteria, may have beneficial effects in IBS symptoms.

I.31 probiotic formula had effects on IBS-quality of life at 3 and 6 wk, as well as on Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI) at 6 wk, but had only a modest effect on abdominal symptoms.

This probiotic combination can be useful for the treatment of patients with IBS that impacts their quality of life.

IBS-QoL is a standardized score to a 0-100 scale. The VSI scale is used to assess anxiety specifically related to gastrointestinal sensations and symptoms.

This is a study on the effects of IBS symptoms of a probiotic formula consisting of three different probiotic strains. Data are interesting, but the presentation of the data needs to be more focused.

P- Reviewers: Carter D, Iovino P, Ohman L, Rahimi R S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1416] [Article Influence: 108.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654-660. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Simrén M, Svedlund J, Posserud I, Björnsson ES, Abrahamsson H. Health-related quality of life in patients attending a gastroenterology outpatient clinic: functional disorders versus organic diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:187-195. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Paré P, Gray J, Lam S, Balshaw R, Khorasheh S, Barbeau M, Kelly S, McBurney CR. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1726-1735; discussion 1710-1711. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, Kahler KH, Frech F, Groves D, Ofman JJ. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S17-S26. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Coffin B, Dapoigny M, Cloarec D, Comet D, Dyard F. Relationship between severity of symptoms and quality of life in 858 patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004;28:11-15. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Rajilić-Stojanović M, Biagi E, Heilig HG, Kajander K, Kekkonen RA, Tims S, de Vos WM. Global and deep molecular analysis of microbiota signatures in fecal samples from patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1792-1801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 685] [Cited by in RCA: 773] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, Spiegel BM, Spiller RC, Vanner S, Verdu EF, Whorwell PJ, Zoetendal EG. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut. 2013;62:159-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 655] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 54.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moayyedi P, Ford AC, Talley NJ, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Brandt LJ, Quigley EM. The efficacy of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Gut. 2010;59:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ortiz-Lucas M, Tobías A, Saz P, Sebastián JJ. Effect of probiotic species on irritable bowel syndrome symptoms: A bring up to date meta-analysis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:19-36. [PubMed] |

| 11. | D’Argenio G, Mazzacca G. Short-chain fatty acid in the human colon. Relation to inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;472:149-158. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Badia X, Herdman M, Mearin F, Pérez I. Adaptación al español del cuestionario IBSQoL para la medición de la calidad de vida en pacientes con síndrome de intestino irritable. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2000;92:637-643. |

| 13. | Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, Wiklund I, Naesdal J, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. The Visceral Sensitivity Index: development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:89-97. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Müller-Lissner S, Koch G, Talley NJ, Drossman D, Rueegg P, Dunger-Baldauf C, Lefkowitz M. Subject’s Global Assessment of Relief: an appropriate method to assess the impact of treatment on irritable bowel syndrome-related symptoms in clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:310-316. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hahn BA, Kirchdoerfer LJ, Fullerton S, Mayer E. Evaluation of a new quality of life questionnaire for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:547-552. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Serra J, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Impaired transit and tolerance of intestinal gas in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2001;48:14-19. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Serra J, Villoria A, Azpiroz F, Lobo B, Santos J, Accarino A, Malagelada JR. Impaired intestinal gas propulsion in manometrically proven dysmotility and in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:401-46, 401-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Barbara G, De Giorgio R, Stanghellini V, Cremon C, Corinaldesi R. A role for inflammation in irritable bowel syndrome? Gut. 2002;51 Suppl 1:i41-i44. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Levy RR, Feld AD, Turner M, Von Korff M. Comorbidity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2767-2776. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MA, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE. Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:765-774; quiz 775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Drossman DA, Chang L, Bellamy N, Gallo-Torres HE, Lembo A, Mearin F, Norton NJ, Whorwell P. Severity in irritable bowel syndrome: a Rome Foundation Working Team report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1749-1759; quiz 1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Watson ME, Lacey L, Kong S, Northcutt AR, McSorley D, Hahn B, Mangel AW. Alosetron improves quality of life in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:455-459. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Carson RT, Tourkodimitris S, Lewis BE, Johnston JM. Small bowel II: PWE-127 Two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials of linaclotide in adults with irritable bowel syndrome: Effects on quality of life. Gut. 2011;61:A348-A349. |

| 24. | Jerndal P, Ringström G, Agerforz P, Karpefors M, Akkermans LM, Bayati A, Simrén M. Gastrointestinal-specific anxiety: an important factor for severity of GI symptoms and quality of life in IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:646-e179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sugaya N, Nomura S, Shimada H. Relationship between cognitive factors and anxiety in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19:308-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hooper LV, Wong MH, Thelin A, Hansson L, Falk PG, Gordon JI. Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science. 2001;291:881-884. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Eugenio MD, Jun SE, Cain KC, Jarrett ME, Heitkemper MM. Comprehensive self-management reduces the negative impact of irritable bowel syndrome symptoms on sexual functioning. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1636-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Farndale R, Roberts L. Long-term impact of irritable bowel syndrome: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2011;12:52-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Drossman D, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Whitehead WE, Dalton CB, Leserman J, Patrick DL, Bangdiwala SI. Characterization of health related quality of life (HRQOL) for patients with functional bowel disorder (FBD) and its response to treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1442-1453. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bravo JA, Forsythe P, Chew MV, Escaravage E, Savignac HM, Dinan TG, Bienenstock J, Cryan JF. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16050-16055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2500] [Cited by in RCA: 2637] [Article Influence: 188.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Verdú EF, Bercik P, Verma-Gandhu M, Huang XX, Blennerhassett P, Jackson W, Mao Y, Wang L, Rochat F, Collins SM. Specific probiotic therapy attenuates antibiotic induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. Gut. 2006;55:182-190. [PubMed] |

| 32. | O’Mahony L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, Hurley G, Luo F, Chen K, O’Sullivan GC, Kiely B, Collins JK, Shanahan F. Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:541-551. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915-1920. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Amaral FA, Sachs D, Costa VV, Fagundes CT, Cisalpino D, Cunha TM, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ, Silva TA, Nicoli JR. Commensal microbiota is fundamental for the development of inflammatory pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2193-2197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lyte M, Varcoe JJ, Bailey MT. Anxiogenic effect of subclinical bacterial infection in mice in the absence of overt immune activation. Physiol Behav. 1998;65:63-68. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Bercik P, Denou E, Collins J, Jackson W, Lu J, Jury J, Deng Y, Blennerhassett P, Macri J, McCoy KD. The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:599-609, 609.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1135] [Cited by in RCA: 1216] [Article Influence: 86.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 783] [Cited by in RCA: 1083] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |