Published online May 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5283

Revised: November 28, 2013

Accepted: January 19, 2014

Published online: May 14, 2014

Processing time: 230 Days and 20.8 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is highly associated with the occurrence of gastrointestinal diseases, including gastric inflammation, peptic ulcer, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma. Although alternative therapies, including phytomedicines and probiotics, have been used to improve eradication, current treatment still relies on a combination of antimicrobial agents, such as amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin, and antisecretory agents, such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). A standard triple therapy consisting of a PPI and two antibiotics (clarithromycin and amoxicillin/metronidazole) is widely used as the first-line regimen for treatment of infection, but the increased resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin and metronidazole has significantly reduced the eradication rate using this therapy and bismuth-containing therapy or 10-d sequential therapy has therefore been proposed to replace standard triple therapy. Alternatively, levofloxacin-based triple therapy can be used as rescue therapy for H. pylori infection after failure of first-line therapy. The increase in resistance to antibiotics, including levofloxacin, may limit the applicability of such regimens. However, since resistance of H. pylori to amoxicillin is generally low, an optimized high dose dual therapy consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin can be an effective first-line or rescue therapy. In addition, the concomitant use of alternative medicine has the potential to provide additive or synergistic effects against H. pylori infection, though its efficacy needs to be verified in clinical studies.

Core tip: This article provides a review of therapeutic agents and therapies that have been used in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Factors that may affect treatment outcome are described and therapeutic strategy is recommended.

-

Citation: Yang JC, Lu CW, Lin CJ. Treatment of

Helicobacter pylori infection: Current status and future concepts. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(18): 5283-5293 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i18/5283.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5283

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), initially named Campylobacter pyloridis, was first identified in humans and cultured by Marshall and Warren[1]. It is a microaerophilic, spiral-shaped, Gram negative bacterium, with several polar flagella for mobility. It can only survive at a periplasmic pH of 4.0-8.5 and can only grow at a periplasmic pH of 6.0-8.5. One well-known biochemical characteristic of H. pylori is its ability to produce urease, which can hydrolyze gastric urea to liberate ammonia, neutralizing the gastric acid and increasing the periplasmic pH to 4.0-6.0, thus protecting H. pylori from gastric acid[2,3].

The exact routes of H. pylori transmission remain unclear. However, epidemiologic studies have shown that exposure of food to contaminated water or soil may increase the risk of H. pylori infection, suggesting that person-to-person transmission by oral-oral, fecal-oral, or gastro-oral exposure is the most likely path for H. pylori infection[4]. Accordingly, improvements in hygiene and living conditions are important factors in decreasing the prevalence of infection[5]. More than 50% of the world’s population has been infected by H. pylori and the prevalence of infection in developing countries is greater than 80% in adults over 50 years of age. Infected individuals usually acquire H. pylori before 10 years of age and grow up with the infection[6]. In Asia, the prevalence of H. pylori infection varies in different countries, the reported overall seroprevalence rates being about 31% in Singapore, 36% in Malaysia, 39% in Japan, 55% in Taiwan, 57% in Thailand, 58.% in China, 60% in South Korea, 75% in Vietnam, 79% in India, and 92% in Bangladesh[7].

H. pylori infection is highly associated with gastrointestinal diseases, including gastric inflammation, peptic ulcer, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma[8-11]. It has been classified as a group 1 carcinogen (i.e., infection with H. pylori is carcinogenic in humans) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer consensus group since 1994[12] and many guidelines have been established for treatment of H. pylori infection[13-16].

Treatment of infection relies on a combination of antimicrobial agents and antisecretory agents, the elevation of the gastric pH by antisecretory agents being required for the bactericidal effect of the antimicrobial agents. Alternatively, although the mechanism of action is not yet clear, phytomedicines and probiotics have been used to improve eradication of H. pylori.

The effect of antimicrobial agents and antisecretory agents depends not only on their pharmacological activities, but also on their pharmacokinetic properties. Many antimicrobial agents, including amoxicillin, clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, tetracycline, rifabutin, and bismuth-containing compounds, have been used for H. pylori therapy, while the main antisecretory agents used are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

The effect of most antimicrobial agents used for H. pylori treatment, including clarithromycin, levofloxacin, and metronidazole, is concentration-dependent, i.e., their efficacy is proportional to their plasma concentration[17-19]. In the case of clarithromycin, the breakpoint proposed for susceptible strains is 0.25 μg/mL and that for resistant strains > 0.5 μg/mL[20], while, for levofloxacin and metronidazole, the breakpoints proposed for resistant strains are > 1 μg/mL and > 8 μg/mL, respectively, as determined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing[21]. In contrast to the effects of the concentration-dependent antibiotics, the bactericidal effect of amoxicillin against H. pylori is time-dependent, i.e., its efficacy is proportional to the time that the plasma concentration is higher than the MIC[22-24], and the breakpoint proposed for resistant strains is usually > 0.5 μg/mL, although a more stringent breakpoint (> 0.12 μg/mL) was determined by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing for H. pylori resistance to amoxicillin[21]. Many bismuth salts are poorly soluble in water and are therefore very weakly absorbed and thus exert their activity by local action in the gastrointestinal tract. The MIC for bismuth to prevent the growth of 90% of H. pylori has been reported as 4 to 32 ng/L[25]. A post-antibiotic effect against H. pylori has been demonstrated for clarithromycin and levofloxacin[26,27].

In terms of resistance, a change in the properties of penicillin-binding protein, either a decreased affinity for amoxicillin[28] or point mutation in the pbp1A gene[29], is the main mechanism leading to amoxicillin resistance of H. pylori. Other mechanisms for amoxicillin resistance may include a reduced membrane permeability, leading to low accumulation of amoxicillin[30]. For clarithromycin, the major mechanism for resistance is point mutation in the 23S rRNA gene, the most frequent being at A2143G (69.8%), followed by A2142G (11.7%) and A2142C (2.6%)[31]. Point mutation of gyrA, coding for DNA gyrase, in the codons coding for amino acid 87, 88, 91, or 97 has been observed in levofloxacin-resistant isolates[32,33]. For metronidazole, null mutations in the rdxA gene, which codes for oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitroreductase (RdxA), have been identified in metronidazole-resistant strains of H. pylori. Other genes, such as frxA (coding for NADPH flavin oxidoreductase), and fdxB (coding for ferredoxin-like enzyme), also play a role in the mechanisms of resistance to metronidazole[34-36]. For rifabutin, H. pylori mutants with mutations in codons 524-545 or codon 585 of the rpoB gene are resistant to rifabutin[37,38]. Additionally, cross resistance between rifabutin and rifampin has been reported[39]. The prevalence of rifabutin resistance is 1.3% overall, but can be as high as 31% in post-treatment patients[40]. H. pylori resistance to bismuth salts is rare[41], and colloidal bismuth subcitrate has been reported to prevent the development of H. pylori resistance to nitronidazole[42].

Although H2-receptor antagonists can be used as antisecretory agents, PPIs are more effective in increasing the gastric pH. PPIs inhibit the gastric acid pump (H+/K+ATPase), which is responsible for the secretion of hydrochloric acid and is located in the canalicular membrane of gastric parietal cells[43]. At low pH, PPIs are protonated, then undergo cyclization to form a tetracyclic sulfonamide, which binds irreversibly to cysteines in the α subunit of the H+/K+ATPase and inhibits the H+/K+ATPase[44]. Thus, the accumulation and action onset of PPIs rely on their acid ionization constant (pKa), with a higher pKa allowing greater conversion to the active sulfonamide. Of the PPIs, rabeprazole has the highest pKa (pKa = 4.9), followed by omeprazole (pKa = 4.13), lansoprazole (pKa = 4.01), and pantoprazole (pKa = 3.96)[45].

Most PPIs are primarily metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. Thus, their pharmacological effects are influenced by endogenous (e.g., pharmacogenetic polymorphism) and exogenous (e.g., drug-drug interaction) factors. The CYP2C19 genotype is known to influence the pharmacokinetic properties of PPIs. The ratios of the half-life (t1/2) value in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers to that in extensive metabolizers (EMs) is 2.2, 2.1, 1.9, and 1.4 for omeprazole, (-) pantoprazole, lansoprazole, or rabeprazole, respectively, and the corresponding ratios of the area under the curve (AUC) values are 7.4-6.3, 10.7-2.5, 4.3-1.9, and 1.8-1.2[46-51]. While most PPIs are used as racemic mixtures of two optical isomers, esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, is available on the market, and an in vitro study showed that, compared to omeprazole, it is metabolized to a greater extent by CYP3A4 and to a lesser extent by CYP2C19 and that esomeprazole itself is mainly metabolized by CYP3A4[52]. However, in patients receiving esomeprazole, the CYP2C19 genotype still plays an important role in the acid-inhibitory effect and H. pylori eradication[53,54], and this also applies to patients taking dexlansoprazole, the R-isomer of lansoprazole[55].

PPIs also have a direct antimicrobial activity against H. pylori. Nakao and Malfertheiner[56] compared the growth inhibitory activity of omeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole against 58 clinical isolates of H. pylori. and found that the MIC90 for lansoprazole was 6.25 μg/mL, lower than that of omeprazole (25 μg/mL) or pantoprazole (100 μg/mL). Kawakami et al[57] compared the anti-H. pylori activity of rabeprazole, rabeprazole thioether, lansoprazole, omeprazole, and three antibiotics (amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole) and found MIC90 values of 0.5 μg/mL for rabeprazole, 0.25 μg/mL for rabeprazole thioether, 1 μg/mL for lansoprazole, 16 μg/mL for omeprazole, 0.031 μg/mL for amoxicillin, 1 μg/mL for clarithromycin, and 16 μg/mL for metronidazole.

While antibiotics are the main agents used in the therapy of H. pylori infection, the development of resistance has limited their application. Also, administration of antibiotics perturbs the microbiota, the microorganisms that colonize the human gastrointestinal tract, and thus causes side effects, such as diarrhea. Because of this, alternative therapies, including the use of phytomedicines and probiotics, have been used for the treatment of H. pylori infection.

There is increasing evidence that traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) are efficacious in the treatment of various diseases. The efficacy and safety of TCMs for the treatment of H. pylori have been reviewed and the average eradication rate was found to be about 72%[58], suggesting that TCMs may not be a stand-alone therapy for H. pylori infection Nevertheless, the role of TCMs in H. pylori treatment remains to be clarified. In addition to TCMs, other phytomedicines that have been used for the treatment of H. pylori infection are green tea catechins, garlic extract, cranberry juice, and propolis[59]. For example, it has been demonstrated that a combination of catechins and sialic acid can effectively prevent H. pylori infection in animals and improve the eradication rate[60,61]. As catechins and sialic acid have different anti-bacteria actions, the additive or synergistic effects caused by such a combination may provide a potential strategy for treating H. pylori infection in the future. However, since most studies have been carried out in vitro or in animals, the efficacy of phytotherapy in humans needs to be verified by suitable clinical trials.

Probiotics are living organisms that are administered orally to confer a health benefit on the host. In recent years, the application of probiotics in the treatment of H. pylori infection has become an active research field. Several probiotics, including Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) and Lactobacillus strains, have been combined with antibiotic-containing therapies to treat infection. Compared to standard triple therapy, although addition of S. boulardii significantly reduced the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, it did not significantly improve the eradication rate of H. pylori[62-64]. Likewise, addition of Lactobacillus GG significantly reduced the incidence of diarrhea, but did not improve the eradication rate of triple therapy[62,65]. Addition of Lactobacillus acidophilus was reported to significantly increase treatment outcome of triple therapy[66], but, in another study, addition of the combination of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis failed to show an improvement in H. pylori eradication[62]. Intriguingly, in contrast to the capsule/sachet-based probiotic preparations, fermented milk-based probiotics have been reported to improve H. pylori eradication rates by about 5%-15%[67], possibly because some of contain additional components (e.g., lactoferrin and glycomacropeptide) that may inhibit H. pylori.

Various combinations of PPIs and antimicrobial agents have been designed to treat H. pylori infection. These regimens include triple therapy, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, sequential therapy, and concomitant therapy (non-bismuth quadruple therapy). The Maastricht I Consensus Report recommended that treatment regimens should achieve an eradication rate of at least 80% and proposed a standardized report card to be used to evaluate the outcome of new therapeutic regimens for H. pylori infection[68], on which the efficacy of an anti-H. pylori regimen is graded as A or excellent if the eradication rate is 95%-100% in the intention-to-treat analysis, while an eradication rate of 90%-95% is considered as B or good, 85%-89% as C or fair, 81%-84% as D or poor, and ≤ 80% as F or unacceptable.

Guidelines for the management of H. pylori infection are still evolving and, depending on the geographic areas, first-line, alternative first-line, second-line, or even third-line therapies have been proposed. Recent guidelines proposed for Asia-Pacific regions, developing countries, Europe, and United States are summarized in Table 1. Despite these guidelines being proposed for different areas, the regimens suggested for first-line and rescue treatments are generally similar.

| Treatment | Asia-Pacific region[13] | Developing countries[14] | Europe[15] | United States[16] |

| First-line | Triple therapy | Triple therapy | Triple therapy | Triple therapy |

| (PPI + CLA + AMO/MET) | (PPI + CLA + AMO/FUR) | (PPI-CLA-containing regimen) | (PPI + CLA + AMO/MET) | |

| BIS-based quadruple therapy | Quadruple therapy | BIS-based quadruple therapy | BIS-based quadruple therapy | |

| (PPI + BIS + MET + TET) | (PPI + CLA + AMO + BIS/MET or PPI + BIS + MET + TET) | (for high clarithromycin resistance) | (BIS + MET + TET + RAN) | |

| Sequential therapy | Sequential therapy | |||

| Sequential therapy | (for high clarithromycin resistance) | (PPI + AMO and PPI + CLA + TIM) | ||

| (PPI + AMO and PPI + CLA + NIT) | ||||

| Second-line | BIS-based quadruple therapy | BIS-based quadruple therapy | BIS-based quadruple therapy | BIS-based quadruple therapy |

| (PPI + BIS + MET + TET) | (PPI + BIS + TET + MET/FUR) | LEV-based triple therapy | (PPI + TET + BIS + MET) | |

| LEV-based triple therapy | LEV-based triple therapy: | LEV-based triple therapy | ||

| (PPI + LEV + AMO) | (PPI + LEV + BIS/FUR/AMO) | (PPI + AMO + LEV) | ||

| RIF-based triple therapy | ||||

| (PPI + RIF + AMO) | ||||

| Third-line | RIF-based triple therapy | LEV-based or FUR-based triple therapy | Guided by antimicrobial susceptibility testing | |

| (PPI + RIF + AMO) | (PPI + AMO + LEV/RIF or | |||

| PPI + FUR + LEV) |

According to current guidelines, standard triple therapy containing a PPI and two antibiotics, clarithromycin and amoxicillin/metronidazole, is the first-line regimen for treatment of H. pylori infection[13-16]. The recommended therapeutic duration of standard triple therapy is 7 d in Europe and Asia, but 10-14 d in the United States. Although triple therapy is considered to be a standard first-line therapy, the most recent data show that the efficacy of standard triple therapy is decreasing and that the eradication rate of standard triple therapy in some areas is less than 80%[32,69]. To improve the eradication rate of triple therapy, Furuta et al[70] proposed a tailored regimen based on CYP2C19 genotype and bacterial susceptibility to clarithromycin, and showed a 96% intention-to-treat eradication rate. Although this pharmacogenomics-based strategy is promising, it requires genotype testing in advance and the cost-effectiveness remains to be verified. Alternatively, the new version of the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report[15] has updated the recommendations for first-line therapy, and bismuth-containing quadruple therapy has been officially substituted for standard triple therapy in areas in which the clarithromycin resistance rate is over 15%-20%. However, due to side effects, bismuth is no longer available in many countries, including Japan, Malaysia, and Australia, and, as a result, bismuth-containing therapy is not used in these areas, so sequential treatment or a non-bismuth quadruple therapy (concomitant treatment) is recommended as the alternative first-line treatment in high clarithromycin resistance area.

Ten-day sequential therapy, with an eradication rate of 98%, was proposed in 2000[71]. It consists of 5-d dual therapy (PPI plus amoxicillin), followed by 5-d triple therapy [PPI plus clarithromycin and a nitronidazole (metronidazole or tinidazole)]. Compared to 7-d standard triple therapy, sequential therapy was found to result in higher eradication rates (intention-to-treat 92% vs 75%; per-protocol 95% vs 77%)[72]. A meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials with 3011 patients calculated eradication rates of 91.0% (95%CI: 89.6-92.1) for sequential therapy and 75.7% (95%CI: 73.6-77.7) for standard triple therapy[73]. Using the suggested report card classification, sequential therapy was scored as B or good, while standard triple therapy was only scored as an F or unacceptable[68]. Sequential therapy is therefore recommended as an alternative to standard triple therapy for H. pylori infection[14-16]. Nonetheless, a study conducted at 7 Latin American sites demonstrated that 14-d triple therapy was superior to 10-d sequential therapy in eradication of H. pylori infection[74], suggesting that the application of sequential therapy as first-line therapy still requires validation in certain areas.

Although containing two dosing periods, sequential therapy is basically a quadruple therapy consisting of one PPI and three antibiotics. In 1998, before sequential therapy was proposed, two groups of investigators reported the use of a non-bismuth based quadruple therapy (i.e., concomitant quadruple therapy) containing omeprazole, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and clarithromycin/ roxithromycin for 5 d or 1 wk and showed an eradication rate higher than 90%[75,76]. The result of meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials conducted during 1998 and 2007 showed that concomitant quadruple therapy was superior to standard triple therapy in terms of intention-to-treat and per-protocol[77]. Compared to sequential therapy, concomitant quadruple therapy has been demonstrated to be safe and equally effective in eradication of H. pylori infection[78], and the same study demonstrated that dual resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole did not influence the eradication rate of concomitant quadruple therapy, but did significantly affect that of sequential therapy.

After failure of first-line therapy for H. pylori infection, in addition to bismuth-containing quadruple therapy, levofloxacin-based triple therapy is recommended as rescue therapy. The efficacy of one-week levofloxacin-based triple therapy containing a PPI plus levofloxacin and amoxicillin/nitroimidazole (metronidazole or tinidazole) was first evaluated as a first-line treatment in 2000, and a high eradication rate of 90%-92% was observed[79]. However, when it was compared to 7-d clarithromycin-based triple therapy as either a first-line or rescue therapy in a cross-over design study[80], when used as first-line treatment, clarithromycin-based triple therapy gave a significantly higher eradication rate than levofloxacin-based triple therapy (83.7% vs 74.2%, P = 0.015); however, when used as rescue treatment, levofloxacin-based triple therapy achieved a higher eradication rate than clarithromycin-based triple therapy (76.9% vs 60%, P = 0.154). In addition, the overall eradication rate of clarithromycin-based triple therapy followed by levofloxacin-based triple therapy was significantly higher than that achieved using the reverse sequence (93.0% vs 85.3%, P = 0.01). These findings suggest that levofloxacin-based triple therapy should be used as second-line treatment, rather than first-line treatment.

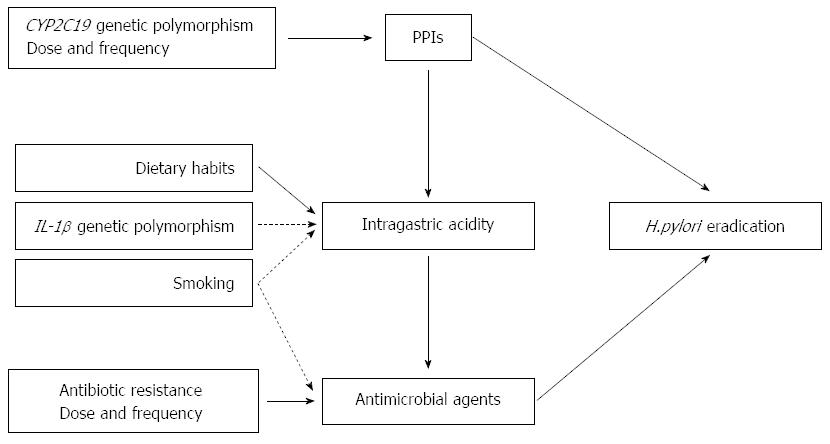

In addition to patient adherence, a number of other factors can influence treatment outcome; these include antibiotic resistance, genotypes [CYP2C19 and IL: Interleukin (IL)1-β polymorphisms], and intragastric acidity. Since PPIs and antibiotics are the major agents used to eradicate H. pylori, factors that affect the pharmacokinetics (e.g., CYP2C19 polymorphism for PPIs) or pharmacodynamics (e.g., drug resistance or time/concentration-dependency of antibiotics) of these drugs can determine the evolution of the management of H. pylori infection (Figure 1). The impact of CYP2C19 genotype on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of PPIs in H. pylori treatment has been reviewed previously[81].

The major effect of PPIs in the treatment of H. pylori infection is to increase the intragastric pH, as the intragastric pH is important not only for the efficacious effect of antibiotics, but also for the growth of H. pylori. In two studies[81,82], the mean percentage of time that the intragastric pH was higher than 4 was found to be longer in patients cured of H. pylori infection than in those who were not cured (84% ± 11% vs 58% ± 9%, P < 0.001), and patients who were cured had a mean 24-h intragastric pH higher than 5.5. Factors that can influence the intragastric pH include CYP2C19 genotype, IL-1β genotype, and dose frequency of PPIs. When 40 mg rabeprazole was given once daily, the median intragastric pH was 4.3, 4.7, and 5.9 in patients who were CYP2C19 EMs, intermediate metabolizers (IMs), and PMs, respectively[83]. On the other hand, a regimen of rabeprazole 10 mg four times daily maintained the intragastric pH at a value higher than 6.5 regardless of CYP2C19 genotype[83,84], showing that a dose frequency of four times daily is beneficial in providing sufficient inhibition of acid production in patients whose CYP2C19 genotype is not known. However, CYP2C19 polymorphism is not the only factor to consider, as it has been shown that H. pylori-infected patients with the IL-1β-511 T/T genotype have higher mucosal levels of IL-1β[85], a potent inhibitor of gastric acid secretion, which leads to an increase in the gastric pH, which plays a role in the therapy of H. pylori infection. The IL-1β-511 T/T genotype has been found to be related to a better outcome of standard triple therapy using omeprazole, lansoprazole, or rabeprazole[86,87].

In terms of the effects of antibiotics, as described in previous sections, the dose and frequency of dosing of antimicrobial agents should be determined by whether their efficacy is time- or concentration-dependent. For time-dependent antibiotics (e.g., amoxicillin), it is more important to prolong the time that the plasma concentration is higher than the MIC, rather than achieve higher drug levels. On the other hand, for concentration-dependent antibiotics (e.g., clarithromycin, levofloxacin, and metronidazole), it is more important to achieve higher plasma levels, within a reasonable range. A regimen chosen by considering these characteristics can improve treatment outcome. In addition to the dosing regimen, the increase in H. pylori resistance to antibiotics has also become an important factor in the efficacy of therapeutic regimens. The resistant rates of H. pylori to amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin are different among geographic areas (Table 2). Among these, the most important one is probably the resistance to clarithromycin, which is the key component of many regimens. The prevalence of clarithromycin resistance is more than 20% in China, Japan, and most countries in Europe[69,88-90]. Between 1998 and 2008, the clarithromycin resistance rates in Europe and Japan increased, respectively, from 9% to 17.5% and from 6.4% to 27.1%[88,91,92]. A meta-analysis showed that clarithromycin resistance caused a 66% reduction in the eradication rate of standard triple therapy containing a PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin[93].

| Africa | Asia | Europe | United States | |

| Amoxicillin | 17.8% | 1.9% | 0.5% | 2.2% |

| Clarithromycin | 13.4% | 21.0% | 11.1% | 29.3% |

| Metronidazole | 86.2% | 38.1% | 17.0% | 44.1% |

| Levofloxacin | NA | 14.0% | 24.1% | NA |

In addition to clarithromycin resistance, resistance to metronidazole is also important. The metronidazole resistance rate varies greatly in different geographical areas, being 92.4% in Africa, 44.1% in America, 37.1% in Asia, and 17.0% in Europe[89]. The prevalence of metronidazole resistance in developing countries is much higher than in developed countries, possibly due to the common use of metronidazole to treat parasitic infections in developing countries[94]. Metronidazole resistance also affects the efficacy of standard triple therapy containing a PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole. In metronidazole-susceptible strains, the eradication rate of triple therapy was found to be 97%, much higher than the value of 72.6% for metronidazole-resistant strains[3,93]. In contrast to clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance, the prevalence of amoxicillin resistance is usually less than 1%[69], and the impact of amoxicillin resistance on treatment outcome is still unclear. On the other hand, although the use of quinoline antibiotics, such as levofloxacin, has resulted in sufficiently satisfactory therapeutic outcomes to allow its use instead of clarithromycin in standard triple therapy regimen, the rapid acquisition of levofloxacin resistance may reduce its effectiveness and should be taken into account[15].

The high resistance rate of H. pylori to clarithromycin and metronidazole can significantly affect the efficacy of any regimens containing these medications. In contrast, worldwide primary amoxicillin resistance of H. pylori is generally low and secondary resistance to amoxicillin is also rare, even though it is a common medication in standard triple therapy[95-97], and it is therefore advantageous to use amoxicillin in the treatment of H. pylori infection. Dual therapy using the combination of a PPI (omeprazole) and amoxicillin was first investigated in 1989 and resulted in a better eradication rate (62.5%) than treatment with either PPI alone (0%) or amoxicillin alone (14.2%)[98]. High dose dual therapy consisting of 40 mg omeprazole and 750 mg amoxicillin given three times daily was first proposed in 1995 and gave an eradication rate for H. pylori infection greater than 90%[99]. In contrast to regular dual therapy, in high dose dual therapy, the PPI is given three or four times daily, rather than once or twice daily (Table 3). High dose dual therapy also seems to ameliorate the impact of CYP2C19 genotype. Furuta et al[100] evaluated the eradication rate for H. pylori in patients with different CYP2C19 genotypes receiving rabeprazole (10 mg) and amoxicillin (500 mg) four times daily and found eradication rates of 100% in both the EM and IM groups.

| Author | Role | Regiment | Patients, n | Eradication rate | ||||

| ITT | PP | CYP2C19 | ||||||

| EM | IM | PM | ||||||

| Bayerdörffer et al[99] | 1st | OME 40 mg and AMO 750 mg tid for 14 d | 139 | 89.0% | 90.6% | |||

| Miehlke et al[110] | 2nd | OME 40 mg and AMO 750 mg qid for 14 d | 41 | 75.6% | 83.8% | |||

| Furuta et al[100] | 2nd | RAB 10 mg and AMO 500 mg qid for 14 d | 12 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100% | ||

| Furuta et al[111] | 2nd | LAN 30 mg and AMO 500 mg qid for 14 d | 32 | 96.9% | 95.7% | 100% | 100% | |

| Shirai et al[112] | 2nd | RAB 10 mg and AMO 500 mg qid | 66 | 90.9% | 93.8% | |||

| Graham et al[113] | 1st | ESO 40 mg and AMO 750 mg tid for 7 d | 36 | 72.2% | 74.2% | |||

| Kim et al[114] | 1st | LAN 30 mg and AMO 750 mg tid for 14 d | 104 | 67.3% | 78.4% | |||

| Goh et al[115] | 2nd | RAB 20 mg and AMO 1 g tid for 14 d | 149 | 71.8% | 75.4% | |||

Despite the advantage of the low resistance rate to amoxicillin, the eradication rate of high dose dual therapy has been found to vary in different studies. There have only been a few randomized, large scale prospective studies examining the efficacy, adverse events, and patient adherence of high dose dual therapy as first-line or rescue regimen for H. pylori eradication and more are required to explain the discrepancies in the eradication rate; factors to be considered may include intragastric pH and dose frequency. As described above, an intragastric pH of 5 or higher is important for treatment outcome, and this is controlled by a number of factors, including PPI dose frequency, CYP2C19 genotype, and IL-1β genotype. In addition, since the bactericidal effect of amoxicillin is time-dependent, the strategy for therapy is to increase duration of exposure, rather than increase the maximum concentration. Thus, for maximal pharmacodynamic effect, it is better to give amoxicillin in smaller and more frequent doses (e.g., 500 mg four times daily), rather than higher and less frequent doses. In this regard, an optimized high dose dual therapy (e.g., both PPI and amoxicillin given four times daily) has the potential to be used as first-line or rescue therapy for treatment of H. pylori infection. Alternatively, to improve patient compliance, sustained-release dosage forms could be used.

Eradication of H. pylori infection is important because of its high prevalence and implications in other diseases. Combinations of antisecretory agents and antimicrobial agents have been proposed as first-line or second-line therapy for its treatment. However, treatment outcome depends on many factors, including intragastric acidity and resistance to antimicrobial agents. While intragastric acidity can be controlled by PPIs, resistance to various antimicrobial agents is increasing. Of the antimicrobial agents frequently used to treat H. pylori infection, resistance to amoxicillin is generally low. Although dual therapy containing a PPI and amoxicillin has been reported to result in different eradication rates, its efficacy can be improved by adjusting the dose and dose frequency. In addition, although clinical use of alternative medicines has still to be evaluated, phytomedicines or probiotics may have the potential to provide additive or synergistic effects against H. pylori because they exert different effects. Further studies are required to examine the application of optimized high dose dual therapy and alternative medicines as first-line or rescue treatment for H. pylori infection.

P- Reviewers: Ananthakrishnan N, Chong VH, Jonaitis L, Sugimoto M S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3302] [Cited by in RCA: 3265] [Article Influence: 79.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Amieva MR, El-Omar EM. Host-bacterial interactions in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:306-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Scott D, Weeks D, Melchers K, Sachs G. The life and death of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1998;43 Suppl 1:S56-S60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brown LM. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:283-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vale FF, Vítor JM. Transmission pathway of Helicobacter pylori: does food play a role in rural and urban areas? Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;138:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Peura DA, Crowe CE. Helicobacter pylori. Feldman: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders 2010; 833-845. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Fock KM, Ang TL. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:479-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338:1175-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1293] [Cited by in RCA: 1201] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kuipers EJ. Helicobacter pylori and the risk and management of associated diseases: gastritis, ulcer disease, atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11 Suppl 1:71-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Sipponen P, Hyvärinen H. Role of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of gastritis, peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993;196:3-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3187] [Article Influence: 132.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Infection with Helicobacter pylori. In: IARC monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risks to humans. Vol. 61. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon, France: Interantional Agency for Research on Cancer 1994; 177-240. |

| 13. | Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, Ang TL, Hunt R, Talley NJ, Lam SK, Xiao SD, Tan HJ, Wu CY. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587-1600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | World Gastroenterology Organisation. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline: Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:383-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1719] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 122.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 16. | Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 819] [Cited by in RCA: 830] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Iwao E, Yokoyama Y, Yamamoto K, Hirayama F, Haga K. In vitro and in vivo anti- Helicobacter pylori activity of Y-904, a new fluoroquinolone. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Irie Y, Tateda K, Matsumoto T, Miyazaki S, Yamaguchi K. Antibiotic MICs and short time-killing against Helicobacter pylori: therapeutic potential of kanamycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hoffman PS, Goodwin A, Johnsen J, Magee K, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ. Metabolic activities of metronidazole-sensitive and -resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori: repression of pyruvate oxidoreductase and expression of isocitrate lyase activity correlate with resistance. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4822-4829. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Mégraud F, Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:280-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 27.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 3.1, 2013. Available from: http://www.eucast.org. |

| 22. | Craig WA. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1-10; quiz 11-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2187] [Cited by in RCA: 2204] [Article Influence: 81.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Berry V, Jennings K, Woodnutt G. Bactericidal and morphological effects of amoxicillin on Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1859-1861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Megraud F, Trimoulet pascale H, Boyanova L. Bactericidal effect of amoxicillin on Helicobacter pylori in an in vitro model using epithelial cells. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:869-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lambert JR, Midolo P. The actions of bismuth in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11 Suppl 1:27-33. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Sörberg M, Hanberger H, Nilsson M, Nilsson LE. Pharmacodynamic effects of antibiotics and acid pump inhibitors on Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2218-2223. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Davis R, Bryson HM. Levofloxacin. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1994;47:677-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dore MP, Osato MS, Realdi G, Mura I, Graham DY, Sepulveda AR. Amoxycillin tolerance in Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | van Zwet AA, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Thijs JC, van der Wouden EJ, Gerrits MM, Kusters JG. Stable amoxicillin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1998;352:1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kwon DH, Dore MP, Kim JJ, Kato M, Lee M, Wu JY, Graham DY. High-level beta-lactam resistance associated with acquired multidrug resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2169-2178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mégraud F. H pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance, and advances in testing. Gut. 2004;53:1374-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 32. | Cattoir V, Nectoux J, Lascols C, Deforges L, Delchier JC, Megraud F, Soussy CJ, Cambau E. Update on fluoroquinolone resistance in Helicobacter pylori: new mutations leading to resistance and first description of a gyrA polymorphism associated with hypersusceptibility. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:389-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Moore RA, Beckthold B, Wong S, Kureishi A, Bryan LE. Nucleotide sequence of the gyrA gene and characterization of ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:107-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Goodwin A, Kersulyte D, Sisson G, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Berg DE, Hoffman PS. Metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori is due to null mutations in a gene (rdxA) that encodes an oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitroreductase. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jenks PJ, Edwards DI. Metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kwon DH, El-Zaatari FA, Kato M, Osato MS, Reddy R, Yamaoka Y, Graham DY. Analysis of rdxA and involvement of additional genes encoding NAD(P)H flavin oxidoreductase (FrxA) and ferredoxin-like protein (FdxB) in metronidazole resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2133-2142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Heep M, Beck D, Bayerdörffer E, Lehn N. Rifampin and rifabutin resistance mechanism in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1497-1499. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Heep M, Rieger U, Beck D, Lehn N. Mutations in the beginning of the rpoB gene can induce resistance to rifamycins in both Helicobacter pylori and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1075-1077. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Suzuki S, Suzuki H, Nishizawa T, Kaneko F, Ootani S, Muraoka H, Saito Y, Kobayashi I, Hibi T. Past rifampicin dosing determines rifabutin resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Digestion. 2009;79:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Review article: rifabutin in the treatment of refractory Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:209-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lambert JR. Pharmacology of bismuth-containing compounds. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13 Suppl 8:S691-S695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Goodwin CS, Marshall BJ, Blincow ED, Wilson DH, Blackbourn S, Phillips M. Prevention of nitroimidazole resistance in Campylobacter pylori by coadministration of colloidal bismuth subcitrate: clinical and in vitro studies. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sachs G, Shin JM, Briving C, Wallmark B, Hersey S. The pharmacology of the gastric acid pump: the H+,K+ ATPase. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:277-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Besancon M, Simon A, Sachs G, Shin JM. Sites of reaction of the gastric H,K-ATPase with extracytoplasmic thiol reagents. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22438-22446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Huber R, Kohl B, Sachs G, Senn-Bilfinger J, Simon WA, Sturm E. Review article: the continuing development of proton pump inhibitors with particular reference to pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:363-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sohn DR, Kobayashi K, Chiba K, Lee KH, Shin SG, Ishizaki T. Disposition kinetics and metabolism of omeprazole in extensive and poor metabolizers of S-mephenytoin 4’-hydroxylation recruited from an Oriental population. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:1195-1202. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Yasuda S, Horai Y, Tomono Y, Nakai H, Yamato C, Manabe K, Kobayashi K, Chiba K, Ishizaki T. Comparison of the kinetic disposition and metabolism of E3810, a new proton pump inhibitor, and omeprazole in relation to S-mephenytoin 4’-hydroxylation status. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;58:143-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sohn DR, Kwon JT, Kim HK, Ishizaki T. Metabolic disposition of lansoprazole in relation to the S-mephenytoin 4’-hydroxylation phenotype status. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61:574-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tanaka M, Ohkubo T, Otani K, Suzuki A, Kaneko S, Sugawara K, Ryokawa Y, Hakusui H, Yamamori S, Ishizaki T. Metabolic disposition of pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, in relation to S-mephenytoin 4’-hydroxylation phenotype and genotype. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;62:619-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Sakai T, Aoyama N, Kita T, Sakaeda T, Nishiguchi K, Nishitora Y, Hohda T, Sirasaka D, Tamura T, Tanigawara Y. CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacokinetics of three proton pump inhibitors in healthy subjects. Pharm Res. 2001;18:721-727. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Tanaka M, Ohkubo T, Otani K, Suzuki A, Kaneko S, Sugawara K, Ryokawa Y, Ishizaki T. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, in extensive and poor metabolizers of S-mephenytoin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:108-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Abelö A, Andersson TB, Antonsson M, Naudot AK, Skånberg I, Weidolf L. Stereoselective metabolism of omeprazole by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:966-972. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Kang JM, Kim N, Lee DH, Park YS, Kim JS, Chang IJ, Song IS, Jung HC. Effect of the CYP2C19 polymorphism on the eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection by 7-day triple therapy with regular proton pump inhibitor dosage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1287-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Hunfeld NG, Touw DJ, Mathot RA, van Schaik RH, Kuipers EJ. A comparison of the acid-inhibitory effects of esomeprazole and rabeprazole in relation to pharmacokinetics and CYP2C19 polymorphism. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:810-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Product Information: DEXILANT(R) delayed release oral capsules, dexlansoprazole delayed release oral capsules. Deerfield, IL: Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc. 2010; . |

| 56. | Nakao M, Malfertheiner P. Growth inhibitory and bactericidal activities of lansoprazole compared with those of omeprazole and pantoprazole against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1998;3:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Kawakami Y, Akahane T, Yamaguchi M, Oana K, Takahashi Y, Okimura Y, Okabe T, Gotoh A, Katsuyama T. In vitro activities of rabeprazole, a novel proton pump inhibitor, and its thioether derivative alone and in combination with other antimicrobials against recent clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:458-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lin J, Huang WW. A systematic review of treating Helicobacter pylori infection with Traditional Chinese Medicine. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4715-4719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Vítor JM, Vale FF. Alternative therapies for Helicobacter pylori: probiotics and phytomedicine. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2011;63:153-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Yang JC, Shun CT, Chien CT, Wang TH. Effective prevention and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection using a combination of catechins and sialic acid in AGS cells and BALB/c mice. J Nutr. 2008;138:2084-2090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Yang JC, Yang HC, Shun CT, Wang TH, Chien CT, Kao JY. Catechins and Sialic Acid Attenuate Helicobacter pylori-Triggered Epithelial Caspase-1 Activity and Eradicate Helicobacter pylori Infection. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:248585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Cremonini F, Di Caro S, Covino M, Armuzzi A, Gabrielli M, Santarelli L, Nista EC, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Effect of different probiotic preparations on anti-helicobacter pylori therapy-related side effects: a parallel group, triple blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2744-2749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Cindoruk M, Erkan G, Karakan T, Dursun A, Unal S. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in the 14-day triple anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Helicobacter. 2007;12:309-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Hurduc V, Plesca D, Dragomir D, Sajin M, Vandenplas Y. A randomized, open trial evaluating the effect of Saccharomyces boulardii on the eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Armuzzi A, Cremonini F, Bartolozzi F, Canducci F, Candelli M, Ojetti V, Cammarota G, Anti M, De Lorenzo A, Pola P. The effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus GG on antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal side-effects during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Canducci F, Armuzzi A, Cremonini F, Cammarota G, Bartolozzi F, Pola P, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. A lyophilized and inactivated culture of Lactobacillus acidophilus increases Helicobacter pylori eradication rates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Sachdeva A, Nagpal J. Effect of fermented milk-based probiotic preparations on Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. A report card to grade Helicobacter pylori therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:275-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 70. | Furuta T, Shirai N, Kodaira M, Sugimoto M, Nogaki A, Kuriyama S, Iwaizumi M, Yamade M, Terakawa I, Ohashi K. Pharmacogenomics-based tailored versus standard therapeutic regimen for eradication of H. pylori. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;81:521-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Zullo A, Rinaldi V, Winn S, Meddi P, Lionetti R, Hassan C, Ripani C, Tomaselli G, Attili AF. A new highly effective short-term therapy schedule for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:715-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Zullo A, Vaira D, Vakil N, Hassan C, Gatta L, Ricci C, De Francesco V, Menegatti M, Tampieri A, Perna F. High eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori with a new sequential treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:719-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069-379; quiz 1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Greenberg ER, Anderson GL, Morgan DR, Torres J, Chey WD, Bravo LE, Dominguez RL, Ferreccio C, Herrero R, Lazcano-Ponce EC. 14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in seven Latin American sites: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378:507-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Okada M, Oki K, Shirotani T, Seo M, Okabe N, Maeda K, Nishimura H, Ohkuma K, Oda K. A new quadruple therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Effect of pretreatment with omeprazole on the cure rate. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:640-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Treiber G, Ammon S, Schneider E, Klotz U. Amoxicillin/metronidazole/omeprazole/clarithromycin: a new, short quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 1998;3:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Essa AS, Kramer JR, Graham DY, Treiber G. Meta-analysis: four-drug, three-antibiotic, non-bismuth-containing “concomitant therapy” versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2009;14:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, Opekun AR, Kuo CH, Wu IC, Wang SS, Chen A, Hung WC, Graham DY. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36-41.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Cammarota G, Cianci R, Cannizzaro O, Cuoco L, Pirozzi G, Gasbarrini A, Armuzzi A, Zocco MA, Santarelli L, Arancio F. Efficacy of two one-week rabeprazole/levofloxacin-based triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1339-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Liou JM, Lin JT, Chang CY, Chen MJ, Cheng TY, Lee YC, Chen CC, Sheng WH, Wang HP, Wu MS. Levofloxacin-based and clarithromycin-based triple therapies as first-line and second-line treatments for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomised comparative trial with crossover design. Gut. 2010;59:572-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Yang JC, Lin CJ. CYP2C19 genotypes in the pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of proton pump inhibitor-based therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6:29-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Yang JC, Wang HL, Chern HD, Shun CT, Lin BR, Lin CJ, Wang TH. Role of omeprazole dosage and cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype in patients receiving omeprazole-amoxicillin dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:227-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, Kajimura M, Hishida A, Sakurai M, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T. Different dosage regimens of rabeprazole for nocturnal gastric acid inhibition in relation to cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype status. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:290-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Sugimoto M, Shirai N, Nishino M, Kodaira C, Uotani T, Yamade M, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Sugimoto K, Miyajima H. Rabeprazole 10 mg q.d.s. decreases 24-h intragastric acidity significantly more than rabeprazole 20 mg b.d. or 40 mg o.m., overcoming CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:627-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Hwang IR, Kodama T, Kikuchi S, Sakai K, Peterson LE, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. Effect of interleukin 1 polymorphisms on gastric mucosal interleukin 1beta production in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1793-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Furuta T, Shirai N, Xiao F, El-Omar EM, Rabkin CS, Sugimura H, Ishizaki T, Ohashi K. Polymorphism of interleukin-1beta affects the eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori by triple therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:22-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, Ikuma M, Hishida A, Ishizaki T. Influences of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine polymorphisms on eradication rates of clarithromycin-sensitive strains of Helicobacter pylori by triple therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:41-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Horiki N, Omata F, Uemura M, Suzuki S, Ishii N, Iizuka Y, Fukuda K, Fujita Y, Katsurahara M, Ito T. Annual change of primary resistance to clarithromycin among Helicobacter pylori isolates from 1996 through 2008 in Japan. Helicobacter. 2009;14:86-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Ierardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-414. [PubMed] |

| 90. | Wu W, Yang Y, Sun G. Recent Insights into Antibiotic Resistance in Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:723183. [PubMed] |

| 91. | Glupczynski Y, Mégraud F, Lopez-Brea M, Andersen LP. European multicentre survey of in vitro antimicrobial resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:820-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, Kist M, Lopez-Brea M, Hirschl AM, Andersen LP, Goossens H, Glupczynski Y. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut. 2013;62:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 632] [Article Influence: 52.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 93. | Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple first-line therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:343-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Frenck RW, Clemens J. Helicobacter in the developing world. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:705-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Gao W, Cheng H, Hu F, Li J, Wang L, Yang G, Xu L, Zheng X. The evolution of Helicobacter pylori antibiotics resistance over 10 years in Beijing, China. Helicobacter. 2010;15:460-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Murakami K, Fujioka T, Okimoto T, Sato R, Kodama M, Nasu M. Drug combinations with amoxycillin reduce selection of clarithromycin resistance during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Toracchio S, Marzio L. Primary and secondary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated in central Italy during the years 1998-2002. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:541-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Unge P, Gad A, Gnarpe H, Olsson J. Does omeprazole improve antimicrobial therapy directed towards gastric Campylobacter pylori in patients with antral gastritis? A pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;167:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Bayerdörffer E, Miehlke S, Mannes GA, Sommer A, Höchter W, Weingart J, Heldwein W, Klann H, Simon T, Schmitt W. Double-blind trial of omeprazole and amoxicillin to cure Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcers. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1412-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Furuta T, Shirai N, Takashima M, Xiao F, Hanai H, Nakagawa K, Sugimura H, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T. Effects of genotypic differences in CYP2C19 status on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection by dual therapy with rabeprazole plus amoxicillin. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:341-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Asrat D, Kassa E, Mengistu Y, Nilsson I, Wadström T. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from adult dyspeptic patients in Tikur Anbassa University Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2004;42:79-85. [PubMed] |

| 102. | Chung JW, Lee GH, Jeong JY, Lee SM, Jung JH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Jung HY, Kim JH. Resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains to antibiotics in Korea with a focus on fluoroquinolone resistance. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:493-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Reyes G, Mulder J, aan de Stegge BM, Peters JT, Savelkoul PH, Tanca J, Peña AS, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. Characteristics of clinical Helicobacter pylori strains from Ecuador. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:141-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Lwai-Lume L, Ogutu EO, Amayo EO, Kariuki S. Drug susceptibility pattern of Helicobacter pylori in patients with dyspepsia at the Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2005;82:603-608. [PubMed] |

| 105. | Mendonça S, Ecclissato C, Sartori MS, Godoy AP, Guerzoni RA, Degger M, Pedrazzoli J. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, amoxicillin, tetracycline, and furazolidone in Brazil. Helicobacter. 2000;5:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Ndip RN, Malange Takang AE, Ojongokpoko JE, Luma HN, Malongue A, Akoachere JF, Ndip LM, MacMillan M, Weaver LT. Helicobacter pylori isolates recovered from gastric biopsies of patients with gastro-duodenal pathologies in Cameroon: current status of antibiogram. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:848-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Sherif M, Mohran Z, Fathy H, Rockabrand DM, Rozmajzl PJ, Frenck RW. Universal high-level primary metronidazole resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolated from children in Egypt. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4832-4834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Smith SI, Oyedeji KS, Arigbabu AO, Atimomo C, Coker AO. High amoxycillin resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolated from gastritis and peptic ulcer patients in western Nigeria. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:67-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Tanih NF, Okeleye BI, Naidoo N, Clarke AM, Mkwetshana N, Green E, Ndip LM, Ndip RN. Marked susceptibility of South African Helicobacter pylori strains to ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin: clinical implications. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:49-52. [PubMed] |

| 110. | Miehlke S, Kirsch C, Schneider-Brachert W, Haferland C, Neumeyer M, Bästlein E, Papke J, Jacobs E, Vieth M, Stolte M. A prospective, randomized study of quadruple therapy and high-dose dual therapy for treatment of Helicobacter pylori resistant to both metronidazole and clarithromycin. Helicobacter. 2003;8:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Furuta T, Shirai N, Takashima M, Xiao F, Hanai H, Sugimura H, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T, Kaneko E. Effect of genotypic differences in CYP2C19 on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection by triple therapy with a proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:158-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Shirai N, Sugimoto M, Kodaira C, Nishino M, Ikuma M, Kajimura M, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T, Hishida A, Furuta T. Dual therapy with high doses of rabeprazole and amoxicillin versus triple therapy with rabeprazole, amoxicillin, and metronidazole as a rescue regimen for Helicobacter pylori infection after the standard triple therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:743-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Graham DY, Javed SU, Keihanian S, Abudayyeh S, Opekun AR. Dual proton pump inhibitor plus amoxicillin as an empiric anti-H. pylori therapy: studies from the United States. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:816-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Kim SY, Jung SW, Kim JH, Koo JS, Yim HJ, Park JJ, Chun HJ, Lee SW, Choi JH. Effectiveness of three times daily lansoprazole/amoxicillin dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73:140-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Goh KL, Manikam J, Qua CS. High-dose rabeprazole-amoxicillin dual therapy and rabeprazole triple therapy with amoxicillin and levofloxacin for 2 weeks as first and second line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori treatment failures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;Mar 8; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |