Published online May 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5157

Revised: December 22, 2013

Accepted: January 20, 2014

Published online: May 7, 2014

Processing time: 211 Days and 23.2 Hours

To investigate the clinical and computed tomography (CT) features of desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), we retrospectively analyzed the clinical presentations, treatment and outcome, as well as CT manifestations of four cases of DSRCT confirmed by surgery and pathology. The CT manifestations of DSRCT were as follows: (1) multiple soft-tissue masses or diffuse peritoneal thickening in the abdomen and pelvis, with the dominant mass usually located in the pelvic cavity; (2) masses without an apparent organ-based primary site; (3) mild to moderate homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement in solid area on enhanced CT; and (4) secondary manifestations, such as ascites, hepatic metastases, lymphadenopathy, hydronephrosis and hydroureter. The prognosis and overall survival rates were generally poor. Commonly used treatment strategies including aggressive tumor resection, polychemotherapy, and radiotherapy, showed various therapeutic effects. CT of DSRCT shows characteristic features that are helpful in diagnosis. Early discovery and complete resection, coupled with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, are important for prognosis of DSRCT. Whole abdominopelvic rather than locoregional radiotherapy is more effective for unresectable DSRCT.

Core tip: Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a rare abdominopelvic malignancy with multicentric growth. The third decade may be a peak period of incidence, and the disease can also occur in older people. Computed tomography can display characteristic features that are helpful in diagnosis of DSRCT. Prognosis and overall survival rates are generally poor. Early discovery and complete resection, coupled with postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, are important for prognosis of DSRCT. Whole abdominopelvic rather than locoregional radiotherapy is more effective for unresectable DSRCT.

- Citation: Shen XZ, Zhao JG, Wu JJ, Liu F. Clinical and computed tomography features of adult abdominopelvic desmoplastic small round cell tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(17): 5157-5164

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i17/5157.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5157

Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a rare and highly aggressive malignancy with poor prognosis, which was first described by Gerald et al[1] in 1989. Since then, more then 200 cases have been reported in the literature, and nearly one-third of them have been reported in the radiological literature. DSRCT primarily occurs in adolescents and young adults aged 15-25 years and develops in the abdominopelvic cavity with metastases commonly found in the peritoneum, liver, and lymphoid tissues. There is a strong male predilection, with male/female ratios ranging from 3:1 to 9:1[2-5]. Clinical presentations are notoriously nonspecific. Vague abdominal pain or discomfort, abdominal distension, change in bowel habits, and palpable abdominal mass are common[3-7]. Most patients are diagnosed in the advanced stages and have a poor prognosis. Bulky peritoneal soft-tissue masses without an apparent organ-based primary site are the imaging characteristics of abdominopelvic DSRCT.

Here, we report the appearance on computed tomography (CT) and the clinical features of four patients (two men and two women; age range, 24-64 years; mean, 35.5 years) with abdominopelvic DSRCT. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital, which waived the need for informed consent.

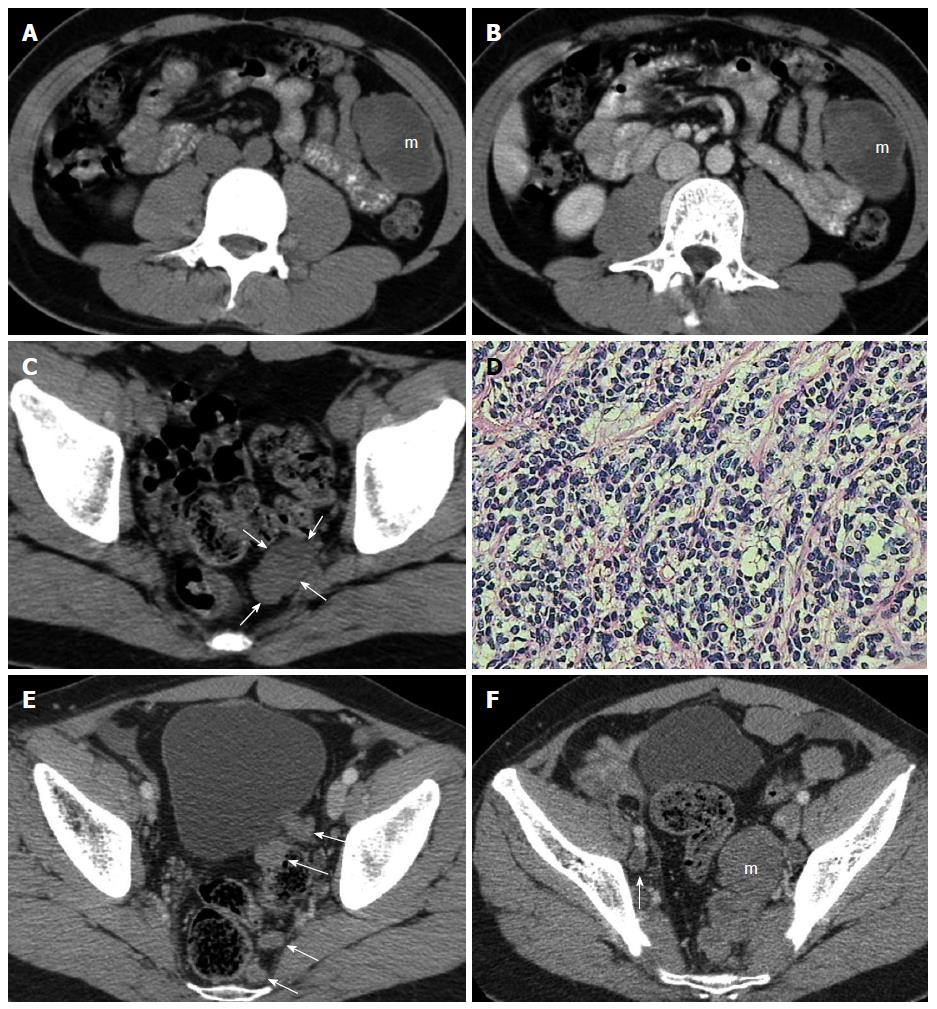

A 26-year-old man had a hypoechoic mass with an echoless area in the left mid-abdomen upon ultrasound (US) examination. On subsequent abdominal and pelvic CT, a 40 mm × 60 mm, well-defined, solid cystic tumor was discovered in the corresponding area (Figure 1A and B). A 24 mm × 27 mm soft tissue mass located on the left side of the pelvic cavity near the rectum was also found (Figure 1C). The pelvic mass, as well as the solid area of the left mid-abdominal mass, showed slight enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT (Figure 1B). The patient underwent resection of the abdominal and pelvic tumors, which were found to have arisen from the greater omentum and peritoneum, respectively. The two masses were subjected to histopathological examination. Microscopic evaluation showed that the tumor cells were small and round with hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm (Figure 1D), and immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD99, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), chromogranin A (CgA), neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and vimentin (Vim). The above features were compatible with DSRCT.

During the subsequent postoperative 6 mo, chemotherapy consisting of ifosfamide, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and diamminedichloroplatinum (IEP) was administered for six cycles. The patient was discharged from hospital after recovery.

Thirty-three months after surgery, follow-up CT showed a solitary, slightly enlarged pelvic lymph node and multiple homogeneous tumor nodules reappearing in the retrovesical and pararectal regions (Figure 1E). Six months later, CT showed that the pelvic tumor nodules had enlarged rapidly, forming a multinodular confluent tumor (Figure 1F). The patient died of serious complications caused by recurrence and metastases 42 mo after surgery.

A 28-year-old woman presented to our emergency department complaining of persistent pain in the right lower abdomen for 2 d, and the pain became worse for 1 d and slight fever developed. Physical examination revealed a large pelvic non-tender mass. US and CT showed a 150 mm × 120 mm solid-cystic mass located in the pelvis and the right lower abdomen, with a small amount of ascites. The solid area of the tumor showed slight enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT. The tumor was considered to be ovarian cancer by US and CT, and total hysterectomy and bilateral adnexectomy were performed. During the operation, a large mass was found originating from the right broad ligament, and several 20 mm × 20 mm nodules were discovered in the rectouterine space and greater omentum. Acute appendicitis with yellow to tan exudate and hyperemia was seen at the same time. Intraperitoneal perfusion chemotherapy with 20 mg nitrogen mustard was administered before closing the abdomen.

Histopathological evaluation of the excised tumor and nodules showed sheets and clusters of well-demarcated nests of tumor cells with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage. The cells were small and monomorphic with hyperchromatic nuclei, and the immunohistochemical stain was positive for cytokeratin (CK), CD99, EMA, NSE, and desmin. The disease was ultimately diagnosed as DSRCT.

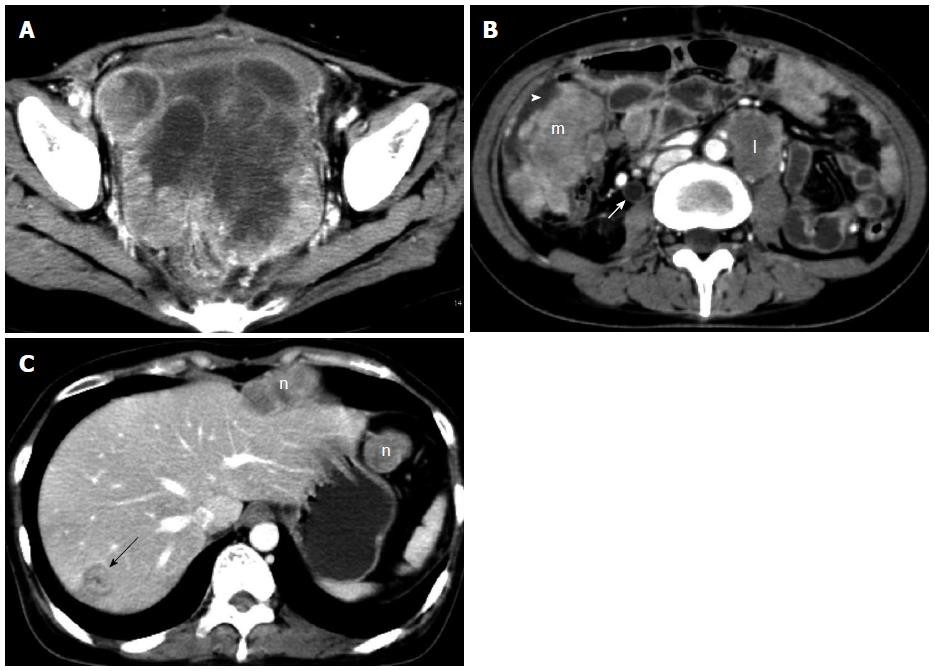

After surgery, she was treated with CAP chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin and cisplatin) for four cycles, then with paclitaxel and cisplatin for one cycle. However, the tumor recurred only 4 mo postoperatively, with symptoms of bowel obstruction and uroschesis. She then received transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and γ ray stereotactic radiotherapy. The recurrent mass volume reduced slightly shortly after γ-knife therapy, but soon it continuously enlarged again (Figure 2A). She died of abdominal widespread tumor implantation and metastases (Figure 2B and C) and uncontrolled recurrence 13 mo after initial surgery.

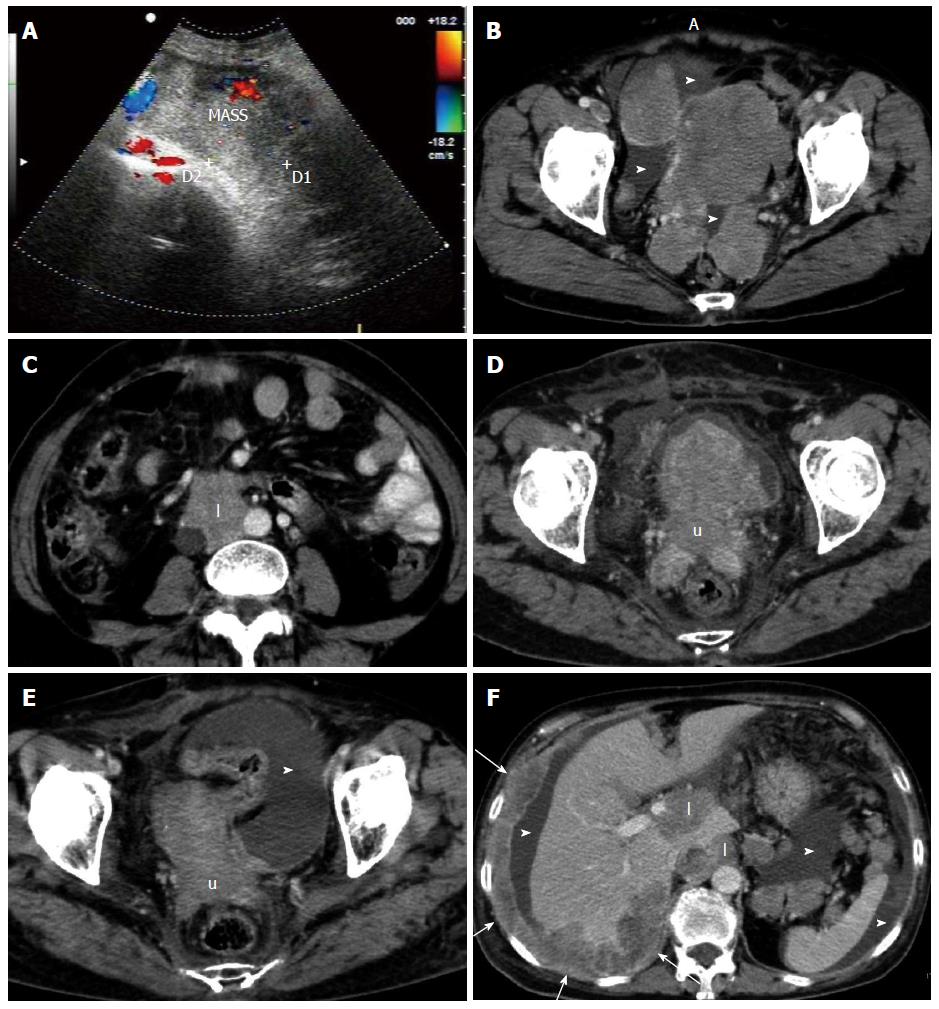

A 64-year-old woman was admitted to hospital with frequent urination and low back pain lasting for 2 wk. On physical examination, a large, medium hardness, poorly defined, non-tender palpable mass was seen predominantly in the mid-right lower abdomen. She also had positive percussion pain in the right kidney area. On US, the tumor was heterogeneous and hypoechoic with surrounding blood flow signals (Figure 3A). CT showed a 114 mm × 175 mm confluent solid mass in the lower abdomen and pelvic cavity with moderate, heterogeneous enhancement, and several other soft-tissue masses in the pelvic cavity (Figure 3B), as well as lymphadenopathy within the retroperitoneum (Figure 3C). The right mid-lower ureter was invaded with moderate hydronephrosis. In addition, mild ascites on the surface of the liver and spleen and in the rectouterine fossa was seen on US and CT. One week later, an incisional biopsy was taken and subjected to histopathological evaluation. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CK, EMA, NSE, CgA, synaptophysin (Syn), CD3 and CD56. Two weeks after exploratory laparotomy, the patient commenced palliative radiotherapy.

For nearly a month, she received a total dose of 54 Gy. Follow-up CT at the later stage of radiotherapy showed that all of the masses were significantly reduced in size (Figure 3D and E). However, extensive peritoneal and hepatic metastatic tumors, as well as lymphatic metastasis appeared shortly thereafter, although the largest mass regressed to 35 mm × 36 mm (Figure 3F). The patient only survived for 4 mo after initial presentation.

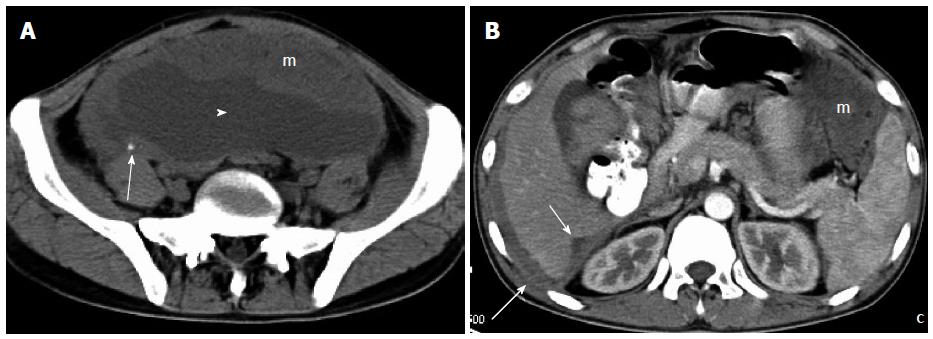

A 24-year-old man presented with a 2-mo history of fatigue and faint abdominal pain and low-grade fever for 2 wk. On physical examination, abdominal distension with shifting dullness was discovered. The patient underwent abdominopelvic CT, which showed diffuse, wavy, omental soft-tissue masses and mesenteric nodules, diffuse peritoneal thickening scalloping the liver edges with liver infiltration, along with massive ascites. The density of the masses was homogeneous on plain scanning, except for punctate calcification, and showed slight to moderate enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT (Figure 4A and B). Laparoscopic exploration was undertaken, and the resultant biopsy revealed a DSRCT. The patient refused further treatment, and died 3 mo after initial presentation.

Abdominopelvic CT findings of all the four patients are summarized in Table 1.

| CT findings | Patients | |

| Initial diagnosis (n = 4) | Follow-up period (n = 3) | |

| Omental/mesenteric/serosal masses | 4 (100) | 3 (100) |

| Pelvic dominant mass | 2 (50) | 3 (100) |

| Tumor calcification | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Liver metastases/infiltration | 1 (25) | 2 (67) |

| Abdominal/pelvic lymphadenopathy | 1 (25) | 3 (100) |

| Ascites | 2 (50) | 2 (67) |

| Urinary tract obstruction | 1 (25) | 2 (67) |

| Bowel obstruction | 1 (25) | 1 (33) |

DSRCT is a small round blue cell tumor similar to other tumors such as Ewing’s sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, and Wilm’s tumor. Typical pathological findings include abundant desmoplastic stroma and poorly differentiated small cells. The tumor is uniquely different from other tumors in that it expresses epithelial, neural, myogenic, and mesenchymal markers. Also, DSRCT generally contains a specific chromosomal abnormality (t11; 21)(p13; q12)[3,7-10]. Most DSRCTs arise in the peritoneal cavity without a primary visceral site of origin, and most investigators believe that the tumor originates from the mesothelium (or from submesothelial or subserosal mesenchyme), which is most extensive in the peritoneum[2,3].

Previous studies have indicated that DSRCT most commonly affects male adolescents and young adults. In our study, distribution by sex did not confirm this male preponderance. The typical age range at diagnosis is 18-25 years[2,11]. In our series, the mean age at diagnosis was 35.5 years (range, 24-64 years), and three (75%) patients were in the third decade of life, and the other was in her 60s. We suppose that the third decade may be a peak period of incidence for DSRCT, and this disease can also occur in older people.

The presenting symptoms of DSRCT are nonspecific, and usually related to the site of involvement. One of our patients complained of frequent urination, and we speculate that tumors compressing the bladder might contribute to this clinical manifestation by sharply reducing bladder capacity.

Patients often initially present with abdominal pain or large, palpable abdominal masses, therefore, CT is most often used for initial diagnosis. Moreover, at the time of initial diagnosis, disseminated tumor with multiple abdominopelvic masses and metastases often exists, and CT is most often used for staging and follow-up[3]. Some studies have reported that the most common anatomical site for this disease is the pelvis, and the second most common site is the peritoneum, with widespread surface masses and nodules[2-7]. Among our cases, three had one or more pelvic masses and two had peritoneal surface masses at the time of initial diagnosis. As the volume of pelvis is far less than the abdomen, pelvic masses always merge into a bulky lobulated mass as they grow, resulting in the presence of a dominant mass in the pelvis for patients with DSRCT. On CT, the hallmark imaging feature is multiple, lobulated, low-attenuation, heterogeneous soft-tissue masses in the omentum or mesentery or along the abdominopelvic peritoneal surfaces, without a distinct organ of origin[3,12-14]. Punctate calcification may be present within tumors in a few cases.

In our cases, solitary peritoneal tumors were found in one patient who did not have any clinical symptoms at initial diagnosis, and with lesions located in the omentum and pararectal region. However, when re-examined 33 mo after surgery, multiple recurrent irregular nodules were seen in the retrovesical space. Thus, we conclude that DSRCT is multicentric in origin, even if it occasionally appears solitary at the time of early detection.

On enhanced CT, large masses always show heterogeneous enhancement after intravenous administration of contrast medium, and the degree of enhancement is mild to moderate. Focal areas of non-enhancement or low attenuation on contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT possibly represent high fibrotic content, in addition to necrosis and intratumoral stale hemorrhage[3,7,12-14]. We found that most smaller masses and peritoneal nodules were almost homogeneous whether on plain or enhanced scanning, such as the first case of ours, the large mass in the mid-abdomen appeared with inhomogeneous cyst, but the small nodule in the pelvis appeared with uniform soft-tissue density.

Apart from multiple peritoneal masses, ascites, lymphadenopathy or liver metastases are often found, and most patients may be asymptomatic for a long period of time and diagnosis is only made when tumor burden is large. Pattern of disease spread includes direct seeding along the peritoneal and serosal surfaces and lymphatic and hematogenous spread[15]. Ascites occurs when the tumor is so extensive that little peritoneal surface remains for absorption of physiological intraperitoneal fluid, and massive ascites implies dismal prognosis. In our cases, ascites, enlarged lymph nodes, and hematogenous dissemination or direct invasion to the liver, as well as hydronephrosis and hydroureter, were also common manifestations at initial or follow-up CT. Hepatic parenchyma is the most common site of extraperitoneal involvement in DSRCT, followed by lung, bone, splenic parenchyma, pleura, and soft tissue[6,15-17]. As for our cases, no metastases to the lungs or other organs, except for the liver, were seen on initial diagnosis or during postoperative follow-up. Urinary tract and bowel obstruction can also be present in the progressive stage secondary to obstruction by tumor.

Ultrasound may be helpful in guiding percutaneous biopsy of relatively superficial lesions but it does not help characterize lesions further, typically demonstrating lobulated, heterogeneous hypo-echoic lesions[18]. 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET-CT) may play an important role in patient management, allowing detection of early recurrence of disease and consequent change in treatment strategy[7,19]. None of our cases had undergone PET-CT examination.

A diagnosis of DSRCT usually can be favored by a combination of factors. The radiologic differential diagnosis for multiple solid peritoneal masses is extensive and includes various neoplastic, inflammatory, and miscellaneous processes. Leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata, a rare condition affecting premenopausal women, can appear similar to desmoplastic small round cell tumor on imaging. Malignant mesothelioma of the peritoneum is usually infiltrative, but may also manifest as discrete tumors, which are usually accompanied by a variable amount of ascites. Rhabdomyosarcoma is most common in younger children, generally < 10 years of age. Desmoid fibromatosis, peritoneal tuberculosis, fibrosing mesenteritis, splenosis, and amyloidosis are other disorders whose infiltrative and/or tumefactive manifestations overlap with the appearance of DSRCT[12,14].

DSRCT is an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis and a mean survival time of 23 mo and an overall 5-year survival rate of 15%[3,20]. Timely diagnosis is therefore critical to the management of these patients. Combination chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and gross total tumor resection or debulking surgery have been advocated to treat patients with DSRCT. Only one of our patients had a relatively good prognosis and survived 42 mo, who had solitary peritoneal tumors discovered incidentally by health examination. The rest who were in advanced stage at initial diagnosis all had extremely poor prognosis and only survived 3-13 mo, even when comprehensive treatment was given. We suggest that early discovery and complete resection, in addition to postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, should be key to good prognosis of DSRCT.

There is no standard chemotherapy regimen for DSRCT. Similar to other small round-cell tumors, DSRCT is alkylator-sensitive and dose-responsive. Kushner et al[21] reported a 100% response rate using a chemotherapy regimen (P6 protocol) consisting of vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and etoposide in 10 patients with DSRCT. Hayes-Jordan et al[6] and Mrabti et al[22] thought anthracycline-based therapy regimens (doxorubicin, etoposide, cisplatin, cyclophosphamide) may be best used for recurrent disease[6,22]. Some patients have been reported to achieve complete radiological remission after chemotherapy [21,23,24]. Goodman et al[24] reported whole abdominopelvic irradiation in 21 patients who had received chemotherapy followed by debulking operation, and the median time to relapse was 19 mo and median overall survival was 32 mo. In one of our cases, pelvic palliative radiotherapy was administered which resulted in a favorable response by shrinking the local tumor, but a large number of new lesions still emerged in the abdomen at the same time. Therefore, whole abdominopelvic irradiation, rather than locoregional radiotherapy, is a more effective treatment strategy for unresectable DSRCT, because the tumor has the property of multicentric growth in the abdominopelvic cavity.

In conclusion, DSRCT is a rare abdominopelvic malignancy with multicentric growth. The third decade may be a peak period of incidence, and the disease can also occur in older people. CT can display characteristic features that are helpful in diagnosis of DSRCT. The presence of a pelvic dominant, lobulated, low-attenuation, heterogeneous soft-tissue mass with mild to moderate enhancement after intravenous contrast medium administration, along with omental, mesenteric, peritoneum or serosal surface masses, is a characteristic feature of DSRCT. Ascites, hepatic metastases, lymphadenopathy, hydronephrosis and hydroureter are also commonly encountered in patients with DSRCT. Prognosis and overall survival rates are generally poor. Early diagnosis and complete resection, in addition to postoperative combination chemotherapy, are important for prognosis of DSRCT. Whole abdominopelvic radiotherapy, rather than locoregional radiotherapy, is more feasible for unresectable DSRCT.

The tumors with multicentric growth arised in the peritoneal cavity without a primary visceral site of origin.

The presenting symptoms of desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) are nonspecific, and usually related to the site of involvement.

The radiologic differential diagnosis for multiple solid peritoneal masses is broad and includes various neoplastic, inflammatory, and miscellaneous processes.

Laboratory examination makes no contribution to diagnosis.

The presence of a pelvic dominant, lobulated, low-attenuation, heterogeneous soft-tissue mass with mild to moderate enhancement after intravenous contrast medium administration, along with omental, mesenteric, peritoneum or serosal surface masses, is a characteristic computed tomography (CT) feature of DSRCT.

Typical pathological findings include abundant desmoplastic stroma and poorly differentiated small cells.

Early diagnosis and complete resection, in addition to postoperative combination chemotherapy, are important for prognosis of DSRCT. Whole abdominopelvic radiotherapy, rather then locoregional radiotherapy, is more feasible for unresectable DSRCT.

Hepatic parenchyma is the most common site of extraperitoneal involvement in DSRCT, followed by lung, bone, splenic parenchyma, pleura, and soft tissue.

No uncommon terms are present in the case report.

These are well described and the CT scans nicely illustrate the tumors.

P- Reviewers: Gaedcke J, Spyropoulos C, Imai K S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Gerald WL, Rosai J. Case 2. Desmoplastic small cell tumor with divergent differentiation. Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gerald WL, Miller HK, Battifora H, Miettinen M, Silva EG, Rosai J. Intra-abdominal desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. Report of 19 cases of a distinctive type of high-grade polyphenotypic malignancy affecting young individuals. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:499-513. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Bellah R, Suzuki-Bordalo L, Brecher E, Ginsberg JP, Maris J, Pawel BR. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor in the abdomen and pelvis: report of CT findings in 11 affected children and young adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1910-1914. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Kusumoto M, Oyama T, Ishikawa H, Moriyama N. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: imaging findings associated with clinicopathologic features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:579-583. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kis B, O’Regan KN, Agoston A, Javery O, Jagannathan J, Ramaiya NH. Imaging of desmoplastic small round cell tumour in adults. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hayes-Jordan A, Anderson PM. The diagnosis and management of desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a review. Curr Opin Oncol. 2011;23:385-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang WD, Li CX, Liu QY, Hu YY, Cao Y, Huang JH. CT, MRI, and FDG-PET/CT imaging findings of abdominopelvic desmoplastic small round cell tumors: correlation with histopathologic findings. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:269-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ordóñez NG, Zirkin R, Bloom RE. Malignant small-cell epithelial tumor of the peritoneum coexpressing mesenchymal-type intermediate filaments. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:413-421. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Layfield LJ, Lenarsky C. Desmoplastic small cell tumors of the peritoneum coexpressing mesenchymal and epithelial markers. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:536-543. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Norton J, Monaghan P, Carter RL. Intra-abdominal desmoplastic small cell tumour with divergent differentiation. Histopathology. 1991;19:560-562. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lae ME, Roche PC, Jin L, Lloyd RV, Nascimento AG. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of 32 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:823-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pickhardt PJ, Fisher AJ, Balfe DM, Dehner LP, Huettner PC. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the abdomen: radiologic-histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1999;210:633-638. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kim YS, Cha SJ, Choi YS, Kim BG, Park SJ, Chang IT. Retroperitoneal desmoplastic small round cell tumor: pediatric patient treated with multimodal therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4212-4214. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Iyer RS, Schaunaman G, Pruthi S, Finn LS. Imaging of pediatric desmoplastic small-round-cell tumor with pathologic correlation. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2013;42:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arora VC, Price AP, Fleming S, Sohn MJ, Magnan H, LaQuaglia MP, Abramson S. Characteristic imaging features of desmoplastic small round cell tumour. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baltogiannis N, Mavridis G, Keramidas D. Intraabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumour: report of two cases in paediatric patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2002;12:333-336. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sharma S, Vikram NK, Thulkar S, Goel S. Case of the season. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor. Semin Roentgenol. 2001;36:3-5. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Thomas R, Rajeswaran G, Thway K, Benson C, Shahabuddin K, Moskovic E. Desmoplastic small round cell tumour: the radiological, pathological and clinical features. Insights Imaging. 2013;4:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ben-Sellem D, Liu KL, Cimarelli S, Constantinesco A, Imperiale A. Desmoplastic small round cell tumor: impact of F-FDG PET induced treatment strategy in a patient with long-term outcome. Rare Tumors. 2009;1:e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lal DR, Su WT, Wolden SL, Loh KC, Modak S, La Quaglia MP. Results of multimodal treatment for desmoplastic small round cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:251-255. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kushner BH, LaQuaglia MP, Wollner N, Meyers PA, Lindsley KL, Ghavimi F, Merchant TE, Boulad F, Cheung NK, Bonilla MA. Desmoplastic small round-cell tumor: prolonged progression-free survival with aggressive multimodality therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1526-1531. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Mrabti H, Kaikani W, Ahbeddou N, Abahssain H, El Khannoussi B, Amrani M, Errihani H. Metastatic desmoplastic small round cell tumor controlled by an anthracycline-based regimen: review of the role of chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Farhat F, Culine S, Lhommé C, Duvillard P, Soulié P, Michel G, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Théodore C, Schreinerova M, Droz JP. Desmoplastic small round cell tumors: results of a four-drug chemotherapy regimen in five adult patients. Cancer. 1996;77:1363-1366. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Goodman KA, Wolden SL, La Quaglia MP, Kushner BH. Whole abdominopelvic radiotherapy for desmoplastic small round-cell tumor. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |