Published online May 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5165

Revised: February 24, 2014

Accepted: March 4, 2014

Published online: May 7, 2014

Processing time: 236 Days and 20.3 Hours

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) can occur in lymphoma patients infected with HBV when they receive chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Prophylactic administration of lamivudine (LAM) reduces the morbidity and mortality associated with HBV reactivation. However, what defines HBV reactivation and the optimal duration of treatment with LAM have not yet been clearly established. HBV reactivation may occur due to the cessation of prophylactic LAM, although re-treatment with nucleoside analogs may sometimes result in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroconversion, which is a satisfactory endpoint for the management of HBV infection. We report a case of HBV reactivation in a 68-year-old HBsAg-positive patient who received rituximab-based immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma. HBV reactivation developed following cessation of prophylactic LAM therapy. The patient subsequently received treatment with entecavir (ETV), which led to a rapid and sustained suppression of HBV replication and HBsAg seroconversion. We also appraised the literature concerning HBV reactivation and the role of ETV in the management of HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients. A total of 28 cases of HBV reactivation have been reported as having been treated with ETV during or after immunosuppressive chemotherapy in lymphoma patients. We conclude that ETV is an efficacious and safe treatment for HBV reactivation following LAM cessation in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-based immunochemotherapy.

Core tip: We describe the case of a 68-year-old hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive male patient who received rituximab-based immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma, and experienced hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation following cessation of lamivudine prophylaxis. Subsequent entecavir treatment produced rapid, sustained viral suppression and HBsAg seroconversion. Lamivudine prevents HBV reactivation but resistance rates may be as high as 17% in lymphoma patients. Available data suggest that entecavir is effective and safe for the treatment of HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients. Prophylactic antiviral therapy is recommended for patients with active or occult HBV infection following chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy. Potent antiviral drugs with a high genetic barrier to resistance should be considered in these cases.

- Citation: Liu WP, Zheng W, Song YQ, Ping LY, Wang GQ, Zhu J. Hepatitis B surface antigen seroconversion after HBV reactivation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(17): 5165-5170

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i17/5165.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5165

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is highly prevalent in many malignancies, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)[1,2]. In recent years, rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen on B cells, has greatly improved the prognosis and outcome of patients with NHL[3,4]. However, rituximab induced profound and persistent depletion of the circulating population of B cells, leading to dysregulation of host immunity to HBV and increased risk of HBV reactivation[5,6]. Consequently, viral reactivation is an area of concern whenever an HBV-positive patient receives chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy[7]. Prophylactic administration of antiviral agents may reduce the incidence of HBV reactivation but flares do occur in 60% of patients following discontinuation of antiviral treatment[8]. We report a case of HBV reactivation following cessation of prophylactic lamivudine (LAM) in a patient with NHL who received rituximab-based treatment. Early administration of entecavir (ETV) successfully prevented further progression of HBV infection, leading to hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroconversion.

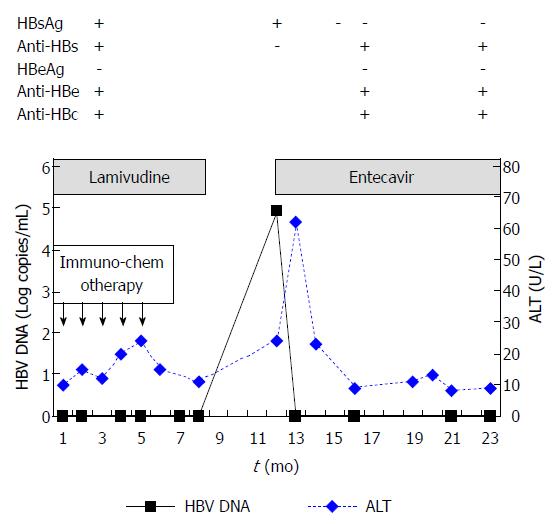

A 68-year-old male was admitted to our hospital for follicular lymphoma in March 2009. He had chronic HBV infection for more than two decades. On admission, his alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were within the upper limit of normal (< 40 U/L). The patient’s serology was found to be positive for HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs), hepatitis B envelope antibody (anti-HBe), and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc). However, he was HBeAg-negative. His HBsAg and anti-HBs titers were > 250 IU/mL and 45.81 mIU/mL, respectively, as measured by chemiluminescence microparticle immunoassays. His serum HBV DNA concentration was undetectable (limit of detection by polymerase chain reaction: 1000 copies/mL). The time course of the levels of liver enzymes and HBV DNA is shown in Figure 1.

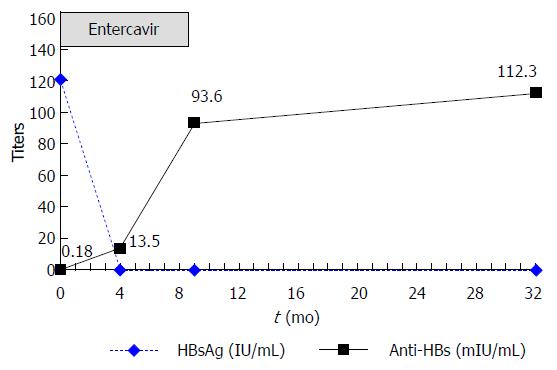

From March 2009 to July 2009, administration of 5 cycles of immunochemotherapy (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide) led to partial remission of the patient’s lymphoma. No additional treatment with anticancer drugs or corticosteroids followed. Prophylactic LAM (100 mg daily) was administered on the first day of immunochemotherapy and continued for 4 mo after completion of immunochemotherapy (total: 8 mo). In February 2010, 3 mo following cessation of LAM therapy, the patient’s HBV DNA level rose to 8.15 × 104 copies/mL. His ALT, HBsAg, and anti-HBs levels were 24 U/L, 121 IU/mL and 0.18 mIU/mL, respectively. Reactivation of HBV infection was considered and antiviral treatment with ETV 0.5 mg daily was administered immediately. In March 2010, 1 mo after ETV initiation and while still receiving ETV therapy, the patient’s HBV DNA concentration fell below detectable levels, while his ALT level increased to 62 U/L. In April 2010, 2 mo after ETV initiation, the patient achieved clearance of HBsAg and normalization of ALT levels. In July 2010, 4 mo after ETV initiation, the patient became anti-HBs-positive (titer: 13.5 mIU/mL), indicating HBsAg seroconversion. In December 2010, 7 mo after HBsAg seroconversion, ETV treatment was stopped (total: 10 mo). In March 2011 (4 mo after discontinuing ETV treatment), his HBsAg level was still negative and the patient’s anti-HBs titer had increased to 93.6 mIU/mL. The patient’s ALT levels remained normal and his HBV DNA level was undetectable. Until September 2012, 21 mo after ETV discontinuation, his HBsAg level remained negative and the patient’s anti-HBs titer had increased to 112.3 mIU/mL (Figure 2). His ALT levels also remained normal, while the HBV DNA concentration was undetectable at the patient’s last two visits (Figure 1). Administration of ETV was well tolerated throughout the treatment period.

The nucleoside analog ETV provides the advantage of a higher genetic barrier to resistance than LAM for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B[9]. ETV has also been used to prevent HBV reactivation during chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy, although this experience is limited[10]. Several studies have examined the use of ETV in the treatment of HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients and suggest its effectiveness and safety[11-13]. A total of 28 cases of HBV reactivation reported in the literature involved ETV administration during or after immunosuppressive chemotherapy in patients with lymphoma (Table 1). Nine cases of HBV reactivation developed during chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy[11-17], while the remaining cases occurred after chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy[11,14,18-22]. Twenty-four patients received rituximab-based immunochemotherapy regimens[12-22]. Five patients died of hepatic failure following HBV reactivation[11,15,17,20,22], 4 of whom received rituximab-based regimens[15,17,20,22]. Clearance of HBsAg was observed in only 5 patients[11,19,21]. LAM was administered with the intention of preventing HBV reactivation in 4 patients from 2 different studies[11,18]. Of these, 3[18] developed HBV reactivation-related hepatitis 2-4 mo after discontinuation of LAM while the remaining case of HBV reactivation occurred 8 mo after cessation of LAM treatment[11].

| Author | Patients (n) | Hematologic malignancy | Pre-treatment HBV markers | Prophylaxis with anti-viral drugs | Rituximab-based regimen | Time of HBV reactivation (during/after anti-tumor therapy) | Outcome (alive/died) | HBsAg clearance (yes/no) |

| Ferreira et al[22] | 1 | DLBCL | HBsAg-, anti-HBs+, anti-HBc- | No | Yes | 0/1 | 0/1 | NR |

| Niitsu et al[14] | 6 | DLBCL | HBsAg- | No | Yes | 2/4 | 5/11 | NR |

| Chung et al[15] | 1 | DLBCL | HBsAg-, anti-HBs+, anti-HBc+ | No | Yes | 1/0 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| Lee et al[16] | 1 | FL | HBsAg-, anti-HBs+ | No | Yes | 1/0 | 1/0 | NR |

| Stange et al[17] | 2 | B cell lymphoma | unknown | No | Yes | 2/0 | 1/1 | NR |

| Brost et al[11] | 4 | AML and lymphoma | Unknown for all | 1 Yes, 3 No | No | 2/2 | 3/1 | 3/1 |

| Sanchez et al[12] | 1 | CLL | HBsAg- | No | Yes | 0/1 | 1/0 | NR |

| Colson et al[13] | 1 | B cell lymphoma | HBsAg-, anti-HBs-, anti-HBc+ | No | Yes | 1/0 | 1/0 | NR |

| Mimura et al[18] | 3 | B cell lymphoma | HBsAg+ | Yes | Yes | 0/3 | 3/0 | NR |

| Matsue et al[19] | 5 | B cell lymphoma | HBsAg- | No | Yes | 0/5 | 5/0 | 1/4 |

| Wu et al[20] | 1 | DLBCL | HBsAg-, anti-HBc+ | No | Yes | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| Fukushima et al[21] | 2 | NHL, DLBCL | HBsAg- | No | Yes | 0/2 | 2/0 | 1/1 |

Malignant lymphoma is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, despite the fact that the long-term prognosis of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma has improved following the introduction of immunochemotherapeutic agents, such as rituximab[23]. The occurrence of HBV infection has been associated with lymphoma and hepatocellular carcinoma[24]. In addition, reactivation of HBV may be a fatal complication in patients with HBV infection who receive immunochemotherapy for lymphoma, especially rituximab-based regimens. While the exact definition of HBV reactivation differs among investigators[25], reactivation of HBV is deemed to occur in both HBsAg-positive or -negative patients. Among patients who only present with anti-HBc antibody-positive serology, the risk factors for HBV reactivation include male gender and low anti-HBs titer[14].

Given the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with HBV reactivation and hepatitis flares, prophylactic antiviral therapy should be administered to HBsAg-positive cancer patients if they receive immunochemotherapy. LAM has been shown to be clinically effective in reducing the incidence and severity of HBV reactivation, but treatment guidelines differ in their recommendations for prophylactic antiviral therapy[26-28]. In addition, the optimal duration of prophylactic LAM therapy has not yet been clearly established. For instance, the incidence of YMDD mutation and HBV reactivation following withdrawal of LAM in patients with NHL were similar to that for patients with chronic hepatitis B. In a long-term study, 17% of HBsAg-positive NHL patients developed YMDD mutation during LAM therapy (median duration: 11.5 mo), and 4% developed HBV reactivation following LAM withdrawal[29]. In one prospective study, 23.9% of 46 patients with hematological malignancies developed HBV reactivation after withdrawal of LAM prophylaxis[30]. HBV reactivation was more likely to develop in patients with elevated HBV DNA levels prior to chemotherapy. A prolonged administration of antiviral therapy may be necessary in these patients; however, drug resistance must be considered. ETV may be the preferred drug because of its high antiviral potency and high barrier to resistance. In a retrospective study, ETV showed a very low rate of prophylaxis failure. HBV reactivation was not detected in 31 HBsAg-positive patients treated with ETV prophylaxis (median duration: 17 mo)[31]. A randomized controlled trial confirmed that ETV prophylaxis until 3 mo after completion of chemotherapy was insufficient even in patients with undetectable hepatitis B. One of the 41 patients in the ETV prophylaxis group had delayed HBV reactivation, almost 7 mo after discontinuing ETV prophylaxis. Therefore, it is important to routinely monitor HBV DNA levels after discontinuation of ETV[32].

In a community-based follow-up study, spontaneous clearance of HBsAg from serum occurred in 562 chronic hepatitis B patients during 24829 person-years of follow-up evaluation, resulting in an overall annual seroclearance rate of 2.26%[33]. The levels of HBV DNA at baseline and follow-up evaluation were the most significant predictor of HBsAg seroclearance[34]. To our knowledge, there has been no report to date of spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance following HBV reactivation. It is therefore unclear whether the HBsAg seroconversion observed in our patient could be attributed to the ETV treatment or considered spontaneous.

In conclusion, prophylactic antiviral therapy is highly recommended in patients with active or occult HBV infection who receive chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy. In the event of HBV reactivation at the time HBV prophylaxis is stopped, administration of a potent antiviral agent with a high genetic barrier to resistance should be considered.

The authors thank Timothy Stentiford from MediTech Media Asia Pacific for providing editorial assistance on this manuscript. Editorial assistance was supported by the Bristol Myers Squibb Company.

A 68-year-old patient was admitted to hospital for follicular lymphoma, with a 2-decade history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. He received rituximab-based immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma and experienced HBV reactivation following cessation of lamivudine prophylaxis.

The patient had no symptoms or signs when HBV reactivation occurred.

Hepatitis due to drugs, alcoholic hepatitis, and other factors were excluded.

After cessation of lamivudine (LAM) prophylaxis, the patient’s HBV DNA (by polymerase chain reaction) rose to 8.15 × 104 copies/mL from an undetectable baseline level, followed by elevated alanine aminotransferase.

The patient received entecavir (ETV) 0.5 mg/d for 10 mo and experienced sustained viral suppression with HBsAg seroconversion.

ETV provides the advantage of a higher genetic barrier to resistance than LAM for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Several studies examining the use of ETV for treating HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients suggest that it is a safe and effective therapy.

HBV reactivation was defined as a tenfold increase in HBV DNA level or the reappearance of detectable HBV DNA.

Prophylactic antiviral therapy is highly recommended in patients with active or occult HBV infection who receive chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy; a potent antiviral agent with a high genetic barrier to resistance should be considered.

This case reports the relatively uncommon finding of hepatitis B surface antigen seroconversion following ETV therapy in a lymphoma patient with chronic HBV who experienced HBV reactivation following rituximab-based immunochemotherapy. It is well written.

P- Reviewers: Arai M, Jin B, Said ZNA, Senturk H S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Nath A, Agarwal R, Malhotra P, Varma S. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intern Med J. 2010;40:633-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Michielsen P, Ho E. Viral hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:4-8. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, Marit G, Macro M, Sebban C. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d’Etudes des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood. 2010;116:2040-2045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1132] [Article Influence: 75.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, Osterborg A, Trneny M, Shepherd L, Gill DS, Walewski J, Pettengell R, Jaeger U. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1013-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 575] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mastroianni CM, Lichtner M, Citton R, Del Borgo C, Rago A, Martini H, Cimino G, Vullo V. Current trends in management of hepatitis B virus reactivation in the biologic therapy era. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3881-3887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dong HJ, Ni LN, Sheng GF, Song HL, Xu JZ, Ling Y. Risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving rituximab-chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koo YX, Tan DS, Tan IB, Tao M, Chow WC, Lim ST. Hepatitis B virus reactivation and role of antiviral prophylaxis in lymphoma patients with past hepatitis B virus infection who are receiving chemoimmunotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim YM, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Lee SH, Hwang JH, Park YS, Kim N, Lee JS, Kim HY, Lee DH. Chronic hepatitis B, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and effect of prophylactic antiviral therapy. J Clin Virol. 2011;51:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wong VW, Wong GL, Yiu KK, Chim AM, Chu SH, Chan HY, Sung JJ, Chan HL. Entecavir treatment in patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2011;54:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Watanabe M, Shibuya A, Takada J, Tanaka Y, Okuwaki Y, Minamino T, Hidaka H, Nakazawa T, Koizumi W. Entecavir is an optional agent to prevent hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation: a review of 16 patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2010;21:333-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Brost S, Schnitzler P, Stremmel W, Eisenbach C. Entecavir as treatment for reactivation of hepatitis B in immunosuppressed patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5447-5451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sanchez MJ, Buti M, Homs M, Palacios A, Rodriguez-Frias F, Esteban R. Successful use of entecavir for a severe case of reactivation of hepatitis B virus following polychemotherapy containing rituximab. J Hepatol. 2009;51:1091-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Colson P, Borentain P, Coso D, Chabannon C, Tamalet C, Gérolami R. Entecavir as a first-line treatment for HBV reactivation following polychemotherapy for lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:148-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Niitsu N, Hagiwara Y, Tanae K, Kohri M, Takahashi N. Prospective analysis of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma after rituximab combination chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5097-5100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Chung SM, Sohn JH, Kim TY, Yoo KD, Ahn YW, Bae JH, Jeon YC, Choi JH. [Fulminant hepatic failure with hepatitis B virus reactivation after rituximab treatment in a patient with resolved hepatitis B]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:266-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee IC, Huang YH, Chu CJ, Lee PC, Lin HC, Lee SD. Hepatitis B virus reactivation after 23 months of rituximab-based chemotherapy in an HBsAg-negative, anti-HBs-positive patient with follicular lymphoma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73:156-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stange MA, Tutarel O, Pischke S, Schneider A, Strassburg CP, Becker T, Barg-Hock H, Bastürk M, Wursthorn K, Cornberg M. Fulminant hepatic failure due to chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B reactivation: role of rituximab. Z Gastroenterol. 2010;48:258-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mimura N, Tsujimura H, Ise M, Sakai C, Kojima H, Fukai K, Yokosuka O, Takagi T, Kumagai K. [Hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of prophylactic lamivudine therapy in B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab combined CHOP therapy]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2009;50:1715-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Matsue K, Kimura S, Takanashi Y, Iwama K, Fujiwara H, Yamakura M, Takeuchi M. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus after rituximab-containing treatment in patients with CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 2010;116:4769-4776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wu JM, Huang YH, Lee PC, Lin HC, Lee SD. Fatal reactivation of hepatitis B virus in a patient who was hepatitis B surface antigen negative and core antibody positive before receiving chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:496-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fukushima N, Mizuta T, Tanaka M, Yokoo M, Ide M, Hisatomi T, Kuwahara N, Tomimasu R, Tsuneyoshi N, Funai N. Retrospective and prospective studies of hepatitis B virus reactivation in malignant lymphoma with occult HBV carrier. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:2013-2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ferreira R, Carvalheiro J, Torres J, Fernandes A, Giestas S, Mendes S, Agostinho C, Campos MJ. Fatal hepatitis B reactivation treated with entecavir in an isolated anti-HBs positive lymphoma patient: a case report and literature review. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:277-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu ZL, Song YQ, Shi YF, Zhu J. High nuclear expression of STAT3 is associated with unfavorable prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Engels EA, Cho ER, Jee SH. Hepatitis B virus infection and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in South Korea: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:827-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Torres HA, Davila M. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:156-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2168] [Article Influence: 135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2398] [Article Influence: 184.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T, Chan H, Chien RN, Liu CJ, Gane E, Locarnini S, Lim SG, Han KH. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531–561. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 742] [Cited by in RCA: 788] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim JS, Hahn JS, Park SY, Kim Y, Park IH, Lee CK, Cheong JW, Lee ST, Min YH. Long-term outcome after prophylactic lamivudine treatment on hepatitis B virus reactivation in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:78-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hui CK, Cheung WW, Au WY, Lie AK, Zhang HY, Yueng YH, Wong BC, Leung N, Kwong YL, Liang R. Hepatitis B reactivation after withdrawal of pre-emptive lamivudine in patients with haematological malignancy on completion of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gut. 2005;54:1597-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kim SJ, Hsu C, Song YQ, Tay K, Hong XN, Cao J, Kim JS, Eom HS, Lee JH, Zhu J. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in B-cell lymphoma patients treated with rituximab: analysis from the Asia Lymphoma Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3486-3496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Huang YH, Hsiao LT, Hong YC, Chiou TJ, Yu YB, Gau JP, Liu CY, Yang MH, Tzeng CH, Lee PC. Randomized controlled trial of entecavir prophylaxis for rituximab-associated hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with lymphoma and resolved hepatitis B. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2765-2772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Liu J, Yang HI, Lee MH, Lu SN, Jen CL, Wang LY, You SL, Iloeje UH, Chen CJ. Incidence and determinants of spontaneous hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance: a community-based follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:474-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Yang HI, Hung HL, Lee MH, Liu J, Jen CL, Su J, Wang LY, Lu SN, You SL, Iloeje UH. Incidence and determinants of spontaneous seroclearance of hepatitis B e antigen and DNA in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:527-534.e1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |