Published online Jul 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8292

Revised: March 2, 2014

Accepted: April 5, 2014

Published online: July 7, 2014

Processing time: 159 Days and 5.8 Hours

Bleeding from gastro-esophageal varices can often present as the first decompensating event in patients with cirrhosis. This can be a potentially life threatening event associated with a 15%-20% early mortality. We present a rare case of new onset ascites due to intra-abdominal hemorrhage from ruptured mesenteric varices; in a 37 years old male with newly diagnosed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis induced cirrhosis as the first decompensating event. The patient was successfully resuscitated with emergent evacuation of ascites for diagnosis, identification and control of bleeding mesenteric varices and eventually orthotopic liver transplantation with successful outcome. Various clinical presentations, available treatment options and outcomes of ectopic variceal bleeding are discussed in this report.

Core tip: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) related cirrhosis of the liver is an emerging disease. With the advent of new therapies for hepatitis C and the potential for cure, NASH will most likely be the leading cause of decompensated liver disease in the future. We present a rare case of hemorrhagic ascites from ectopic variceal rupture as the initial decompensating event in a young patient with a recent diagnosis of cirrhosis from NASH. A multidisciplinary, methodical treatment plan was undertaken, culminating in orthotopic liver transplantation and successful outcome. We briefly discuss presentation, diagnosis and management of ectopic variceal bleeding, which is not so commonly encountered in routine clinical practice in this case report.

- Citation: Edula RG, Qureshi K, Khallafi H. Hemorrhagic ascites from spontaneous ectopic mesenteric varices rupture in NASH induced cirrhosis and successful outcome: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(25): 8292-8297

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i25/8292.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8292

Ectopic variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with significant portal hypertension is a well-known although rare complication, accounting for about 5% of all variceal bleeding[1]. It can often present as obscure gastrointestinal bleed depending on location of varices. Unlike esophageal variceal bleeding, for which definite guidelines exist in terms of management and surveillance, ectopic varices due to their sporadic occurrence and varying presentations depending on location, do not have specific guidelines in terms of management. Recognizing the various presentations of ectopic variceal bleed is vital to the survival of these patients and a high degree of suspicion is necessary for timely diagnosis and effective management. Hemorrhagic ascites presenting as a complication of intraperitoneal ectopic variceal rupture is a dreaded and potentially fatal complication, management of which requires a multi-disciplinary approach along with timely recognition and diagnosis.

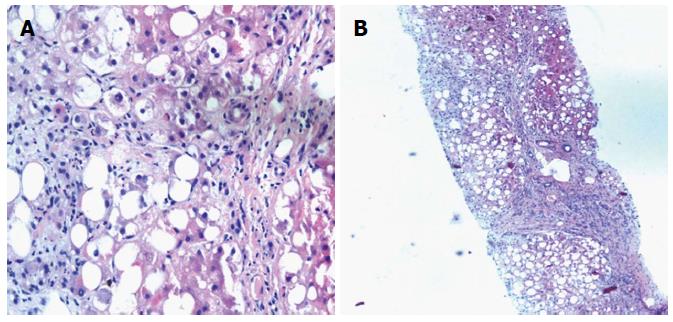

A 37 years old Caucasian male presented to the emergency room with a 3 day history of right upper and lower quadrant abdominal pain with distension. Physical examination revealed palmar erythema, icterus and moderate ascites with tenderness in the right lower quadrant. He was tachycardic but hemodynamically stable at presentation with a low grade fever. Review of his recent medical records revealed that he was newly diagnosed with NASH cirrhosis at an outside facility, about 3 mo prior to this presentation, as a part of work up of abdominal pain which demonstrated abnormal appearing liver. Subsequent workup and liver biopsy (Figure 1) suggested the diagnosis of NASH related cirrhosis after ruling out all other etiologies. He did not have any abdominal surgeries in the past and was not on any medications.

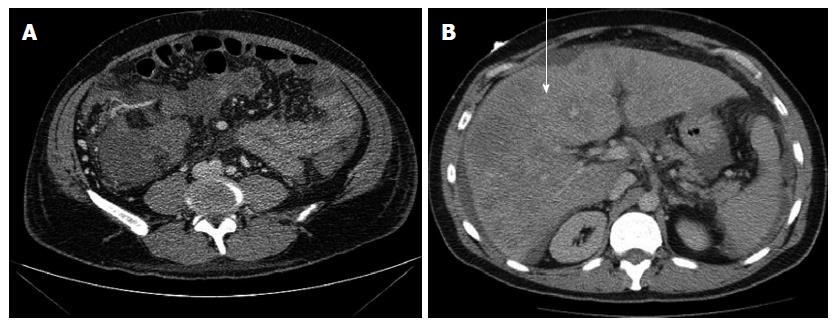

Initial laboratory data at the time of this presentation showed; Hb: 8.7 gm/dL, Hct: 25.2, WCC: 17.68 with neutrophilia, platelets: 149 and INR: 1.81. Complete metabolic panel revealed Cr: 0.97 mg/dL, protein: 6.7 gm/dL, albumin: 2.9 gm/dL, total bilirubin: 18.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin: 13.2 mg/dL, Alkp: 164U/L, AST: 140U/L, ALT: 44U/L and a MELD score of 24. Computerized tomography of the abdomen with contrast (Figure 2) revealed lobulated contour of the liver consistent with cirrhosis (arrow), severe porto-systemic collateral circulation with esophageal varices, mesenteric stranding and small to moderate volume ascites with dependent hyper dense areas within the fluid suggestive of hemorrhagic component. Patient underwent diagnostic paracentesis with removal of 6 liters of grossly bloody fluid consistent with intra-peritoneal hemorrhage.

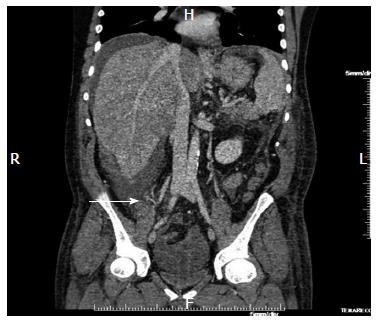

Upon admission patient was initially resuscitated with blood products, fluids, correction of coagulopathy and empirical antibiotics were initiated. His clinical condition continued to worsen with drop in blood pressure and hemoglobin. A CTA and CTV of the abdomen were performed (Figure 3) to identify the source of bleeding. This revealed right abdominal mesenteric varices with a focal area of more consolidated abnormal enhancement in the right lower quadrant (arrow). A possible nidus of venous malformation between superior mesenteric vein and right common iliac vein varices was suggested with more hyper dense ascites adjacent to this suggestive of possible origin of hemoperitoneum.

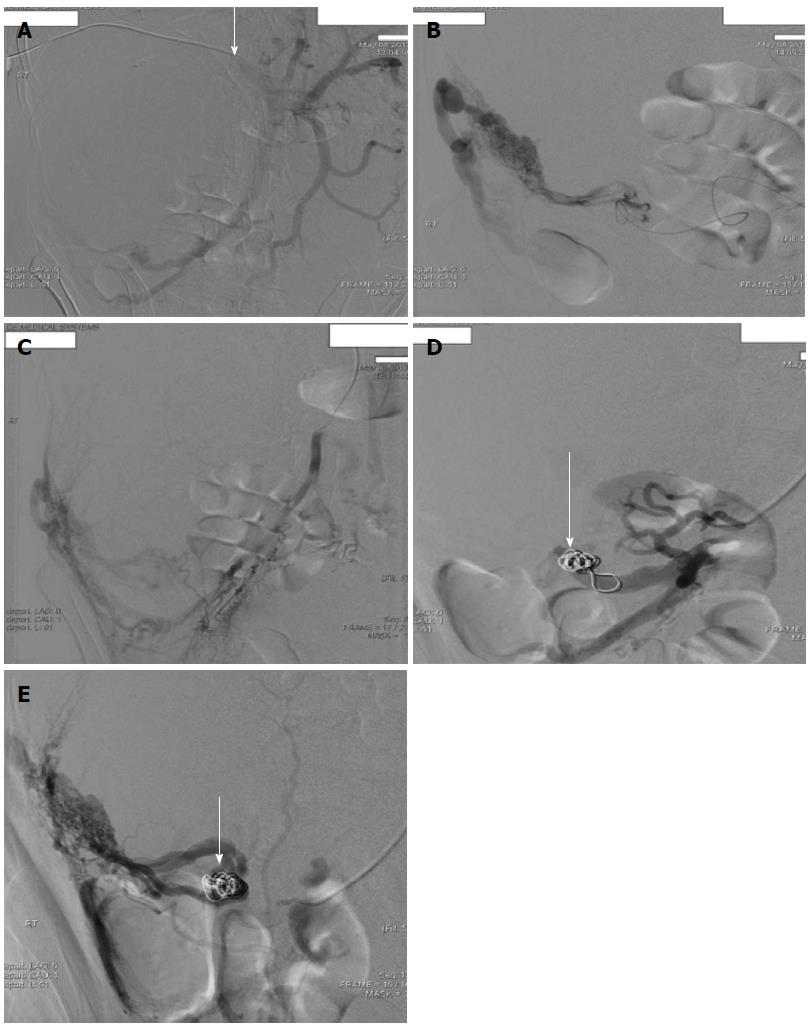

The patient underwent an angiogram by intervention radiology with trans- hepatic access of the portal vein, portal venogram, superior mesenteric venogram and coil embolization of colonic branch of superior mesenteric vein and cecal branch of the superior mesenteric vein (Figure 4). There were no immediate complications. The procedure controlled his intra-abdominal bleeding and he remained hemodynamically stable. Over the next 48 h he developed first episode of hematochezia with hypotension. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy revealed large esophageal varices with evidence of recent bleeding. He underwent an emergent Trans jugular Intrahepatic Porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) procedure with successful decompression of portal system. The hepatic venous pressure gradient was reduced from 17 to 9 mmHg post procedure. He eventually underwent successful orthotopic liver transplantation after appropriate evaluation of decompensated end stage liver disease during the same presentation and was discharged home in a stable condition.

Ectopic varices are defined as large porto-systemic venous collaterals occurring anywhere in the abdomen other than the cardio-esophageal region. These are uncommon and account for less than 5% of all cases of variceal bleeding[1,2]. Most patients show presence of esophageal varices simultaneously and may have a history of treatment for them in the form of endoscopic intervention or primary prophylaxis. They have been reported to occur at numerous sites which include 17% in the jejunum or ileum, 17% in the duodenum, 14% in the colon, 8% in the rectum and 9% in the peritoneum in a retrospective study[3]. Ectopic varices may bleed even when portal venous pressure is low. They have a 4 fold increased risk of bleeding when compared to esophageal varices and can have a mortality rate as high as 40%[2].

Clinical presentation of ectopic variceal bleed is based on location of the varices. Luminal varices are fortunately more common, usually easier to detect and manifest earlier than the non-luminal ectopic varices[4]. Clinical manifestations include overt GI bleeding of obscure origin, occult GI bleeding, accidental finding, iron deficiency anemia, hematemesis, hematochezia, hemoperitoneum, hypovolemic shock, hemorrhagic pleural effusion and sometimes diagnosis is made only at autopsy[5]. Ectopic varices should be considered in all patients with portal hypertension and GI bleeding, if both upper and lower endoscopies failed to show obvious source. Awareness of the condition is a necessity for any physician dealing with GI bleeding, especially in the setting of cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Diagnosis of ectopic variceal bleed in a timely manner is important due to the high mortality rate associated with the condition. Endoscopic and angiographic techniques may be required as they can appear as filling defects in barium studies of the bowel and maybe misdiagnosed as polyps or tumors[6]. Abdominal wall varices usually rupture externally and can be easily diagnosed. Mesenteric, diaphragmatic, falciform ligament, splenic ligament and rectovesical varices may rupture into the peritoneal cavity causing internal bleeding and fatal outcomes[7,8]. This requires high degree of clinical suspicion when presentations include rapid accumulation of ascites, reduction in hematocrit and signs of hypovolemic shock. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis aids in the diagnosis and confirmed by detection of bloody ascites at paracentesis. Angiographic techniques which include percutaneous transhepatic portography, transjugular transhepatic portography, splenic portography and umbilical vein catheterization can be used to identify the location of bleeding, extent of portosystemic collaterals, direction of flow and simultaneously measure the pressure in the portal venous system[9-11].

There are no large randomized controlled trials that have previously addressed the therapeutic modalities for ectopic varices. Most of the available knowledge is obtained from small case series, case reports and mini reviews. The management of ectopic varices requires a multidisciplinary team of hepatologists, gastroenterologists, surgeons and interventional radiologists. Due to the diversity of their location and clinical presentation it is very difficult to draw treatment guidelines. Optimal treatment depends on location of varices, patient’s condition and the availability of local expertise and resources[4]. Initial management includes appropriate resuscitation, emergent evaluation to localize site and source of bleeding followed by suitable treatment. The use of vasoactive medications like somatostatin (octreotide) and terlipressin to reduce splanchnic blood flow and variceal pressure may be of benefit as in patients with bleeding from gastro-esophageal varices[12,13]. No solid data exists on the role of beta blockers in the long term management of ectopic varices. Case reports have been contradictory as to their effectiveness[14-16]. Endoscopically accessible varices can be treated by band ligation or sclerotherapy[17-19]. Those which are not accessible by endoscopic techniques can be treated by interventional radiology and may include coil embolization, balloon occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration and if unable to access the site a TIPS shunt to decompress the portal pressure could be a lifesaving intervention[20-24]. Ultimately the long term survival of these patients is dependent on their liver function and liver transplantation should be considered as a definitive therapy after appropriate evaluation as in our case report.

In conclusion, Ectopic variceal bleeding is a rare event unlike esophageal variceal bleeding, for which specific treatment guidelines do not exist. A high degree of suspicion is essential for the entity as a delay in diagnosis could lead to fatal consequences. Due to the lack of specific guidelines in management, a multi-disciplinary approach utilizing local expertise and resources has been recommended. Early diagnosis, prompt resuscitation followed by appropriate intervention is crucial in the management of these patients, who have severe portal hypertension and are already coagulopathic from end stage liver disease. Appropriate referral to a tertiary care center should be initiated when resources are not available locally and liver transplantation should be considered as a definitive treatment to give them the best chance of long term survival.

A 37-year-old male with recently diagnosed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis cirrhosis presented with abdominal pain and distension.

Palmar erythema, scleral icterus, shifting dullness on abdominal percussion and right lower quadrant tenderness.

Ascites from portal hypertension, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, intra-abdominal hemorrhage from variceal rupture, hepatocellular carcinoma rupture and perforated viscous.

Hemoglobin: 8.7 gm/dL, WCC: 17.6, platelets: 149, INR: 1.8, bilirubin: 18.2mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase: 164, AST: 140, ALT: 44, creatinine: 0.97mg/dL and MELD score: 24.

CT/CTA/CTV of abdomen: Cirrhosis, ascites, right abdominal mesenteric varices with focal area of enhancement in the right lower quadrant indicating hemoperitoneum.

Paracentesis revealed hemorrhagic ascites. Trans-hepatic portal vein angiogram revealed mesenteric varices with bleeding from colonic branch and cecal branch.

Coil embolization of bleeding mesenteric varices by intervention radiologist, Trans jugular Intrahepatic Porto-systemic shunt for esophageal variceal bleed and eventually orthotopic liver transplantation for end stage liver disease.

Ectopic variceal bleed accounts for about 5% of variceal hemorrhage and high degree of suspicion is necessary in cirrhotics with obscure bleeding.

Ectopic varices are porto-systemic collaterals occurring anywhere in the abdomen other than cardio-esophageal region. Orthotopic liver transplant is replacement of complete liver by donor liver in the normal anatomical position.

This case report not only describes a very rare presentation of decompensated cirrhosis, but also managed successfully in a multi-disciplinary fashion utilizing multiple medical and surgical specialists.

This article reported successful management of ectopic mesenteric variceal rupture and is an important diagnosis to consider in massive obscure bleeding in cirrhotic patients.

P- Reviewers: Dirchwolf MM, El-Raziky ES, Narciso-Schiavon JL, Ruiz-Margain A, Tsuchiya T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Kinkhabwala M, Mousavi A, Iyer S, Adamsons R. Bleeding ileal varicosity demonstrated by transhepatic portography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:514-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khouqeer F, Morrow C, Jordan P. Duodenal varices as a cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Surgery. 1987;102:548-552. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M. Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:322-334. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Hashiguchi M, Tsuji H, Shimono J, Azuma K, Fujishima M. Ruptured duodenal varices: an autopsy case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1751-1754. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Zaman L, Bebb JR, Dunlop SP, Jobling JC, Teahon K. Familial colonic varices--a cause of “polyposis” on barium enema. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e17-e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Olusola BF, McCashland TM, Seemayer TA, Sorrell MF. Rectovesical ectopic varix intraperitoneal hemorrhage with fatal outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramchandran TM, John A, Ashraf SS, Moosabba MS, Nambiar PV, Shobana Devi R. Hemoperitoneum following rupture of ectopic varix along splenorenal ligament in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:91. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Turner MD, Sherlock S, Steiner RE. Splenic venography and intrasplenic pressure measurement in the clinical investigation of the protal venous system. Am J Med. 1957;23:846-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kessler RE, Tice DA, Zimmon DS. Value, complications, and limitations of umbilical vein catheterization. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1973;136:529-535. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Smith-Laing G, Camilo ME, Dick R, Sherlock S. Percutaneous transhepatic portography in the assessment of portal hypertension. Clinical correlations and comparison of radiographic techniques. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:197-205. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Besson I, Ingrand P, Person B, Boutroux D, Heresbach D, Bernard P, Hochain P, Larricq J, Gourlaouen A, Ribard D. Sclerotherapy with or without octreotide for acute variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silvain C, Carpentier S, Sautereau D, Czernichow B, Métreau JM, Fort E, Ingrand P, Boyer J, Pillegand B, Doffël M. Terlipressin plus transdermal nitroglycerin vs. octreotide in the control of acute bleeding from esophageal varices: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 1993;18:61-65. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Wu WC, Wang LY, Yu FJ, Wang WM, Chen SC, Chuang WL, Chang WY. Bleeding duodenal varices after gastroesophageal varices ligation: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2002;18:578-581. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Noubibou M, Douala HC, Druez PM, Kartheuzer AH, Detry RJ, Geubel AP. Chronic stomal variceal bleeding after colonic surgery in patients with portal hypertension: efficacy of beta-blocking agents? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:807-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hsieh JS, Wang WM, Perng DS, Huang CJ, Wang JY, Huang TJ. Modified devascularization surgery for isolated gastric varices assessed by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:666-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shudo R, Yazaki Y, Sakurai S, Uenishi H, Yamada H, Sugawara K, Kohgo Y. Combined endoscopic variceal ligation and sclerotherapy for bleeding rectal varices associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a case showing a long-lasting favorable response. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:661-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bosch A, Marsano L, Varilek GW. Successful obliteration of duodenal varices after endoscopic ligation. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1809-1812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barbish AW, Ehrinpreis MN. Successful endoscopic injection sclerotherapy of a bleeding duodenal varix. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:90-92. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ozaki CK, Hansen M, Kadir S. Transhepatic embolization of superior mesenteric varices in portal hypertension. Surgery. 1989;105:446-448. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Macedo TA, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Ectopic varices in the gastrointestinal tract: short- and long-term outcomes of percutaneous therapy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:178-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dharancy S, Sergent G, Bulois P, Bonnal JL, Golup G, Mauroy B, L’Hermine C, Paris JC. [Bleeding stomal varices treated with embolization and transjugular porto-systemic shunt]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2000;24:232-234. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Zamora CA, Sugimoto K, Tsurusaki M, Izaki K, Fukuda T, Matsumoto S, Kuwata Y, Kawasaki R, Taniguchi T, Hirota S. Endovascular obliteration of bleeding duodenal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:73-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vidal V, Joly L, Perreault P, Bouchard L, Lafortune M, Pomier-Layrargues G. Usefulness of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhotic patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:216-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |