Published online Jul 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8221

Revised: March 16, 2014

Accepted: April 15, 2014

Published online: July 7, 2014

Processing time: 158 Days and 4 Hours

AIM: To compare outcomes using the novel portable endoscopy with that of nasogastric (NG) aspiration in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.

METHODS: Patients who underwent NG aspiration for the evaluation of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding were eligible for the study. After NG aspiration, we performed the portable endoscopy to identify bleeding evidence in the UGI tract. Then, all patients underwent conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopy as the gold-standard test. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the portable endoscopy for confirming UGI bleeding were compared with those of NG aspiration.

RESULTS: In total, 129 patients who had GI bleeding signs or symptoms were included in the study (age 64.46 ± 13.79, 91 males). The UGI tract (esophagus, stomach, and duodenum) was the most common site of bleeding (81, 62.8%) and the cause of bleeding was not identified in 12 patients (9.3%). Specificity for identifying UGI bleeding was higher with the portable endoscopy than NG aspiration (85.4% vs 68.8%, P = 0.008) while accuracy was comparable. The accuracy of the portable endoscopy was significantly higher than that of NG in the subgroup analysis of patients with esophageal bleeding (88.2% vs 75%, P = 0.004). Food material could be detected more readily by the portable endoscopy than NG tube aspiration (20.9% vs 9.3%, P = 0.014). No serious adverse effect was observed during the portable endoscopy.

CONCLUSION: The portable endoscopy was not superior to NG aspiration for confirming UGI bleeding site. However, this novel portable endoscopy device might provide a benefit over NG aspiration in patients with esophageal bleeding.

Core tip: Although nasogastric (NG) tube aspiration is recommended for the potential benefit of risk stratification in upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding, its clinical usefulness is still debatable. Recently, a novel bedside portable endoscopy device (EG scan, IntroMedic Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) has been developed to evaluate the esophagogastroduodenal area with high convenience and notable accessibility compared with conventional endoscopy. As far as we know, this is the first study to evaluate the clinical outcomes of this device compared with NG tube aspiration in UGI bleeding identification. We found that EG scan might offer benefits over NG aspiration in patients with esophageal bleeding.

- Citation: Choi JH, Choi JH, Lee YJ, Lee HK, Choi WY, Kim ES, Park KS, Cho KB, Jang BK, Chung WJ, Hwang JS. Comparison of a novel bedside portable endoscopy device with nasogastric aspiration for identifying upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(25): 8221-8228

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i25/8221.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i25.8221

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding is a common, important emergency situation with an estimated incidence of roughly 100 per 100000 adults[1]. Although advances in medical and endoscopic treatment have had positive effects on the outcomes of UGI bleeding, mortality still remains high, up to 10%[2-5]. A recently reported international consensus on UGI bleeding emphasized the importance of the early risk stratification for rebleeding and mortality[6]. It is recommended to place a nasogastric (NG) tube in patients with UGI bleeding for risk assessment because the findings may have prognostic value[6]. However, the usefulness of NG tube placement in identifying UGI sources of bleeding has not been clarified due to its low sensitivity (42%-84%) and poor negative likelihood ratio (0.62-0.20)[7-9].

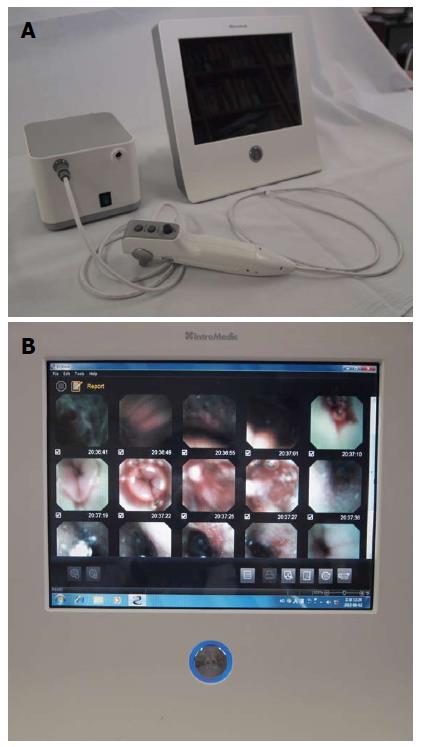

A novel bedside portable endoscopy device (EG scan, IntroMedic Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) has been developed to evaluate the esophagogastroduodenal area with high convenience and notable accessibility compared with conventional endoscopy[10]. The EG scan comprises four parts: an optical probe, a control handle, a processor that generates air, and a display monitor (Figure 1). The diameter of the probe tip is 6 mm, similar to that of a 16-French NG tube and the shaft of probe is much thinner, with a diameter of 3.6 mm (Figure 2). The probe can reach to the stomach through the nose as easily as an NG tube. The real-time imaging view is visualized via the display monitor. The optical probe tip can be bent 60° upwards or downwards, but not to the right or left side. There has been no previous reported study of the efficacy of this novel endoscopy device compared with that of the NG tube in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of this novel bedside portable endoscopy device by comparing the outcome of this scope with that of the NG tube for the identification of the source of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Adult patients (older than 18 years) presenting with symptoms or signs of gastrointestinal bleeding, including melena, hematemesis, hematochezia, and acute-onset anemia, at a tertiary hospital between January 2012 and September 2012 were eligible for this prospective study. Exclusion criteria included (1) critical vital sign instability; (2) inability to get the NG tube or EG scan device through the nostrils; (3) refusal to undergo the procedure/failure to give consent; and (4) no final esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) evaluation (patients who refuse to undergo EGD for any reason). Patients with hemodynamic instability received crystalloid solutions and blood transfusions. First, patients suspicious for active gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding who visited the emergency room received NG tube insertion and aspiration with or without lavage to confirm active UGI bleeding according to the International Consensus Recommendations for patients with UGI bleeding[6]. Then, the EG scan device was inserted within 12 h from NG tube insertion to identify the focus of the UGI bleeding. The scope was inserted through the nose with lubricant jelly and no sedatives or antispasmodics were used during the procedures. The EG scan was performed by three endoscopists with at least 1000 cases of EGD experience (ESK, YJL, and KSP) or three medical personnel with no previous endoscopy experience (JHC, WYC, and JHC) after brief instruction on how to use the EG scan probe. Non-endoscopists learned about luminal lesions, such as varices, ulcers, and erosions, by reviewing endoscopic images before the EG scan. Doctors who performed EG scan did not know the results of NG tube aspiration. Thereafter, all patients underwent EGD as the gold-standard test for the final diagnosis of UGI bleeding.

Informed consent was obtained from patients and the study protocol was approved by the Keimyung University Institutional Review Board. The study was registered on the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP KCT0000298).

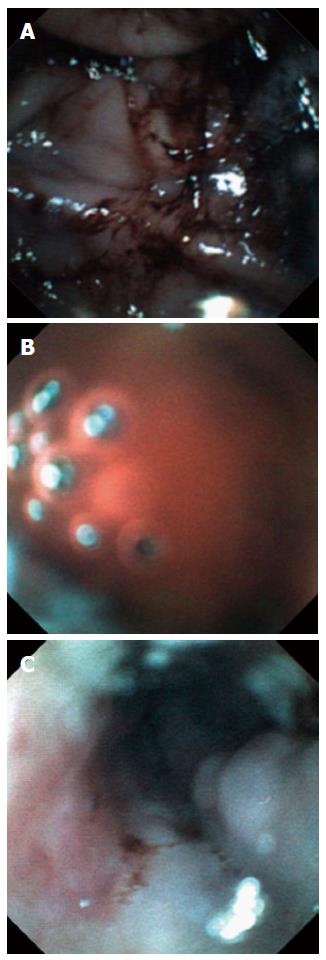

Dark, coffee ground- or bright red-colored blood seen at NG aspiration was defined as a positive sign of UGI bleeding. During the EG scan procedure, a directly visualized coffee ground-colored blood clot or bright red blood was recorded as a positive sign of UGI bleeding (Figure 3). Additionally, luminal lesions, such as esophageal varices, ulcers or erosions, were evaluated during the EG scan (Figure 3). We attempted to estimate additional findings, including food material, at each procedure. Primary outcome measures were (1) comparison of the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the EG scan in identifying UGI bleeding with NG tube insertion; and (2) the rate of adverse event of the EG scan procedure.

Sensitivity was the proportion of subjects with UGI bleeding who had a positive test result, and specificity was the proportion of individuals without UGI bleeding who had a negative test result. Accuracy was the proportion of all cases correctly identified by the test. Differences in these categorical variables with matched pairs of subjects were examined with McNemar’s test. For comparison of continuous variables, Student’s t-test was used and the results are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD).

The sample size was calculated on the assumption that accuracy of the EG scan for identifying UGI bleeding would be 60%, while that of NG tube aspiration would be 40%. With a two-tailed test of α = 0.05 and 1-β = 0.80, 117 patients were required. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS software (ver. 14.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

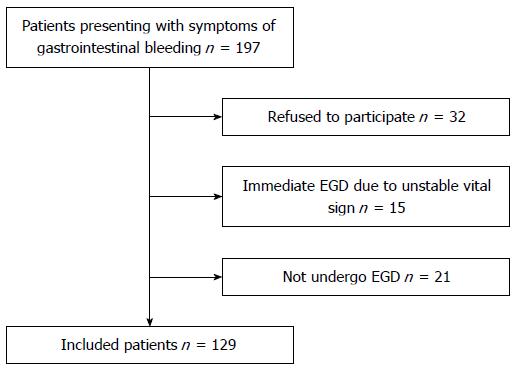

Among 197 patients with signs or symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding, 129 were finally included in the study (mean age 64.46 ± 13.79 years, males 70.5%). In total, 68 subjects (34.5%) were excluded for various reasons: 32 refused to participate, 15 skipped the EG scan for an immediate therapeutic endoscopy due to unstable vital signs, and 21 did not undergo final EGD (Figure 4). Baseline characteristics of patients are described in Table 1. The most common co-morbidity was high blood pressure (48, 37.2%), followed by liver cirrhosis (39, 30.2%). Initial systolic blood pressure was 119.52 ± 25.67 mmHg and pulse rate was 85.31 ± 15.78/min. Initial hemoglobin was 9.55 ± 2.62 g/dL. The most common bleeding-related symptom was melena (46, 35.7%), followed by hematemesis (43, 33.3%) and hematochezia (28, 21.7%). The major non-bleeding-related symptom was dizziness (14, 10.9%).

| Age, mean ± SD, yr | 64.46 ± 13.79 (n =129) |

| Gender, Male | 91 (70.5) |

| Co-morbidities | |

| Hypertension | 48 (37.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (25.6) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 17 (13.2) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 39 (30.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 (10.9) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 22 (17.1) |

| Malignancy | 25 (19.4) |

| Initial vital sign | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 119.52 ± 25.67 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 72.33 ± 17.53 |

| Pulse rate, mean ± SD | 85.31 ± 15.78 |

| Initial hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.55 ± 2.62 |

| Bleeding related signs or symptoms | |

| Melena | 46 (35.7) |

| Hematemesis | 43 (33.3) |

| Hematochezia | 28 (21.7) |

| Anemia | 12 (9.3) |

| Non-bleeding related signs or symptoms | |

| Dizziness | 14 (10.9) |

| Epigastric pain | 13 (10.1) |

| Syncope | 2 (1.6) |

| Dyspnea | 2 (1.6) |

EGD confirmed the UGI tract as the source of bleeding in 81 (62.8%) cases (Table 2). Among them, esophageal varices, gastric ulcers and varices, and duodenal ulcers were the major causes of bleeding. The cause of bleeding in 12 (9.3%) was not identified. The mean time interval (min) from NG aspiration to EG scan was 129.5 ± 190.5. The mean time interval (h) from EG scan to EGD was 7.3 ± 7.6. The mean procedure time (min) of the EG scan was 5.49 ± 2.33. The probe was inserted into the stomach in all cases except one while duodenal insertion was possible only in four cases. In six patients, examiners reported that they were not sure whether the probe was inserted into the duodenum due to poor visualization. There was no significant difference in the positive rate for bleeding (detection of blood) between the EG scan and NG tube aspiration (45.7% vs 58.1%, P > 0.05). Food material could be detected more readily by the EG scan than NG tube aspiration (20.9% vs 9.3%, P = 0.014). The EG scan provided additional findings of luminal lesions, including varices, ulcers, or erosions. The EG scan showed esophageal lesions in 41 (31.8%) patients (26 varices, 6 ulcers, and 15 erosions; 6 patients had multiple lesions). However, stomach lesions were found only in nine (7%) patients (three ulcers and six erosions), and the EG scan failed to detect any duodenal lesion. Nasal pain and nausea were more frequently observed with the EG scan than NG tube aspiration while epistaxis was more common with NG tube aspiration. Nonetheless, there was no serious adverse effect during or after EG scan (Table 3).

| Patients n =129 | |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 81 (62.8) |

| Esophagus | 20 (15.5) |

| Esophageal varices | 17 (13.1) |

| Esophageal ulcers | 3 (2.3) |

| Stomach | 53 (41.1) |

| Gastric ulcers | 35 (27.1) |

| Gastric varices | 8 (6.2) |

| Hemorrhagic gastritis | 4 (3.2) |

| Mallory-Weiss syndrome | 3 (2.3) |

| Cancer | 2 (1.5) |

| Angiodysplasia | 1 (0.8) |

| Duodenum | 8 (6.2) |

| Duodenal ulcers | 7 (5.4) |

| Angiodysplasia | 1 (0.8) |

| Non upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 36 (27.9) |

| Small bowel bleeding | 8 (6.2) |

| Colorectum | 23 (17.8) |

| Colitis | 9 (6.9) |

| Ulcers | 7 (5.4) |

| Cancers | 2 (1.5) |

| Diverticulum | 2 (1.5) |

| Hemorrhoid | 1 (0.8) |

| Rectal varices | 1 (0.8) |

| Radiation colitis | 1 (0.8) |

| Others | 5 (4) |

| Hemoptysis | 4 (3.2) |

| Nasal bleeding | 1 (0.8) |

| No definite focus of bleeding | 12 (9.3) |

| Patients n = 129 | |||

| EG scan | NG tube aspiration | P value | |

| Procedure time, mean ± SD, min | 5.49 ± 2.33 | ||

| Examiner | |||

| Endoscopist | 24 (18.6) | 0 | |

| Non-endoscopist | 105 (81.4) | 129 (100) | |

| Insertion to stomach | 128 (99.2) | 129 (100) | |

| Insertion to duodenum | 4 (3.1) | ||

| Main findings | |||

| Blood | 59 (45.7) | 75 (58.1) | 0.061 |

| Food material | 27 (20.9) | 12 (9.3) | 0.014 |

| Esophageal lesions1 | 41 (31.8) | ||

| Stomach lesions1 | 9 (7.0) | ||

| Duodenal lesions | 0 | ||

| Adverse effects | |||

| Nasal pain | 60 (46.5) | 40 (31) | 0.015 |

| Nausea | 26 (20.1) | 5 (3.9) | < 0.001 |

| Epistaxis | 11 (8.5) | 28 (21.7) | 0.005 |

| Cough | 9 (6.9) | 11 (8.5) | 0.817 |

| Others | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.6) | 1.000 |

Overall (n = 129), accuracy and sensitivity of the EG scan for UGI bleeding identification was not different from those of NG tube aspiration, whereas the specificity of the EG scan was significantly higher than that of NG aspiration (85.4% vs 68.8%, P = 0.008). However, when we focused on bleeding in the esophageal area (n = 68), the accuracy of the EG scan became significantly better than that of the NG tube (88.2% vs 75%, P = 0.004; Table 4).

| Overall n = 129 | Esophagus n = 68 | |||||

| EG scan | NG tube | P value | EG scan | NG tube | P value | |

| Sensitivity | 64.2 (52/81) | 74.1 (60/81) | > 0.05 | 95 (19/20) | 90 (18/20) | > 0.05 |

| Specificity | 85.4 (41/48) | 68.8 (33/48) | 0.008 | 85.4 (41/48) | 68.8 (33/48) | 0.008 |

| Accuracy | 72.1 (93/129) | 72.1 (93/129) | > 0.05 | 88.2 (60/68) | 75 (51/68) | 0.004 |

Most cases of the EG scan (105, 81.4%) were performed by non-endoscopists while experts conducted the EG scan in 24 cases (18.6%). The procedure time for endoscopists was shorter than that for non-endoscopists (4.33 ± 1.76 vs 5.75 ± 2.36 min; P = 0.001). However, the experience of the endoscopist did not make any difference in other procedural outcomes including rate of insertion to duodenum, main findings, and accuracy for UGI bleeding identification (Table 5).

| Endoscopists n = 24 | Non-endoscopists n = 105 | P value | |

| Procedure time, mean ± SD, min | 4.33 ± 1.76 | 5.75 ± 2.36 | 0.001 |

| Insertion to duodenum | 1 (4.2) | 3 (2.9) | 0.657 |

| Main findings | |||

| Blood | 10 (41.7) | 49 (46.7) | 0.821 |

| Esophageal lesions | 6 (25) | 35 (33.3) | 0.478 |

| Stomach lesions | 2 (8.3) | 7 (6.7) | 0.673 |

| Accuracy for UGI bleeding | 16 (66.7) | 77 (73.3) | 0.614 |

For patients suspected of having UGI bleeding, NG aspiration can be useful for determining the management strategy by localizing the source of bleeding[11-13]. Additionally, this practice may enhance risk stratification. For example, patients with a bloody aspirate are more likely to have active bleeding, high-risk lesions, and higher rates of recurrent hemorrhage, leading to a greater mortality[7,14,15]. Thus, the consensus guidelines recommend placing a NG tube for pre-endoscopic evaluation[6]. However, it is still uncertain as to whether NG aspiration improves clinical outcomes in the management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. A retrospective observational study showed that NG aspiration did not lessen mortality or shorten hospital length of stay suggesting that this practice might be unnecessary in the management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding[16,17]. Furthermore, relatively high false negative rates (10%-18%) in NG aspiration may hinder effective management[18].

This prospective study showed that the EG scan, a novel portable bedside endoscopy device, had better specificity than NG tube aspiration for the identification of bleeding while the overall accuracy was not different between the two procedures. Unexpectedly, the overall sensitivity of the EG scan appeared to be lower than that of NG aspiration (64.2% vs 74.1%, P > 0.05). In the cases of bleeding in the esophageal area, however, accuracy of the EG scan was superior to that of NG aspiration and the sensitivity increased to 95%. The unexpectedly lower overall sensitivity of the EG scan compared with that of NG aspiration was disappointing in the present study. With this low sensitivity, a negative finding with the EG scan in a patient with suspected UGI bleeding cannot reassure the endoscopist to wait and delay EGD. For screening purposes, a test should have characteristics of high sensitivity or a low false negative value. There are several potential explanations for the low sensitivity of the EG scan. First, the visual imaging quality of the EG scan may be unsatisfactory. As the camera system of this device has been developed technically similar to that of capsule endoscopy (MiroCam, IntroMedic, Seoul, Korea)[10,19], its visibility is substantially limited especially for roomy spaces, such as stomach area, while it can show better quality images in narrower areas, such as the esophagus or small bowel. Our result showing higher sensitivity and accuracy of the EG scan in the esophageal area supports this explanation. Additionally, there is no way to wash the cover glass of the camera, which may cause poor visibility of the EG scan[10]. Second, there was a time interval from NG tube aspiration to EG scan (mean ± SD, min, 129.5 ± 190.5). Although we thought that the time lag between NG tube aspiration and EG scan was not long enough to affect the outcomes of the EG scan, blood might be irrigated and washed away to small bowel, especially after gastric lavage through the NG tube, perhaps leading to the low sensitivity of the EG scan. When we conducted a subgroup analysis of the time intervals of less than 2 h, the sensitivity of the EG scan did increase, to 73.3% from 64.2% (data not shown).

The results of the study indicate the benefit of the EG scan in identifying esophageal lesions as a source of UGI bleeding. This may have significant clinical implications for specific situations requiring prompt recognition of an esophageal source of bleeding, such as patients with liver cirrhosis who are suspicious of acute UGI bleeding. It has been reported that esophageal varices are the cause of bleeding in only half of cirrhotic patients (53%-59%)[20,21]. Thus, it is clinically relevant to differentiate variceal bleeding from non-variceal bleeding in these patients because initial pre-endoscopic treatments are different; the former needs vasoactive agents (somatostatin, octreotide, or terlipressin)[22,23] while a high-dose proton pump inhibitor is recommended in the latter[4,6,24,25]. In our study with 39 cirrhotic patients, esophageal varices were the cause of bleeding in 17 cases (43.6%) of which 12 (88.2%) were correctly localized in the esophagus as the bleeding source by the EG scan. Further study is needed to verify this advantageous effect of EG scan in cirrhotic patients with UGI bleeding.

Compared with NG aspiration, another theoretical advantage of the EG scan would be real-time visualization of the lumen, including mucosal ulcers or erosions. However, this benefit also seemed to be limited to the esophageal area. The EG scan found 41 (31.8%) suspicious esophageal lesions, but only 9 (7%) gastric lesions. The EG scan performance was even worse for the duodenal area; it could be inserted through the pylorus in only four (3.1%) cases. These disappointing outcomes in stomach and duodenum might be attributed to the poor visualization of the EG scan, as described above.

Another potential advantage of EG scan over NG aspiration would be confirmation of food material in the stomach, which might cause aspiration pneumonia during or after an emergency EGD procedure. The detection rate of food material with the EG scan was higher than that of NG tube aspiration (20.9% vs 9.3%, P = 0.014). Therefore, when an EG scan finds food material without active bleeding evidence, it can delay an unnecessary urgent EGD, possibly resulting in avoiding the risk of aspiration pneumonia.

Our results also indicate no significant difference in the EG scan outcomes between examiners with and without endoscopy experience, except procedure time, and that it had no serious adverse effect, suggesting this practice can be performed easily and safely by medical personnel who do not have specialist endoscopy procedure skills.

There was no major adverse effect such as perforation or aspiration during and after EG scan procedure. Nasal pain and nausea were more common during EG scan than NG tube aspiration. The high rate of complaints during EG scan might be attributed to the slightly large diameters of tip of scan compared to 16 French NG tube (6 mm vs 5.3 mm). Interestingly, epistaxis was less frequently observed during EG scan. Although the cause is not clear, we hypothesize that the very thin shaft of the EG scan (3.6 mm) might reduce the proceeding force which was generated during the EG scan tip advancement. A case series study of EG scan showed that there was no epistaxis during EG scan procedures[26].

This study had a limitation that should be noted. We compared the accuracy of the EG scan and NG tube aspiration in a matched pair-wise manner in the same group of patients (NG aspiration then EG scan) rather than a head-to-head comparison in two independent groups of subjects because there might be an ethical issue if we performed the EG scan in a patient without knowing its efficacy or safety. The main reason for the delay between NG and EG scan examination was due to the time taking notification to doctors of gastroenterology division. This design of the study could presumably lead to a poor outcome of the EG scan, such as low sensitivity for detecting blood.

In conclusion, the EG scan is safe and can be as easily performed by non-endoscopists as NG aspiration. Although this novel endoscopy was not superior to NG aspiration for identifying UGI bleeding, it might offer benefits for patients where it is necessary to localize an esophageal source of bleeding. Further study is needed to confirm whether these potential advantages of the EG scan can change the clinical course of patients with acute UGI bleeding.

Although advances in medical and endoscopic treatment have had positive effects on the outcomes of upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding, mortality still remains high. It is recommended to place a nasogastric (NG) tube in patients with UGI bleeding for risk assessment because the findings may have prognostic value. However, the usefulness of NG tube placement in identifying UGI sources of bleeding has not been clarified due to its low sensitivity (42%-84%) and poor negative likelihood ratio (0.62-0.20).

A novel bedside portable endoscopy device (EG scan, IntroMedic Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) has been developed to evaluate the esophagogastroduodenal area with high convenience and notable accessibility compared with conventional endoscopy. There has been no previous reported study of the efficacy of this novel endoscopy device compared with that of the NG tube in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.

In this study, specificity for identifying UGI bleeding was higher with EG scan than NG aspiration (85.4% vs 68.8%, P = 0.008) while accuracy was comparable. The accuracy of EG scan was significantly higher than that of NG in the subgroup analysis of patients with esophageal bleeding (88.2% vs 75%, P = 0.004). Food material could be detected more readily by EG scan than NG tube aspiration (20.9% vs 9.3%, P = 0.014). No serious adverse effect was observed during the portable endoscopy.

This novel portable endoscopy device might provide a benefit over NG aspiration in patients with esophageal bleeding. Further study is needed to confirm whether these potential advantages of the EG scan can change the clinical course of patients with acute UGI bleeding.

Positive sign of UGI bleeding in NG aspiration: Dark, coffee ground- or bright red-colored blood; positive sign of UGI bleeding in the EG scan: A directly visualized coffee ground-colored blood clot or bright red blood; sensitivity: The proportion of subjects with UGI bleeding who had a positive test result; Specificity: The proportion of individuals without UGI bleeding who had a negative test result; accuracy: The proportion of all cases correctly identified by the test.

This is a very interesting paper addressing the important clinical problem of triaging upper GI bleeding. The most important advantage of this method that was applied in the manuscript is the statistically significant sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of EG scan in the esophageal lesions. In addition, the useful role of this new tool would be in identifying food in the stomach which may increase aspiration risk with sedation.

P- Reviewers: Chen Z, Engin AB, Mountifield R S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222-226. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Loperfido S, Baldo V, Piovesana E, Bellina L, Rossi K, Groppo M, Caroli A, Dal Bò N, Monica F, Fabris L. Changing trends in acute upper-GI bleeding: a population-based study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:212-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cho HS, Han DS, Ahn SB, Byun TJ, Kim TY, Eun CS, Jeon YC, Sohn JH. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Interventional Endoscopy in Bleeding Peptic Ulcer Disease according to the Timing of Endoscopy. Gut Liver. 2009;3:266-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Holster IL, Kuipers EJ. Management of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: current policies and future perspectives. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1202-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | González-González JA, Vázquez-Elizondo G, García-Compeán D, Gaytán-Torres JO, Flores-Rendón ÁR, Jáquez-Quintana JO, Garza-Galindo AA, Cárdenas-Sandoval MG, Maldonado-Garza HJ. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2011;103:196-203. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, Sinclair P. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aljebreen AM, Fallone CA, Barkun AN. Nasogastric aspirate predicts high-risk endoscopic lesions in patients with acute upper-GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:172-178. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Cappell MS. Safety and efficacy of nasogastric intubation for gastrointestinal bleeding after myocardial infarction: an analysis of 125 patients at two tertiary cardiac referral hospitals. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:2063-2070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Witting MD, Magder L, Heins AE, Mattu A, Granja CA, Baumgarten M. Usefulness and validity of diagnostic nasogastric aspiration in patients without hematemesis. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cho JH, Kim HM, Lee S, Kim YJ, Han KJ, Cho HG, Song SY. A pilot study of single-use endoscopy in screening acute gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luk GD, Bynum TE, Hendrix TR. Gastric aspiration in localization of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. JAMA. 1979;241:576-578. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Zuckerman GR, Prakash C. Acute lower intestinal bleeding: part I: clinical presentation and diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:606-617. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cello JP. Diagnosis and management of lower gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage. West J Med. 1985;143:80-87. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Adamopoulos AB, Baibas NM, Efstathiou SP, Tsioulos DI, Mitromaras AG, Tsami AA, Mountokalakis TD. Differentiation between patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding who need early urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and those who do not. A prospective study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:381-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Perng CL, Lin HJ, Chen CJ, Lee FY, Lee SD, Lee CH. Characteristics of patients with bleeding peptic ulcer requiring emergency endoscopy and aggressive treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1811-1814. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Huang ES, Karsan S, Kanwal F, Singh I, Makhani M, Spiegel BM. Impact of nasogastric lavage on outcomes in acute GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:971-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pallin DJ, Saltzman JR. Is nasogastric tube lavage in patients with acute upper GI bleeding indicated or antiquated? Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:981-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gilbert DA, Silverstein FE, Tedesco FJ, Buenger NK, Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. III. Endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:94-102. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bang S, Park JY, Jeong S, Kim YH, Shim HB, Kim TS, Lee DH, Song SY. First clinical trial of the “MiRo” capsule endoscope by using a novel transmission technology: electric-field propagation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | del Olmo JA, Peña A, Serra MA, Wassel AH, Benages A, Rodrigo JM. Predictors of morbidity and mortality after the first episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;32:19-24. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lecleire S, Di Fiore F, Merle V, Hervé S, Duhamel C, Rudelli A, Nousbaum JB, Amouretti M, Dupas JL, Gouerou H. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis and in noncirrhotic patients: epidemiology and predictive factors of mortality in a prospective multicenter population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:321-327. [PubMed] |

| 22. | de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 794] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1229] [Cited by in RCA: 1210] [Article Influence: 67.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lau JY, Leung WK, Wu JC, Chan FK, Wong VW, Chiu PW, Lee VW, Lee KK, Cheung FK, Siu P. Omeprazole before endoscopy in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1631-1640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Trawick EP, Yachimski PS. Management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage: controversies and areas of uncertainty. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1159-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chung JW, Park S, Chung MJ, Park JY, Park SW, Chung JB, Song SY. A novel disposable, transnasal esophagoscope: a pilot trial of feasibility, safety, and tolerance. Endoscopy. 2012;44:206-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |