Published online Jun 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6939

Revised: February 7, 2014

Accepted: March 4, 2014

Published online: June 14, 2014

Processing time: 232 Days and 5 Hours

AIM: To investigate the clinical characteristics, surgical strategies and prognosis of solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPTs) of the pancreas in male patients.

METHODS: From July 2003 to March 2013, 116 patients were diagnosed with SPT of the pancreas in our institution. Of these patients, 16 were male. The patients were divided into two groups based on gender: female (group 1) and male (group 2). The groups were compared with regard to demographic characteristics, clinical presentations, surgical strategies, complications and follow-up outcomes.

RESULTS: Male patients were older than female patients (43.1 ± 12.3 years vs 33.1 ± 11.5 years, P = 0.04). Tumor size, location, and symptoms were comparable between the two groups. All patients, with the exception of one, underwent complete surgical resection. The patients were regularly followed up. The mean follow-up period was 58 mo. Two female patients (1.7%) developed tumor recurrence or metastases and required a second resection, and two female patients (1.7%) died during the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION: Male patients with SPT of the pancreas are older than female patients. There are no significant differences between male and female patients regarding surgical strategies and prognosis.

Core tip: Solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas is a rare tumor, with low-grade malignancy and a strong female preponderance. Male patients have been shown to have distinct patterns of onset and aggressiveness compared with female patients. However, this finding is controversial. This study included the largest number of male patients with SPT of the pancreas from a single institution and provided a better understanding of SPT in male patients.

- Citation: Cai YQ, Xie SM, Ran X, Wang X, Mai G, Liu XB. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in male patients: Report of 16 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(22): 6939-6945

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i22/6939.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i22.6939

Solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas was first reported by Frantz[1] in 1959. SPT is a rare pancreatic tumor, accounting for approximately 1%-3% of pancreatic neoplasms, and has low-grade malignancy and a strong female preponderance[2,3]. Less than 10% of patients with SPT in the reported literature were male[4]. Complete surgical resection of SPT can achieve a favorable prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate higher than 95%[5].

Male patients have been shown to have distinct patterns of onset and aggressiveness compared with female patients. However, this finding is controversial. Machado et al[3] stated that SPTs in male patients were more aggressive than those in female patients and should be treated more radically. In the present study, we included 116 cases of SPT from a single institution. Of these patients, 16 were male. To our knowledge, our series included the largest number of male patients with SPT from a single institution, and provided a better understanding of SPT in male patients.

From July 2003 to March 2013, 116 patients were diagnosed with SPT of the pancreas at our hospital based on histopathological examination. These patients were divided into two groups based on gender: female (group 1, 100 cases) and male (group 2, 16 cases). All patients were consecutively enrolled into the present study. Following surgery, all patients were followed-up in the outpatient department or via telephone interviews. Data were collected retrospectively by chart review and included demographic characteristics, clinical presentations, surgical strategies, post-operative details and follow-up outcomes. Pancreatic fistula was defined as the Johns Hopkins Hospital and the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula[6]. Overall morbidity was defined as total complications occurred from the day of operation to post-operative day 30. Mortality was defined as the number of patients who died from any cause, directly or indirectly related to operation from the day of operation to post-operative day 30. Written consent was obtained from the patients included in this study, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sichuan University.

Tumor samples were sent to the pathology department of our institution for histopathological examination and selected samples were sent for immunohistochemical examination. The diagnosis of SPT of the pancreas was made by two pathology specialists.

Numerical data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows. Differences between variables were compared using the Student’s t test, the χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The demographic characteristics of the patients included in this study are shown in Table 1. There were 100 female patients and 16 male patients, with a female to male ratio of 6.25 to 1. The mean age of these patients at diagnosis was 35 years (range, 13-68 years). Male patients were older than female patients (43.1 ± 12.3 years vs 33.1 ± 11.5 years, P = 0.04). The oldest patient in our series was a 68-year-old man. The mean diameter of the tumors was 6.3 cm (range, 1-25 cm). On average, male patients had smaller SPTs than female patients (5.8 ± 2.0 cm vs 6.5 ± 3.5 cm), however, this difference was not significant.

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | P value |

| Cases | 100 | 16 | - |

| Age (yr) | 33.1 ± 11.5 | 43.1 ± 12.3 | 0.043 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 6.5 ± 3.5 | 5.8 ± 2.0 | NS |

| Symptoms | NS | ||

| Abdominal pain | 41 (41) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 17 (17) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Palpable abdominal mass | 17 (17) | 0 | |

| No symptoms | 24 (24) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Jaundice | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Location of tumors | NS | ||

| Head | 31 (31) | 7 (43.7) | |

| Neck | 21 (21) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Body and Tail | 6 (6) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Tail | 37 (37) | 5 (31.3) | |

| The uncinate process | 4 (4) | 0 | |

| Head and tail | 1 (1) | 0 |

Overall, 84 patients (72.4%) were symptomatic, including abdominal pain (47 cases, 40.5%), abdominal discomfort (19 cases, 16.4%), palpable abdominal mass (17 cases, 14.7%), and jaundice (1 case, 0.9%). Thirty-two patients were asymptomatic. They were diagnosed with a pancreatic neoplasm by routine examination using ultrasonography or computed tomography. Compared with female patients, a higher proportion of male patients were asymptomatic (8 cases, 50%). The most frequent location of SPT in male patients was the pancreatic head (7 cases, 43.7%), followed by the pancreatic tail (5 cases, 31.3%), and the pancreatic neck (2 cases, 12.5%). Tumor locations were comparable between male and female patients.

The surgical details of the patients included in this study are shown in Table 2. In male patients, we performed 6 non-radical operations, including 2 cases of middle pancreatectomy, 2 cases of distal pancreatectomy with spleen preservation, and 2 cases of enucleation. For the other ten male patients, we performed radical operations, including 5 cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy, and 5 cases of distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. In female patients, non-radical operations were carried out in 46 of 100 patients, including 13 cases of middle pancreatectomy, 17 cases of distal pancreatectomy with spleen preservation, and 16 cases of enucleation. The other 53 patients had more radical operations, including 29 cases of pancreaticoduodenectomy and 23 cases of distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. There was one female patient suffered from simultaneous pancreatic head and tail SPT. Enucleation of pancreatic head lesion and distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy of pancreatic tail lesion was carried out. We performed tumor fine-needle biopsy and cholangiojejunostomy in a patient with a 9-cm SPT in the pancreatic head, due to extensive portal vein and superior mesenteric vein involvement and multiple liver metastases. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of organ-preservation rate (46% vs 37.5%, P = 0.526).

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | P value |

| (n = 100) | (n = 16) | ||

| Surgical strategies | NS | ||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 29 (29) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Middle pancreatectomy | 13 (13) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 17 (17) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy | 23 (23) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Enucleation | 16 (16) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Enucleation + distal pancreatectomy | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Cholangiojejunostomy without tumor resection | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Organ-preserving operation | 46 (46) | 6 (37.5) | NS |

| Vessel involvement and metastases | |||

| Vessel involvement | 29 (29) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Pancreatic tissue infiltration | 6 (6) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Adjacent organs compromised | 2 (2) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Liver metastases | 5 (5) | 0 | |

| Total | 31 (31) | 4 (25) | NS |

The operative time and the estimated blood loss differed due to surgical strategies and tumor size. The median operative time was 235 min (range, 155-420 min). The median estimated blood loss was 320 mL (range, 50-1500 mL). There was no perioperative mortality. Post-operative complications are shown in Table 3. The overall complication rate was 19.1% (n = 22). Two patients (12.5%) in group 2 developed pancreatic fistulae, which were resolved by conservative therapy. Twenty patients (20%) in group 1 developed complications, including 11 cases of pancreatic fistula, 3 cases of pulmonary infection, 3 cases of fluid collection in the abdominal cavity, 2 cases of incision infection, and 1 case of alimentary tract hemorrhage. Six patients with a pancreatic fistula required percutaneous drainage; the other 5 patients underwent successful conservative therapy. The patient who developed alimentary tract hemorrhage required emergency laparotomy to stop the bleeding. She was discharged on the 8th postoperative day after the second surgery. However, the patient experienced abdominal pain and was diagnosed with abdominal infection one month after discharge. This was resolved by percutaneous drainage and antibiotics. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of post-operative complications.

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | P value |

| (n = 100) | (n = 16) | ||

| Complications | |||

| Pancreatic fistula | 11(11) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Incision infection | 2 (2) | 0 | |

| Fluid collection in abdomen | 3 (3) | 0 | |

| Pulmonary infection | 3 (3) | 0 | |

| Alimentary tract hemorrhage | 1 (1) | 0 | |

| Total | 20 (20) | 2 (12.5) | NS |

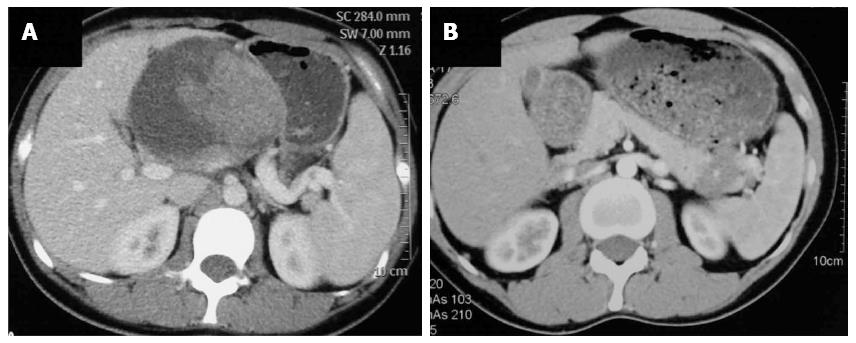

Preoperative radiological examinations, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), were routinely performed. Typical appearance of the pancreatic SPT on CT was a well-circumscribed cystic and solid mass with heterogeneous enhancement (Figure 1A). Calcification of the mass may also be present; however, pancreatic duct dilatation or parenchymal atrophy is rare. Eighteen cases (15.5%) of SPT in our series showed calcification on CT images. Dilation of the bile duct or pancreatic duct was very rare. Only three cases (2.6%) of SPT showed dilation of the bile duct or pancreatic duct. However, for SPTs smaller than 3 cm, the cystic portion of the tumor may not be apparent. It may appear as a solid mass with a sharp margin and with weak enhancement during the pancreatic phase (Figure 1B). MRI, with superior contrast resolution, displayed intratumoral hemorrhage and the capsule of the SPT better than CT[7]. The typical appearance of SPT on MRI examination was a well encapsulated lesion with heterogeneous high or low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and early peripheral heterogeneous enhancement on gadolinium-enhanced dynamic MRI. Spotty areas of high intensity which suggested hemorrhagic degeneration were constantly detected on fat-suppressed T1-weighted images[8].

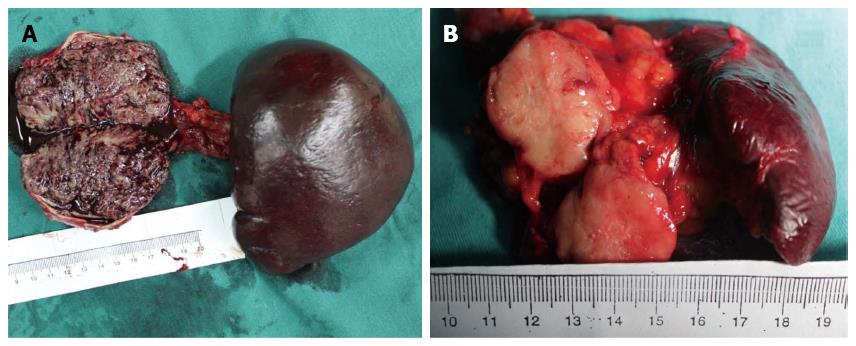

The gross appearance of SPT depends to some extent on the size of the tumor. The typical appearance of SPT was a well capsulated and well demarcated tumor, with a combination of solid, pseudopapillary, or hemorrhagic components in various proportions (Figure 2A). However, smaller tumors may be less likely to have cystic changes, and often appeared as an uncapsulated, solid mass (Figure 2B).

Microscopically, the histologic appearance of SPT was remarkably uniform. The typical microscopic appearance of the solid area of SPT was a uniform poorly cohesive area of polygonal cells surrounding delicate blood vessels. On immunohistochemical examination, the neoplastic cells were typically positive for β-catenin and vimentin in all tumors, and most expressed α1-antitrypsin, CD56, CD10, and neuron specific enolase. No differences in immunohistochemical staining or in pathologic characteristics were found to be attributable to gender alone.

Pathologically, SPT is considered malignant if it manifests pancreatic parenchymal infiltration, extrapancreatic involvement, perineural or vascular infiltration, or metastases[9]. In group 1, 31 patients (31%) manifested at least one of the biological behaviors listed above. Four patients (25%) had malignant SPT. No significant difference between the two groups regarding the proportion of malignant SPTs was observed.

The results of a comparison between benign and malignant SPTs are shown in Table 4. There were no significant differences between benign and malignant SPTs with regard to gender, age, and location of the tumors. The mean tumor size was larger in the malignant group (7.6 ± 3.7 cm vs 4.5 ± 1.9 cm, P = 0.035). Thirty SPTs in the malignant group were larger than 5 cm. SPTs larger than 5 cm were more likely to be malignant tumors (P = 0.001).

| Variables | Benign SPT | Malignant SPT | P value |

| (n = 81) | (n = 35) | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 12/69 | 4/31 | NS |

| Age (yr) | 36.4 ± 3.3 | 31.8 ± 5.9 | NS |

| Tumor size | 0.001 | ||

| < 5 cm | 38 (46.9) | 5 (14.3) | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 43 (53.1) | 30 (86.7) | |

| Mean tumor size | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 7.6 ± 3.7 | 0.035 |

| Location of SPT | NS | ||

| Head | 28 (34.7) | 10 (28.6) | |

| Neck | 19 (23.4) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Body and tail | 4 (4.9) | 4 (11.4) | |

| Tail | 26 (32.1) | 16 (45.7) | |

| The uncinate process | 4 (4.9) | 0 | |

| Multiple locations | 0 | 1 (2.9) |

All patients were regularly followed-up every six months or yearly after surgery. The follow-up data were collected by telephone interview or outpatient department interview. The mean follow-up period was 58 mo (range, 6-121 mo). None of the patients in group 2 experienced tumor recurrence or metastases. However, two patients (2%) in group 1 developed tumor recurrence or metastases, respectively. One patient in group 1 had SPT in the pancreatic body and underwent distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy. On histological examination, the tumor manifested pancreatic parenchymal infiltration, perineural and vascular infiltration. The patient developed local recurrence three months after surgery and underwent a second laparotomy. This patient was followed for 21 mo and did not show recurrence. Another patient developed isolated liver metastases 11 mo after the first surgery and underwent resection of the liver metastases, resulting in a 38-month tumor-free period. Two patients in group 1 died during the follow-up period, including one patient with a 25-cm SPT which was resected, who died of arrhythmia three months after surgery, and a patient whose tumor was unresectable and died of liver failure 18 mos after surgery. There were no local recurrences or metastases in the remaining patients. No significant differences between the two groups regarding the follow-up outcomes were observed.

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas is an uncommon neoplasm, which was first reported by Frantz in 1959 and was described as a new entity with solid and cystic components. Over time, this tumor has been reported to have different names, such as solid and papillary tumor, solid-cystic tumor, papillary cystic tumor, and solid and papillary epithelial neoplasm. In 1996, it was defined by the World Health Organization as a “solid pseudopapillary tumor” of the pancreas, which described the two major histological features of the tumor: solid and papillary components[10].

Due to the rarity of SPT, especially in male patients, there are few data available in the literature regarding the differences between male and female patients. Machado et al[3] performed a retrospective study which included 27 female patients and 7 male patients with SPT of the pancreas. They reported that male patients with SPT had distinct patterns of onset and aggressiveness compared with female patients and would be best treated by more radical surgery. Tien et al[11] compared the immunohistological staining patterns and presence of sex hormone receptors in 4 male and 11 female patients, and demonstrated that there were no differences in the expression of sex hormone receptor protein or clinicopathologic characteristics between male and female patients. However, due to limited sample size, it was difficult to determine if differences were definite or incidental. The present study included the largest sample size of male SPT patients to date, and allowed us to establish a more definite conclusion.

Different from other pancreatic tumors, SPTs have unique epidemiological characteristics[12]. They mainly affect young women in the third or fourth decade of life. Due to their rarity, clinical data on SPTs in male patients are scarce in the literature. In general, the clinical presentations of a SPT are usually unspecific. The most frequent symptoms of SPT in our series, which were abdominal pain, followed by abdominal discomfort, may be the result of compression of the tumor. Jaundice is a very rare symptom of SPT, even in cases with large tumors located in the pancreatic head and involving the common bile duct. In our series, male patients were older than female patients, with an average age of 43.1 years, and more male patients were asymptomatic. The other clinical presentations of SPT were not significantly different between the two groups.

SPT is difficult to accurately diagnose preoperatively[13]. As surgeons have become better able to recognize this neoplasm, there has been a steady increase in the number of SPTs. With a better understanding of its epidemiological characteristics, clinical presentations and radiological appearances, it is possible to diagnose this rare neoplasm preoperatively. The radiological appearance of SPT is unique. Computed tomography can show a heterogeneous mass, with a combination of solid and cystic components in various proportions. However, it is more difficult to diagnose SPT when the tumor is smaller than 3-cm in diameter. For SPTs smaller than 3-cm, the cystic component may not be obvious. SPTs may appear as solid tumors with a sharp margin, weak enhancement during the pancreatic phase and a gradually increasing enhancement pattern[14]. Magnetic resonance imaging can display the capsule and intratumoral hemorrhage better than CT[15]. Tumor markers, such as carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen, are always normal in patients with SPT. Only two patients (1.7%) in our series had slight elevation of carbohydrate antigen 19-9. Percutaneous or endoscopic fine-needle aspiration may be helpful in establishing an accurate preoperative diagnosis[16,17]. However, the utility of this procedure in patients with suspected SPT may be contraindicated because this procedure may cause tumor cell dissemination[18]. Kim et al[19] stated that radiologic diagnosis is sufficient for SPT, especially when planning surgery. To date, most SPTs have been diagnosed based on their gross and microscopic appearance. For SPTs which are difficult to diagnose morphologically, immunohistochemical staining is useful. Most SPTs express nuclear β-catenin, but do not express E-cadherin[20]. Beta-catenin is a useful biomarker to differentiate SPT from endocrine tumors of the pancreas, which strongly express E-cadherin, but do not express β-catenin. Overall, a diagnosis of SPT should be strongly suspected in young female patients or older male patients, with typical radiological appearance and a normal level of carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Complete surgical resection (R0) is the most effective therapy for SPT[21]. Pancreatoduodenectomy, distal pancreatectomy (with or without splenectomy), middle pancreatectomy, or enucleation can be performed based on the location, size, angioinvasion, and adjacent organ compromise. A classic or pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy is indicated in cases with tumors located in the pancreatic head or uncinate process. Given the excellent prognosis, in patients with SPTs which involve the superior mesenteric vein or/and portal vein, vein resection and reconstruction should be considered. Distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy can be performed for tumors located in the pancreatic body or tail. For patients with tumors located in the neck or body of the pancreas, without vessel involvement, we prefer to perform middle pancreatectomy with distal pancreatojejunostomy, preserving the rim of the head, the uncinate process, and the tail portion. Due to the low grade of malignancy and the dense fibrous capsule of SPT, enucleation is feasible for smaller tumors which are distant from the main pancreatic duct, without impairing long-term survival. The incidence of lymph node metastasis is extremely rare. None of the patients in our series developed lymph node metastases. Routine radical lymphadenectomy is not recommended in patients with SPT[19]. Tumors with vessel involvement or metastases do not indicate unresectability[9]. Sperti et al[4] reported 17 patients who underwent vascular resection and reconstruction without mortality. All patients, except one, with malignant SPT underwent complete resection of the tumor. The patients included in our study who underwent surgical resection achieved good long-term survival during the follow-up period.

SPT is considered to be malignant if it manifests pancreatic parenchymal infiltration, extrapancreatic involvement, perineural or vascular infiltration, or metastases. Approximately 15% to 20% of cases in the reported literature manifested malignant behavior[22,23]. The liver is the most common site of metastasis[24]. Simultaneous multiple SPTs were rarely reported in the literature. There was only one female patient who suffered from multiple SPTs. The multiple SPTs were successfully resected. This patient has been followed for 38 mo and she did not suffer from tumor recurrence. Some studies have reported a correlation between tumor size (> 5 cm), tumor necrosis, male sex, and SPTs with malignant potential[25]. However, other studies have indicated that gender, age, tumor size, tumor location, and increased tumor markers were not associated with the malignant potential of SPTs[26]. There were 35 cases (30.1%) of malignant SPT in our series, including 31 female patients and 4 male patients. We found that age, gender, and tumor location were not associated with the malignant potential of SPT; however, tumor size was associated with malignancy. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the proportion of malignant SPTs and follow-up outcomes.

However, there were some limitations associated with this study. It was a retrospective cohort study from a single institution, with a relatively small number of male patients. Furthermore, the sample size was imbalanced between the two groups, which may have caused statistical bias. A prospective study with a large sample size from multiple centers is required to validate our findings.

In conclusion, SPT is a rare pancreatic tumor, with a low grade of malignancy and a strong female preponderance. Compared with female patients, male patients were older, with an average age of 43.1 years, and more male patients were asymptomatic. Radical resection was not necessary in male patients compared with female patients. Surgical strategies should be chosen based on tumor location, size, and adjacent organ compromise, not gender. Complete resection of the tumor can result in good survival, even in patients with vessel involvement or metastases.

Solid pseudopapillary tumor (SPT) of the pancreas is a rare tumor, with low-grade malignancy and a strong female preponderance.

Male patients have been shown to have distinct patterns of onset and aggressiveness compared with female patients. However, this finding is controversial.

This study included the largest number of male patients with SPT from a single institution. Authors investigated the clinical characteristics, surgical strategies and prognosis of SPT in male patients.

Authors established a better understanding of SPT and validated the appropriate surgical strategies for SPT in male patients.

SPT: Solid pseudopapillary tumor.

This manuscript details a very large single center experience in the management of SPT of the pancreas over a 10 year time period. The authors compared the presentation and outcomes for males vs females as well as benign vs malignant SPT. The data is very clearly and concisely presented and the manuscript is written very well. The data contained in the center’s experience is the largest in the world and definitely adds value to the literature regarding what is currently known about this rare pancreatic neoplasm.

P- Reviewers: Coskun A, Du JF, Kai K, Nakazawa T, Ooi LL, Stauffer JA, Sumi S S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Frantz V. Tumors of the Pancreas. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Section vii, Fascicles 27 and 28. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute Pathology 1959; 32-33. |

| 2. | Mao C, Guvendi M, Domenico DR, Kim K, Thomford NR, Howard JM. Papillary cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas: a pancreatic embryonic tumor? Studies of three cases and cumulative review of the world’s literature. Surgery. 1995;118:821-828. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Machado MC, Machado MA, Bacchella T, Jukemura J, Almeida JL, Cunha JE. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: distinct patterns of onset, diagnosis, and prognosis for male versus female patients. Surgery. 2008;143:29-34. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sperti C, Berselli M, Pasquali C, Pastorelli D, Pedrazzoli S. Aggressive behaviour of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in adults: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:960-965. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Potrc S, Kavalar R, Horvat M, Gadzijev EM. Urgent Whipple resection for solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:386-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 7. | Yu MH, Lee JY, Kim MA, Kim SH, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. MR imaging features of small solid pseudopapillary tumors: retrospective differentiation from other small solid pancreatic tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:1324-1332. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nakatani K, Watanabe Y, Okumura A, Nakanishi T, Nagayama M, Amoh Y, Ishimori T, Dodo Y. MR imaging features of solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2007;6:121-126. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Wang XG, Ni QF, Fei JG, Zhong ZX, Yu PF. Clinicopathologic features and surgical outcome of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: analysis of 17 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yu PF, Hu ZH, Wang XB, Guo JM, Cheng XD, Zhang YL, Xu Q. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a review of 553 cases in Chinese literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tien YW, Ser KH, Hu RH, Lee CY, Jeng YM, Lee PH. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: is there a pathologic basis for the observed gender differences in incidence? Surgery. 2005;137:591-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Matos JM, Grützmann R, Agaram NP, Saeger HD, Kumar HR, Lillemoe KD, Schmidt CM. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas: a multi-institutional study of 21 patients. J Surg Res. 2009;157:e137-e142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rebhandl W, Felberbauer FX, Puig S, Paya K, Hochschorner S, Barlan M, Horcher E. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas (Frantz tumor) in children: report of four cases and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2001;76:289-296. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Baek JH, Lee JM, Kim SH, Kim SJ, Kim SH, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. Small (<or=3 cm) solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas at multiphasic multidetector CT. Radiology. 2010;257:97-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cantisani V, Mortele KJ, Levy A, Glickman JN, Ricci P, Passariello R, Ros PR, Silverman SG. MR imaging features of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in adult and pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:395-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Song JS, Yoo CW, Kwon Y, Hong EK. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: three case reports with review of literature. Korean J Pathol. 2012;46:399-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jani N, Dewitt J, Eloubeidi M, Varadarajulu S, Appalaneni V, Hoffman B, Brugge W, Lee K, Khalid A, McGrath K. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: a multicenter experience. Endoscopy. 2008;40:200-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lévy P, Auber A, Ruszniewski P. Do not biopsy solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas! Endoscopy. 2008;40:959; author reply 960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim CW, Han DJ, Kim J, Kim YH, Park JB, Kim SC. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: can malignancy be predicted? Surgery. 2011;149:625-634. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kim MJ, Jang SJ, Yu E. Loss of E-cadherin and cytoplasmic-nuclear expression of beta-catenin are the most useful immunoprofiles in the diagnosis of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:251-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ji S, Xu J, Zhang B, Xu Y, Liu C, Long J, Ni Q, Yu X. Management of a malignant case of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas: a case report and literature review. Pancreas. 2012;41:1336-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chung YE, Kim MJ, Choi JY, Lim JS, Hong HS, Kim YC, Cho HJ, Kim KA, Choi SY. Differentiation of benign and malignant solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:689-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang HL, Shih SC, Chang WH, Wang TE, Chen MJ, Chan YJ. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: clinical experience and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1403-1409. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Papavramidis T, Papavramidis S. Solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas: review of 718 patients reported in English literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:965-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 512] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Kang CM, Kim KS, Choi JS, Kim H, Lee WJ, Kim BR. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas suggesting malignant potential. Pancreas. 2006;32:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee SE, Jang JY, Hwang DW, Park KW, Kim SW. Clinical features and outcome of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: differences between adults and children. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1218-1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |