INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection (CDI) represents an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), resulting in longer hospital stays and higher healthcare expenses[1,2]. CDI has been reported to occur in 0.9%-2.2% of admissions for Crohn’s disease and 1.8%-5.7% for ulcerative colitis (UC); these incidence rates are higher than in the general population (0.48%)[1,3] and have shown an increasing trend in recent years[2]. It has also been reported that 8.2% of UC patients and 1% of those with Crohn’s disease are silent carriers, without distinct episodes of CDI[4]. The major risk factors for CDI in IBD are drug-related, including the use of antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, clindamycin, cephalosporins, and penicillins[2,4,5], as well as proton pump inhibitors or immunosuppressive therapies[6]. Baseline or newly initiated therapies with corticoids triple the risk of CDI and double the mortality rate, in a dose- and duration-independent manner[7,8]; furthermore, immunomodulators, such as azathioprine, methotrexate and 6-mercaptopurine, increase the risk of CDI, especially in UC patients[2,4]. Other CDI risk factors are host-related, such as a patient age over 65 years, prolonged hospital stay, and history of gastrointestinal surgery[4].

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old male patient with a history of UC in the last 2 years, with frequent flare-ups (more than six per years) treated with steroids and mesalamine, was admitted to our hospital. One month before admission, the patient had experienced a new relapse with rectal bleeding, diarrhea (9-10 stools/d) and fever (38 °C), which was treated with mesalamine and steroids accompanied by ciprofloxacin to address a concomitant urinary infection. Despite the therapy, the status worsened, with the patient experiencing fever of 38.4 °C, 20 stools/d, and abdominal distension without tenderness. A colonoscopy performed in a different hospital revealed the presence of pseudomembranes, supporting the diagnosis of CDI superimposed on UC. Metronidazole and vancomycin were administrated for 5 d.

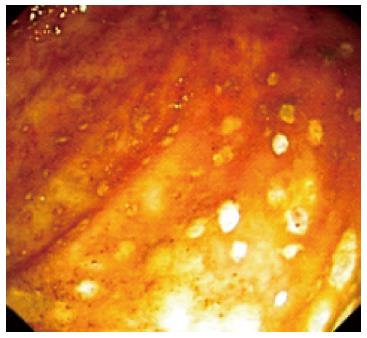

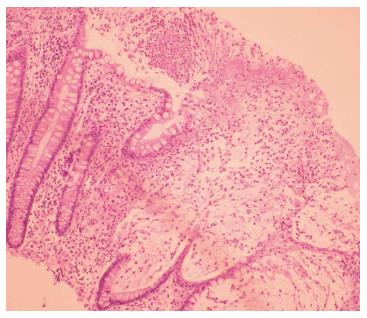

On admission to our hospital, the patient had more than 20 stools/d, fever, and leukocytosis (24000/mm3), with 87% neutrophilia, normal C-reactive protein (CRP) level, no anemia, hypoproteinemia (5 g/dL), and hypoalbuminemia (2.6 g/dL). A stool culture, including C. difficile toxins, was negative. The presence of pseudomembranes with a diminished vascular pattern of the mucosa from the cecum to the sigmoid colon was noted on a repeat colonoscopy; however, the rectum appeared normal (Figure 1). Colonic biopsy showed leukocytes, fibrin, mucus, and epithelial cells adherent to the surface of the underlying inflamed and necrotic mucosa, supporting the diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis (Figure 2). X-ray radiography revealed no distension of the transverse or right colon, but the transabdominal ultrasound showed the presence of ascites. With respect to the potential diagnosis of relapsing CDI, the patient was started on oral vancomycin (125 mg qid, continued for 14 d); three days later, azathioprine and a higher dose of steroids was administered, which resulted in clinical improvement. Within 15 d of discharge, the patient reported a relapse with 8 stools/d, at which time he self-administered oral metronidazole for 10 d without consulting the doctor, but which provided a favorable outcome.

Figure 1 Pseudomembranous colitis in the ulcerative colitis patient.

Colonoscopy image showing pseudomembranes in the descending colon, with a loss mucosal vascular pattern.

Figure 2 Colonic histology of Clostridium difficile infection superimposed on ulcerative colitis.

Necrosis of superficial crypts with a dense infiltrate of neutrophils, fibrin, and cellular debris covering the mucosal surface.

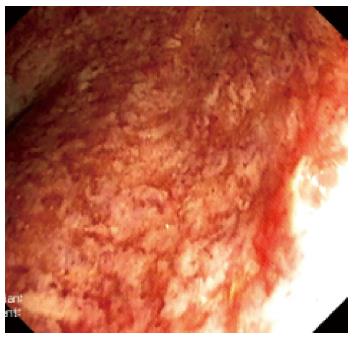

Three months after the initial admission to our hospital, the patient presented again with 6 stools/d, bleeding, and urgency. His temperature was normal, CRP level was slightly elevated, and C. difficile toxins were again negative. Proctosigmoidoscopy revealed multiple ulcerations, friability, mucosal edema, and loss of vascular pattern. Histopathologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry indicated severe UC and no cytomegalovirus (CMV)-induced cytopathic damage (“inclusion bodies”). After an infliximab (5 mg/kg per day) induction regimen at 0, 2 and 6 wk, the patient was still experiencing 6 stools/d, showed signs of severe colitis in endoscopy (Figure 3), and had a two-fold increase in CRP level. The trough level of infliximab measured at 8 wk after initiation was 0.062 μg/mL, and the anti-infliximab antibodies were negative (ELISA kit, Immundiagnostik, Bensheim, Germany). The low trough level suggested a partial response, and the dose of infliximab was consequently increased to 10 mg/kg per day; the patient showed a rapid clinical remission after the first administration, as evidenced by 1 stool/d, without blood. Remission was confirmed endoscopically after the administration of the second 10 mg/kg per day dose, and the patient was returned to 5 mg/kg per day, with a detectable trough infliximab level of 3 μg/mL. After a 12-mo follow-up, the patient remained in steroid-free remission.

Figure 3 Severe endoscopic aspect of ulcerative colitis.

Ulcerations, loss of vascular pattern and edema of the mucosae were noted in the rectum.

DISCUSSION

C. difficile is a gram-positive, spore-forming anaerobic bacterium that is revealed when the normal colonic flora is disrupted[9]. The bacteria produce enterotoxin A and cytotoxin B, which bind to specific receptors in colonic mucosal cells and gain entry to the intracellular space, leading to a systemic inflammatory response (fever, multi-organ failure), toxic megacolon, and perforation. The capability of bacterial adherence to the mucosa is genetically determined, influenced by polymorphisms of the host TNFRSF14 gene[10]. Colonic infection is common[2], but small intestinal involvement or pouchitis have been reported with CDI[11,12]. Although IBD patients with CDI acquire their infection in an outpatient setting in 47%-79% of cases[2,4,13], the number of in-hospital infections is increasing.

The clinical manifestations of CDI-associated IBD are usually indistinguishable from those of IBD alone, such as watery diarrhea or bloody stools, with systemic signs of severity (fever, tachycardia, hypotension), abdominal distention, or signs of complications (fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, or bowel perforation)[6]. Leukocytosis sometimes occurs, even before diarrhea[14], indicating the need to test for CDI[11], as high numbers of leukocytes and increased serum levels of creatinine are associated with the development of severe-complicated CDI[15]. Hypoalbuminemia is related to severe diarrhea as a result of protein-losing enteropathy and negative acute-phase proteins[16], which may explain the ascites in our patient. Though not observed in the present case, ascites associated with the distention of the transverse colon can also suggest toxic megacolon and bowel perforation. The diagnosis of CDI is based on toxin detection in stool samples, with low sensitivity, or on colonic histology, which has only been reported as positive in 5% of CDI-IBD patients[6]. Pseudomembranes containing mucus, protein, and inflammatory cells are usually detected on colonoscopy in isolated CDI, but they may be absent if the patient is taking immunomodulators[2,17], though their presence does not influence the clinical outcome[18].

The long-term outcome of the patient in the present case was very good after only two high doses of infliximab, with complete remission one year later. This is in agreement with several other reported CDI-UC cases treated with infliximab[19]. It has been postulated that infliximab therapy may even protect against CDI[10]. The initiation of infliximab therapy is not associated with CDI[7], based on a pooled analysis of three UC studies and seven Crohn’s disease studies[20]. One study reported that despite similar short-term outcomes for CDI-IBD and IBD patients in terms of cyclosporine use and length of hospitalization, the patients with CDI-IBD may have worse long-term outcomes[21], with 37%-50% requiring hospitalization for treatment of flare-ups[2,22]. Furthermore, intensification of treatment for IBD occurs more often after CDI[22,23], either by initiation or escalation of biologic therapy or immunosuppressants[24]. However, the escalation of IBD treatment should be avoided in the first 72 h after starting CDI therapy[16], as demonstrated in the present case. The mortality in CDI-IBD patients is 3.2-6 times greater than in patients with IBD alone[6,18,25,26], with a mortality rate as high as 25%[5]. It has been reported that 10%-35% of CDI patients ultimately require a colectomy[2,4,18,21,22,24]. Patients with CDI-IBD should be followed up carefully and their IBD aggressively managed.

CDI recurs in about 11%-30% of patients after the initial course of treatment[6,14,27] by reinfection with the initial strain or with a new strain, which usually occurs 1-3 wk after antibiotic discontinuation. Treatment with metronidazole is not recommended beyond the first recurrence due to concerns for peripheral neuropathy following extended use, especially in the elderly. Moreover, oral administration of metronidazole has a poor treatment outcome, with a reported failure rate of up to 50%[28]. As a result, the direct use of oral vancomycin has been recommended as an initial therapy for CDI-IBD[2], with prolonged, tapered and pulsed-dose vancomycin as the preferred approach for multiple recurrences of CDI[29]. Alternative treatments for recurrence include fecal microbiota transplantation, which has shown a high rate of success[30]. 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) therapy is considered a protective option for patients with CDI-IBD[4]; although, the prescribed mesalamine was ineffective in the current case. Combination treatment with antibiotics and immunosuppressants has been associated with colectomy or death in 12% of cases at the 3-mo follow-up[6], though this was not confirmed in other small studies[13]. Newer antibiotics, probiotics, and immunotherapy may be beneficial, but more investigation is needed[16].

In the case reported here, CDI worsened the short-term outcome of UC, most probably because C. difficile alters the natural history of UC by activating an innate immune response to the organism that activates the UC[19]. This case highlights the clinical challenges that can be encountered during UC therapy, with the potential benefit of escalating infliximab dosage to a high level in order to resolve a recurrent CDI. This approach led to a good long-term (12-mo) outcome, but no guidelines for the use of infliximab trough level to guide modification of therapy are yet available for such situations. It is important to note that our patient had a prolonged hospital stay and previous ciprofloxacin and corticosteroid therapy, which represent risk factors for CDI.

The decision for the escalation of infliximab in this case rather than a colectomy after the induction period was based on clinical findings and the trough level of infliximab. A level below 0.5 μg/mL indicates the need for dose escalation or a shortening of the interval between infusions[31]. Detectable trough serum infliximab after an induction period predicts clinical remission, endoscopic improvement, and a lower risk for colectomy in UC patients[32], which corresponds to the improved long-term outcome in our patient. However, a recent study has shown that a low level of infliximab (< 2.2 μg/mL) at week 14 leads to the formation of anti-infliximab antibodies and infliximab discontinuation[33]. However, in a retrospective study of IBD patients who were no longer responding to infliximab, the clinical improvement upon intensification of infliximab therapy occurred irrespective of infliximab serum trough levels or antibodies[34]. Though not detected in our patient, particular attention must be paid to concomitant CMV infection, which can be diagnosed by hematoxylin and eosin staining for evidence of cytopathic damage in epithelial cells, or by immunohistochemistry, PCR DNA detection, or serum IgM detection[35].

In conclusion, this case highlights some of the difficulties in treating CDI-UC. The short-term outcome of the patient was worsened by CDI, possibly resulting from C. difficile activation of an innate immune response that stimulated the UC[21]. As demonstrated here, low trough levels of infliximab prompted the administration of a higher dose with a favorable treatment result, however no guidelines for the use of trough levels are yet available for such situations. Thus, trough levels of infliximab may be useful and safe for guiding the treatment of UC worsened by CDI.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 37-year-old male patient with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) diagnosis 2 years prior and subsequent treatment with steroids and mesalamine but with frequent flare-ups over that period, was admitted for a current flare-up with symptoms of diarrhea, fever, rectal bleeding, abdominal distention but no tenderness.

Clinical diagnosis

Severe flare-up of UC.

Differential diagnosis

Severe flare-up of UC with or without associated cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, tuberculosis or Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) infection (CDI).

Laboratory diagnosis

Leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, negative stool toxins for C. difficile.

Imaging diagnosis

The initial colonoscopy performed showed pseudomembranes with diminished vascular pattern. A second colonoscopy showed multiple ulcerations, friability, mucosal edema, loss of vascular pattern with histopathological appearance suggesting severe UC.

Pathological diagnosis

The initial pathological examination showed leukocytes, fibrin, mucus, and epithelial cells adherent to the surface of the underlying inflamed and necrotic mucosa, which sustained the diagnosis of pseudomembranous colitis on UC. The second examination using hematoxylin-eosin staining and immunohistochemistry showed no CMV-induced cytopathic damage (“inclusion bodies”).

Treatment

For severe flare-up of UC after recurrent CDI, an infliximab induction regimen (5 mg/kg per day) was administered at weeks 0, 2 and 6. After a low trough level of infliximab was detected at week 8, a high-dose infliximab regimen (10 mg/kg per day) was given at weeks 14-22. When the trough level increased, the dose was reduced to 5 mg/kg per day and the patient was found to be in clinical remission at the 1-year follow-up appointment.

Term explanation

Detectable but low trough level of infliximab represents an indication for increasing the dose or shortening the interval. The optimal trough level has not yet been established.

Experiences and lessons

Trough level of infliximab is a useful tool in guiding treatment of UC worsening associated with CDI.

Peer review

Infliximab therapy was safe in the patient with worsened UC associated with recurrent CDI. Measurement of the trough level of infliximab was helpful in guiding an increase in infliximab therapy. The presence of ascites, in this case, was a sign of hypoalbuminemia correlated with severe diarrhea as a result of protein-losing enteropathy; however, ascites associated with distention of the transverse colon can sugest toxic megacolon and bowel perforation, which was not the case for this particular patient.