Published online Jun 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6412

Revised: January 6, 2014

Accepted: February 17, 2014

Published online: June 7, 2014

Processing time: 198 Days and 1.8 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) gastritis may progress to high risk gastropathy and cancer. However, the pathological progression has not been characterized in detail. H. pylori induce persistent inflammatory infiltration. Neutrophils are unique in that they directly infiltrate into foveolar epithelium aiming the proliferative zone specifically. Neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis is a critical pathogenic step in H. pylori gastritis inducing intensive epithelial damage. Epithelial cells carrying accumulated genomic damage and mutations show the Malgun (clear) cell change, characterized by large clear nucleus and prominent nucleolus. Malgun cells further undergo atypical changes, showing nuclear folding, coarse chromatin, and multiple nucleoli. The atypical Malgun cell (AMC) change is a novel premalignant condition in high risk gastropathy, which may progress and undergo malignant transformation directly. The pathobiological significance of AMC in gastric carcinogenesis is reviewed. A new diagnosis system of gastritis is proposed based on the critical pathologic steps classifying low and high risk gastritis for separate treatment modality. It is suggested that the regulation of H. pylori-induced neutrophilic foveolitis might be a future therapeutic goal replacing bactericidal antibiotics approach.

Core tip: Two critical pathogenic steps of high risk Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) gastritis and gastric carcionogenesis are reviewed. Neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis is a critical pathogenic step in H. pylori gastritis inducing intensive epithelial damage. It is suggested to provide a new therapeutic goal replacing traditional bactericidal antibiotics approach. Atypical Malgun cell change is a novel premalignant condition in high risk gastropathy, which may progress and undergo malignant transformation directly. A new diagnosis system of gastritis is proposed based on the critical pathologic steps classifying low and high risk gastritis for separate treatment modality.

-

Citation: Lee I. Critical pathogenic steps to high risk

Helicobacter pylori gastritis and gastric carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(21): 6412-6419 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i21/6412.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6412

It has been 3 decades since Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was first identified[1]. H. pylori is now accepted as the major cause for gastritis and gastric cancer. Numerous investigations for the pathogenesis of H. pylori have been done[2,3], heightening expectations for curative remedies of most gastric diseases. However, the clinical translation of the progress has been so sluggish that current management for gastric diseases is not so much different from the pre-H. pylori era fundamentally. The major therapeutic goal remains to be early detection and curative resection of gastric cancer, and cancer prevention and clinical management at the premalignant stage have a long way to be established.

Antibiotics treatment for H. pylori has been such a controversial issue that it is still not well established as to who should be treated. The high ‘recurrence rate’, potential long term complications, and socioeconomic usefulness of the bactericidal treatment have been disputed. Even the benefits of H. pylori have been suggested such as reducing excessive gastric secretion[4]. However, such potential benefits may not be taken into account in countries like South Korea where the H. pylori infection and gastric cancers are so rampant[5]. To detect gastric cancers at the early stage, endoscopic examinations are done massively nation-wide in Korea. More than 31000 gastric biopsies are done annually in Asan Medical Center alone for all stages of gastritis and advanced lesions. More than 10% of the patients eventually undergo mucosal/surgical resections for cancers. The huge pathologic samples provide an exceptional opportunity to investigate the pathogenesis and progression of H. pylori gastritis to high risk gastropathies.

Most cancers develop after a multi-step carcinogenic process for a long period. However, the pathological progression to high risk H. pylori gastritis and cancer is poorly understood. Gastric cancers are so heterogeneous that it is not easy to define major carcinogenic routes. It probably reflects that most gastric cancers develop after accumulated random genomic damage in persistent inflammation without strong genetic predispositions. Common premalignant lesions, such as tubular adenomas in colon, have been elusive to identify in stomach. Colon-type tubular adenomas are not so frequent in H. pylori gastritis, far less than cancers. Taken together, it is strongly suspected that we have missed or overlooked critical pathogenic steps of H. pylori gastritis and premalignant changes developing under persistent inflammatory pressure. They are likely to be rather common and subtle pathological lesions.

Here, major pathological routes of gastric carcinogenesis including critical pathologic steps and clinical implications are reviewed. Neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis is the pathogenic core of H. pylori gastritis the biological significance of which has largely been overlooked. Surface neutrophilic foveolitis appears to be associated with predisposition for erosion. The atypical Malgun cell (AMC) change is a newly recognized premalignant lesion present in advanced high risk H. pylori gastritis. A new pathologic diagnosis system of gastritis is proposed for practical use.

H. pylori gastritis shows various inflammatory infiltrates including neutrophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, macrophages, and mast cells. Neutrophils are of particular pathobiological significance, because they directly infiltrate into foveolar epithelium while other infiltrates are mostly in lamina propria. Neutrophilic foveolitis is present in H. pylori gastritis worldwide[5], and correlates directly with H. pylori infection[5-7].

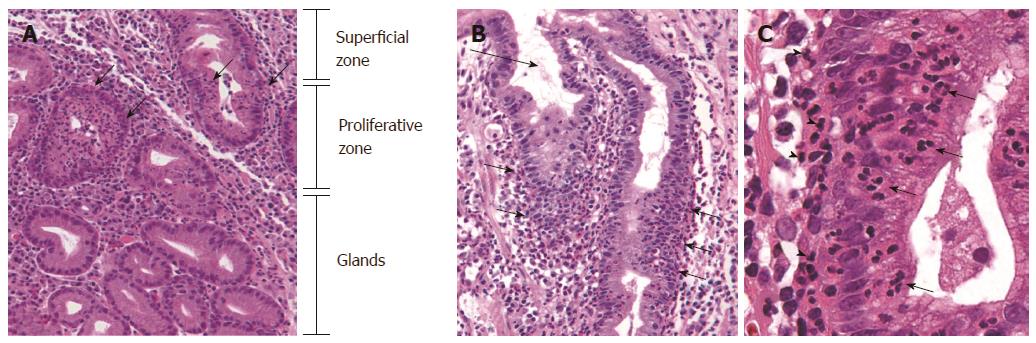

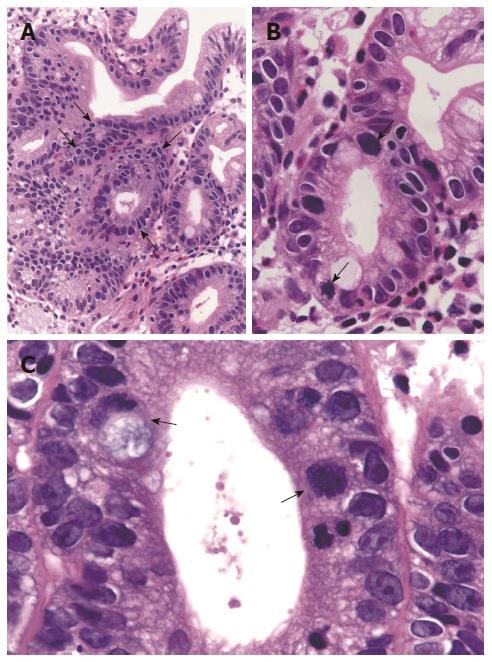

Neutrophilic foveolitis consists of two specific forms, i.e. neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis and surface neutrophilic foveolitis. Neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis (PNF) is the most characteristic feature of H. pylori gastritis, which is shown rarely in other gastritis of alcoholic, chemical, and viral causes. PNF is present in most H. Pylori gastritis regardless of the stage[4-7]. The neutrophilic infiltration is specifically localized to the pit proliferative zone (Figure 1A and B). Lamina propria infiltrates are mostly present close to the foveolar infiltrates (Figure 1C), supporting active movement of neutrophils to the proliferative zone epithelium.

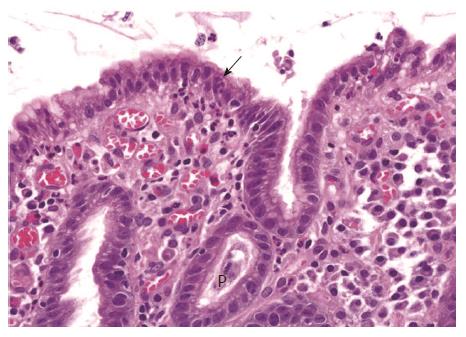

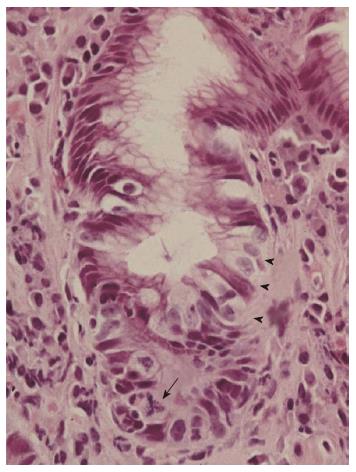

Surface neutrophilic foveolitis (SNF) consists of neutrophilic infiltrates into the surface epithelium (Figure 2). SNF is not as common as the proliferative zone foveolitis, and may be present with or without PNF. SNF is usually associated with a subgroup of patients with intractable recurrent erosion and/or ulcer. In those patients, uninvolved “normal” mucosa often shows surface neutrophilic infiltration, suggesting a genetic predisposition to the epithelial erosion. “Neutrophilic infiltration” has been described in the Sydney system as one of the inflammatory infiltrates in H. pylori gastritis[8]. However, specific details and pathobiological significance have largely been overlooked. Regrettably, it is often described indiscriminately as ‘‘chronic active gastritis’’. Such a description should be discarded, because it does not provide useful clinical information but rather gives a misconception that any gastritis without prominent neutrophils is ‘‘inactive’’. H. pylori gastritis is a progressive disease, and should be taken as ‘‘active’’ at any stage. Neutrophilic foveolitis may not be readily found in small biopsies including intestinal metaplasia or advanced high risk gastritis where H. pylori are rare locally.

It is of interest how neutrophils specifically aim the proliferative zone epithelium. Given that H. pylori penetrate into the borders between epithelial cells[2,3], it is tempting to postulate that neutrophils infiltrate into the proliferative zone where the epithelial junctions are relatively weak compared to surface or deep glandular zones so that H. pylori would easily disrupt the epithelial integrity. The precise mechanism(s) of specific targeting may provide us a future therapeutic target replacing controversial bactericidal antibiotics therapy.

Intense neutrophilic infiltration targeting the proliferative zone has a strong pathobiological impact. Activated neutrophils secrete abundant inflammatory agents damaging the pits, which enhances epithelial proliferation in turn. Such agents as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are mutagenic, inducing accumulated genomic damage in vulnerable epithelial cells in the close vicinity.

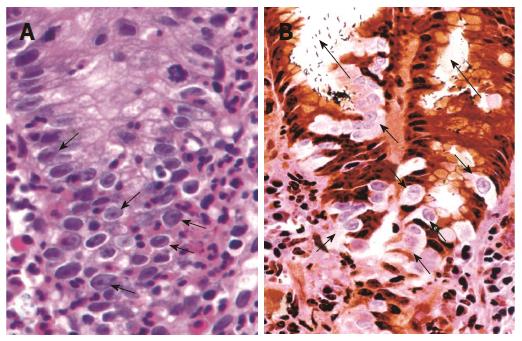

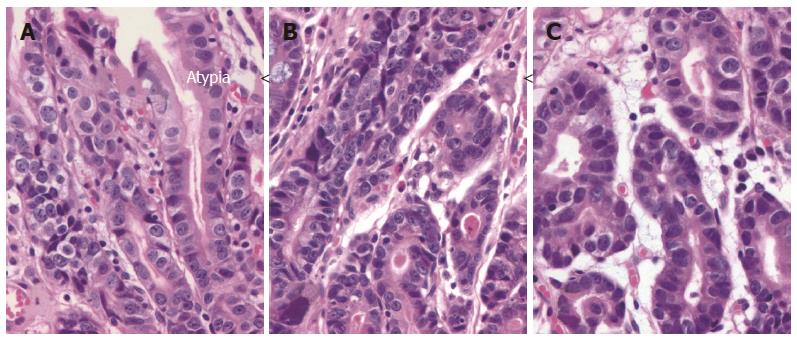

In the proliferative zone with intense neutrophilic infiltrates, epithelial cells begin to show the Malgun(clear) cell change characterized by clear, enlarged nuclei and prominent nucleolus (Figure 3A). The word ‘‘Malgun’’ represents ‘‘clear’’ or ‘‘transparent’’ in Korean[7,9]. The cytoplasm is so tender that a characteristic artifact of ‘‘perinuclear halo’’ is seen frequently due to shrinking in the fixation and embedding process. Malgun cells are demarcated clearly by negative silver staining in contrast to other cells and H. pylori (Figure 3B). Malgun cells have considerable genomic damage, supporting that activated neutrophils indeed induces significant mutagenesis in proliferating epithelial cells[9]. Despite the genomic damage, they manage to keep the proliferative activity and may expand in groups (Figure 3B). Typical Malgun cells may be regarded to reflect the genomic damage inside. The pale face of Malgun cells reminds me of “the Scream” by Edvard Munch, trying to warn the upcoming tragedy loudly to someone. We may have overlooked them, because there are so many all over.

Intestinal metaplasia is very frequent in progressive H. pylori gastritis. By definition, the word ‘‘metaplasia’’ represents a switch from a differentiated cell type to another. What we actually refer to, however, represents a low grade dysplastic condition ‘‘similar to other cell types’’. Strictly speaking, it is a misnomer, but I follow it just to avoid additional unwanted confusion. Nonetheless, it should be reminded that the intestinal metaplasia does not represent ‘‘normal’’ intestinal mucosa but a progressive dysplastic condition at relatively early stage.

Gastritis is a highly variegated process. H. pylori organisms are difficult to find in the metaplastic area. They move to adjacent non-metaplastic mucosa to induce neutrophilic foveolitis in the new colony. Intestinal metaplasia may be regarded as the second best measure for gastric mucosa to avoid fierce neutrophilic foveolitis and to earn some time to take a breath from the relentless attack. However, it represents just another way of mucosal instability with slow progression to high-risk gastritis. In ‘‘advanced’’ or ‘‘complete’’ metaplasia, the mucosa is entirely replaced by metaplastic pits showing paneth cells. It would then undergo further atypical changes progressively.

Upon persistent neutrophilic foveolitis, mucosal damage and repeated erosions give rise to atrophic gastritis eventually. Mucosal atrophy itself would represent not only a poor physiological function but also a limited capacity for ‘‘intrinsic protection’’ against progressive epithelial atypia.

It has been proposed to take the degree and extent of mucosal atrophy for ‘‘staging’’ of gastritis[10]. Mucosal atrophy may indeed be associated with the progression to high risk gastropathy. However, the reproducibility of measurement for atrophy is very doubtful, because it is difficult to examine endoscopic gastric biopsies in standard orientations. Furthermore, the degree of atrophy varies considerably throughout the mucosa. For a practical approach, mucosal atypia rather than atrophy should be the focus of reproducible pathologic examination.

Lymphoid follicles are not present in gastric mucosa normally but often appear in atrophic gastritis, suggesting that atrophy somehow induces lymphoid follicle formation. Individual predisposition may play a role, because not all atrophic gastritis shows lymphoid follicles. Numerous plasma cells in lamina propria would represent a follicular gastritis even if no follicle is present in the given biopsy.

The control of ad hoc follicles in aberrant location seems to be precarious. In advanced follicular gastritis, the mantle and marginal zones often shows irregular expansion which may precede MALT lymphoma. However, such a progression is rare and usually very slow. The fact that “MALT lymphomas” may often be treated with antibiotics strongly suggests a practical over-diagnosis of gastric lymphomas. Nonetheless, excessive expansion of lymphoid follicles and/or evident epithelial infiltration should be included in the pathology report.

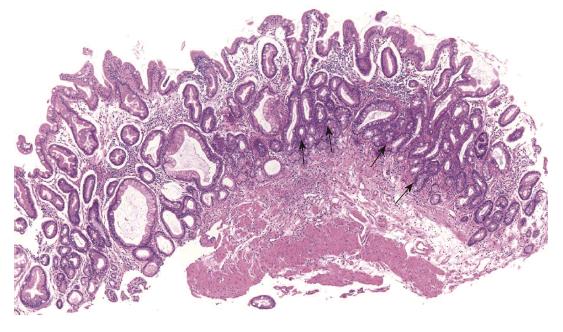

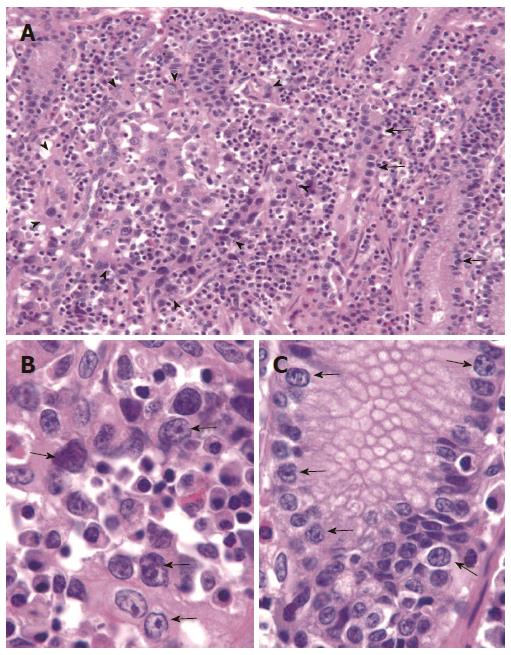

As H. pylori gastritis progresses, the mucosa shows irregular configuration and arrangement with frequent crowding of pits (Figure 4), where Malgun cells gradually show evident atypical change. The AMC change first develops at the proliferative zone and spreads out (Figure 5A). In metaplastic pits, AMC tends to appear at the mucosal bottom (Figure 4), which represents the proliferative zone for the intestinal crypts. AMC have large nuclei and ‘‘perinuclear halo’’ as in classical Malgun cells. However, nuclei are not clear and round anymore; they show irregular folding, hyperchromatism, coarse chromatin, and multiple nucleoli (Figure 5B and C). AMC often show extreme nuclear folding like a mulberry (Figure 5B and C), which may be confused with mitotic figures. Mitoses are also frequent with occasional atypical figures (Figure 6). ‘‘Mulberry cells’’ may be regarded as one of the diagnostic hallmarks for AMC. Histopathological and cytological characteristics of atypical vs classical Malgun cell changes are summarized in Table 1.

| “Typical” malgun cell | Atypical malgun cell | |

| Location | Proliferative/surface zone | Proliferative zone |

| Pits | Elongated proliferative zone | Irregular with crowding |

| Cell size | Enlarged | Enlarged |

| Perinuclear halo | + | + |

| Nuclei | Clear | Hyperchromatic |

| Chromatin | Euchromatin | Heterochromatin |

| Nucleoli | 1 (or 2) | 2 (or multiple) |

| Nuclear envelope | Smooth | Folded |

| Mulberry cells | - | + |

| In metaplasia | - | +/- |

| Malignant transformation | - | + |

AMC represents a progressive high risk gastropathy. The cellular and structural atypia increases as it progresses, and atypia of variable degrees may be present simultaneously in a patient (Figure 7). AMC may progress to overt ‘‘epithelial dysplasia’’ consisting of crowded glands of high grade atypia. Colon type tubular adenomas may develop in metaplastic gastritis, but are relatively infrequent.

Like AMC, gastric carcinomas first develop at the proliferative zone and spreads out laterally in the mucosa. Cancers frequently develop in AMC without any other evident premalignant lesion (Figure 8A). Cytologic figures of early cancers are often very similar to adjacent AMC (Figure 8B and C), supporting that cancers, particularly diffuse type carcinomas, develop directly from AMC. As cancers grow, the histological features may change depending on which cell clones emerge to dominate. Other evidences also support the pathobiological role of AMC in carcinogenesis. On long-term follow up, gastric cancers seem to develop much more frequently in AMC compared to gastritis without AMC, supporting the notion that AMC is a premalignant lesion. A prospective epidemiological study is under progress.

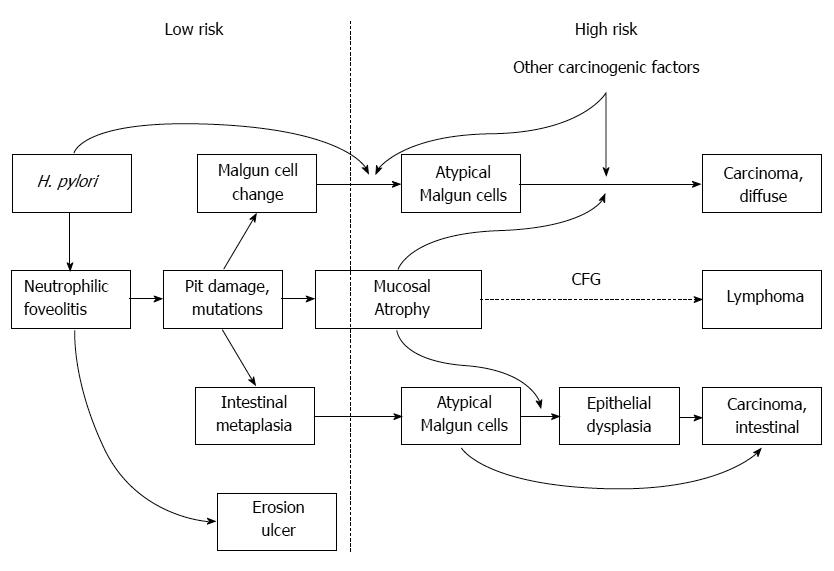

Major carcinogenic routes from chronic H. pylori gastritis are summarized in Figure 9. H. pylori infection induces neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis that is by far the most critical initial pathogenic step causing intense and persistent pit damage and mucosal erosion. Epithelial cells then show the Malgun cell change and/or intestinal metaplasia. As genomic damage is accumulated, typical Malgun cells and metaplastic cells progress to AMC, a critical pathological feature representing high risk gastritis. Cancers, particularly diffuse type carcinomas, may develop directly from AMC. Intestinal type cancers mostly develop from AMC in metaplastic gastritis with or without overt epithelial dysplasia. Mucosal atrophy, persistent inflammatory pressure, and other carcinogenic factors would promote the malignant transformation together. Lymphomas may develop in association with chronic follicular gastritis arising in atrophic mucosa. The proposal is to depict major carcinogenic routes for the majority of gastric cancers but not to cover all pathways.

A practical system for pathologic diagnoses for gastritis is proposed in Table 2. Superficial congestive gastritis (SCG) represents an acute process with mucosal edema, capillary congestion, and mild inflammatory infiltration. Regenerative atypia may be found in elderly subjects (SCG-Ad), which may reflect healed epithelial “scarring”.

| Superficial congestive gastritis (SCG) |

| SCG with epithelial regenerative change (SCG-Ad) |

| Erosive gastritis (EG) |

| EG with prominent neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis (EG-PNF) |

| EG with superficial neutrophilic foveolitis (EG-SNF) |

| EG, advanced (EG-Ad) |

| EG with atypical Malgun cell change (EG-AMC) |

| Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) |

| CAG, advanced (CAG-Ad) |

| CAG with AMC (CAG-AMC) |

| Chronic follicular gastritis (CFG) |

| CFG, advanced (CFG-Ad) |

| Chronic metaplastic gastritis (CMG) |

| CMG-Ad |

| CMG-AMC |

| Epithelial dysplasia (DYS) |

| DYS-high grade (DYS-H) |

| General addendum, if necessary |

| H. pylori +/- |

| dominant infiltrate, etc. |

Erosive gastritis (EG) shows inflammatory infiltration with epithelial damage. EG-PNF represents EG with prominent neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis. Antibiotics treatment may be recommended to prevent rapidly progressive mucosal damage. EG with superficial neutrophilic foveolitis represents an evident superficial epithelial neutrophilic gastritis with or without EG-PNF. It consists of a minor population of EG prone to intractable erosive disease for whom anti-acid and/or -secretory regulators would be helpful. Adavanced EG (EG-Ad) represents longstanding EG with elongated proliferative zone, epithelial damage, and frequent typical Malgun cells. Cellular and glandular atypia should not be significant. EG with AMC (EG-AMC) should be regarded as a high risk gastritis so that patients are followed-up regularly. EG-Ad progresses to EG-AMC gradually. The points for the differential diagnosis are summarized in Table 1.

Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) is confirmed when the tissue sample is oriented well so that the entire length of pits may be assessed. CAG should not be confused with ‘‘chronic active gastritis’’, which should be discarded at once for many reasons as described. Advanced CAG (CAG-Ad) represents severe mucosal atrophy with or without significant epithelial atypia. Both CAG-Ad and CAG-AMC are regarded as high-risk groups. Chronic follicular gastritis (CFG) is mostly associated with mucosal atrophy. Advanced CFG represents gastritis with enlarged lymphoid follicles and irregularly expanded mantle zone into of adjacent pits. No lymphoid cellular atypia or overt epithelial infiltration is to be included.

Chronic metaplastic gastritis (CMG) consists of intestinal metaplasia and mild inflammatory infiltration. Local H. pylori and neutrophilic foveolitis are absent or rare in CMG. Advanced CMG represents an extensive metaplasia replacing the whole mucosal layers with frequent paneth cells. The cellular atypia should be minimal. CMG with AMC (CMG-AMC) is quite common form of high risk gastritis. AMC shows considerable cellular atypia, increased mitoses, and occasional Mulberry cells. Gastric cancers may develop directly from CMG-AMC.

Epithelial dysplasia is regarded to be a neoplastic change, showing crowded atypical glands. Colon-like tubular adenomas developing in CMG are included in this category. High grade dysplasia shows severe cellular and structural atypia of pits, and represents an imminent malignant change. Local mucosal resection should be considered whenever applicable.

Multiple diagnoses in the proposal may be made for a given case. In such a case, the diagnosis of grave clinical implication should be placed first. The histological presence of H. pylori may also be described. We do not mention it anymore in our pathology report unless it is in high risk gastritis or an antibiotics therapy is warranted such as EG-PNF.

Gastric cancers represent a typical inflammation-induced malignancy arising after accumulated mutations and genomic damage mostly induced by H. pylori infection. Neutrophilic proliferative zone foveolitis is the core of pathogenesis of H. pylori gastritis and cancers. Detailed descriptions of neutrophilic foveolitis should be included in the pathological diagnosis of gastritis. Surface neutrophilic foveolitis may be treated as a separate subgroup prone to erosion and/or ulcer.

Neutrophilic foveolitis may be implicated in the future development of therapeutics for H. pylori gastritis. The ‘‘eradication’’ of H. pylori using traditional bactericidal antibiotic therapy is controversial. After all, the bacteria have been together with us through the evolution as a member of human microbiota. We may now consider changing the direction of therapeutic approach. Control of neutrophilic foveolitis induced by H. pylori may be a good alternative goal for future therapy. The mechanism(s) of inducing neutrophilic foveolitis should be investigated thoroughly. I suggest to screen widely for safe remedies, synthetic or natural, to control the motility of H. pylori for immediate clinical trials. Active intercellular penetration of H. pylori is likely to be critical for inducing neutrophilic infiltration particularly at the proliferative zone of vulnerable epithelial cells.

AMC represents a premalignant lesion from which gastric cancers may develop directly. It has been largely overlooked, because, ironically, it is so common in advanced H. pylori gastritis. The molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis from AMC need to be investigated in detail. The proposed diagnostic system would be useful for defining high risk group gastritis objectively. Separate clinical management of high risk gastritis would be important for appropriate patient care as well as efficient use of the medical resources socioeconomically. High risk group gastritis/gastropathy consists of about 5%-10% of all gastric biopsies in our population. Considering that biopsies are taken from a minor group of endoscopic examinations, high risk group gastritis of the whole population should be within manageable range for follow-up care even in such a high prevalence society of H. pylori gastritis as Korea.

P- Reviewers: Budzynski J, Mori N, Shi Y S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311-1315. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Salama NR, Hartung ML, Müller A. Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:385-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Atherton JC. The pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastro-duodenal diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:63-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1863-1873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee I, Lee H, Kim M, Fukumoto M, Sawada S, Jakate S, Gould VE. Ethnic difference of Helicobacter pylori gastritis: Korean and Japanese gastritis is characterized by male- and antrum-predominant acute foveolitis in comparison with American gastritis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:94-98. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yu E, Lee HK, Kim HR, Lee MS, Lee I. Acute inflammation of the proliferative zone of gastric mucosa in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:689-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee H, Jang J, Kim Y, Ahn S, Gong M, Choi E, Lee I. “Malgun” (clear) cell change of gastric epithelium in chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196:541-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161-1181. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jang J, Lee S, Jung Y, Song K, Fukumoto M, Gould VE, Lee I. Malgun (clear) cell change in Helicobacter pylori gastritis reflects epithelial genomic damage and repair. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:1203-1211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, Graham DY. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007;56:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |