Published online May 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5008

Revised: September 12, 2013

Accepted: September 16, 2013

Published online: May 7, 2014

Processing time: 376 Days and 16.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the association between mutations in oligomerisation domain 2/caspase recruitment domains 15 (NOD2/CARD15) and the natural history of Crohn’s disease (CD) to identify patients who would benefit from early aggressive medical intervention.

METHODS: We recruited thirty consecutive unrelated CD patients with a history of ileo-caecal or small bowel resection during the period 1980-2000; Fifteen patients of these had post-operative relapse that required further surgery and fifteen did not. Full sequencing of the NOD2/CARD15 gene using dHPLC for exons 3, 5, 7, 10 and 12 and direct sequencing for exons 2, 4, 6, 8, 9 and 11 was conducted. CD patients categorized as carrying variants were anyone with at least 1 variant of the NOD2/CARD15 gene.

RESULTS: About 13.3% of the cohort (four patients) carried at least one mutant allele of 3020insC of the NOD2/CARD15 gene. There were 20 males and 10 females with a mean age of 43.3 years (range 25-69 years). The mean follow up was 199.6 mo and a median of 189.5 mo. Sixteen sequence variations within the NOD2/CARD15 gene were identified, with 9 of them occurring with an allele frequency of greater than 10 %. In this study, there was a trend to suggest that patients with the 3020insC mutation have a higher frequency of operations compared to those without the mutation. Patients with the 3020insC mutation had a significantly shorter time between the diagnosis of CD and initial surgery. This study included Australian patients of ethnically heterogenous background unlike previous studies conducted in different countries.

CONCLUSION: These findings suggest that patients carrying NOD2/CARD15 mutations follow a rapid and more aggressive form of Crohn’s disease showing a trend for multiple surgical interventions and significantly shorter time to early surgery.

Core tip: This study conducted a full gene sequencing of nNucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain 2/caspase recruitment domains 15 (NOD2/CARD15) within an Australian cohort of patient with Crohn’s disease (CD). In this study, there was a trend to suggest that patients with the 3020insC mutation have a higher frequency of operations compared to those without the mutation. Patients with the 3020insC mutation had a significantly shorter time between the diagnosis of CD and initial surgery. The clinical significance of understanding pathogenic NOD2/CARD15 mutations is to shift management to a top down approach whereby active medical therapy could be introduced at an early stage to impact on aggressive disease behaviour in mutation positive patients.

-

Citation: Bhullar M, Macrae F, Brown G, Smith M, Sharpe K. Prediction of Crohn’s disease aggression through

NOD2 /CARD15 gene sequencing in an Australian cohort. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(17): 5008-5016 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i17/5008.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5008

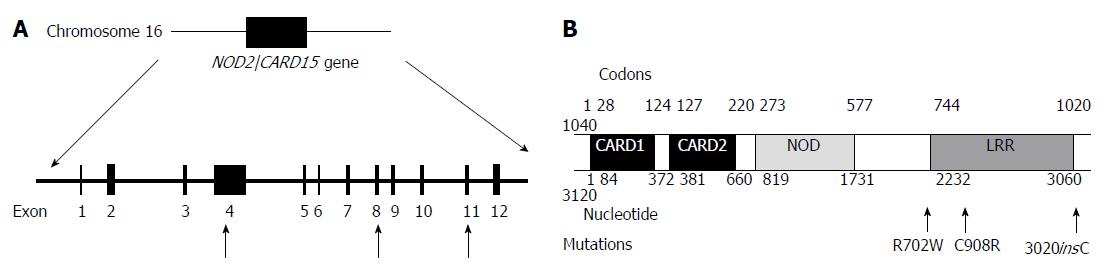

The pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is complex and is thought to result from the interaction of environmental factors with genetic predisposition[1]. Familial aggregation of the disease and studies of twins have strongly suggested that genetic factors contribute to IBD, especially Crohn’s disease[2] - a hypothesis that was substantiated with the discovery of a susceptibility locus in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 16 called IBD1[3]. Subsequently, two independent research groups reported that the nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain 2/caspase recruitment domains 15 (NOD2/CARD15) gene located on chromosome 16 within the IBD-1 region is associated with increased susceptibility to CD[1,4] . This association was later confirmed by other research groups[5-13].

Approximately 30% of Crohn’s patients carry one copy of a mutated NOD2/CARD15 allele and about 17% of Crohn’s patients carry two mutated NOD2/CARD15 alleles[14], conferring a 2 to 4 fold and 20-40 fold increased risk of developing CD respectively.

Studies have demonstrated three mutations or sequence variants which exhibit the strongest association with the development of CD[7]. These are “3020insC” on exon 11, which is a frameshift mutation[15], and the missense mutations located on exons 4 and 8; these lead to the amino acid substitutions Arg702Trp and Gly908Arg respectively. However, whilst it has been noted for 9 years that these mutations are associated with Crohn’s disease, the consequences of these mutations on their protein function is yet unknown.

The only consistent finding to date regarding the clinical impact of NOD2/CARD15 variants concerns disease localization[6,8,10,16-21]. Some studies have also reported an association between NOD2/CARD15 mutations and fibrostenotic behaviour[6,11,22], whilst others have reported a higher incidence of fistulas in NOD2/CARD15 variant patients[11,19,22,23]. The reasons for these observations are unknown but are important for further investigation as it will help in understanding the pathophysiology of NOD2/CARD15 mutations.

Several lines of evidence are compatible with a significant role of NOD2/CARD15 variants in determining an association with earlier age of disease onset[6,7,20]. This is consistent with genetic evidence that a younger age of diagnosis identifies families with greater linkage to the IBD1 locus[24].

Currently, little is known about the association between NOD2/CARD15 mutations and the requirement for initial surgery and for surgical recurrences in CD. Studies conducted to evaluate the direct association of NOD2/CARD15 mutations with surgical requirements have reported variable findings but generally there is support for prediction of subsequent requirements for surgery. Most of the published data have shown an increased association between NOD2/CARD15 mutations with ileal surgery, and the mutation with the strongest association was found to be the 3020insC mutation[5,19,25-28]. In three independent studies, one carried out in Germany[20], another in Spain[21] another in Italy[29], patients with mutations of the gene presented an increased risk of repeated surgery, and such surgery was required earlier. These findings were even reinforced within the pediatric population whereby 2 studies have demonstrated that NOD2/CARD15 mutations were a predictor of earlier age of surgery within a pediatric population[30,31].

Perhaps the greatest shortcoming, though, is that all associations between NOD2/CARD15 mutations and the requirement of surgery have been based only on the analysis of the three most common mutations within the gene. One of the research studies only evaluated the most common insertion mutation. None of these studies have fully sequenced the NOD2/CARD15 gene. The current study was designed with the intention of fully sequencing the NOD2/CARD15 gene in all recruited patients to establish the frequency of variant alleles and unravel other mutations in the aforementioned gene. With that, this research aimed to determine if NOD2/CARD15 mutations in CD patients are able to predict disease progression including the need for early surgery as well as post-operative relapse requiring re-operation, with a view to predict those who may need early interventions to prevent a relapse from occurring. Full sequencing in itself will provide unique information with regard to the distribution spectrum of NOD2/CARD15 mutations within the ethnically heterogeneous Australian population.

The study was approved by the Human Resource Ethics Committee at The Royal Melbourne Hospital and followed consent and privacy procedures.

Thirty unrelated Crohn’s disease patients were ascertained consecutively through a search of The Royal Melbourne medical records and private records of RMH consultants, filtering on patients with a history of ileo-caecal or small bowel resections during the time period of 1980-2000. The diagnosis of CD was based on standard clinical, radiological and histological criteria.

The patients were divided into two main groups: (1) Fifteen patients who had post-operative relapse that required surgical interventions; and (2) Fifteen patients who did not have post-operative relapse that required surgical interventions, composing the control group.

We defined surgery as an active procedural intervention including bowel resection, stricturoplasty and balloon dilatation of strictures. We included patients only with a history of ileo-caecal or small bowel resections as their initial type of surgery, as NOD2/CARD15 mutations have been associated with this group of patients, and we wanted to enrich our genotyped population with mutation carriers.

Although the recruited patients underwent initial small bowel or ileo-caecal resection(s), we did not exclude patients with disease involvement in other parts of the digestive tract. The location of disease was recorded from information obtained in radiological, endoscopic and histological examination, and updated in association with later consultations.

Indication for the requirement of surgical interventions (initial or subsequent surgeries) was based according to clinical judgement of the caring consultant and/or surgeon according to clinical presentation, pre-operative diagnostic findings and intra-operative findings without access to genotyping of NOD2/CARD15. Inconsistency in surgical decision making was minimized because the overwhelming majority of surgical procedures were done by the same integrated surgical team.

The indications for surgical interventions composed 5 main groups: (1) failed medical treatment; (2) symptomatic stricturing disease if persistent intestinal obstruction was found on radiological, endoscopic, clinical or intra-operative findings; (3) perforating disease if complicated enterocutaneous fistulae, intra-abdominal fistulae or acute free perforations were present; (4) the presence of intra-abdominal abscesses; and (5) others, including cancer, haemorrhage, toxic dilation.

Group 2 patients were selected from patients who had one or more subsequent surgeries following the initial resection for the recurrence of CD, with the requirement for surgery being consistent with the indications described above. Surgical procedures as a result of complications of the previous surgery, incomplete/abandoned surgery, ileostomy, colostomy and CD-unrelated surgery were not included in interventions analysed in the series. The number of subsequent surgeries undertaken and the time between the surgeries were recorded.

Disease behaviour was based on the Vienna classification: (1) perforating for enterocutaneous/intra-abdominal fistulae, abscesses and inflammatory masses; (2) stricturing for narrowing of the intestinal lumen from fibrostenotic lesions; and (3) inflammatory for the rest of CD patients. The Crohn’s disease activity index was noted if present in the medical records.

Family history is of significance if one first or second degree relative has CD. Smoking habit refers to smoking behaviour in July 2005 as reported by the patient, with patients being divided into 3 groups: current smokers, non-smokers (patients who never smoked) and ex-smokers (patients who had given up smoking at least 1 year prior). Extra-intestinal manifestations were defined as follows: Type 1 peripheral arthralgia/arthritis,primary sclerosing cholangitis, affections of the skin (pyoderma gangrenosum) or eye (iritis, uveitis, etc.).

The medical history of the patient was collected through retrospective review of medical records and updated during later consultations and/or by phone. The clinical and demographical data were collected in concordance to an established regional database. The demographic data included age, gender, race, smoking habits, family history of IBD and dietary history. The clinical data included disease phenotype, age of onset, age at initial and subsequent surgical interventions, date and type of surgery, location of disease, disease phenotype, extra-intestinal manifestations, and intra and post-operative complications.

A sample of blood was collected from all patients for the full sequencing of the NOD2/CARD15 gene using dHPLC for exons 3, 5, 7, 10 and 12 and direct sequencing for exons 2, 4, 6, 8, 9 and 11. The investigators who determined the genotypes were blinded to the clinical characteristics of the patients. CD patients categorized as carrying variants were anyone with at least 1 variant of the NOD2/CARD15 gene.

Analysis was carried out using Minitab or R statistics package. Categorical variables were compared using Fishers exact test. Continuous variables were analysed using Student t test (and some non-parametric equivalents, namely the Mann-Whitney test). The Mann-Whitney test was often used as the distribution of data was often skewed and this test is a distribution-free test. All P values were two sided, and a value of less than 0.05 was considered to be a statistically significant difference.

This cohort of 30 patients were CD patients with a history of ileo-caecal or small bowel resection during the time period of 1980-2000. Group 1 consisted of 15 patients who had post-operative relapses requiring further surgery and Group 2 consisted of 15 patients who did not require further surgery. There were 20 males and 10 females with a mean age of 43.3 years (range 25-69 years). All patients were followed up until December 2005, with a mean follow up of 199.6 mo and a median of 189.5 mo. Nine patients (30%) were current smokers, 3 (10%) were ex-smokers and 18 (70%) were non-smokers. There was no evidence of an association between smoking behaviour and disease progression. None of the patients reported a family history of CD in a first or second degree relative.

In total, 16 sequence variations within the NOD2/CARD15 gene were identified, with 9 of them occurring with an allele frequency of greater than 10 %. The sequence variations are S178S nt534C>G (Exon 2), IVS2-25G>T (Exon 2), P268S nt 802C>T (Exon 4), R702W nt 2104C>T (Exon 4), R459R nt 1377C>T (Exon4), R587R nt 1761 T>G (Exon 4), L248R nt 743T>G (Exon 4), R703C nt 2107C>T (Exon 4), T294T nt882 T>A (Exon 4), A611A nt 1833 C>T (Exon 4), IVS4+10 A>C (Exon 4), IVS5+27G>A (Exon 5), IVS4-43C>T (Exon 5), G908R nt 2722G>C (Exon 8), V955l nt 2863G>A (Exon 9), 3020insC (Exon 11). Of these mutations, IVS2-25G G>T on Exon 2 has not been previously reported.

In total, 8 patients (26.6% of the CD patients) carried at least one known pathogenic mutation within the NOD2/CARD15 gene located on chromosome 16 (Figure 1). The allele frequencies for the pathogenic mutations R702 W (Exon4), G908R (Exon 8) and 3020insC (Exon 11) were 16.7%, 3% and 13.3%. One of the patients was a simple homozygote, 2 patients were compound heterozygotes (R702W and 3020insC) and (G908R and 3020insC) and the remainder 5 patients were simple heterozygotes.

There were 12 patients with the P268S sequence variation. Nine of these patients were heterozygous for the P268S variation and 3 were homozygous. All 8 patients with the pathogenic mutations possessed the P268S variant and both the patients who were compound heterozygotes for the pathogenic mutations were also homozygous for the P268S variation. The P268S change was not found to independently reduce the time between surgery and diagnosis (P = 0.067).

Patients with any pathogenic mutation showed a trend to a higher frequency of operations. According to the Mann-Whitney test performed, we found that patients without any pathogenic mutation had a median of 0.79 surgical interventions per 100 mo whilst those with any pathogenic mutation had 1.09 surgical interventions per 100 mo. However, this was not statistically substantiated (P = 0.096). Among the remainder of the mutation negative patients, 12 patients had 1 surgical intervention, 5 patients had 2 surgical interventions, 3 patients had 3 surgical interventions and only 1 patient had 4 and 5 surgical interventions (Table 1). As all the patients had different lengths of follow-up time, we assessed the number of operations per 100 mo in relation to the NOD2/CARD15 mutation to investigate whether the mutation predicted patients at a higher risk of operation than those without.

| Surgical interventions | Pathogenic mutation positive (n = 8) | Pathogenic mutation negative (n = 22) |

| 1 | 2 | 12 |

| 2 | 1 | 5 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 |

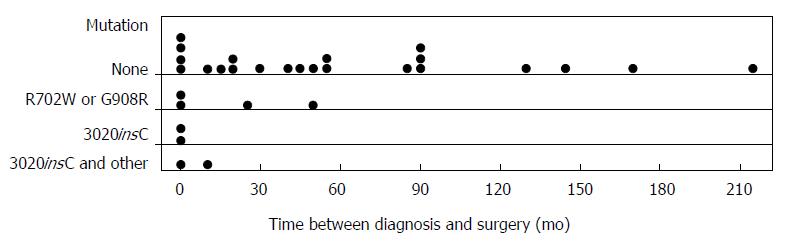

Patients with any pathogenic mutation had a significantly reduced time between their diagnosis of CD and initial surgery. The effect was even more pronounced with the 3020insC mutation, with 3 out of 4 mutation positive patients requiring their first resection almost immediately after CD diagnosis. The mean time between age at diagnosis and 1st surgical resection for patients with any pathogenic mutation was 0.5 mo compared to a median time of 48.5 mo for patients who were negative for a NOD2/CARD15 pathogenic mutation (P = 0.027). The mean time between time of diagnosis and surgery for patients with a 3020insC mutation was 2.25 mo, with a median of 0.5 mo whereas for patients with R702W or G908R mutation, the median was 12 mo. The distribution of the patients, both positive and negative for the 3020insC mutation was skewed (Figure 2), as expected.

We analysed the phenotypic characteristics presented by all 30 CD patients to determine if a positive 3020insC mutation is associated with clinical variables that could serve as predictors of patients at high risk of disease relapse and re-operation. These clinical phenotypes include disease behaviour, location of disease, number of diseased locations and extra-intestinal manifestations of CD (Table 2). The data on clinical features were recorded from time of diagnosis to December 2005. In our series, there was no significant association between a positive pathogenic mutation and any of the aforementioned clinical features with a P < 0.05. Also, biallelic carriers did not have more aggressive behaviour than mono allelic carriers.

| Characteristics | 3020insC mutation positive (n = 4) | 3020insC mutation negative (n = 26) |

| Disease behaviour | ||

| Perforating | 1 | 5 |

| Stricturing | 4 | 14 |

| Inflammatory | 3 | 7 |

| Location of CD lesions | ||

| Small bowel | 4 | 7 |

| Ileocaecal | 6 | 19 |

| Colonic | 1 | 7 |

| Anorectal | 1 | 1 |

| Others | 0 | 0 |

| No of locations involved | ||

| 1 | 4 | 13 |

| 2 | 4 | 7 |

| 3 | 0 | 2 |

| 4+ | 0 | 0 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | 0 | 3 |

Interestingly, though not statistically significant, all eight gene positive patients had stricturing disease behaviour. None of the 3020insC mutation positive patients had extra-intestinal manifestations. Three patients without the mutation displayed extra-intestinal manifestations. These were arthritis, marginal keratitis and Sweets syndrome.

In this study, it was found that a NOD2/CARD15 mutation predicted initial disease aggressiveness in CD with mutation positive patients having a significantly reduced time between the diagnosis of CD and initial surgery. There was also a trend to suggest that patients with the pathogenic mutations have a higher frequency of operations compared to those without the mutation. These findings were particularly significant in the presence of the 3020insC mutation. If confirmatory studies establish these relationships, active medical therapy could be introduced at an early stage to impact on aggressive disease behaviour.

There was a statistically significant association between the pathogenic NOD2/CARD15 mutations and the requirement for early surgical intervention. Patients with the mutation had a significantly reduced time between their diagnosis and 1st surgical resection. This association was found to be more significant in patients with the 3020insC mutation. In fact, 3 out of 4 patients with the 3020insC mutation required their first surgical resection immediately after diagnosis. This data would suggest that that the mutation leads to a more aggressive form of disease, which rapidly progresses requiring early surgical intervention. NOD2/CARD15 mutations seem to act by either impairing the regulatory immune response (allowing patients to be vulnerable to infections that set off CD at an earlier age) or initiating an enhancement of the effector limb of the immune response to bacterial invasion (acting as an initiating factor in early onset CD). In the same way, the mutation could cause a more rapid and aggressive clinical course of disease because either an impaired immune response is unable to adequately contain the bacterial invasion or the mutation itself is fuelling the excessive inflammatory response. The 3020insC mutation is a frameshift mutation resulting in the truncation of the protein in the leucine rich repeat region, which is the main region implicated in the immune regulation pathway, which may explain why the 3020insC mutation leads to an even more aggressive progression of disease compared to the other 2 pathogenic mutations.

We then assessed the association between gene status and the pattern of disease, as previous studies have reported that NOD2/CARD15 mutations are associated with fibrostenosing disease. Our current results are inconclusive to date in analysing the relationship between NOD2/CARD15 mutations and the behaviour of the disease. Interestingly, however, all mutation positive patients have a stricturing disease behaviour, either alone or in combination with a perforating and/or inflammatory pattern, irrespective of the nature of the indication for their initial surgery. This means that our finding is consistent with previously reported data, though it has not been statistically substantiated possible due to the small sample size.

Following the clinical observation that one third of patients need re-operation after initial surgery[21], we questioned whether the NOD2/CARD15 mutation was responsible for post operative relapses requiring further surgery. A Spanish study published after the commencement of this research found that NOD2/CARD15 mutations are a predictive risk factor for surgical requirement due to stricturing lesions[21]. The proposed mechanism is that NOD2/CARD15 mutations predispose to stricturing and fibrotic lesions, and these altered repair mechanisms at the site of surgery would lead to earlier surgical recurrences, irrespective of the cause of initial surgery. It is also controversial whether the relationship between the CARD15 variants and both stenosing phenotype and increased need for surgery in CD patients is a true association or only reflects the high proportion of ileal CD developing bowel stenosis and, therefore, requiring surgery[32]. In our sample population, we found that patients with a NOD2/CARD15 pathogenic mutation had a higher frequency of operations than those without the mutation. This difference however was not statistically significant (P = 0.096) but showed a trend to more operations in mutation carriers. One limitation of the Spanish study is that it only analysed 23 patients who had subsequent surgery. Also, none of the recruited patients had more than 2 surgical resections. Although some of our patients have had up to 5 operations, our study is also limited by a small sample size. The lack of statistical significance in our study for this parameter of multiplicity of operations could therefore be explained by a Type II error.

These findings add strength to the argument supporting the use of NOD2/CARD15 genotyping as a prognostic tool in stratifying CD patients with a high risk of initial or subsequent operations. The ability to predict the natural history of high risk patients could prove useful in the application of top-down therapy, which may not just prevent complications but also modify the natural history of the disease[33,34]. Even if preventative therapy is ineffective, these high risk patients should be managed with close collaboration between physicians and surgeons. Most clinicians are not willing to adopt unrestricted top-down approach because a substantial proportion of patients never develop aggressive disease requiring biological therapy. The ability to predict those that will would be a great asset in the management of IBD given the effectiveness described by Oldenburg and Hommes[33]. This is in contrast to the conventional practice of starting with less invasive interventions and working up the therapeutic ladder, which in the long term may subject the patient to unnecessary and invasive investigations, medications and procedures. Genotyping may prove to have a place in contributing to what often is a quite complex decision-making especially since genetic-based classifications are stable compared to exclusive use of phenotypic characteristics which are subject to change over time.

However, it remains to be determined whether full NOD2/CARD15 gene sequencing during the diagnosis of CD will be clinically useful and cost effective. Most of the NOD2/CARD15 sequence variations identified in this study are rare and have not been found to influence the natural history of the disease. Our studies do suggest a place for at least the mutational analysis of the most common pathogenic mutations which can be done cheaply. From here, it would be useful to analyse whether NOD2/CARD15 mutations are able to predict response to therapy, particular biologics. Currently, there are no NOD2/CARD15 mutations that predict which patients might have sustained remission and which will relapse rapidly after stopping infliximab[35].

Furthermore, this study is of significant importance in highlighting the Australian population of Crohn’s patients who are ethically heterogenous and genetically diverse. In the present study, we observed allele frequencies of 13.3%, 3% and 16.7% for the 3020insC, G908R mutation and R702R mutations respectively. We were the first Australian study to conduct a full genotype sequencing of the NOD2/CARD15 gene (Table 3). We now know that there is great ethnic and geographical differences in the prevelance of NOD2/CARD15 mutations. The multicenter study published by Lesage et al[6], which included several European countries, reported a mutation carrier frequency of 50%. These findings have been replicated by other European studies .In Great Britain, the carrier frequency was found to be 38.5%[7], 46.3% in Belgium[36], 38.2% in Italy[25] , 38% in France[37], and 36.5% in Germany[20]. Conversely, there was a lack of mutant variants in the Asian populations of Japan[38], Korea[39], China[40,41] and India[42]. In one Malaysian study, none of the Malaysian patients with CD carried any of the NOD2/CARD15 pathogenic mutations[43,44].

We would expect the frequencies of the NOD2/CARD15 risk alleles found in our patients to be higher than in other studies due to the enrichment of NOD2/CARD15 variants within our cohort of patients with small bowel and ileo-caecal disease, both of which are disease locations associated with NOD2/CARD15 mutations. Furthermore, all patients in this cohort have had at least one surgical resection and have more severe disease (with surgery being a marker of severity), another clinical feature suggested to be a result of NOD2 mutations.

In our study, the presence of a NOD2/CARD15 mutation especially the 3020insC mutation, predicted a more aggressive form of disease which rapidly progressed and showed a trend towards the need for multiple surgical interventions and a significantly shorter time to surgery after diagnosis. Full sequencing may not be relevant for clinical management based on current information, but our results do suggest a place for initial genotyping of the 3 pathogenic mutations. Further confirmatory studies may suggest that a top-down therapy approach could be considered in mutation positive. There is substantial optimism that NOD2/CARD15 genotyping could be used in the development of clinical paradigms in the management of Crohn’s disease, especially guiding the need for more aggressive medical therapy or surgical intervention after diagnosis of CD.

Despite advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease (CD), little is known about the influence of the nucleotide-binding oligomerisation domain 2/caspase recruitment domains 15 (NOD2/CARD15) gene on the natural history of the disease with regard to the requirement for initial or subsequent surgery.

Most research studies conducted tend to carry out gene sequencing for the known pathogenic mutations, mainly due to cost limitations. This study was the first Australian study to conduct a full gene sequence of NOD2/CARD15 to try to identify novel mutations that may have a pathogenic role. The study was rewarded with new sequence variations of which there were 12 patients with a P268S sequence variation. 9 of these patients were heterozygous for the P268S variation and 3 were homozygous. Whilst not previously identified, the P268S change was not found to independently reduce the time between surgery and diagnosis (P = 0.067). It remains to be determined whether full NOD2/CARD15 gene sequencing during the diagnosis of CD will be clinically useful and cost effective. Most of the NOD2/CARD15 sequence variations identified in this study are rare and have not been found to influence the natural history of the disease.

In this study, it was found that a NOD2/CARD15 mutation predicted initial disease aggressiveness in CD with mutation positive patients having a significantly reduced time between the diagnosis of CD and initial surgery. There was also a trend to suggest that patients with the pathogenic mutations have a higher frequency of operations compared to those without the mutation. These findings were particularly significant in the presence of the 3020insC mutation.

This is an interesting manuscript. This study identify a new mutation INV2-25G in NOD2/CARD15 gene, which is reported previously.

P- Reviewers: Moreels TG, Rajendran VM S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Fiocchi C. Inflammatory bowel disease: etiology and athogenesis. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:182-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1493] [Cited by in RCA: 1485] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hugot JP, Laurent-Puig P, Gower-Rousseau C, Olson JM, Lee JC, Beaugerie L, Naom I, Dupas JL, Van Gossum A, Orholm M. Mapping of a susceptibility locus for Crohn’s disease on chromosome 16. Nature. 1996;379:821-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 649] [Cited by in RCA: 598] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:603-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3555] [Cited by in RCA: 3478] [Article Influence: 144.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cézard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O’Morain CA, Gassull M. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature. 2001;411:599-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4223] [Cited by in RCA: 3905] [Article Influence: 162.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hampe J, Cuthbert A, Croucher PJ, Mirza MM, Mascheretti S, Fisher S, Frenzel H, King K, Hasselmeyer A, MacPherson AJ. Association between insertion mutation in NOD2 gene and Crohn’s disease in German and British populations. Lancet. 2001;357:1925-1928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 769] [Cited by in RCA: 769] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lesage S, Zouali H, Cézard JP, Colombel JF, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O’Morain C, Gassull M, Binder V. CARD15/NOD2 mutational analysis and genotype-phenotype correlation in 612 patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:845-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 712] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahmad T, Armuzzi A, Bunce M, Mulcahy-Hawes K, Marshall SE, Orchard TR, Crawshaw J, Large O, de Silva A, Cook JT. The molecular classification of the clinical manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:854-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cuthbert AP, Fisher SA, Mirza MM, King K, Hampe J, Croucher PJ, Mascheretti S, Sanderson J, Forbes A, Mansfield J. The contribution of NOD2 gene mutations to the risk and site of disease in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:867-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Murillo L, Crusius JB, van Bodegraven AA, Alizadeh BZ, Peña AS. CARD15 gene and the classification of Crohn’s disease. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:59-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vermeire S, Wild G, Kocher K, Cousineau J, Dufresne L, Bitton A, Langelier D, Pare P, Lapointe G, Cohen A. CARD15 genetic variation in a Quebec population: prevalence, genotype-phenotype relationship, and haplotype structure. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:74-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Radlmayr M, Török HP, Martin K, Folwaczny C. The c-insertion mutation of the NOD2 gene is associated with fistulizing and fibrostenotic phenotypes in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2091-2092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bonen DK, Ogura Y, Nicolae DL, Inohara N, Saab L, Tanabe T, Chen FF, Foster SJ, Duerr RH, Brant SR. Crohn’s disease-associated NOD2 variants share a signaling defect in response to lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cavanaugh JA, Adams KE, Quak EJ, Bryce ME, O’Callaghan NJ, Rodgers HJ, Magarry GR, Butler WJ, Eaden JA, Roberts-Thomson IC. CARD15/NOD2 risk alleles in the development of Crohn’s disease in the Australian population. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bonen DK, Cho JH. The genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:521-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Economou M, Trikalinos TA, Loizou KT, Tsianos EV, Ioannidis JP. Differential effects of NOD2 variants on Crohn’s disease risk and phenotype in diverse populations: a metaanalysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2393-2404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bayless TM, Tokayer AZ, Polito JM, Quaskey SA, Mellits ED, Harris ML. Crohn’s disease: concordance for site and clinical type in affected family members--potential hereditary influences. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:573-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Polito JM, Childs B, Mellits ED, Tokayer AZ, Harris ML, Bayless TM. Crohn’s disease: influence of age at diagnosis on site and clinical type of disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:580-586. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Laghi L, Costa S, Saibeni S, Bianchi P, Omodei P, Carrara A, Spina L, Contessini Avesani E, Vecchi M, De Franchis R. Carriage of CARD15 variants and smoking as risk factors for resective surgery in patients with Crohn’s ileal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:557-564. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Heliö T, Halme L, Lappalainen M, Fodstad H, Paavola-Sakki P, Turunen U, Färkkilä M, Krusius T, Kontula K. CARD15/NOD2 gene variants are associated with familially occurring and complicated forms of Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2003;52:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Büning C, Genschel J, Bühner S, Krüger S, Kling K, Dignass A, Baier P, Bochow B, Ockenga J, Schmidt HH. Mutations in the NOD2/CARD15 gene in Crohn’s disease are associated with ileocecal resection and are a risk factor for reoperation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1073-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alvarez-Lobos M, Arostegui JI, Sans M, Tassies D, Plaza S, Delgado S, Lacy AM, Pique JM, Yagüe J, Panés J. Crohn’s disease patients carrying Nod2/CARD15 gene variants have an increased and early need for first surgery due to stricturing disease and higher rate of surgical recurrence. Ann Surg. 2005;242:693-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abreu MT, Taylor KD, Lin YC, Hang T, Gaiennie J, Landers CJ, Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, Rojany M, Papadakis KA. Mutations in NOD2 are associated with fibrostenosing disease in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:679-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hampe J, Grebe J, Nikolaus S, Solberg C, Croucher PJ, Mascheretti S, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Klump B, Krawczak M. Association of NOD2 (CARD 15) genotype with clinical course of Crohn’s disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:1661-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Brant SR, Panhuysen CI, Bailey-Wilson JE, Rohal PM, Lee S, Mann J, Ravenhill G, Kirschner BS, Hanauer SB, Cho JH. Linkage heterogeneity for the IBD1 locus in Crohn’s disease pedigrees by disease onset and severity. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1483-1490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Annese V, Lombardi G, Perri F, D’Incà R, Ardizzone S, Riegler G, Giaccari S, Vecchi M, Castiglione F, Gionchetti P. Variants of CARD15 are associated with an aggressive clinical course of Crohn’s disease--an IG-IBD study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:84-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ferreira AC, Almeida S, Tavares M, Canedo P, Pereira F, Regalo G, Figueiredo C, Trindade E, Seruca R, Carneiro F. NOD2/CARD15 and TNFA, but not IL1B and IL1RN, are associated with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:331-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Barreiro M, Núñez C, Domínguez-Muñoz JE, Lorenzo A, Barreiro F, Potel J, Peña AS. Association of NOD2/CARD15 mutations with previous surgical procedures in Crohn’s disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2005;97:547-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Seiderer J, Schnitzler F, Brand S, Staudinger T, Pfennig S, Herrmann K, Hofbauer K, Dambacher J, Tillack C, Sackmann M. Homozygosity for the CARD15 frameshift mutation 1007fs is predictive of early onset of Crohn’s disease with ileal stenosis, entero-enteral fistulas, and frequent need for surgical intervention with high risk of re-stenosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1421-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Maconi G, Colombo E, Sampietro GM, Lamboglia F, D’Incà R, Daperno M, Cassinotti A, Sturniolo GC, Ardizzone S, Duca P. CARD15 gene variants and risk of reoperation in Crohn’s disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2483-2491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kugathasan S, Collins N, Maresso K, Hoffmann RG, Stephens M, Werlin SL, Rudolph C, Broeckel U. CARD15 gene mutations and risk for early surgery in pediatric-onset Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1003-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lacher M, Helmbrecht J, Schroepf S, Koletzko S, Ballauff A, Classen M, Uhlig H, Hubertus J, Hartl D, Lohse P. NOD2 mutations predict the risk for surgery in pediatric-onset Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1591-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tsianos EV, Katsanos KH, Tsianos VE. Role of genetics in the diagnosis and prognosis of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:105-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 33. | Oldenburg B, Hommes D. Biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: top-down or bottom-up? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:395-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nasir BF, Griffiths LR, Nasir A, Roberts R, Barclay M, Gearry RB, Lea RA. An envirogenomic signature is associated with risk of IBD-related surgery in a population-based Crohn’s disease cohort. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1643-1650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lu C, Waugh A, Bailey RJ, Cherry R, Dieleman LA, Gramlich L, Matic K, Millan M, Kroeker KI, Sadowski D. Crohn’s disease genotypes of patients in remission vs relapses after infliximab discontinuation. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5058-5064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Esters N, Pierik M, van Steen K, Vermeire S, Claessens G, Joossens S, Vlietinck R, Rutgeerts P. Transmission of CARD15 (NOD2) variants within families of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Heresbach D, Gicquel-Douabin V, Birebent B, D’halluin PN, Heresbach-Le Berre N, Dreano S, Siproudhis L, Dabadie A, Gosselin M, Mosser J. NOD2/CARD15 gene polymorphisms in Crohn’s disease: a genotype- phenotype analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:55-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Inoue N, Tamura K, Kinouchi Y, Fukuda Y, Takahashi S, Ogura Y, Inohara N, Núñez G, Kishi Y, Koike Y. Lack of common NOD2 variants in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:86-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 326] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Croucher PJ, Mascheretti S, Hampe J, Huse K, Frenzel H, Stoll M, Lu T, Nikolaus S, Yang SK, Krawczak M. Haplotype structure and association to Crohn’s disease of CARD15 mutations in two ethnically divergent populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:6-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Leong RW, Armuzzi A, Ahmad T, Wong ML, Tse P, Jewell DP, Sung JJ. NOD2/CARD15 gene polymorphisms and Crohn’s disease in the Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1465-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Li M, Gao X, Guo CC, Wu KC, Zhang X, Hu PJ. OCTN and CARD15 gene polymorphism in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4923-4927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Pugazhendhi S, Amte A, Balamurugan R, Subramanian V, Ramakrishna BS. Common NOD2 mutations are absent in patients with Crohn’s disease in India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008;27:201-203. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Chua KH, Ng CC, Hilmi I, Goh KL. Co-inheritance of variants/mutations in Malaysian patients with Crohn’s disease. Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:3115-3121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Chua KH, Hilmi I, Ng CC, Eng TL, Palaniappan S, Lee WS, Goh KL. Identification of NOD2/CARD15 mutations in Malaysian patients with Crohn’s disease. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:124-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |