Published online Jul 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8237

Revised: March 30, 2014

Accepted: April 15, 2014

Published online: July 7, 2014

Processing time: 184 Days and 18.6 Hours

AIM: To determine quality of life improvement in choledocholithiasis patients who underwent endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) versus open choledochotomy (OCT).

METHODS: Eligible choledocholithiasis patients (n = 216) hospitalized in the Changhai Hospital between May 2010 and January 2011 were enrolled into a prospective study using cluster sampling. Patients underwent EST (n = 135) or OCT (n = 81) depending on the patient’s wishes. Patients were followed-up with a field survey and by correspondence. Patients were also given the self-administered Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) to measure patient quality of life before surgery, and at two and six weeks after the procedures.

RESULTS: With respect to baseline patient characteristics, the EST and OCT groups were comparable. After the procedure, gallstones were completely eliminated in all patients. Among 216 eligible patients, 191 patients (88.4%) completed all three surveys, including 118 patients who underwent EST (118/135; 87.4%) and 73 patients who underwent OCT (73/81; 90.1%). EST was associated with a significantly shorter hospital stay than OCT (8.8 ± 6.5 vs 13.9 ± 6.7 d; P < 0.001). The GIQLI score was similar between the EST and OCT groups before cholelithotomy (103.0 ± 15.4 vs 99.7 ± 10.2), but increased significantly in the EST group at two weeks (113.4 ± 12.0 vs 107.2 ± 11.2; P < 0.001) and six weeks (120.7 ± 10.6 vs 116.9 ± 7.5; P < 0.05) after the procedures.

CONCLUSION: EST, compared with OCT, is associated with better postoperative quality of life in patients treated for choledocholithiasis.

Core tip: Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is generally accepted as a safe and effective endoscopic modality in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. However, there are few reports evaluating whether EST contributes to better health-related quality of life improvement in patients undergoing cholelithotomy compared with open choledochotomy (OCT). The present study is the first report regarding the benefits of EST and OCT on gastrointestinal quality of life in a prospective comparative design. The current results show that EST, compared with OCT, is associated with better overall gastrointestinal quality of life in choledocholithiasis patients.

- Citation: Liu F, Bai X, Duan GF, Tian WH, Li ZS, Song B. Comparative quality of life study between endoscopic sphincterotomy and surgical choledochotomy. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(25): 8237-8243

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i25/8237.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8237

Gallstones are a highly prevalent medical condition worldwide, especially in China (10.7%)[1,2]. The prevalence of gallstone disease has increased in the Chinese population over the last two decades because of a more westernized diet and an aging population. In addition, the Chinese population is more prone to choledocholithiasis, or gallstones in the common bile duct (CBD), which accounts for approximately 18% of gallstone cases[3]. Choledocholithiasis is associated with serious medical conditions, such as cholangitis, obstructive jaundice and gallstone pancreatitis, and typically requires surgical intervention.

Open choledochotomy (OCT), the classical surgical approach used to treat choledocholithiasis[4,5], allows for the laparoscopic removal of gallstones through an incision into the CBD. This technique, however, is subject to a high morbidity and mortality rate (1%-2%), as well as a heavy healthcare burden[6-8]. The emergence of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) techniques has challenged OCT as the gold standard in clinical practice. These MIS approaches include endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST)[9], extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy[10], percutaneous transhepatic cholelithotomy[11] and laparoscopic transcholecystic CBD exploration[12]. EST with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is currently preferred in clinical practice, as this endoscopic technique is minimally invasive and has a rapid postoperative recovery after the removal of gallstones[13]. Multiple long-term follow-up studies have validated the safety and efficacy of EST in the treatment of selected choledocholithiasis cases in Western and Eastern Asian populations[14-16]. However, the superiority of EST in general clinical variables does not necessarily indicate that EST is associated with a favorable treatment outcome compared to OCT.

Health-related quality of life (QoL) is a comprehensive measure that evaluates the overall well-being of a subject in physical, mental and social aspects[17]. This measure has been used extensively in randomized controlled trials to optimize treatment algorithms, particularly in chronic medical conditions, such as choledocholithiasis[18,19]. Laparoscopy, another widely accepted MIS technique, has been reported to compare favorably to laparotomy in cholecystectomy patients when measured by QoL[20]. Moreover, the benefit of laparoscopic CBD exploration on gastrointestinal QoL has also been documented in choledocholithiasis patients[21]. Whether EST contributes to a better health-related QoL improvement in cholelithotomy patients compared with OCT has not been well explored. The primary objective of the current study was to investigate whether EST, compared with OCT, was associated with a better gastrointestinal QoL in cholelithotomy patients following treatment.

The Changhai Hospital Institutional Review Board at the Second Military Medical University approved this study protocol. All patients gave written informed consent before study enrollment. Choledocholithiasis patients (n = 232) who underwent elective EST or OCT treatment in Changhai Hospital from May 2010 through January 2011 were prospectively enrolled using cluster sampling. Eligible patients (n = 216) were over 18 years of age, diagnosed radiologically with choledocholithiasis without complicating diseases and were able to give written informed consent. The following exclusion criteria were applied: patients with any malignant disease, a previous history of any physiological or psychiatric disorders, pregnant or lactating, other major surgical or medical complications, unable to respond to the questionnaire or unable to give informed consent in person. An independent research nurse informed patients of the advantages and disadvantages of EST and OCT before treatment. Patients were assigned to either the EST group (n = 135) or OCT group (n = 81), based on each patient’s preference. An assigned team of board-certified gastroenterologists and endoscopists performed EST, whereas an independent surgical team consisting of attending general surgeons and surgical residents performed OCT. Both procedures were completed in accordance with their respective institutional guidelines.

Following enrollment into the study, an independent research nurse documented patient demographic data, including age, sex, marital status, place of residence, educational level and employment status. A validated Chinese version of the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI) was used to assess health-related QoL in patients throughout the study[22]. The GIQLI is a 36-item scale specifically designed to evaluate the QoL in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. This scale consists of five subscales: a self-reported symptom domain (10 items), physical function domain (6 items), mental/emotional function domain (6 items), social function domain (4 items) and special disease/condition domain (10 items). Each domain is scored on a five response level Likert scale of 0-4, ranging from worst (0) to best (4). The GIQLI generates a maximum total score of 144 points, with a higher score implying a better QoL. This scale reflects QoL related to gastrointestinal problems within a period of two weeks, with a mean score of 125.8 ± 13.0 (95%CI: 121.5-127.5) points in healthy subjects.

Independent survey staff were trained and assigned to obtain baseline and follow-up measurements. In the baseline evaluation, the staff introduced patients to the survey and asked them to complete the questionnaire on site in a self-reported manner within 30 min. All patients who completed the preoperative questionnaire were subsequently followed-up by correspondence using the GIQLI scale two weeks and six weeks after treatment. The survey staff reviewed the questionnaires to determine the baseline and postoperative GIQLI scores.

Demographic data and GIQLI questionnaires were collected to create a summary database using Epidate3.1 (EpiData Software, Odense, Denmark). Two independent biostatisticians were assigned to data entry. Missing data from patients lost to follow-up were treated using the data deletion method. All data were processed using SPSS version 18.0 statistical software (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical data are expressed as n (%). Demographic data were compared using the Student’s t-test or the Pearson’s χ2 test. The general linear model with Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc analysis of variance or covariance was used to compare the total GIQLI score and each subdomain score between the two treatment groups at the baseline, as well as at the follow-up time-points. A P value of < 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance.

Patient characteristics, which included baseline demographic data, treatment outcome and follow-up outcome, are shown in Table 1. The two treatment groups were comparable in age, sex, marital status, number of children, place of residence, educational level and employment status. Gallstones were completely eliminated in all patients (216/216; 100%). EST, however, was associated with a significantly shorter hospital stay compared with OCT (8.8 ± 6.5 d vs 13.9 ± 6.7 d; P < 0.001). Among 216 eligible patients, 191 patients (191/216; 88.4%) completed all three surveys, including 118 patients who underwent EST (118/135; 87.4%) and 73 patients who underwent OCT (73/81; 90.1%). Twenty-five patients (25/216; 11.6%) were tracked during the six-week follow-up. For EST, 13 patients were lost at the two-week follow-up (13/135; 9.6%) and another four patients (4/135; 3.0%) were lost at six weeks post-EST. Eight patients (8/81; 9.9%) were lost at the two-week follow-up for OCT. The overall and time-point-specific follow-up rates were comparable between the two treatment groups.

| EST group | OCT group | P value | |

| (n = 135) | (n = 81) | ||

| Age (yr) | 60.3 ± 12.7 | 58.4 ± 13.5 | 0.299 |

| Sex (M/F) | 70/65 | 44/37 | 0.725 |

| Married | 126 (93.3) | 77 (95.1) | 0.771 |

| Childless | 12 (8.9) | 6 (7.4) | 0.703 |

| Local resident | 66 (48.9) | 49 (60.5) | 0.798 |

| Educational level | 0.050 | ||

| Primary school | 42 (31.1) | 26 (32.1) | |

| Secondary school | 44 (32.6) | 27 (33.3) | |

| High school | 24 (17.8) | 14 (17.3) | |

| College and above | 25 (18.5) | 14 (17.3) | |

| Employment status | 0.195 | ||

| Employed | 36 (26.7) | 27 (33.3) | |

| Retired | 74 (54.8) | 46 (56.8) | |

| Unemployed | 25 (18.5) | 8 (9.9) | |

| Baseline GIQLI score | 103.0 ± 15.4 | 99.7 ± 10.2 | 0.091 |

| Gallstone elimination | 135/135 (100.0) | 81/81 (100.0) | 1.000 |

| Days of hospital stay (d) | 8.8 ± 6.5 | 13.9 ± 6.7 | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up rate at | 0.662 | ||

| 2 wk | 122 (90.4) | 73 (90.1) | 1.000 |

| 6 wk | 118 (96.7) | 73 (100.0) | 0.300 |

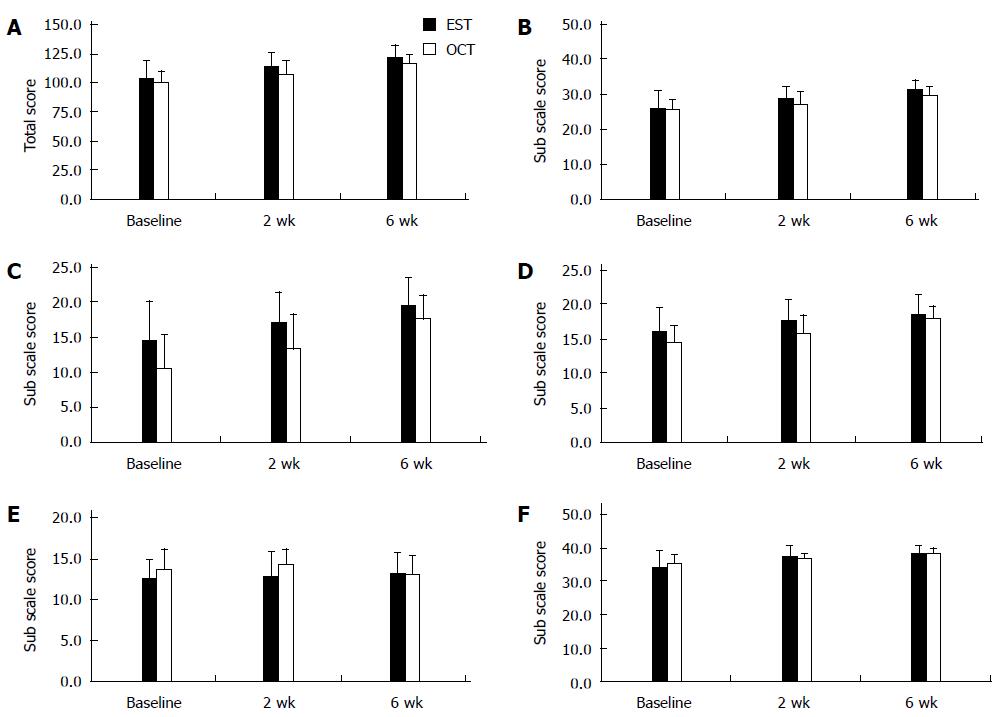

The EST group exhibited a significantly lower total GIQLI score at baseline compared with healthy subjects (103.0 ± 15.4, 59-137). At the follow-up visit two weeks post-EST, the total GIQLI score showed a significant improvement (113.4 ± 12.0, 76-134) compared with the baseline (P < 0.001). The total GIQLI score continued to increase (120.7 ± 10.6, 71-136) until the follow-up visit at six weeks post-EST compared with the baseline (P < 0.001) or the follow-up visit at two weeks (P < 0.001), and approached the lower limit (121.5) of the healthy subjects (Figure 1A).

Like the EST group, the OCT group also exhibited a significantly lower total GIQLI score at baseline as compared with healthy subjects (99.7 ± 10.2, 77-121). At the follow-up visit two weeks after the OCT procedure, the total GIQLI score showed a significant improvement (107.2 ± 11.2, 88-127) compared with the baseline (P < 0.001). The total GIQLI score continued to increase (116.9 ± 7.5, 104-130) until the follow-up visit at 6 wk post-OCT compared with the baseline (P < 0.001) or the follow-up visit at two weeks (P < 0.001), though it remained significantly lower than the lower limit for healthy subjects (P < 0.001) (Figure 1A).

Out of five domains, scores from the self-reported symptom, physical function, mental/emotional function and special disease/condition domains all continuously exhibited significant increases throughout the follow-up period of six weeks (all Ps < 0.001) (Figure 1B-D, F). However, in both groups, the social function domain score did not change throughout the follow-up period (Figure 1E).

The total GIQLI score was comparable between the two treatment groups at baseline (EST vs OCT: 103.0 ± 15.4 vs 99.7 ± 10.2). The total GIQLI scores, however, were significantly higher in the EST group compared with the OCT group at two weeks (113.4 ± 12.0 vs 107.2 ± 11.2; P < 0.001) and at six weeks (120.7 ± 10.6 vs 116.9 ± 7.5; P < 0.05) following treatment (Figure 1A).

The two treatment groups were comparable in their self-reported symptom domain scores at baseline (EST vs OCT: 25.7 ± 5.3 vs 25.6 ± 2.8). However, the self-reported symptom domain scores were significantly higher in the EST group than in the OCT group at two weeks (28.8 ± 3.2 vs 27.0 ± 3.5; P < 0.001) and six weeks (31.3 ± 2.8 vs 29.5 ± 2.8; P < 0.001) following treatment (Figure 1B).

The EST group had a significantly higher physical function domain score than the OCT group at baseline (14.4 ± 5.6 vs 10.6 ± 4.8; P < 0.001). Moreover, the physical function domain scores remained significantly higher in the EST group than those in the OCT group at two weeks (16.9 ± 4.4 vs 13.3 ± 4.9; P < 0.001) and six weeks (31.3 ± 2.8 vs 29.5 ± 2.8; P < 0.05) following the treatment (Figure 1C).

The EST group had a significantly higher mental/emotional function domain score than the OCT group at baseline (16.0 ± 3.5 vs 14.6 ± 2.3; P < 0.05). Additionally, the mental/emotional function domain score remained significantly higher in the EST group compared with the OCT group at two weeks (17.7 ± 3.1 vs 15.8 ± 2.5; P < 0.001) following treatment, though it was comparable between the two treatment groups at six weeks (18.6 ± 2.8 vs 17.9 ± 1.9) (Figure 1D).

It is important to note that the EST group had a significantly lower social function domain score than the OCT group at baseline (12.6 ± 2.4 vs 13.8 ± 2.3; P < 0.001). Additionally, the social function domain score remained significantly lower in the EST group compared with the OCT group at two weeks (12.9 ± 2.9 vs 14.4 ± 1.7; P < 0.001) following treatment, but was comparable between the two treatment groups at six weeks (13.0 ± 2.6 vs 13.5 ± 2.2) (Figure 1E).

The two treatment groups were comparable in the special disease/condition domain score (34.3 ± 4.9 vs 35.3 ± 2.6). Moreover, the special disease/condition domain score remained comparable between the two treatment groups at two weeks (37.2 ± 3.4 vs 36.8 ± 1.8) and six weeks (38.6 ± 2.0 vs 38.6 ± 1.2) following treatment (Figure 1F).

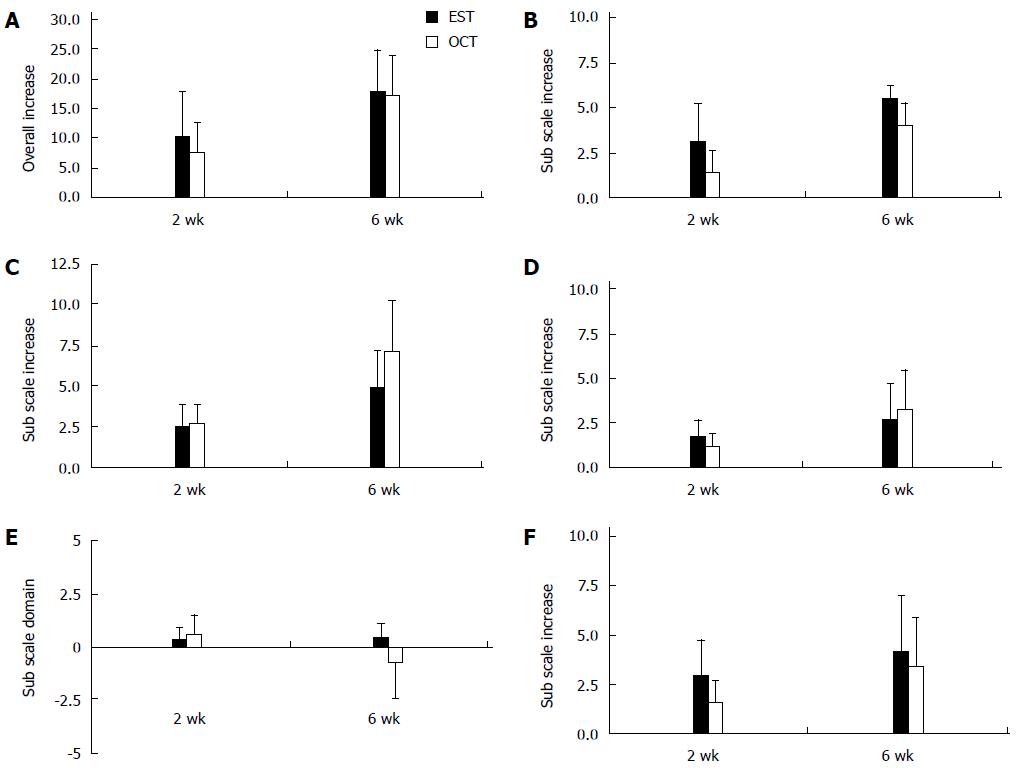

Two weeks following treatment, the overall improvement in GIQLI scores from baseline values was significantly higher in the EST group than in the OCT group (10.4 ± 7.3 vs 7.5 ± 5.2; P < 0.05) (Figure 2A). The improvements in each subscale score were significantly higher in the EST group than those in the OCT group for the self-reported symptom domain (3.1 ± 2.1 vs 1.4 ± 1.2; P < 0.001) (Figure 2B), mental/emotional function score (1.7 ± 0.9 vs 1.2 ± 0.7; P < 0.001) (Figure 2D) and special disease/condition domain (2.9 ± 1.8 vs 1.6 ± 1.1; P < 0.001) (Figure 2F). The social function domain score was significantly lower in the EST group than in the OCT group (0.3 ± 0.6 vs 0.6 ± 0.9; P < 0.05) (Figure 2E) while the physical function domain score was comparable between the two treatment groups (2.5 ± 1.3 vs 2.7 ± 1.2) (Figure 2C).

At six weeks post-treatment, the overall improvement in the GIQLI score from baseline values was comparable between the two treatment groups (17.7 ± 7.2 vs 17.2 ± 6.6) (Figure 2A). Improvement was significantly higher in the EST group compared to the OCT group for the self-reported symptom domain score (5.5 ± 2.4 vs 4.0 ± 2.2; P < 0.001) (Figure 2B) and social function domain (0.4 ± 0.7 vs -0.7 ± 1.8; P < 0.001) (Figure 2E). The physical function domain score was significantly lower in the EST group than in the OCT group (4.9 ± 2.2 vs 7.1 ± 3.1; P < 0.001) (Figure 2C). Improvements in subscale scores, however, remained comparable between the two treatment groups for the mental/emotional function domain (2.6 ± 2.0 vs 3.2 ± 2.2) (Figure 2D) and the special disease/condition domain (4.2 ± 2.8 vs 3.4 ± 2.5) (Figure 2F).

From two to six weeks following the treatments, the overall improvements in the GIQLI scores in the EST group were significantly lower than in the OCT group (7.3 ± 4.8 vs 9.7 ± 5.2; P < 0.05). The improvements in each subscale score were significantly lower in the EST group than those in the OCT group for the physical function domain (2.4 ± 1.3 vs 4.4 ± 2.2; P < 0.001), mental/emotional function score (0.9 ± 0.7 vs 2.1 ± 1.3; P < 0.001) and special disease/condition domain (1.4 ± 1.1 vs 1.8 ± 1.2; P < 0.05). Improvement in the social function domain, however, was significantly higher in the EST group than in the OCT group (0.1 ± 0.8 vs -1.3 ± 1.6; P < 0.001). Improvement in the self-reported symptom domain between the two groups was comparable (2.4 ± 1.1 vs 2.5 ± 1.2).

EST with ERCP for the removal of gallstones from the CBD is generally accepted in current practice as a safe and effective endoscopic modality[13]. EST provides patients with a rapid post-operative recovery because it is minimally invasive. This technique, however, is also subject to technical complications, such as sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, post-ERCP pancreatitis and residual gallstones[16]. The risk for these complications can be minimized by careful patient selection and by promoting the values of this surgical technique in more experienced endoscopic centers. However, the improvement in health-related QoL for choledocholithiasis patients remains unevaluated in the current literature for either classical OCT or minimally invasive EST. The present study is the first to report the benefits of EST and OCT on gastrointestinal QoL in a prospective comparative design. The GIQLI has been shown to be an effective and specific survey tool to measure the overall physical, mental and social well-being in patients with complicated gastrointestinal disorders[23]. The current results show that both techniques increased the total GIQLI score in choledocholithiasis patients throughout the six-week follow-up period. EST, compared with OCT, was consistently associated with higher self-reported symptom and physical function domain scores throughout the follow-up period. This is probably because EST is even less invasive than laparoscopic CBD exploration[24]. Therefore, following EST, choledocholithiasis patients undergo a more rapid post-operative recovery in terms of symptoms and physical well-being.

The EST group exhibited a higher mental/emotional score than the OCT group at the two-week time-point, whereas the two treatment groups were similar at the later time-point. This suggests that EST contributes favorably to the mental well-being of choledocholithiasis patients in the short term. However, this additional benefit was reduced in the mid-term as the gallstone-associated illness was eliminated similarly between the two treatment groups. In contrast, OCT, seemed to be more beneficial for improvement in social function score at the earlier time-point. It is likely that a prolonged hospital stay offers patients more access to medical care and family support. These factors may help improve patient social function in the short term. This additional benefit of OCT on social function, however, was weakened in the mid-term. It is not surprising that the two treatment groups remained consistently comparable in the special disease/condition domain score, as the two techniques are believed to be equally effective and safe if appropriately indicated[25].

To differentiate the short-term and mid-term effects of both techniques on overall and domain-specific improvements, the improvement from the baseline at two weeks was compared with improvement from week two to week six. Generally, EST was associated with a significantly higher improvement from the baseline at two weeks, but not at six weeks, compared with OCT. This suggests that EST was more favorable for post-operative recovery and an increase in QoL for choledocholithiasis patients over the short term.

This study may have some limitations. First, the patients were not randomly assigned to either treatment but were allowed to choose which treatment they received. Second, neither the investigators nor the patients were blinded to the treatment modality, and patients scheduled for EST were well informed of the minimal invasiveness of the procedure. Third, the patients were only followed for six weeks and predominantly by correspondence. The long-term effect of either treatment on choledocholithiasis patient gastrointestinal QoL remains unknown.

In conclusion, EST is associated with a better overall gastrointestinal QoL in choledocholithiasis patients compared with OCT. Furthermore, EST contributes favorably to the overall improvement in patients’ well-being over the short term, especially in terms of self-reported symptoms, physical function and mental well-being. These findings need to be further validated in large randomized controlled trials.

The Chinese population is prone to choledocholithiasis, which accounts for 18% of gallstone cases. Endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) and open choledochotomy (OCT) are two common therapeutic modalities for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. OCT is a classic surgical technique, which is subject to a high morbidity and mortality rate (1%-2%), as well as a heavy healthcare burden. EST allows for the minimally invasive removal of gallstones and shows rapid postoperative recovery. However, the superiority in general clinical variables does not necessarily indicate that EST is associated with a favorable treatment outcome compared with OCT.

Health-related quality of life (QoL) is a comprehensive measure evaluating the overall well-being of a subject in physical, mental and social aspects. This measure has been used extensively to optimize treatment algorithms, especially in chronic medical conditions like choledocholithiasis.

Whether EST contributes to a better health-related QoL improvement in patients undergoing cholelithotomy compared with OCT has not been well evaluated. Therefore, the authors performed a prospective comparative study to determine the improvement in health-related QoL in choledocholithiasis patients following either classic OCT or minimally invasive EST.

The study results suggest that EST, compared with OCT, is associated with a better overall gastrointestinal QoL in choledocholithiasis patients at two and six weeks post-operation. However, these findings need to be further validated with large randomized controlled trials.

EST is a minimally invasive surgical technique that allows for the removal of gallstones by inserting a sphincterotome through an endoscope, often following endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, for incision into Oddi’s sphincter or Vater’s ampulla.

OCT is the classical surgical technique that allows for the removal of gallstones by an incision into the common bile duct by laparotomy.

QoL is a generic concept reflecting the overall condition of human life with respect to the modification and enhancement of life attributes (e.g., physical, mental and social environment).

This is a well-designed pilot study in which the authors evaluated the improvement in gastrointestinal QoL in choledocholithiasis patients following EST or OCT treatment. The results are clinically relevant and suggest that EST, compared with, is associated with a better overall gastrointestinal QoL in choledocholithiasis patients.

P- Reviewer: Yao A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ding YB, Deng B, Liu XN, Wu J, Xiao WM, Wang YZ, Ma JM, Li Q, Ju ZS. Synchronous vs sequential laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholecystocholedocholithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2080-2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sun H, Tang H, Jiang S, Zeng L, Chen EQ, Zhou TY, Wang YJ. Gender and metabolic differences of gallstone diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1886-1891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chang YR, Jang JY, Kwon W, Park JW, Kang MJ, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yun YB, Kim SW. Changes in demographic features of gallstone disease: 30 years of surgically treated patients. Gut Liver. 2013;7:719-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pitt HA. Role of open choledochotomy in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Am J Surg. 1993;165:483-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hanif F, Ahmed Z, Samie MA, Nassar AH. Laparoscopic transcystic bile duct exploration: the treatment of first choice for common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1552-1556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ambreen M, Shaikh AR, Jamal A, Qureshi JN, Dalwani AG, Memon MM. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after open choledochotomy. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wu X, Yang Y, Dong P, Gu J, Lu J, Li M, Mu J, Wu W, Yang J, Zhang L. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage in laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:909-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhu QD, Tao CL, Zhou MT, Yu ZP, Shi HQ, Zhang QY. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after common bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kageoka M, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Nagata K, Ohata A, Noda Y, Miwa I, Ikeya K. Long-term prognosis of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:170-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tandan M, Reddy DN. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for pancreatic and large common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4365-4371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Lee JH, Kim HW, Kang DH, Choi CW, Park SB, Kim SH, Jeon UB. Usefulness of percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotomy for removal of difficult common bile duct stones. Clin Endosc. 2013;46:65-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Atar E, Neiman C, Ram E, Almog M, Gadiel I, Belenky A. Percutaneous trans-papillary elimination of common bile duct stones using an existing gallbladder drain for access. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:354-358. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bignell M, Dearing M, Hindmarsh A, Rhodes M. ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES): a safe and definitive management of gallstone pancreatitis with the gallbladder left in situ. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:2205-2210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wojtun S, Gil J, Gietka W, Gil M. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis: a prospective single-center study on the short-term and long-term treatment results in 483 patients. Endoscopy. 1997;29:258-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Follow-up of more than 10 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in young patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:917-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Costamagna G, Tringali A, Shah SK, Mutignani M, Zuccalà G, Perri V. Long-term follow-up of patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis, and risk factors for recurrence. Endoscopy. 2002;34:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hsueh LN, Shi HY, Wang TF, Chang CY, Lee KT. Health-related quality of life in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:280-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Poulose BK, Speroff T, Holzman MD. Optimizing choledocholithiasis management: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:43-48; discussion 49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rogers SJ, Cello JP, Horn JK, Siperstein AE, Schecter WP, Campbell AR, Mackersie RC, Rodas A, Kreuwel HT, Harris HW. Prospective randomized trial of LC+LCBDE vs ERCP/S+LC for common bile duct stone disease. Arch Surg. 2010;145:28-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Leung D, Yetasook AK, Carbray J, Butt Z, Hoeger Y, Denham W, Barrera E, Ujiki MB. Single-incision surgery has higher cost with equivalent pain and quality-of-life scores compared with multiple-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective randomized blinded comparison. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:702-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Xin Y, Zhu X, Wei Q, Cai X, Wang X, Huang D. Comparison of quality of life between two biliary drainage procedures in laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:331-333. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Lien HH, Huang CC, Wang PC, Chen YH, Huang CS, Lin TL, Tsai MC. Validation assessment of the Chinese (Taiwan) version of the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index for patients with symptomatic gallstone disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:429-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shi HY, Lee HH, Chiu CC, Chiu HC, Uen YH, Lee KT. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important differences after cholecystectomy: GIQLI versus SF-36. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1275-1282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | ElGeidie AA, ElShobary MM, Naeem YM. Laparoscopic exploration versus intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones: a prospective randomized trial. Dig Surg. 2011;28:424-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yi SY. Recurrence of biliary symptoms after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in patients with gall bladder stones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:661-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |