Published online Jun 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6981

Revised: February 19, 2014

Accepted: March 19, 2014

Published online: June 14, 2014

Processing time: 219 Days and 18.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate the necessity and correctness of acid suppression pre- and post-gastrectomy among gastric carcinoma (GC) patients.

METHODS: From June 2011 to April 2013, 99 patients who were diagnosed with GC or adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction (type II or III) and needed surgical management were enrolled. They all underwent gastrectomy by the same operators [35 undergoing total gastrectomy (TG) plus Roux-en-Y reconstruction, 34 distal gastrectomy (DG) plus Billroth I reconstruction, and 30 proximal gastrectomy (PG) plus gastroesophagostomy]. We collected and analyzed their gastrointestinal juice and tissues from the pre-operational day to the 5th day post-operation, and 6 mo post-surgery. Gastric pH was detected with a precise acidity meter. Gastric juice contents including potassium, sodium and bicarbonate ions, urea nitrogen, direct and indirect bilirubin, and bile acid were detected using Automatic Biochemical Analyzer. Data regarding tumor size, histological type, tumor penetration and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage were obtained from the pathological records. Reflux symptoms pre- and 6 mo post-gastrectomy were evaluated by reflux disease questionnaire (RDQ) and gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire (GERD-Q). SPSS 16.0 was applied to analyze the data.

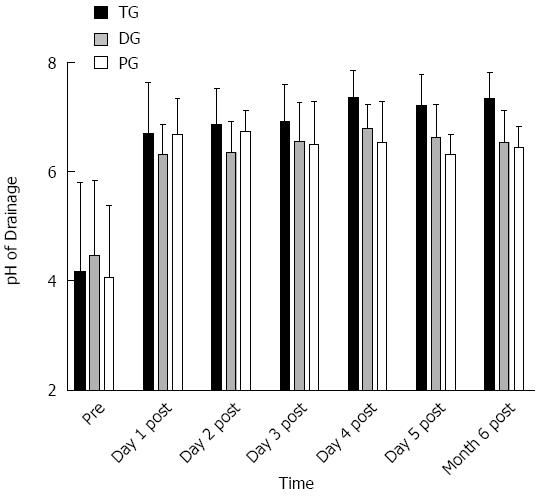

RESULTS: Before surgery, gastric pH was higher than the threshold of hypoacidity (4.25 ± 1.45 vs 3.5, P = 0.000), and significantly affected by age, tumor size and differentiation grade, and potassium and bicarbonate ions; advanced malignancies were accompanied with higher pH compared with early ones (4.49 ± 1.31 vs 3.66 ± 1.61, P = 0.008). After operation, gastric pH in all groups was of weak-acidity and significantly higher than that pre-gastrectomy; on days 3-5, comparisons of gastric pH were similar between the 3 groups. Six months later, gastric pH was comparable to that on days 3-5; older patients were accompanied with higher total bilirubin level, indicating more serious reflux (r = 0.238, P = 0.018); the TG and PG groups had higher RDQ (TG vs DG: 15.80 ± 5.06 vs 12.26 ± 2.14, P = 0.000; PG vs DG: 15.37 ± 3.49 vs 12.26 ± 2.14, P = 0.000) and GERD-Q scores (TG vs DG: 10.54 ± 3.16 vs 9.15 ± 2.27, P = 0.039; PG vs DG: 11.00 ± 2.07 vs 9.15 ± 2.27, P = 0.001) compared with the DG group; all gastric juice contents except potassium ion significantly rose; reflux symptom was significantly associated with patient’s body mass index, direct and indirect bilirubin, and total bile acid, while pH played no role.

CONCLUSION: Acidity is not an important factor causing unfitness among GC patients. There is no need to further alkalify gastrointestinal juice both pre- and post-gastrectomy.

Core tip: Necessity of peri-gastrectomy acid suppression for gastric cancer patients remains controversial. This innovative prospective study showed: before surgery, gastric pH was higher than the threshold of hypoacidity, and affected by age, tumor size and differentiation grade, and potassium and bicarbonate ions; advanced malignancies were accompanied with higher pH; after operation, gastric pH in all groups was of weak-acidity and higher than that pre-gastrectomy; six months later, gastric pH was comparable to that on days 3-5; reflux symptom was significantly associated with patient’s body mass index, direct and indirect bilirubin, and total bile acid, while pH played no role.

- Citation: Huang L, Xu AM, Li TJ, Han WX, Xu J. Should peri-gastrectomy gastric acidity be our focus among gastric cancer patients? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(22): 6981-6988

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i22/6981.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6981

Although the incidence and cancer-related mortality have been decreasing steadily during the past century, gastric carcinoma (GC) remains one of the most common malignancies and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide[1]. Approximately 2/3 of GC patients are at advanced stages when initially diagnosed, with a 5-year survival rate of about 25%[2,3]. Surgery is the major treatment, which includes total gastrectomy (TG), distal gastrectomy (DG) and proximal gastrectomy (PG). D2 lymphonectomy is strongly recommended for its assurance of relatively high survival and low recurrence rates[4]. With the advancement in gastrointestinal operation and the improvement of the comprehensive methods to treat cancer, patients undergoing gastrectomy can enjoy a longer life, leading to their growing focus on the post-surgical quality of life (QOL). Nowadays gastroenterologists are trying harder to reduce complications and improve QOL after patients’ stomach is removed.

Reflux is common among patients after stomach resection, affecting their QOL greatly[4,5]. Studies on the correlation between gastric juice contents and stomach diseases have been widely conducted, and studies of reflux are mainly concentrated on patients with intact stomach[4-7]. However, the comparison between pre- and post-surgery has been rarely observed. We used to suppress acid hoping to release reflux symptoms[5-7], while the essentiality and rationality are debatable. In this study, we detected the acidity and contents of gastrointestinal juice, and assessed reflux among GC patients pre- and post-TG, DG and PG, aiming at clarifying whether patients benefit from acid suppression.

All patients enrolled in our study were diagnosed with GC or adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction (type II or III)[8] without metastasis by pathology and imaging, and needed surgical management. They were in relatively fine overall conditions (hemoglobin > 90 g/L, and serum albumin > 30 g/L) without any disease that could cause a significant difference of pressure between thoracic and abdominal cavities, severe dysfunction of important organs or systematic unfitness like refractory ascites or dyscrasia. Before operation, they were certified to be free from successive diseases associated with reflux including esophagitis by endoscopy, and all got Reflux Disease Questionnaire (RDQ)[9] scores less than 12, and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Questionnaire (GERD-Q)[10] scores less than 8, indicating no reflux. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient, and the study was permitted by Ethics Committee of Anhui Medical University and carried out according to Declaration of Helsinki[11].

Patients undergoing multivisceral resection or having other gastroenterological diseases, including hiatus hernia indicated by X-ray and gastroscopy, were excluded from our study. The selected patients did not have a history of gastrectomy and were not dependent on any kind of drug affecting the secretion of gastrointestinal fluid. They had not received any chemotherapy or radiotherapy before. Drainage samples collected were not polluted by blood or remnant food, and we had complete data of each of them.

A total of 118 patients treated in the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University from June 11th, 2011 to April 23rd, 2013 were chosen according to the criteria above. Finally we got 99 patients’ drainage samples, with 35 undergoing TG plus Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TG group), 34 DG plus Billroth I reconstruction (DG group), and 30 PG plus gastroesophagostomy (PG group), apart from 19 individuals (5 in TG group, 8 DG and 6 PG) who quit the study half-way or were affected greatly by irrelevant factors or whose samples or data went against our standards (Table 1).

| Total gastrectomy | Distal gastrectomy | Proximal gastrectomy | |

| Number of patients | 35 | 34 | 30 |

| Gender (male/female) | 20/15 | 19/15 | 19/11 |

| Smoking (yes/no) | 19/16 | 18/16 | 18/12 |

| Drinking (yes/no) | 17/18 | 18/16 | 17/13 |

| Age (yr) | 62.49 ± 9.69 | 63.68 ± 9.48 | 59.40 ± 10.61 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 20.55 ± 4.02 | 20.92 ± 2.57 | 19.70 ± 2.43 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 114.83 ± 26.00 | 125.59 ± 24.99 | 122.23 ± 21.46 |

| Lymphocyte count (109/L) | 1.61 ± 0.50 | 1.34 ± 0.47 | 1.65 ± 0.51 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 38.43 ± 4.92 | 41.58 ± 3.50 | 40.99 ± 1.85 |

| Pre-albumin (mg/L) | 252.20 ± 60.65 | 282.71 ± 70.35 | 262.23 ± 45.65 |

| RDQ score pre-operation | 3.77 ± 2.58 | 3.35 ± 2.36 | 3.50 ± 2.36 |

| GERD-Q score pre-operation | 1.49 ± 1.15 | 1.47 ± 1.05 | 1.63 ± 1.40 |

| Days in hospital pre-operation | 3.09 ± 0.92 | 3.06 ± 0.92 | 3.00 ± 0.87 |

| Days to peri-bed activities post-operation | 1.14 ± 0.36 | 1.12 ± 0.33 | 1.13 ± 0.35 |

| Days to borborygmus recovery post-operation | 1.51 ± 0.51 | 1.56 ± 0.50 | 1.57 ± 0.50 |

| Flatus duration post-operation (d) | 3.11 ± 0.63 | 3.29 ± 0.80 | 3.47 ± 0.68 |

| Transverse diameter of tumor (cm) | 4.71 ± 1.87 | 4.90 ± 1.46 | 4.78 ± 2.04 |

| Longitudinal diameter of tumor (cm) | 4.06 ± 1.86 | 4.20 ± 1.15 | 4.40 ± 1.54 |

| Depth of tumor (cm) | 1.41 ± 0.64 | 1.66 ± 0.47 | 1.16 ± 0.66 |

| Tumor stage (early/advanced) | 4/31 | 5/29 | 3/27 |

| Tumor differentiation (well/moderately/poorly) | 6/15/14 | 7/12/15 | 4/13/13 |

| Tumor TNM classification (I/II/III)1 | 4/5/26 | 7/6/21 | 3/8/19 |

| Postoperative NRS score | 3.34 ± 0.97 | 3.32 ± 0.98 | 3.30 ± 1.02 |

Before surgery, the selected patients were forbidden from food, drink, cigarette and alcohol for more than 12 h, and drugs affecting the acidity of gastrointestinal juice like proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs), anticholinergic agents, and cortical hormones for more than 1 d, and had only some liquid food the night before. If the tumor caused obvious obstruction, the patients were required to have easily digestible food 2 d before. At 7:00 on the morning of the operation day, we required the patient to lie on his/her left side in a quiet circumstance, put the gastric tube into his/her digestive tract until the end reached the mucoid pool[12], aspirated about 10 mL fluid with a syringe, and wrote down the depth the tube had been pushed in. We fixed the tube to the same depth as that pre-operation after surgery, and all kinds of drugs affecting the secretion of gastrointestinal fluid were abandoned. Patients all received parenteral nutrition, and we changed the suction disc at 7:00 pm, and collected about 10 mL fluid again from inside the disc at 7:00 am the next day, from the 1st to the 5th days post-operation. Gastrointestinal juice (10 mL) was collected again via gastroscopy 6 mo post-gastrectomy. No acid-suppressing drugs were applied during this postsurgical period.

We labeled all samples and detected their pH with a precise acidity meter (precision: 0.01) right after we got them. Gastric juice contents including potassium, sodium and bicarbonate ions, urea nitrogen, direct and indirect bilirubin and total bile acid were detected using Automatic Biochemical Analyzer provided by Roche, Germany (type: Modular DPP). The rest samples were preserved in a refrigerator (-80 °C).

All patients underwent standard open radical gastrectomy and lymphonectomy (D2)[4] by the same operators (Huang L, Xu AM, Han WX and Xu J). For those undergoing TG and Roux-en-Y reconstruction, we sealed the duodenal stump with closure device, cut the jejunum 15 cm from the Treitz ligament, performed anastomosis of proximal and distal jejunum with an anastomat 40 cm from the disarticulation place after removing the whole gastric, and cut both vagus nerve trunks. For those undergoing DG with Billroth I reconstruction, we performed jejunogastrostomy with an anastomat after removing the distal part of the stomach and cut the gastric branch of vagus nerve, while the hepatic and celiac ones were preserved. For those undergoing PG plus gastroesophagostomy, the two vagus nerve trunks were also cut during standard removal of proximal part of the stomach.

Information regarding the intra-abdominal findings with special reference to regional and distant metastases was obtained from the surgical reports. Data regarding tumor size, histological type, tumor penetration, and pathological TNM disease stage (based on Japanese classification[13]) were obtained from the pathological records.

Mucosal damage caused by reflux was evaluated by gastroscopy. Reflux symptoms were quantified by both RDQ (with frequency and degree of heartburn, non-cardiac chest pain, acid regurgitation and upwelling of stomach contents recorded and scored, and a diagnostic threshold of 12)[9] and GERD-Q (with frequency and degree of heartburn, acid regurgitation, sleep disturbance, over the counter drugs required, bellyache and nausea recorded and scored, and a diagnostic threshold of 8)[10] scores pre- and 6 mo post-gastrectomy.

We analyzed the data using SPSS 16.0 (Inc. Chicago, IL, United States), comparing means from two identical samples with independent samples t-test, mean of a sample and population mean with one-sample t-test, and means of three different samples with one-way analysis of variance, measuring correlation of 2 groups of normally distributed variables using univariate analysis with Pearson coefficient r calculated, and searching factors affecting target parameters using multiple linear regression with partial regression coefficient b and standardized partial regression coefficient b’ calculated. Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD. The difference was significant with P < 0.05 and very significant with P < 0.01.

The overall pH of all samples before surgery was 4.25 ± 1.45, which is very significantly larger than 3.5, the threshold value of hypoacidity (t = 5.084, P = 0.000). We estimated that the patients with hypoacidity took up 72.73% ± 8.77% of total. No significant difference in pre-operative gastric pH was observed between the 3 groups (4.17 ± 1.63 vs 4.46 ± 1.38 vs 4.07 ± 1.31, F = 0.642, P = 0.529, Figure 1). There were not significant differences between those who smoked and those who did not (4.36 ± 1.52 vs 4.13 ± 1.38, t = 0.786, P = 0.434), or between those who drank and those who did not (4.29 ± 1.49 vs 4.19 ± 1.41, t = 0.332, P = 0.741). Patients suffering from advanced GC had significantly higher gastric juice pH than those with early malignancies (4.49 ± 1.31 vs 3.66 ± 1.61, t = 2.704, P = 0.008).

Patient’s age, tumor size and differentiation grade, and concentrations of gastric juice potassium and bicarbonate ions were factors that significantly influenced gastric pH, while the coefficients of patient’s gender and body mass index, tumor location and TNM classification, and concentrations of gastric juice sodium ion, urea nitrogen, direct and indirect bilirubin, and total bile acid were not statistically significant (Table 2). Sodium ion was positively correlated with urea nitrogen (r = 0.440, P = 0.000).

| b | b’ | t | P value | |

| Gender | -0.062 | -0.020 | -0.270 | 0.788 |

| Age | 0.036 | 0.249 | 2.461 | 0.016c |

| Body mass index | 0.031 | 0.067 | 0.919 | 0.361 |

| Tumor size | 0.132 | 0.176 | 2.401 | 0.019c |

| Tumor location | 0.099 | 0.108 | 1.371 | 0.174 |

| TNM classification | -0.032 | -0.048 | -0.436 | 0.664 |

| Differentiation grade | 0.493 | 0.359 | 2.866 | 0.005d |

| Potassium ion | -0.053 | -0.222 | -2.317 | 0.023c |

| Sodium ion | 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.224 | 0.823 |

| Bicarbonate ion | 0.584 | 0.210 | 2.122 | 0.037c |

| Urea nitrogen | 0.087 | 0.090 | 1.145 | 0.256 |

| Direct bilirubin | -0.244 | -0.030 | -0.440 | 0.661 |

| Indirect bilirubin | 0.254 | 0.108 | 1.347 | 0.182 |

| Total bile acid | 0.051 | 0.043 | 0.582 | 0.562 |

The pH of drainages from the 1st to the 5th days post-gastrectomy in the 3 groups was all very significantly larger than that pre-gastrectomy (P < 0.01 for all, Figure 1). All postsurgical values detected were greater than 4, the lower boundary of cut-off value of weak-acid reflux.

No significant differences existed among all groups with regard to postoperative recovery parameters including time to peri-bed activities (F = 0.138, P = 0.871), borborygmus recurrence (F = 0.235, P = 0.791), flatus duration (F = 2.010, P = 0.140), and degree of pain measured by numerical rating scales (NRS) (F = 0.015, P = 0.985). On the 1st day post-gastrectomy, gastric juice pH was comparable among the 3 groups (6.69 ± 0.94 vs 6.31 ± 0.55 vs 6.68 ± 0.64, F = 2.917, P = 0.059). On the 2nd day, both the TG (6.86 ± 0.67 vs 6.35 ± 0.57, t = 3.399, P = 0.001) and PG (6.74 ± 0.38 vs 6.35 ± 0.57, t = 3.111, P = 0.003) groups were accompanied with significantly higher gastric juice pH than the DG group, while there was not significant difference between the TG and PG groups (t = 0.952, P = 0.345). On days 3-5, situations were similar: patients undergoing TG had significantly higher gastric pH than both individuals receiving DG (day 3: 6.92 ± 0.67 vs 6.49 ± 0.79, t = 2.471, P = 0.016; day 4: 7.35 ± 0.49 vs 6.52 ± 0.75, t = 5.433, P = 0.000; day 5: 7.21 ± 0.56 vs 6.63 ± 0.60, t = 4.139, P = 0.000) and those undergoing PG (day 3: 6.74 ± 0.38 vs 6.56 ± 0.70, t = 2.146, P = 0.036; day 4: 7.35 ± 0.49 vs 6.79 ± 0.44, t = 4.760, P = 0.000; day 5: 7.21 ± 0.56 vs 6.31 ± 0.36, t = 7.732, P = 0.000), while the difference between the DG and PG groups was insignificant (day 3: t = 0.375, P = 0.709; day 4: t = 1.731, P = 0.088; day 5: t = 2.571, P = 0.130) (Figure 1).

The comparison between the 3 groups was the same as those on the 3rd to the 5th days post-operation: the TG group was accompanied with gastric pH significantly higher than that in both the DG (7.34 ± 0.47 vs 6.54 ± 0.58, t = 6.271, P = 0.000) and PG groups (7.34 ± 0.47 vs 6.44 ± 0.38, t = 8.361, P = 0.000), while the DG and PG groups revealed similar results (t = 0.804, P = 0.425) (Figure 1). No significant difference appeared when comparing smokers and nonsmokers (6.78 ± 0.64 vs 6.80 ± 0.63, t = 0.209, P = 0.835), drinkers and nondrinkers (6.68 ± 0.56 vs 6.89 ± 0.68, t = 1.737, P = 0.086), and patients at early and at advanced stages (6.64 ± 0.55 vs 6.86 ± 0.66, t =1.585, P = 0.119).

We did not find any hiatus hernia which might contribute to GERD. Univariate analysis revealed that the older a patient was, the higher concentration of total bilirubin (r = 0.238, P = 0.018) there would be in gastric juice, indicating more serious reflux. RDQ (2.91 ± 1.81 vs 2.65 ± 2.07 vs 2.33 ± 1.71, F = 0.776, P = 0.463) and GERD-Q (1.49 ± 1.15 vs 1.35 ± 1.10 vs 1.37 ± 1.00, F = 0.154, P = 0.857) scores pre-surgery in the 3 groups were both comparable. Six months post-operation, interestingly and not in accordance with the case of gastric juice pH, we found that both the TG and PG groups were accompanied with higher RDQ (TG vs DG: 15.80 ± 5.06 vs 12.26 ± 2.14, t = 3.801, P = 0.000; PG vs DG: 15.37 ± 3.49 vs 12.26 ± 2.14, t = 4.345, P = 0.000) and GERD-Q (TG vs DG: 10.54 ± 3.16 vs 9.15 ± 2.27, t = 2.103, P = 0.039; PG vs DG: 11.00 ± 2.07 vs 9.15 ± 2.27, t = 3.395, P = 0.001) scores compared with the DG group, while the TG and PG groups showed similar scores (RDQ: t = 0.395, P = 0.694; GERD-Q: t = 0.699, P = 0.484).

We further searched factors potentially affecting change in reflux syndrome based on RDQ and GERD-Q scores 6 mo post-surgery compared with those pre-operation, and found that the larger a patient’s body mass index was, the greater change in unfit feeling he/she would experience. As for the gastric juice contents, change in degree of unwell feeling was significantly positively correlated with concentrations of indirect bilirubin and total bile acid, while direct bilirubin played a negative role. Higher level of potassium ion tended to contribute to greater change in discomfort using RDQ scale, but definitely generated greater GERD-Q score change. However, gastric pH was not influential, as well as gender, age, TNM classification, sodium and bicarbonate ions, and urea nitrogen (Table 3). No significant difference was observable between patients at early and at advanced stages (RDQ: 13.87 ± 3.76 vs 14.71 ± 4.20, t = 0.947, P = 0.346; GERD-Q: 9.80 ± 2.61 vs 10.38 ± 2.69, t = 0.991, P = 0.324).

| Scale | b | b’ | t | P value | |

| Gender | RDQ | -1.342 | -0.139 | -1.393 | 0.167 |

| GERD-Q | -0.604 | -0.098 | -1.046 | 0.299 | |

| Age | RDQ | 0.072 | 0.160 | 1.506 | 0.136 |

| GERD-Q | 0.056 | 0.194 | 1.952 | 0.054 | |

| Body mass index | RDQ | 0.339 | 0.265 | 2.629 | 0.010c |

| GERD-Q | 0.227 | 0.277 | 2.939 | 0.004d | |

| TNM classification | RDQ | -0.119 | -0.059 | -0.546 | 0.587 |

| GERD-Q | -0.014 | -0.011 | -0.108 | 0.914 | |

| pH | RDQ | 0.121 | 0.017 | 0.17 | 0.865 |

| GERD-Q | -0.142 | -0.031 | -0.331 | 0.741 | |

| Potassium ion | RDQ | 0.079 | 0.155 | 1.295 | 0.099 |

| GERD-Q | 0.074 | 0.227 | 2.025 | 0.046c | |

| Sodium ion | RDQ | 0.017 | 0.117 | 1.137 | 0.259 |

| GERD-Q | 0.013 | 0.136 | 1.417 | 0.160 | |

| Bicarbonate ion | RDQ | 0.381 | 0.198 | 2.019 | 0.147 |

| GERD-Q | 0.192 | 0.156 | 1.701 | 0.193 | |

| Urea nitrogen | RDQ | -0.074 | -0.087 | -0.781 | 0.437 |

| GERD-Q | -0.070 | -0.129 | -1.242 | 0.218 | |

| Direct bilirubin | RDQ | -0.985 | -0.374 | -2.970 | 0.004d |

| GERD-Q | -0.704 | -0.416 | -3.542 | 0.001d | |

| Indirect bilirubin | RDQ | 0.077 | 0.252 | 2.251 | 0.027c |

| GERD-Q | 0.073 | 0.374 | 3.585 | 0.001d | |

| Total bile acid | RDQ | 0.005 | 0.178 | 1.517 | 0.033c |

| GERD-Q | 0.005 | 0.272 | 2.485 | 0.015c |

All detected gastric juice contents significantly rose post-gastrectomy compared with those pre-operation (sodium ion: 102.22 ± 30.70 vs 63.34 ± 29.64, t = 11.791, P = 0.000; bicarbonate ion: 3.75 ± 2.32 vs 1.14 ± 0.52, t = 7.227, P = 0.000; urea nitrogen: 9.07 ± 5.26 vs 4.27 ± 1.51, t = 6.145, P = 0.000; direct bilirubin: 1.49 ± 1.69 vs 0.16 ± 0.18, t = 3.724, P = 0.000; indirect bilirubin: 18.03 ± 14.53 vs 0.58 ± 0.61, t = 4.832, P = 0.000; total bile acid: 209.65 ± 149.76 vs 2.55 ± 1.22, t = 11.036, P = 0.000), except potassium ion (15.29 ± 8.74 vs 14.12 ± 6.09, t = 1.379, P = 0.171) (Table 4). Gastric juice potassium ion was significantly negatively correlated with sodium ion (r = -0.233, P = 0.020), which was positively correlated with bicarbonate ion (r = 0.210, P = 0.037); direct bilirubin was positively correlated with indirect bilirubin (r = 0.438, P = 0.000); and total bilirubin post-gastrectomy was significantly correlated with total bile acid (r = 0.400, P = 0.000).

| Gastric juice content | Way of gastrectomy | Pre-gastrectomy | Six months post-gastrectomy |

| Potassium ion (mmol/L) | TG | 11.77 ± 4.41 | 16.54 ± 11.80 |

| DG | 14.18 ± 5.70 | 12.65 ± 5.90 | |

| PG | 16.80 ± 7.17 | 16.80 ± 6.55 | |

| Sodium ion (mmol/L) | TG | 56.16 ± 34.09 | 111.68 ± 36.06 |

| DG | 78.68 ± 21.71 | 104.10 ± 23.27 | |

| PG | 54.32 ± 25.44 | 89.06 ± 27.44 | |

| Bicarbonate ion (mmol/L) | TG | 1.05 ± 0.52 | 4.36 ± 2.51 |

| DG | 1.19 ± 0.47 | 3.28 ± 2.09 | |

| PG | 1.19 ± 0.58 | 3.58 ± 2.25 | |

| Urea nitrogen (mmol/L) | TG | 3.63 ± 0.83 | 10.60 ± 6.00 |

| DG | 4.80 ± 1.58 | 9.74 ± 4.83 | |

| PG | 4.42 ± 1.80 | 7.17 ± 4.39 | |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L) | TG | 0.17 ± 0.16 | 0.87 ± 1.40 |

| DG | 0.14 ± 0.17 | 2.20 ± 1.92 | |

| PG | 0.16 ± 0.21 | 1.39 ± 1.43 | |

| Indirect bilirubin (μmol/L) | TG | 0.49 ± 0.55 | 13.61 ± 12.74 |

| DG | 0.64 ± 0.65 | 17.85 ± 11.91 | |

| PG | 0.61 ± 0.65 | 23.41 ± 17.56 | |

| Total bile acid (μmol/L) | TG | 1.98 ± 1.32 | 187.13 ± 199.14 |

| DG | 3.00 ± 1.08 | 212.94 ± 103.39 | |

| PG | 2.73 ± 1.00 | 232.21 ± 126.40 |

We used to further alkalify gastric juice, hoping to relieve reflux symptoms like heartburn among GC patients, regardless of the completeness of the stomach[4-7]. Patients treated usually take drugs like PPIs and/or H2 receptor blocking agents, hoping to relieve their reflux symptoms pre- and post-gastrectomy, which causes the usage of acid-suppressive drugs to increase obviously without definite indications, and increases the rate of indigestion and the cost of health care[14]. However, whether it is proper to increase gastrointestinal pH has long been discussed and remains controversial[14-17]. Since former studies on acid-suppression were mainly focused on patients with an intact stomach[18-20], our study which is concentrated on the peri-operative gastrointestinal contents and acidity and aims at uncovering whether it is proper to suppress acid with the stomach removed may be novel and valuable in providing direct evidence for front-line gastroenterologists to make wise decisions.

Gastric juice is liquid in the stomach, containing hydrochloric acid, which is strong and produced by the parietal cells in the corpus, generating gastric pH of 2-3, pepsin, electrolytes, bile due to reflux, etc. When the pH exceeds 3.5, we call it hypoacidity[21,22]. According to our study, pre-operative pH in 99 patients was basically of hypochlorhydria, and advanced GC was associated with higher gastric pH, which is in accordance with a histological report showing that atrophic mucosa with low acid secretion exists in 80%-90% of patients with GC[23]. In this case, pathogenic microorganisms may escape the preventive mechanism, causing more diarrheas, and activating the carcinogenic process again with more N-nitroso compounds generated[24]. Also, it may lead to esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in the long run[25], and if we further alkalify the gastrointestinal juice, the situation may get worse. We further found that the older a patient was, the larger the tumor was, the more poorly the malignancy differentiated, and the more bicarbonate ion there was in gastric juice, the higher gastric pH there would be, while higher potassium ion concentration contributed to greater acidity.

We performed standard jejunal Roux-en-Y reconstruction, gastroduodenostomy in the Billroth I way and esophagogastrostomy after TG, DG and PG, respectively, for they are the commonly used reconstructive methods, when taking benefits and disadvantages concerned with post-surgical QOL and prognosis in the long run into account comprehensively[2,3]. After gastrectomy, with the breakdown of physiological anti-reflux barrier, reflux exists in diverse degrees. Our study revealed that all detected gastric contents including sodium and bicarbonate ions, urea nitrogen, direct and indirect bilirubin and total bile acid significantly rose post-gastrectomy, except potassium ion. After the distal part of the stomach is removed, secretion of acid weakens as parietal and G cells decrease and neural stimulating effects weaken. Delayed emptying of the remnant stomach, antiperistalsis of the intestine due to destruction of “Crow’s foot” of vagus nerve, and the dysfunction of the low esophageal sphincter (LES) cause more reflux to emerge. After PG, with cardiac sphincter removed, cavity of the remnant stomach shifts position or becomes narrower, leading to malfunction of storage and emptying. Neural influences disappear completely after both vagus nerve trunks are cut off. The function of the pylorus weakens due to being dragged and losing control of nerves. Thus acidity inside the remnant gastric decreases greatly. Besides, in both cases, the stimulation and stress reaction of surgical and emotional factors also contribute to the increase of pH inside the remnant gastric. Obviously, different post-resection reconstructions might result in discrepant gastric contents.

Gastrointestinal reflux post-surgery can be divided into acid reflux (AR, with pH of reflux content < 4), weak AR (WAR, with pH of reflux content = 4-7) and none-AR (NAR, with pH of reflux content > 7)[21]. Studies have shown that duodenogastric reflux contents are the same as those entering the esophagus, and that the acidity of contents entering the lower esophagus is in accordance with that inside the stomach[26,27], so the acidity of drainage we collected through the gastric tube can basically stand for or is even more basic than the reflux juice contacting the esophagus. In our study, we found that gastrointestinal juice significantly rose and was all in weak- or non-acidity state post TG, DG and PG. With early activities out of bed, the effects of anesthesia, stress, and psychological factors die away. With the recovery of gastrointestinal motility, rectification of internal environment and stabilization of neurohormonal factors, the acidity inside the remnant digestive tract reaches a relatively steady condition gradually. Our results proved that gastric pH 6 mo post-surgery was basically the same as that on the 3rd to the 5th days post-operation in fasting state, suggesting a steady interval between them. After exposure to diet, due to the buffering and evacuation effects of food, patients may have more basic juice[3]. We further found that acidity did not play a significant role in causing reflux symptom change. Higher gastric pH will increase solubility of bile salts. Our multivariate analysis revealed that indirect bilirubin and total bile acid contributed to greater change in symptom, while direct bilirubin seemed to be protective. Studies reported that direct bilirubin was lipophilic, and could effectively reduce cell oxidative toxicity, while hydrophilic substances like indirect bilirubin and total bile acid might strengthen the damage[28]. There is evidence showing that reflux fluid mixed with intestinal juice does more harm than pure acid, damage caused by which may be induced by immune factors, rather than direct oxidation of acid, which might even suppress the toxicity of other reflux contents[29]. Furthermore, with pH > 4 post-gastrectomy supported by our study, pepsin whose fittest pH is 1.8 will degenerate and weaken in function[12]. Besides, we only have to make the gastric pH larger than 4 if we want to heal reflux esophagitis, and stress ulcer usually occurs with pH lower than 4[30]. Moreover, in the circumstance with pH > 4 post-operation according to our research, clearance of PPI which is weak basic will significantly accelerate, and its function will quickly weaken, disappear or even reverse[31]. In addition, with gastric pH > 4 in accordance with our study, solubility of most new oral anti-carcinoma and molecular targeting drugs decreases significantly and interactions between them intensify. If we further increase pH inside the stomach, the situation may become worse[32].

After gastrectomy, our finding also suggested that larger body mass index resulted in greater change in unfit feeling caused by reflux. Interestingly, higher potassium ion level also contributed to greater GERD-Q score change, while gender, age, TNM classification, sodium and bicarbonate ions, and urea nitrogen were not influential. Both vagus nerve trunks or the gastric brunch of the nerve were cut off during gastrectomy, and this leads to a potential change in gastric emptying after operation, which might also contribute to GERD symptoms. However, we have not got any data available to suggest the influence of this factor in our study. The bivariate correlations between potassium, sodium and bicarbonate ions aroused our interest, and we are further working on it, hoping to uncover the mechanism.

Still, further study is needed to uncover whether acid suppression will cause more terrible discomfort and potential disastrous consequences than non-acid suppression post gastrectomy in the long run, and we are keeping track of the patients studied. Also, we need to further analyze the potential function of reflux contents and maybe we should transfer our attention to other possible damaging factors like bile acid and bilirubin rather than acidity, and change in eating habits and contents in order to improve our patients’ post-gastrectomy QOL and prognosis.

This study is mainly limited by the original method for collecting gastrointestinal juice applied, the specific surgical approaches conducted, neglect of the influence of a potential change in gastric emptying due to vagus nerve blocking on GERD symptoms after gastrectomy, and the fact that this is mainly a symptom study while the pathological data of successive diseases related to reflux including esophagitis were not available in analysis.

In conclusion, patients with gastric cancer suffer from weak- or non-AR post-surgery, and acidity is not an important factor causing discomfort among them. It is not a wise choice to further decrease gastric acidity both pre- and post-gastrectomy.

We thank Colleges of Basic Medicine and Public Hygiene in Anhui Medical University, and Department of Clinical Laboratory and the Information Center in the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University for their contributions to our study.

Gastric carcinoma (GC) remains one of the most common malignancies and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Surgery is the major treatment, which includes total gastrectomy (TG), distal gastrectomy (DG) and proximal gastrectomy (PG).

With the advancement in gastrointestinal operation and the improvement of the comprehensive methods to treat cancer, patients undergoing gastrectomy can enjoy a longer life, leading to their growing focus on the post-surgical quality of life (QOL). Nowadays gastroenterologists are trying harder to reduce complications and improve QOL after patients’ stomach is removed.

The authors found that gastrointestinal juice significantly rose and was all in weak- or non-acidity state post TG, DG and PG.

Patients with gastric cancer suffer from weak- or non-acid reflux post-surgery, and acidity is not an important factor causing discomfort among them. It is not a wise choice to further decrease gastric acidity both pre- and post-gastrectomy.

The study is about the changes in gastric acidity encountered before and after gastric surgery for carcinoma. It is well planned and written.

P- Reviewers: Boyacioglu AS, Okada H, Park KU S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25541] [Article Influence: 1824.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9215] [Cited by in RCA: 9856] [Article Influence: 821.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, Knijn A, Marchesi F, Capocaccia R. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995-1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:931-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 645] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 38.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1140] [Cited by in RCA: 1308] [Article Influence: 87.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Katz PO, Zavala S. Proton pump inhibitors in the management of GERD. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14 Suppl 1:S62-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cicala M, Emerenziani S, Caviglia R, Guarino MP, Vavassori P, Ribolsi M, Carotti S, Petitti T, Pallone F. Intra-oesophageal distribution and perception of acid reflux in patients with non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:605-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Katz PO, Ginsberg GG, Hoyle PE, Sostek MB, Monyak JT, Silberg DG. Relationship between intragastric acid control and healing status in the treatment of moderate to severe erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:617-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Azatian A, Yu H, Dai W, Schneiders FI, Botelho NK, Lord RV. Effectiveness of HSV-tk suicide gene therapy driven by the Grp78 stress-inducible promoter in esophagogastric junction and gastric adenocarcinomas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1044-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kahrilas PJ, Jonsson A, Denison H, Wernersson B, Hughes N, Howden CW. Concomitant symptoms itemized in the Reflux Disease Questionnaire are associated with attenuated heartburn response to acid suppression. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1354-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jonasson C, Wernersson B, Hoff DA, Hatlebakk JG. Validation of the GerdQ questionnaire for the diagnosis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:564-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morris K. Revising the Declaration of Helsinki. Lancet. 2013;381:1889-1890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chae HD, Kim IH, Lee GH, Shin IH, Suh HS, Jeon CH. Gastric cancer detection using gastric juice pepsinogen and melanoma-associated gene RNA. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Loffeld RJ, van der Putten AB. Rising incidence of reflux oesophagitis in patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Digestion. 2003;68:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hatlebakk JG, Hyggen A, Madsen PH, Walle PO, Schulz T, Mowinckel P, Bernklev T, Berstad A. Heartburn treatment in primary care: randomised, double blind study for 8 weeks. BMJ. 1999;319:550-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Theisen J, Peters JH, Stein HJ. Experimental evidence for mutagenic potential of duodenogastric juice on Barrett’s esophagus. World J Surg. 2003;27:1018-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Orel R, Vidmar G. Do acid and bile reflux into the esophagus simultaneously? Temporal relationship between duodenogastro-esophageal reflux and esophageal pH. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Poulsen AH, Christensen S, McLaughlin JK, Thomsen RW, Sørensen HT, Olsen JH, Friis S. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1503-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bashford JN, Norwood J, Chapman SR. Why are patients prescribed proton pump inhibitors? Retrospective analysis of link between morbidity and prescribing in the General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 1998;317:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Reimer C, Bytzer P. Discontinuation of long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy in primary care patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in patients with symptom relapse. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1182-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schubert ML. Gastric secretion. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:598-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Callender ST, Retief FP, Witts LJ. The augmented histamine test with special reference to achlorhydria. Gut. 1960;1:326-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim N, Park YS, Cho SI, Lee HS, Choe G, Kim IW, Won YD, Park JH, Kim JS, Jung HC. Prevalence and risk factors of atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in a Korean population without significant gastroduodenal disease. Helicobacter. 2008;13:245-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bavishi C, Dupont HL. Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1269-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Iijima K, Koike T, Abe Y, Yamagishi H, Ara N, Asanuma K, Uno K, Imatani A, Nakaya N, Ohara S. Gastric hyposecretion in esophageal squamous-cell carcinomas. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1349-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hemmink GJ, Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Monkelbaan JF, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Esophageal pH-impedance monitoring in patients with therapy-resistant reflux symptoms: ‘on’ or ‘off’ proton pump inhibitor? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2446-2453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fein M, Maroske J, Fuchs KH. Importance of duodenogastric reflux in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Br J Surg. 2006;93:1475-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Thao TD, Ryu HC, Yoo SH, Rhee DK. Antibacterial and anti-atrophic effects of a highly soluble, acid stable UDCA formula in Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:2135-2146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Souza RF, Huo X, Mittal V, Schuler CM, Carmack SW, Zhang HY, Zhang X, Yu C, Hormi-Carver K, Genta RM. Gastroesophageal reflux might cause esophagitis through a cytokine-mediated mechanism rather than caustic acid injury. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1776-1784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Johnson DA, Katz PO, Levine D, Röhss K, Astrand M, Junghard O, Nagy P. Prevention of relapse of healed reflux esophagitis is related to the duration of intragastric pH & gt; 4. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:475-478. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Armstrong D, Talley NJ, Lauritsen K, Moum B, Lind T, Tunturi-Hihnala H, Venables T, Green J, Bigard MA, Mössner J. The role of acid suppression in patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease: the effect of treatment with esomeprazole or omeprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:413-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Budha NR, Frymoyer A, Smelick GS, Jin JY, Yago MR, Dresser MJ, Holden SN, Benet LZ, Ware JA. Drug absorption interactions between oral targeted anticancer agents and PPIs: is pH-dependent solubility the Achilles heel of targeted therapy? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:203-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |