Published online Jun 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7242

Revised: January 16, 2014

Accepted: March 6, 2014

Published online: June 21, 2014

Processing time: 220 Days and 16.5 Hours

Chronic liver diseases represent a major global health problem both for their high prevalence worldwide and, in the more advanced stages, for the limited available curative treatment options. In fact, when lesions of different etiologies chronically affect the liver, triggering the fibrogenesis mechanisms, damage has already occurred and the progression of fibrosis will have a major clinical impact entailing severe complications, expensive treatments and death in end-stage liver disease. Despite significant advances in the understanding of the mechanisms of liver fibrinogenesis, the drugs used in liver fibrosis treatment still have a limited therapeutic effect. Many drugs showing potent antifibrotic activities in vitro often exhibit only minor effects in vivo because insufficient concentrations accumulate around the target cell and adverse effects result as other non-target cells are affected. Hepatic stellate cells play a critical role in liver fibrogenesis , thus they are the target cells of antifibrotic therapy. The application of nanoparticles has emerged as a rapidly evolving area for the safe delivery of various therapeutic agents (including drugs and nucleic acid) in the treatment of various pathologies, including liver disease. In this review, we give an overview of the various nanotechnology approaches used in the treatment of liver fibrosis.

Core tip: New drugs or new drug delivery strategies to cure liver fibrosis are needed to find effective therapeutic options for this pathologic condition. Therapies based on nanotechnologies have emerged as an innovative and promising alternative to conventional therapies. This work aims to review the most recent literature about the use of nanotechnology approaches to reduce liver fibrosis.

- Citation: Giannitrapani L, Soresi M, Bondì ML, Montalto G, Cervello M. Nanotechnology applications for the therapy of liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(23): 7242-7251

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i23/7242.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7242

Chronic liver diseases (CLD) are disorders that chronically affect the liver, undermining its capacity to regenerate after injury and triggering a wound-healing response that involves a range of cell types and mediators which try to limit the injury and set in motion the fibrogenesis mechanisms. The sustained signals associated with CLD of whatever origin (infections, drugs, metabolic disorders, autoimmunity, etc.) are required for significant fibrosis to accumulate, which predisposes to the development of cirrhosis and its complications.

Liver fibrogenesis in response to a chronic infection associated with hepatitis viruses (HBV and HCV), chronic alcohol consumption, genetic abnormalities, steatohepatitis, autoimmunity, etc. is the consequence at the cellular and molecular levels of the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and their transformation into myofibroblasts which overproduce extracellular matrix, mainly type I and III collagens. Liver fibrosis may regress following specific therapeutic interventions, but no anti-fibrotic drugs are currently available in clinical practice other than those which eliminate the risk factors. Indeed, several clinical trials testing potential anti-fibrotic drugs [such as angiotensin II antagonists, interferon gamma, peroxisomal proliferator activated receptor (PPAR) gamma ligands, pirfenidone, colchicine, silymarin, polyenylphosphatidylcholine, ursodeoxycholic acid and Interleukin-10], have failed to observe either a halt in the progression of liver fibrosis or its reversal[1].

An important disadvantage of the standard therapy is that it is unable to provide a sufficient concentration of the therapeutic agent to treat liver disease and/or it leads to side effects.

Recently, therapies based on nanotechnologies have emerged as an innovative and promising alternative to conventional therapy. Nanotechnology is a rapidly growing branch of science focused on the development, manipulation and application of materials ranging in size from 10-500 nm either by scaling up from single groups of atoms or by refining or reducing bulk materials into nanoparticles (NPs). Currently, nanoparticles are being constructed with biocompatible materials and they possess great potential in delivering drugs in a more specific manner: either passively by optimizing the physicochemical properties of the drug nanocarriers (such as the size and surface properties) or actively by using tissue/cell-specific homing devices which allow the targeting of the disease site, while minimizing side-effects. Therefore, NPs can be engineered as nanoplatforms for the effective and targeted delivery of drugs, also thanks to their ability to overcome many biological, biophysical, and biomedical barriers.

In recent years, nanomedicine-based approaches have been explored for liver disease treatment. In this review, we will describe the most common NP types employed in the treatment of fibrotic liver diseases.

Therapeutic NPs are generally defined as nanostructures constituted by therapeutic drugs, peptides, proteins or nucleic acids loaded in carriers with at least one length in the nanometer range. Drugs and imaging labels which cannot achieve an effective and targeted delivery due to biological, biophysical, and biomedical barriers can be engineered as NPs. The possibility to incorporate drugs and genes into NPs through the conjugation or coating of ligands specifically binding to target cells or tissues opens a new era for delivering drugs and genes selectively to the disease site. There are several advantages to using NP delivery systems: (1) protection of the therapeutic agent, especially nucleic acid, against inactivation until it reaches the site of action; (2) feasibility of incorporation of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic agents; (3) optimization of pharmacological effectiveness (increased bioavailability of drugs); (4) reduction of toxicity and side effects of the drug; (5) reduction of drug blood level fluctuations (lower risk of ineffective or toxic concentration); (6) potential broad spectrum of administration routes (external, ophthalmic, oral and parenteral); (7) controlled drug release; and (8) active targeting due to the possibility of obtaining a greater affinity of the nanoparticle system (functionalized nanoparticle) for certain tissues. Following systemic administration, conventional NPs are opsonized by plasma proteins, recognized as foreign bodies and rapidly captured by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). The liver and the spleen are the major organs of accumulation of NPs[2,3] due to their rich blood supply and the abundance of tissue-resident phagocytic cells, therefore liver targeting by NPs may be favorable for treating liver diseases[2,3].

The uptake and distribution of NPs depend on their size: (1) NPs with a mean diameter > 400 nm are quickly captured by the RES; and (2) NPs with a diameter < 200 nm show prolonged blood circulation and a relatively low rate of RES uptake[4]. On the other hand, to reduce opsonization by blood proteins and to prolong bloodstream circulation by limiting RES uptake and reducing immunogenicity/antigenicity, biologically inert hydrophilic polymers, such as poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), have been covalently linked to the nanocarrier surface[5,6]. These types of NPs are commonly called “stealth” NPs[5,6].

Nanomedicine is referred to as the field of medicine that deals with the application of nanotechnology to address medical problems[7-9], and recently nanomedicine-based approaches have been explored for liver disease treatment.

The variety of materials that can be used to create NPs is enormous and the number of NPs used in biomedical research and drug delivery is rapidly increasing. They can be classified into two major types: inorganic and organic NPs. Here, we briefly summarize only the structure, properties and characteristics of some of the most commonly-used NPs for the treatment of liver fibrosis.

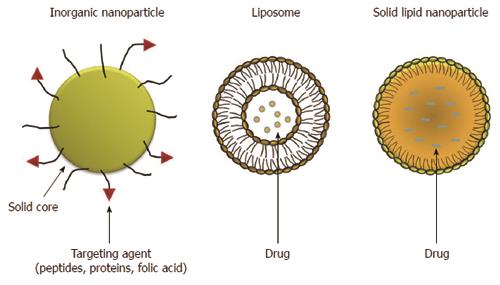

Inorganic NPs have received great attention because of their outstanding properties. Generally, inorganic nanoparticles can be defined as particles with a metal oxide (iron oxide, titanium oxide, etc.) or metal (gold and silver) central core and with a protective organic layer on the surface. The organic outer layer both protects the core from degradation and also allows the conjugation of biomolecules with reactive groups (amines and thiols) to link peptides, proteins and folic acid (Figure 1). In recent years inorganic NPs have gained significant attention due to their unique material- and size-dependent physicochemical properties, which are not possible with organic NPs. Their unique optical, magnetic and electronic properties can be tailored by controlling the composition, size, shape, and structure. In some cases, inorganic nanoparticles are attractive alternatives to organic NPs for drug delivery and imaging a specific tissue because of their physical features, such as optical and magnetic properties, in addition to their inertness, stability and easy functionalization[10-13].

Polymeric NPs, liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) form a large and well-established group of organic nanoparticles (Figure 1). These biodegradable, biocompatible polymeric NPs have attracted significant attention as potential drug delivery systems since they can be applied in drug targeting to particular organs/tissues and as carriers of DNA in gene therapy, and are also able to deliver proteins and peptides via oral administration.

Biodegradable natural polymers include chitosan, albumin, rosin, sodium alginate and gelatin, while synthetic polymers include polylactic acid (PLA), polylactic-glycolic acid (PLGA), polycaprolactones (PCL), polycyanoacrylates and polyaminoacid conjugates)[14-17]. PLA and PLGA biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for human use.

Liposomes are spherical artificial vesicles consisting in one or more phospholipid bilayers enclosing an aqueous compartment. Liposomes can encapsulate a wide variety of lipophilic (hydrophobic) and hydrophilic drugs within their dual compartment structure. Hydrophobic drugs can be incorporated into the bilayer, while hydrophilic drugs can be contained within the inner aqueous core formed by the lipid membrane. NPs made with liposomes are the simplest form of NPs and have several advantages, such as easy preparation, good biocompatibility, reduced systemic toxicity and increased uptake[11,18]. Conventional liposomes, termed “non-stealth” liposomes, are rapidly removed from the blood circulation because of their high affinity for the RES. However, this phenomenon has been avoided by coating them with hydrophilic molecules (such as PEG derivatives) linked to the liposomal formulation by a lipid anchor. This modification significantly prolongs liposome circulation over time[19], and therefore improves pharmacological potency, reduces the dose and widens the range of indications.

In the early 1990s a new class of colloidal drug carriers, SLNs, were developed[20]. SLNs have been reported to be an alternative carrier system to emulsions, liposomes and polymeric nanoparticles. SLNs are particles measuring above the submicron range (from about 50 to 500 nm). SLNs are produced by substituting the liquid lipid (oil) with a solid lipid, i.e., the lipid is solid at both room and human body temperatures. SLN are mainly composed of physiological solid lipid dispersed in water or, if necessary, in aqueous surfactant solution. The solid lipid core may contain triglycerides, glyceride mixtures, fatty acids, steroids or waxes. SLNs offer the advantages of the traditional systems but avoid some of their major disadvantages. SLNs are relatively easy to produce without the use of organic solvents, and may be produced on a large scale at low cost[21]. They do not cause toxicity or biodegradability problems, being obtained from physiological lipids and, since the mobility of a drug in solid lipid is lower compared to that in liquid lipid, they can control drug release[22-27].

NLCs were developed at the end of the 1990s to overcome some limitations related to older generation SLNs[25,27,28]. NLCs are produced using blends of solid lipids and liquid lipids (oils), the blends being solid at room and body temperatures. Both NLCs and SLNs are made of physiological, biodegradable, and biocompatible lipids and surfactants. NLCs, similar to SLNs, are colloidal particles ranging in size from 100 to 500 nm. Compared to SLNs, NLCs possess a higher drug loading capacity, lower water content, reduced drug expulsion during storage and longer physical stability[22,23-31].

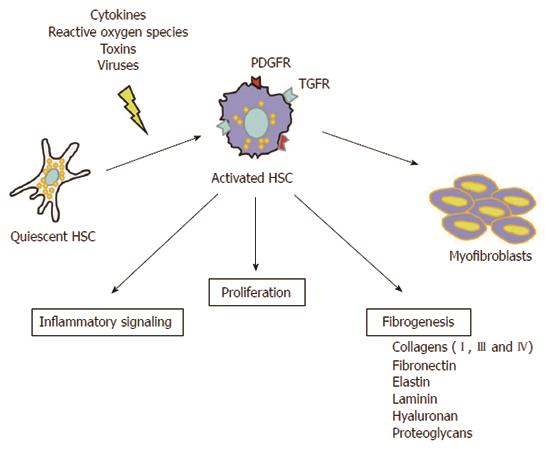

Liver fibrosis is an abnormal liver condition in which there is a scarring of the liver. It is the consequence of a chronic liver injury and a continual wound-healing process mainly triggered by hepatitis viruses (HBV and HCV) chronic infection, alcohol consumption, genetic abnormalities, steatohepatitis, autoimmune damage, etc. Key players in the fibrotic process, which takes place at the cellular and molecular levels, are the HSCs. Their activation and transformation into myofibroblasts, initiated by different types of stimuli, such as cytokines[32], reactive oxygen species[33], toxins[34] and viruses[35], determine an overproduction of extracellular matrix (mainly type I and III collagens) which greatly contributes to intrahepatic connective tissue expansion during fibrogenesis (Figure 2). Moreover, activated HSCs secrete pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory mediators which perpetuate their activated state, and due to their contractile features they also play a pivotal role in the portal hypertension setting, the major cause of clinical complications of liver cirrhosis[36,37].

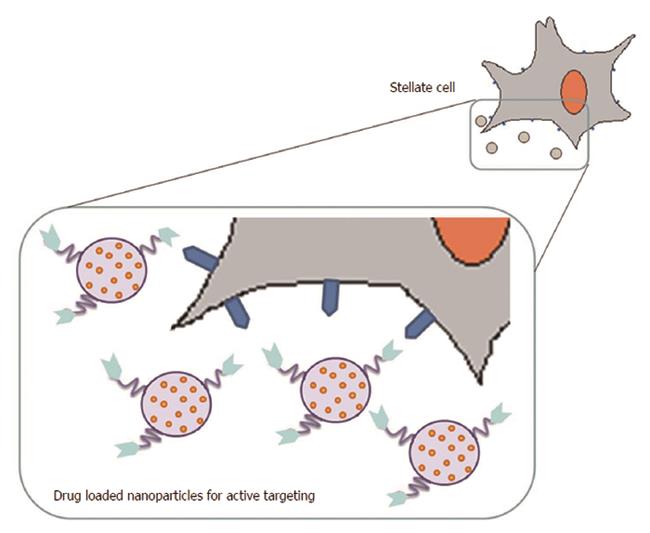

In the clinical setting, the conventional anti-fibrotic treatments are still limited, often due to non-specific drug disposition. Thus, the aim of efficient antifibrotic drug delivery using nanotechnology approaches is to achieve liver-specificity with subsequent targeting of the fibrotic region. In this context, HSCs have been the major target for delivering drugs to fibrosis using nanotechnology approaches (Figure 3).

The strongest experimental evidence on possible new approaches for the treatment of liver fibrosis derives from the use of different HSC-selective nanoparticle carriers, most of which are based on the conjugation of targeting ligands directed against receptors expressed by activated HSCs at the surface of various types of NPs. In fact, activated HSC cells express or over-express various receptors, such as mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II (M6P/IGFII) receptor, PPARs, integrins, platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs), retinol binding protein (RBP) receptor and galactosyl receptor, which could be the target of NPs.

M6P/IGFII receptor is involved in the activation of latent transforming growth factor β (L-TGFβ). M6P/IGFII receptor is highly and specifically up-regulated on activated HSC during liver fibrosis[38,39]. TGFβ is a fibrogenic cytokine with many functions, including collagen production and inhibition of its degradation[40]. TGFβ binds to the TGFβ type-II receptor on the cell surface, which then heterotetramerizes with a type-I receptor, in most cases activin-like kinase 5. Several preclinical results using different animal models of liver fibrosis suggest that selective localization of a drug to HSC can be possible by targeting the M6P/IGFII receptor. First, Beljaars et al[41] demonstrated that in rats with liver fibrosis M6P-human serum albumin (albumin chemically modified with 28 M6P groups, M6P-HSA) could be taken up and selectively accumulated in activated HSC. The binding of M6P-HSA to HSC was specific and mediated by binding to M6P/IGF-II receptor. This first evidence therefore suggested that M6P-HSA is a suitable carrier for the selective delivery of antifibrotic drugs to activated HSC. Based on these findings, Adrian et al[42,43] coupled M6P-HSA to the surface of liposomes and injected them via the penile vein in rats with liver fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation. M6P-HSA liposomes were rapidly cleared from the blood circulation in the diseased rats and mainly accumulated in the liver. These studies demonstrated that liposomes coupled with M6P-HSA are potentially effective drug carriers and therefore open up new possibilities for pharmacological interference with a disease as complex as liver fibrosis. Subsequently, to explore new potential therapeutic interventions based on a genetic approach for the treatment of liver fibrosis, inactivated hemagglutinating virus of Japan (HVJ, also known as Sendai virus) containing plasmid DNA was fused with M6P-HSA liposomes to yield HVJ liposomes that selectively target HSCs[43]. Adrian et al[44], showed that following iv injection into mice with liver fibrosis, M6P-HSA-HVJ-liposomes efficiently associated with HSC. This approach therefore offers new possibilities for treating liver fibrosis.

PPARs, which belong to the superfamily of nuclear hormone receptors with transcriptional activity controlling multiple processes, have been implicated in liver fibrogenesis[45]. To date, four isoforms of PPARs have been identified, namely PPARδ, β, γ and δ. Growing evidence shows that activated HSCs express PPARδ and its expression exerts important effects on fibrogenesis in animal models[46], and that treatment with PPARδ ligands, Wy-14643 (WY) or fenofibrate, dramatically reduces hepatic fibrosis[47]. PPARβ and PPARδ are also highly expressed in HSCs, and their activation increases hepatic fibrosis[48]. There is clear evidence that activation of HSCs and their transdifferentiation into myofibroblasts is accompanied by significantly decreased PPARγ expression, and that treatment with PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone inhibits HSC activation[49]. Therefore, PPARs are considered a promising drug target for antifibrotic therapy[50-52]. M6P-HSA-conjugated liposomes have also been used to deliver ligands for PPAR to activated HSCs. Recently, Patel et al[53] reported a significant enhancement of liver uptake, improvement in histopathological morphology and decreased fibrosis grade when the PPARγ ligand rosiglitazone was loaded in M6P-HSA-conjugated liposomes and administrated intravenously in rats with liver fibrosis.

Activated HSCs express increasing amounts of integrins. Integrins are a large family of heterodimeric cell surface receptors which mediate the interaction between cells and extracellular matrix molecules (such as collagens and fibronectin) and recognize a common motif in their ligands, among which the best studied is the RGD sequence (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid)[54-56]. Collagen VI, abnormally produced in the liver by activated HSCs and deposited during fibrogenesis, is recognized by cell-surface integrins, mainly integrin δ1β1, through the specific interaction of the receptor with the RGD sequence present in the matrix molecule. Therefore, the RGD sequence has been used as a homing device to target integrins and hence HSCs in fibrotic liver. In 2000 a carrier which showed binding and internalization to HSC was successfully used for the first time[57], suggesting the possibility to deliver anti-fibrotic agents directly to HSC. Subsequently, Du et al[58] developed cyclic RGD-labeled sterically-stabilized liposomes (SSLs) to deliver IFNδ-1b to HSC. They demonstrated that cyclic RGD peptide-labeled liposomes were selectively taken up by activated HSCs in a liver fibrosis rat model, and that liposome encapsulated IFNδ-1b displayed an improved efficiency in blocking fibrogenesis. In another study, Li et al[59] also used SSLs labeled with cyclic RGD peptide to encapsulate hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), in order to prevent its degradation and therefore to reverse fibrogenesis processes[60]. When HGF was encapsulated in SSL labeled with cyclic RGD peptide (RGD-SSL-HGF) it was more effective than SSL-HGF in promoting liver fibrosis regression in cirrhotic rats, indicating that HGF loaded in RGD-SSL enhanced its effect on activated HSCs[60].

PDGF is the most potent proliferative factor in liver fibrosis. Its receptor (PDGFR) has two forms, PDGFRδ and PDGFRβ. PGFRs are cell surface tyrosine kinase receptors for members of the PDGF family. In particular, PDGF-β receptor is highly upregulated on activated HSCs[61]. Recent studies in rats with hepatic fibrosis showed that pPB-SSL-IFN-γ, a targeted SSL modified by a cyclic peptide (pPB) with affinity for the PDGF-β receptor to deliver IFN-γ (pPB-SSL-IFN-γ) to HSCs, improves the anti-fibrotic effects of IFN-γ and reduces its side effects to some extent[62,63].

RBP receptor expressed by HSCs, is involved in the uptake and storage of vitamin A. Sato et al[64] assessed the anti-fibrotic properties of vitamin A-coupled liposomes containing small interfering RNA (siRNA) against gp46, the rat homolog of human heat shock protein 47 and involved in the inhibition of collagen secretion, in three experimental models of liver fibrosis induced by dimethylnitrosamine, carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), and bile duct ligation. They showed that the treatment decreased collagen deposition, induced apoptosis of HSCs, improved liver function tests and prolonged survival in the treated rats.

Hepatic fibrosis is also the result of oxidative damage to the liver due to exposure to environmental metalloid toxicants. Therefore, a promising strategy has been developed to deliver antioxidants to damaged liver by nanocarriers. The galactosyl receptor expressed on the hepatocytes mediates the internalization of molecular asialoglycoproteins and small particles. With this in mind, liposomes decorated with p-aminophenyl δ-D-galactopyranoside, which binds to galactosyl receptor, have been used as carriers for targeted iv delivery of the antioxidant flavonoid quercetin (QC) in animals with liver fibrosis[65,66]. It has been shown that the administration of QC loaded in galactosylated liposomes in rats results in the maximum prevention of arsenic deposition (a contaminant responsible for oxidative damage present in drinking water, particularly in developing countries such as India and Bangladesh) and protects the liver from sodium arsenite (NaAsO2)-induced collagen deposition and fibrosis initiation. However, whereas free QC does not protects rats from oxidative damage, galoctosylated liposomes QC might be therapeutically useful to prevent NaAsO2-induced acute liver toxicity.

Oxymatrine (OM) is an alkaloid extracted from the medicinal plant Sophora alopecuroides L. which, among its multiple pharmacological functions, can induce apoptotic cell death in different cell types[67,68] and exerts antiviral effects, inhibiting HBV and HCV replication[69,70]. In addition, OM has also been demonstrated to have anti-fibrotic effects, being effective in reducing collagen production and deposition in CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in rats[71]. Based on these findings, Chai et al[72] used OM-RGD liposomes in both in vitro and in vivo experiments and demonstrated that delivery of OM to HSCs with this formulation attenuates hepatic fibrosis by inhibiting viability and inducing HSC apoptosis, thus highlighting its possible application in the treatment of hepatic fibrosis. The influence of OM on the fibrotic process has also been evaluated in a bile duct ligation rat model of liver fibrosis using self-assembled polymeric vesicles based on biodegradable poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(e-caprolactone) (PEG-b-PCL), referred to as polymersomes (PM), and modified with RGD peptide to obtain RGD-PM-OM[73]. Yang et al[73], demonstrated that intravenous injection of RGD-PM-OM and PM-OM formulations showed significant benefits in ameliorating the degree of liver injury and fibrosis as shown by lower levels of fibrosis markers in the serum compared to free OM. This novel approach therefore appears to be more effective than conventional treatment with OM.

Curcumin or diferuloylmethane, a yellow polyphenol extracted from the rhizome of turmeric Curcuma longa, has been extensively studied for its therapeutic effects in a variety of disorders because of its antineoplastic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects[74-76]. Several studies have shown its potential anti-fibrotic activity[77-84] but the compound has poor aqueous solubility, which results in low bioavailability and low concentrations at the target site[85,86]. Consequently, nanotechnology approaches have been developed to deliver curcumin to targets. For example Bisht et al[87] developed a polymeric nanoparticle formulation of curcumin (NanoCurcTM). Nanocurcumin was synthesized utilizing the micellar aggregates of cross-linked and random copolymers of N-isopropylacrylamide, with N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone and poly(ethylene glycol) monoacrylate (PEG-A). Nanocurcumin showed to be readily dispersed in aqueous media with a comparable in vitro therapeutic efficacy to free curcumin against a panel of human cancer cell lines[87]. The same authors subsequently performed in vivo studies using NanoCurc™ to treat animals with hepatic injury and fibrosis induced by CCl4 administration[88]. Results following intraperitoneal injection of NanoCurcTM were extremely promising, as NanoCurcTM enhanced the bioavailability of intrahepatic curcumin concentrations compared to control void NPs, attenuated hepatocellular injury and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibited CCl4-induced liver injury, prevented hepatic fibrosis and induced HSC apoptosis. The exact mechanism by which curcumin induces a protective hepatocellular environment is not clear. Curcumin might work through multiple mechanisms. As reported by Bisht et al[88] NanoCurcTM accumulates in hepatocytes and in the non-parenchymal cell compartment, which contains pro-fibrotic stellate cells and myofibroblasts. Authors have demonstrated that NanoCurcTM inhibits pro-fibrogenic transcripts associated with activated myofibroblasts and directly induces HSC apoptosis. However, another possibility is that NanoCurcTM might also affect hepatic progenitor cells or bile duct cells and thus ameliorate the effects of CCl4-induced liver injury by influencing these cells.

The extremely wide diffusion of CLD worldwide and the relatively ineffective therapeutic options especially for advanced liver fibrosis demand new drugs or new drug delivery strategies to cure liver fibrosis. Therapies based on nanotechnologies have emerged as an innovative and promising alternative to conventional therapies. The number of NPs used in biomedical research and drug delivery is rapidly increasing. Several reports in the literature, most of all in animal models, have shown that different HSC-selective NP carriers, based on the conjugation of targeting ligands directed against several receptors expressed by activated HSCs at the surface, can reduce liver fibrosis. These data, if confirmed in humans, could open up a new era in the treatment of liver fibrosis. In the next few years the clinical validation of CLD therapies based on nanotechnologies will hopefully be demonstrated.

However, much more needs to be done, particularly because the use of nanoparticles also creates unique environmental and societal challenges[89]. Toxicity associated with nanomaterials should be considered before NPs are widely utilized as drug delivery systems, especially for inorganic nanoparticles[90,91]. In this respect, the risk associated with organic NPs seems to be less problematic because this type of nanoparticles are very often typically either made from, or covered with natural or highly biocompatible polymers (such as PEG)[92].

Finally, it is necessary to develop a regulatory framework based on objective scientific research which will ensure that human exposure to unwanted engineered nanomaterials in the environment will be limited to safe levels. However, the therapeutic use of nanomaterials in medicine requires a different framework in which the therapeutic benefits will be balanced against the potentially harmful risks.

P- Reviewers: Han T, Ji G, Ramani K, Tsuchiya A S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Rockey DC. Current and future anti-fibrotic therapies for chronic liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2008;12:939-962, xi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Long-circulating and target-specific nanoparticles: theory to practice. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:283-318. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Demoy M, Gibaud S, Andreux JP, Weingarten C, Gouritin B, Couvreur P. Splenic trapping of nanoparticles: complementary approaches for in situ studies. Pharm Res. 1997;14:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li SD, Huang L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:496-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1112] [Cited by in RCA: 1130] [Article Influence: 66.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Owens DE, Peppas NA. Opsonization, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of polymeric nanoparticles. Int J Pharm. 2006;307:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2537] [Cited by in RCA: 2461] [Article Influence: 123.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jokerst JV, Lobovkina T, Zare RN, Gambhir SS. Nanoparticle PEGylation for imaging and therapy. Nanomedicine (Lond). 2011;6:715-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1748] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 104.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Nanomedicine: current status and future prospects. FASEB J. 2005;19:311-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1369] [Cited by in RCA: 1107] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sandhiya S, Dkhar SA, Surendiran A. Emerging trends of nanomedicine--an overview. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2009;23:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Teli MK, Mutalik S, Rajanikant GK. Nanotechnology and nanomedicine: going small means aiming big. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:1882-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sekhon BS, Kamboj SR. Inorganic nanomedicine--part 2. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:612-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heneweer C, Gendy SE, Peñate-Medina O. Liposomes and inorganic nanoparticles for drug delivery and cancer imaging. Ther Deliv. 2012;3:645-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chithrani DB. Nanoparticles for improved therapeutics and imaging in cancer therapy. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2010;4:171-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Das A, Mukherjee P, Singla SK, Guturu P, Frost MC, Mukhopadhyay D, Shah VH, Patra CR. Fabrication and characterization of an inorganic gold and silica nanoparticle mediated drug delivery system for nitric oxide. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:305102. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lebre F, Bento D, Jesus S, Borges O. Chitosan-based nanoparticles as a hepatitis B antigen delivery system. Methods Enzymol. 2012;509:127-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Kamaly N, Xiao Z, Valencia PM, Radovic-Moreno AF, Farokhzad OC. Targeted polymeric therapeutic nanoparticles: design, development and clinical translation. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2971-3010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1402] [Cited by in RCA: 1194] [Article Influence: 91.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Elsabahy M, Wooley KL. Design of polymeric nanoparticles for biomedical delivery applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2545-2561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1402] [Cited by in RCA: 1185] [Article Influence: 91.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Craparo EF, Teresi G, Licciardi M, Bondí ML, Cavallaro G. Novel composed galactosylated nanodevices containing a ribavirin prodrug as hepatic cell-targeted carriers for HCV treatment. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2013;9:1107-1122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dreaden EC, Austin LA, Mackey MA, El-Sayed MA. Size matters: gold nanoparticles in targeted cancer drug delivery. Ther Deliv. 2012;3:457-478. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Immordino ML, Dosio F, Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int J Nanomedicine. 2006;1:297-315. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Müller RH, Mäder K, Gohla S. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) for controlled drug delivery - a review of the state of the art. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2000;50:161-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2418] [Cited by in RCA: 2208] [Article Influence: 88.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bondì ML, Fontana G, Carlisi B, Giammona G. Preparation and characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles containing cloricromene. Drug Deliv. 2003;10:245-250. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wissing SA, Kayser O, Müller RH. Solid lipid nanoparticles for parenteral drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1257-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 988] [Cited by in RCA: 873] [Article Influence: 41.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Puri A, Loomis K, Smith B, Lee JH, Yavlovich A, Heldman E, Blumenthal R. Lipid-based nanoparticles as pharmaceutical drug carriers: from concepts to clinic. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26:523-580. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Pardeike J, Hommoss A, Müller RH. Lipid nanoparticles (SLN, NLC) in cosmetic and pharmaceutical dermal products. Int J Pharm. 2009;366:170-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 900] [Cited by in RCA: 823] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pardeshi C, Rajput P, Belgamwar V, Tekade A, Patil G, Chaudhary K, Sonje A. Solid lipid based nanocarriers: an overview. Acta Pharm. 2012;62:433-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA. Nanostructured lipid matrices for improved microencapsulation of drugs. Int J Pharm. 2002;242:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 751] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bondì ML, Azzolina A, Craparo EF, Capuano G, Lampiasi N, Giammona G, Cervello M. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) containing nimesulide: preparation, characterization and in cytotoxicity studies. Curr Nanosc. 2009;5:39-44. |

| 28. | Müller RH, Radtke M, Wissing SA. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic and dermatological preparations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54 Suppl 1:S131-S155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1387] [Cited by in RCA: 1274] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Müller RH, Petersen RD, Hommoss A, Pardeike J. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in cosmetic dermal products. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:522-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 434] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bondì ML, Craparo EF, Giammona G, Cervello M, Azzolina A, Diana P, Martorana A, Cirrincione G. Nanostructured lipid carriers-containing anticancer compounds: preparation, characterization, and cytotoxicity studies. Drug Deliv. 2007;14:61-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bondi ML, Azzolina A, Craparo EF, Lampiasi N, Capuano G, Giammona G, Cervello M. Novel cationic solid-lipid nanoparticles as non-viral vectors for gene delivery. J Drug Target. 2007;15:295-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Li JT, Liao ZX, Ping J, Xu D, Wang H. Molecular mechanism of hepatic stellate cell activation and antifibrotic therapeutic strategies. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:419-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | He Q, Zhang J, Chen F, Guo L, Zhu Z, Shi J. An anti-ROS/hepatic fibrosis drug delivery system based on salvianolic acid B loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7785-7796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Siegmund SV, Dooley S, Brenner DA. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Dig Dis. 2005;23:264-274. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Zan Y, Zhang Y, Tien P. Hepatitis B virus e antigen induces activation of rat hepatic stellate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:391-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1096] [Cited by in RCA: 1374] [Article Influence: 98.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | de Bleser PJ, Jannes P, van Buul-Offers SC, Hoogerbrugge CM, van Schravendijk CF, Niki T, Rogiers V, van den Brande JL, Wisse E, Geerts A. Insulinlike growth factor-II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor is expressed on CCl4-exposed rat fat-storing cells and facilitates activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta in cocultures with sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology. 1995;21:1429-1437. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Greupink R, Bakker HI, van Goor H, de Borst MH, Beljaars L, Poelstra K. Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-Like growth factor-II receptors may represent a target for the selective delivery of mycophenolic acid to fibrogenic cells. Pharm Res. 2006;23:1827-1834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hayashi H, Sakai T. Biological Significance of Local TGF-β Activation in Liver Diseases. Front Physiol. 2012;3:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Beljaars L, Molema G, Weert B, Bonnema H, Olinga P, Groothuis GM, Meijer DK, Poelstra K. Albumin modified with mannose 6-phosphate: A potential carrier for selective delivery of antifibrotic drugs to rat and human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 1999;29:1486-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Adrian JE, Poelstra K, Scherphof GL, Molema G, Meijer DK, Reker-Smit C, Morselt HW, Kamps JA. Interaction of targeted liposomes with primary cultured hepatic stellate cells: Involvement of multiple receptor systems. J Hepatol. 2006;44:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Adrian JE, Kamps JA, Scherphof GL, Meijer DK, van Loenen-Weemaes AM, Reker-Smit C, Terpstra P, Poelstra K. A novel lipid-based drug carrier targeted to the non-parenchymal cells, including hepatic stellate cells, in the fibrotic livers of bile duct ligated rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1430-1439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Adrian JE, Kamps JA, Poelstra K, Scherphof GL, Meijer DK, Kaneda Y. Delivery of viral vectors to hepatic stellate cells in fibrotic livers using HVJ envelopes fused with targeted liposomes. J Drug Target. 2007;15:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zardi EM, Navarini L, Sambataro G, Piccinni P, Sambataro FM, Spina C, Dobrina A. Hepatic PPARs: their role in liver physiology, fibrosis and treatment. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:3370-3396. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Rodríguez-Vilarrupla A, Laviña B, García-Calderó H, Russo L, Rosado E, Roglans N, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC. PPARα activation improves endothelial dysfunction and reduces fibrosis and portal pressure in cirrhotic rats. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1033-1039. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Toyama T, Nakamura H, Harano Y, Yamauchi N, Morita A, Kirishima T, Minami M, Itoh Y, Okanoue T. PPARalpha ligands activate antioxidant enzymes and suppress hepatic fibrosis in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:697-704. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Kostadinova R, Montagner A, Gouranton E, Fleury S, Guillou H, Dombrowicz D, Desreumaux P, Wahli W. GW501516-activated PPARβ/δ promotes liver fibrosis via p38-JNK MAPK-induced hepatic stellate cell proliferation. Cell Biosci. 2012;2:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Chen H, He YW, Liu WQ, Zhang JH. Rosiglitazone prevents murine hepatic fibrosis induced by Schistosoma japonicum. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2905-2911. [PubMed] |

| 50. | Zhang F, Kong D, Lu Y, Zheng S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ as a therapeutic target for hepatic fibrosis: from bench to bedside. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:259-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Rodríguez-Vilarrupla A, Laviña B, García-Calderó H, Russo L, Rosado E, Roglans N, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC. PPARα activation improves endothelial dysfunction and reduces fibrosis and portal pressure in cirrhotic rats. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1033-1039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Zhang F, Lu Y, Zheng S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ cross-regulation of signaling events implicated in liver fibrogenesis. Cell Signal. 2012;24:596-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Patel G, Kher G, Misra A. Preparation and evaluation of hepatic stellate cell selective, surface conjugated, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligand loaded liposomes. J Drug Target. 2012;20:155-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Patsenker E, Stickel F. Role of integrins in fibrosing liver diseases. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G425-G434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Levine D, Rockey DC, Milner TA, Breuss JM, Fallon JT, Schnapp LM. Expression of the integrin alpha8beta1 during pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1927-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Zhou X, Murphy FR, Gehdu N, Zhang J, Iredale JP, Benyon RC. Engagement of alphavbeta3 integrin regulates proliferation and apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23996-24006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Beljaars L, Molema G, Schuppan D, Geerts A, De Bleser PJ, Weert B, Meijer DK, Poelstra K. Successful targeting to rat hepatic stellate cells using albumin modified with cyclic peptides that recognize the collagen type VI receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12743-12751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Du SL, Pan H, Lu WY, Wang J, Wu J, Wang JY. Cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp peptide-labeled liposomes for targeting drug therapy of hepatic fibrosis in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:560-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Li F, Sun JY, Wang JY, Du SL, Lu WY, Liu M, Xie C, Shi JY. Effect of hepatocyte growth factor encapsulated in targeted liposomes on liver cirrhosis. J Control Release. 2008;131:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kim WH, Matsumoto K, Bessho K, Nakamura T. Growth inhibition and apoptosis in liver myofibroblasts promoted by hepatocyte growth factor leads to resolution from liver cirrhosis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1017-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Bonner JC. Regulation of PDGF and its receptors in fibrotic diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:255-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Li Q, Yan Z, Li F, Lu W, Wang J, Guo C. The improving effects on hepatic fibrosis of interferon-γ liposomes targeted to hepatic stellate cells. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:265101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Li F, Li QH, Wang JY, Zhan CY, Xie C, Lu WY. Effects of interferon-gamma liposomes targeted to platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta on hepatic fibrosis in rats. J Control Release. 2012;159:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Sato Y, Murase K, Kato J, Kobune M, Sato T, Kawano Y, Takimoto R, Takada K, Miyanishi K, Matsunaga T. Resolution of liver cirrhosis using vitamin A-coupled liposomes to deliver siRNA against a collagen-specific chaperone. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:431-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Mandal AK, Das S, Basu MK, Chakrabarti RN, Das N. Hepatoprotective activity of liposomal flavonoid against arsenite-induced liver fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:994-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Ghosh D, Ghosh S, Sarkar S, Ghosh A, Das N, Das Saha K, Mandal AK. Quercetin in vesicular delivery systems: evaluation in combating arsenic-induced acute liver toxicity associated gene expression in rat model. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;186:61-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ling Q, Xu X, Wei X, Wang W, Zhou B, Wang B, Zheng S. Oxymatrine induces human pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells apoptosis via regulating expression of Bcl-2 and IAP families, and releasing of cytochrome c. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Dong XQ, Yu WH, Hu YY, Zhang ZY, Huang M. Oxymatrine reduces neuronal cell apoptosis by inhibiting Toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor kappa-B-dependent inflammatory responses in traumatic rat brain injury. Inflamm Res. 2011;60:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Chen XS, Wang GJ, Cai X, Yu HY, Hu YP. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus by oxymatrine in vivo. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:49-52. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Ding CB, Zhang JP, Zhao Y, Peng ZG, Song DQ, Jiang JD. Zebrafish as a potential model organism for drug test against hepatitis C virus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Wu XL, Zeng WZ, Jiang MD, Qin JP, Xu H. Effect of Oxymatrine on the TGFbeta-Smad signaling pathway in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2100-2105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Chai NL, Fu Q, Shi H, Cai CH, Wan J, Xu SP, Wu BY. Oxymatrine liposome attenuates hepatic fibrosis via targeting hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4199-4206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Yang J, Hou Y, Ji G, Song Z, Liu Y, Dai G, Zhang Y, Chen J. Targeted delivery of the RGD-labeled biodegradable polymersomes loaded with the hydrophilic drug oxymatrine on cultured hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis in rats. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2014;52:180-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Gupta SC, Patchva S, Aggarwal BB. Therapeutic roles of curcumin: lessons learned from clinical trials. AAPS J. 2013;15:195-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1048] [Cited by in RCA: 1227] [Article Influence: 94.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 75. | Notarbartolo M, Poma P, Perri D, Dusonchet L, Cervello M, D’Alessandro N. Antitumor effects of curcumin, alone or in combination with cisplatin or doxorubicin, on human hepatic cancer cells. Analysis of their possible relationship to changes in NF-kB activation levels and in IAP gene expression. Cancer Lett. 2005;224:53-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Labbozzetta M, Notarbartolo M, Poma P, Giannitrapani L, Cervello M, Montalto G, D’Alessandro N. Significance of autologous interleukin-6 production in the HA22T/VGH cell model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:268-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Yao QY, Xu BL, Wang JY, Liu HC, Zhang SC, Tu CT. Inhibition by curcumin of multiple sites of the transforming growth factor-beta1 signalling pathway ameliorates the progression of liver fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Tu CT, Yao QY, Xu BL, Wang JY, Zhou CH, Zhang SC. Protective effects of curcumin against hepatic fibrosis induced by carbon tetrachloride: modulation of high-mobility group box 1, Toll-like receptor 4 and 2 expression. Food Chem Toxicol. 2012;50:3343-3351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Wang ME, Chen YC, Chen IS, Hsieh SC, Chen SS, Chiu CH. Curcumin protects against thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis by attenuating the inflammatory response and inducing apoptosis of damaged hepatocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 2012;23:1352-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Wu SJ, Tam KW, Tsai YH, Chang CC, Chao JC. Curcumin and saikosaponin a inhibit chemical-induced liver inflammation and fibrosis in rats. Am J Chin Med. 2010;38:99-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Vizzutti F, Provenzano A, Galastri S, Milani S, Delogu W, Novo E, Caligiuri A, Zamara E, Arena U, Laffi G. Curcumin limits the fibrogenic evolution of experimental steatohepatitis. Lab Invest. 2010;90:104-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Shu JC, He YJ, Lv X, Ye GR, Wang LX. Curcumin prevents liver fibrosis by inducing apoptosis and suppressing activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Nat Med. 2009;63:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Fu Y, Zheng S, Lin J, Ryerse J, Chen A. Curcumin protects the rat liver from CCl4-caused injury and fibrogenesis by attenuating oxidative stress and suppressing inflammation. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:399-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Bruck R, Ashkenazi M, Weiss S, Goldiner I, Shapiro H, Aeed H, Genina O, Helpern Z, Pines M. Prevention of liver cirrhosis in rats by curcumin. Liver Int. 2007;27:373-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Anand P, Kunnumakkara AB, Newman RA, Aggarwal BB. Bioavailability of curcumin: problems and promises. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:807-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3258] [Cited by in RCA: 3624] [Article Influence: 201.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Sharma RA, Steward WP, Gescher AJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of curcumin. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;595:453-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Bisht S, Feldmann G, Soni S, Ravi R, Karikar C, Maitra A, Maitra A. Polymeric nanoparticle-encapsulated curcumin (“nanocurcumin”): a novel strategy for human cancer therapy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2007;5:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 690] [Cited by in RCA: 705] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 88. | Bisht S, Khan MA, Bekhit M, Bai H, Cornish T, Mizuma M, Rudek MA, Zhao M, Maitra A, Ray B. A polymeric nanoparticle formulation of curcumin (NanoCurc™) ameliorates CCl4-induced hepatic injury and fibrosis through reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and stellate cell activation. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1383-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Elsaesser A, Howard CV. Toxicology of nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:129-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Soenen SJ, Rivera-Gil P, Montenegro JM, Parak WJ, De Smedt S, Braeckmans K. Cellular toxicity of inorganic nanoparticles: Common aspects and guidelines for improved nanotoxicity evaluation. Nano Today. 2011;6:446-465. |

| 91. | Soenen SJ, Manshian B, Montenegro JM, Amin F, Meermann B, Thiron T, Cornelissen M, Vanhaecke F, Doak S, Parak WJ. Cytotoxic effects of gold nanoparticles: a multiparametric study. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5767-5783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | McClements DJ. Edible lipid nanoparticles: digestion, absorption, and potential toxicity. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:409-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |