Published online Apr 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4329

Revised: September 24, 2013

Accepted: October 19, 2013

Published online: April 21, 2014

Processing time: 259 Days and 10.3 Hours

AIM: To explore the association between inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) flares and potential triggers.

METHODS: Patients evaluated for an acute flare of IBD by a gastroenterologist at the Dallas VA Medical Center were invited to participate, as were a control group of patients with IBD in remission. Patients were systematically queried about nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, antibiotic use, stressful life events, cigarette smoking, medication adherence, infections, and travel in the preceding 3 mo. Disease activity scores were calculated for each patient at the time of enrollment and each patient’s chart was reviewed. Multivariate regression analysis was performed.

RESULTS: A total of 134 patients with IBD (63 with Crohn’s disease, 70 with ulcerative colitis, and 1 with indeterminate colitis) were enrolled; 66 patients had flares of their IBD and 68 were controls with IBD in remission (for Crohn’s patients, average Crohn’s disease activity index was 350 for flares vs 69 in the controls; for UC patients, Mayo score was 7.6 for flares vs 1 for controls in those with full Mayo available and 5.4p for flares vs 0.1p for controls in those with partial Mayo score). Only medication non-adherence was significantly more frequent in the flare group than in the control group (48.5% vs 29.4%, P = 0.03) and remained significant on multivariate analysis (OR = 2.86, 95%CI: 1.33-6.18). On multivariate regression analysis, immunomodulator use was found to be associated with significantly lower rates of flare (OR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.19-0.86).

CONCLUSION: In a study of potential triggers for IBD flares, medication non-adherence was significantly associated with flares. These findings are incentive to improve medication adherence.

Core tip: Flares of Crohn’s disease and colitis are often unpredictable and physicians and patients alike search for triggers for these flares in an attempt to prevent future flares. In this study, we prospectively enrolled and queried patients with flares of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and compared their responses to IBD patients in remission. We found that medication non-adherence was the only significant trigger for flares of IBD, while nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, antibiotic use, infections, smoking, travel and emotional stress were not associated with flares. Clinicians should be aware the significant role that non-adherence plays in flare-ups of IBD in order to counsel their patients appropriately.

- Citation: Feagins LA, Iqbal R, Spechler SJ. Case-control study of factors that trigger inflammatory bowel disease flares. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(15): 4329-4334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i15/4329.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4329

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are lifelong ailments whose courses are characterized by recurring cycles of exacerbation and remission. These times of disease exacerbation, or flares, can be debilitating to patients causing significant pain and discomfort, need for hospitalization and/or surgery, and time lost from work and normal activities of daily life. A number of disparate factors (e.g., certain drugs, infections, tobacco, stress, and poor treatment adherence) have been proposed as triggers for flares of IBD. If physicians and patients were better able to identify modifiable triggers for these flares, these times of disease exacerbation might be fewer.

In some retrospective studies, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics has been associated with flares of IBD[1,2]. It has been proposed that NSAIDs might contribute to those flares by altering prostaglandin production, by increasing leukotriene production, or by altering nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling in the gut[1]. Antibiotics can alter bowel flora, which might promote flares by decreasing gut levels of protective bacteria or by increasing levels of potentially harmful microorganisms. Enteric infections associated with antibiotic use, such as Clostridium difficile, are now well known to be associated with IBD flares[3]. However, antibiotics also are used to treat active IBD (specifically CD), and there are some data to suggest that antibiotic use, at least in CD, actually might protect against flares[2]. Thus, the frequency with which NSAIDs and antibiotics contribute to IBD exacerbations remains unclear.

Tobacco usage, specifically active smoking in CD patients and smoking cessation in UC patients, has been linked to flares of IBD for reasons that are not clear[4,5]. Proposed mechanisms for the effects of tobacco use in IBD are numerous and include modulation of cellular and humoral immunity, changes in cytokine levels, modification of eicosanoid-mediated inflammation, reduction of antioxidant capacity, release of endogenous glucocorticoids, colonic mucus effects, alterations of mucosal blood flow, prothrombotic effects and promotion of microvascular thrombosis, alteration of gut permeability, and modification of gut motility[6]. Many patients blame emotional stress as the trigger for exacerbation of their IBD[7]. Some studies have demonstrated that experimental stress plays a role in activating gut inflammation in animal models of colitis[8,9]. Stress has been suggested to modulate the release of proinflammatory cytokines, to alter the activity of immune and inflammatory cells, and to increase gut permeability, all of which might exacerbate IBD[10]. Moreover, a survey of a population-based registry found that high-perceived stress was associated with an increased risk of flare[11]. Lastly, poor adherence with prescribed medications for IBD has been reported to increase the risk of flares. A systematic review on the use of 5-aminosalicylates in UC found the relative risk for a flare in nonadherent patients to be at least 3.65[12].

The veterans affairs (VA) health system offers a unique system in which to study patients in that the patients who served in the military simply have to enroll in the VA system and can receive free or low cost health care. No prior studies have addressed the question of triggers for flares in this unique population. We performed a case-control study to explore systematically the association between IBD flares and potential triggering factors in our veteran population.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dallas VA Medical Center. Informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

Between July 2009 and April 2012, all patients with flares of UC or CD who were evaluated by the Division of Gastroenterology during the course of their clinical care at the Dallas VA Medical Center, either in clinics or as inpatients, were invited to participate in this study. A control group of IBD patients followed in our IBD clinic who were in clinical remission for at least 6 mo also were invited to participate. Disease activity was measured at the time of enrollment using the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score (for CD patients) or the Mayo score (for UC patients) with CDAI > 150 or Mayo > 2 (or partial Mayo ≥ 2) defining a flare[13,14]. This was calculated by the study team at enrollment. Control patients were required to have CDAI < 150 or Mayo score ≤ 2 (or < 2 for partial Mayo). Patients were systematically queried about recent (within the previous 3 mo) infections (including upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal, urinary tract and skin infections), NSAID use, antibiotic use, stressful life events (divorce/separation, death in the family, birth of a child, loss or change of job, and other perceived stressful situations), pertinent tobacco use (discontinuation for UC, ongoing or starting smoking for CD patients), adherence with IBD-specific medications, and travel away from home. A written list of all potential NSAIDs, prescription and over-the-counter, was reviewed with the patient. Patients were queried with regard to how often they missed a dose of their IBD medications (on aggregate) and categorized as never, once per month, 2-4 times per month, 1-3 times per week, four or five times per week, or at least once a day. Patients were considered to be noncompliant with their medications if they missed a dose of medication at least 2-4 times per month. In addition to the data collected during the study enrollment, as detailed above, each patient’s chart was reviewed and data were collected with regard to recent laboratory work (within 1 mo), disease characteristics, and demographics. Repeat laboratory work was not mandated by study participation and data were only available if these tests were clinically indicated by their treating provider. Therefore, stool tests were typically collected only in patients with flares who were willing to produce a stool sample.

Analyses were performed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the unpaired t test (normally distributed) or Mann-Whitney test (not normally distributed) for continuous variables. Numbers are expressed as mean ± SD. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using SAS and the macro by Bursac and colleagues (2008) Purposeful Selection of Analyses[15]. The macro by Bursac and colleagues is a SAS algorithm that automates the variable selection process for logistic regression analysis. Any variable having a significant univariate test at P = 0.25 is selected as a candidate for the multivariate analysis. In the iterative process of variable selection, covariates are removed from the model if they are nonsignificant and not a confounder. Significance is evaluated at the 0.1 α level and confounding as a change in any parameter estimate > 20%. The macro allows the user to specify all decision criteria. At the end of this iterative process, the model contains significant covariates and confounders. At this point any variable not selected for the original multivariate model is added back one at a time, with significant covariates and confounders retained earlier. Any that are significant at the 0.1 level are put in the model, and the model is iteratively reduced as before but only for the variables that are additionally added. For the analysis of risk factors for flares, the variables evaluated were immunomodulator use, NSAID use, smoking, antibiotics, stress, non-adherence, infections, and travel. For the analysis of risk factors for non-adherence, the variables evaluated were type of medication used for IBD (5-ASA, immunomodulator, and biologics; too few patients were taking steroids or antibiotics to be included in the analysis), number of medications taken, age, disease type (UC or CD), disease duration, and race. Age was evaluated as a continuous variable. The final model for flares contained three retained predictors: immunomodulator use, non-compliance, and infection. The final model for non-compliance contained one retained predictor, age. This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, # NCT01405105.

A total of 134 patients with IBD (63 CD, 70 UC, and 1 indeterminate colitis) were enrolled in the study; 66 patients had flares of IBD and 68 were controls with IBD in remission. The two groups (flares and controls) had no significant differences with regard to age, sex, race, medication use, and disease type and location (Table 1). However, the use of immunomodulators (6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine or methotrexate) was significantly higher in the control group.

| Flares (n = 66) | Controls (n = 68) | P value | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 49.0 ± 14.3 | 53.1 ± 15.7 | 0.09 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr, mean ± SD) | 37.7 ± 13.6 | 39.3 ± 15.1 | 0.68 |

| Disease duration (yr, mean ± SD) | 12.1 ± 10.4 | 14.2 ± 11.4 | 0.15 |

| Sex (male/female) | 59/7 | 63/5 | 0.56 |

| Race | |||

| White | 49 (74.2) | 54 (79.4) | 0.54 |

| Black | 15 (22.7) | 12 (17.6) | 0.52 |

| Hispanic | 2 (3.0) | 2 (2.9) | 1.00 |

| Medication use | |||

| 5-ASAs | 50 (75.8) | 54 (79.4) | 0.68 |

| Immunomodulators | 17 (25.8) | 30 (44.1) | 0.03 |

| Biologics | 12 (18.2) | 15 (22.1) | 0.67 |

| Antibiotics | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| Steroids | 3 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0.12 |

| CD | 33 | 30 | |

| Colonic disease | 11 (16.7) | 8 (11.8) | 0.47 |

| Ileal disease | 9 (13.6) | 7 (10.3) | 0.60 |

| Ileocolonic | 12 (18.2) | 15 (21.1) | 0.67 |

| UC | 33 | 37 | |

| Extensive | 18 (27.3) | 19 (27.9) | 1.00 |

| Left-sided | 15 (22.7) | 13 (19.1) | 0.67 |

| Proctitis | 1 (1.5) | 5 (7.4) | 0.21 |

| Indeterminate colitis | 0 | 1 | 1.00 |

As would be expected, the mean CDAI score of the patients with flares of CD was significantly higher than that of control patients with CD in remission (356 vs 69, P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Similarly, the mean Mayo scores of patients with flares of UC were significantly higher than those of control patients with UC in remission (7.55 vs 1 in patients with a full Mayo score, and 5.41 vs 0.1 in those with a partial Mayo score, both P < 0.0001). In addition, the flare group had significantly lower hemoglobin and albumin levels, as well as significantly higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and higher erythrocyte sedimentation rates than the controls. Although routine stool studies were not done in our patients in remission, most those with exacerbation of their disease did have their stools analyzed. Of 40 assessed, two were positive for Clostridium difficile toxin (5%), none had a positive stool culture, and none had a positive stool evaluation for ova and parasites.

| Disease indices | Flares | Controls | P value |

| Average CDAI score (CD) | 349.8 ± 161.2 | 69.0 ± 52 | < 0.0001 |

| Average full Mayo score (UC)1 | 7.55 ± 2.9 | 1 ± 1.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Average partial Mayo score (UC)1 | 5.41p ± 1.8 | 0.1p ± 0.3 | < 0.0001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) (normal 0-1.0) | 3.48 ± 5.5 | 1.19 ± 1.7 | 0.0002 |

| ESR (MM/HR) (normal 0-30) | 29.9 ± 25.6 | 16.6 ± 17.5 | 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (normal 3.0-5.0) | 3.40 ± 0.7 | 3.85 ± 0.4 | < 0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (normal 11.5-15.3) | 13.1 ± 2.1 | 14.3 ± 1.6 | 0.0005 |

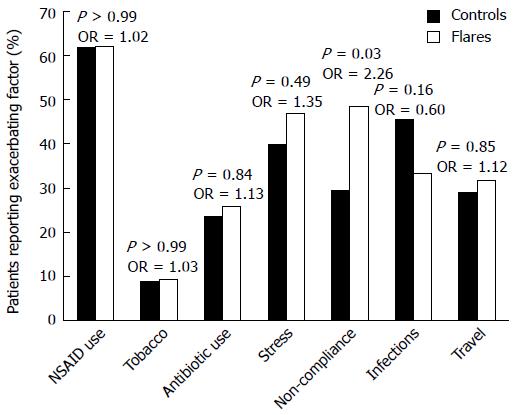

No significant differences between the flare and control groups were observed (Figure 1) for recent NSAID use (62.1% flares vs 61.8% controls, P > 0.99, OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.505-2.04), pertinent tobacco usage (9.1% flares vs 8.8% controls, P > 0.99, OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.316-3.384), recent antibiotic use (25.8% flares vs 23.5% controls, P = 0.84, OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 0.514-2.476), major life stressors (47.0% flares vs 39.7% controls, P = 0.49, OR = 1.35, 95%CI: 0.678-2.669), recent infections (33.3% flares vs 45.6% controls, P = 0.16, OR = 0.60, 95%CI: 0.296-1.202), and recent travel (31.8% flares vs 29.4% controls, P = 0.85, OR = 1.12, 95%CI: 0.537-2.336). Of all the potential triggers, only non-adherence with prescribed medication was significantly associated with IBD flares (48.5% flares vs 29.4% controls, P = 0.03, OR = 2.26, 95%CI: 1.110-4.599).

We performed separate subgroup analyses comparing the frequency of potential triggers in patients who had CD in the flare group with that in patients who had CD in the control group, and comparing the frequency of potential triggers in patients who had UC in the flare group with that in patients who had UC in the control group. There was no significant difference between flares and controls with CD in the frequency of medication non-adherence (39.4% flares vs 26.7% controls, P = 0.42). For patients with UC, however, medication non-adherence was significantly more frequent in the flare group (57.6% flares vs 32.4% controls, P = 0.05). Subgroup analyses for all other potential triggers revealed no significant differences between the flare and control groups.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that medication non-adherence and immunomodulator use were significantly associated with flares. The adjusted OR for medication non-adherence was 2.86 (95%CI: 1.33-6.18), indicating that patients who were not compliant were almost three times more likely to have a flare than those who took their medications as prescribed. The adjusted OR for immunomodulator use was 0.40 (95%CI: 0.19-0.86), indicating that patients using immunomodulators were 60% less likely to have a flare.

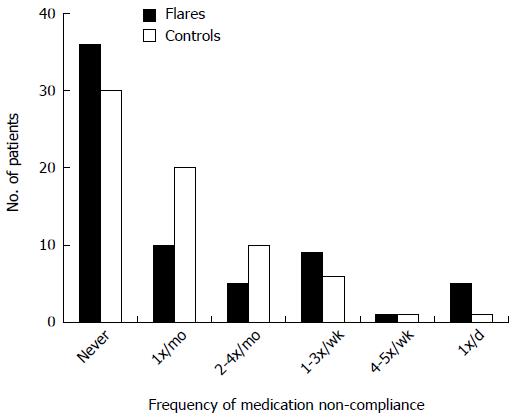

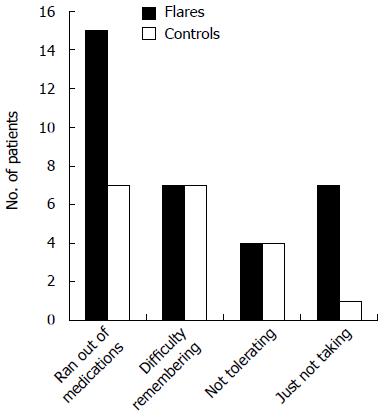

Patients were questioned regarding the frequency with which they missed doses of their medications. Approximately half of them admitted to missing a dose at least once a month or more, and 28.4% missed a dose at least 2-4 times per month or more. The most common reasons given for missing a dose was running out of medication or having difficulty remembering to take the medication (Figures 2 and 3).

We performed multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify predictors of non-adherence. We evaluated several factors that could contribute to non-adherence including: number of medications being prescribed for IBD, type of medications prescribed to treat IBD (5-ASA, immunomodulator, or biologics), age, disease type (CD or UC), disease duration, and race. Of these, only age was a significant predictor for non-adherence, with younger patients more likely to be noncompliant. When age was evaluated as a continuous variable, the OR for age was 0.96 (95%CI: 0.93-0.98), indicating that for every 1 year older, the patient was 4% more likely to be compliant. When evaluated on a yearly basis, for every 5 years older, the patient was 18.5% more likely to be compliant and for every decade older, the patient was 33.5% more likely to be compliant.

In this case-control study in which we systematically searched for a number of IBD triggers in our veteran patients with CD and UC, only medication non-adherence was significantly associated with flares of IBD. We found no significant differences between flare patients and controls in the frequency of other proposed triggers including recent infections, NSAID use, antibiotic use, stressful life events, travel away from home, and cigarette smoking. This is an interesting finding, particularly in a veteran population in which access to medications should not be a limiting factor. The two most common reasons reported for medication non-adherence were failure to refill medication prescriptions and forgetting to take the medications as prescribed. When the groups were subdivided by type of IBD (UC vs CD), non-adherence to medications remained a significant predictor of flare only for patients with UC. Multivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that non-adherence was significantly associated with flares, increasing the risk of flare almost threefold.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for predictors of non-adherence revealed only age to be a significant factor, with younger patients being less compliant. Specific medications (5-ASAs vs immunomodulators vs biologics), number of medications prescribed, disease type (UC vs CD), disease duration, and race did not significantly affect adherence.

Non-adherence to prescribed medication regimens is a common problem in patients with chronic diseases that require lifelong maintenance therapies. One study of patients with UC found that those who did not take their mesalamines as prescribed had a fivefold higher risk of flare than patients who were compliant with mesalamine therapy[16]. Another study explored factors associated with adherence in 106 IBD patients, and found lower adherence with medications dosed three or more times per day[17]. In our study, our patients taking mesalamines were dosed two or three times per day, because once-daily doses of mesalamine were not available at our institution during the time of this study. We assessed type of medication being taken (with the assumption that mesalamines are dosed several times per day), but found no increased risk of non-adherence for treatment with mesalamines as compared to other IBD treatments. The only factor that we identified as associated with non-adherence was younger age. These findings, in our unique study population of veterans, in which access to or cost of medications should not be a limiting factor, highlights the notion that other factors apart from cost or access are involved in non-adherence.

On multivariate regression analysis, immunomodulator use was found to be significantly associated with lower rates of flares. This did not seem to be related to adherence because we evaluated specific medications (5-ASAs vs immunomodulators vs biologics) in a multivariate analysis for predictors of non-adherence and did not find these to be a significant predictor. These findings suggest that using an immunomodulator lowers the risk of flares, at least in our population of patients.

The major limitation of our study was recall bias, because patients were queried and asked to remember possible triggers or exposures occurring in the preceding 3 mo. To minimize this potential bias regarding medication triggers, we reviewed the medical records to identify recent medications (NSAIDs and antibiotics) that were dispensed by the VA pharmacy. However, this review did not identify the use of over-the-counter drugs. NSAID use recall during patient interviews was assisted by reviewing with the patients a list of available proprietary NSAID medications that included their commercial and generic names. Medication adherence was also assessed by patient recall, as a written drug log was not possible with our study design of enrolling patients when they presented to the hospital or clinic with an IBD flare (i.e., patients could not be identified 3 mo prior to the start of a log). To minimize recall bias regarding medication adherence, we asked multiple questions about adherence including queries about the frequency of missing medications, of running out of medications, of problems in tolerating medications, and of failure to take the medication.

In conclusion, our study suggests that medication non-adherence is the most important of the proposed triggers for IBD flares. We found no association between flares and other putative triggers including NSAIDS, antibiotics, recent infections, tobacco use, travel and emotional stress. Our findings suggest that these factors either are not triggers at all, or are only weak triggers for IBD flares that might be identified only in much larger studies. Our report highlights the importance of medication adherence for patients with IBD.

Several factors have been proposed as triggers for flares of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including medications [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and antibiotics], infections, travel, emotional stress, tobacco use, and poor adherence with prescribed medications. Data implicating these factors have come largely from retrospective, uncontrolled studies.

A number of disparate factors (e.g., certain drugs, infections, tobacco, stress, and poor adherence) have been proposed as triggers for flares of IBD. Flares of IBD decrease quality of life greatly and carry a high burden of disease. If physicians and patients were better able to identify modifiable triggers for these flares, these times of disease exacerbation might be fewer.

The authors enrolled patients with IBD and active flares of their disease and queried them about exposure to potential triggers for their flares (NSAIDs, antibiotics, stress, tobacco use, medication adherence, infections, and travel). Disease activity indices were calculated and data on any available laboratory studies and endoscopy studies were collected. The authors also enrolled patients with IBD in remission and collected the same data.

The results suggest that medication non-adherence is the most important of the proposed triggers for flares of IBD. Moreover, use of an immunomodulator, such as azathioprine, mercaptopurine or methotrexate, was associated with a decreased risk of flares. Physicians should be aware of these findings to assist in counseling their patients on the importance of medication adherence.

This is a well written report of a case-control study that studied the association between IBD flares and potential triggering factors. The research question studied was an important one given the physical, emotional, and economic costs of disease relapse. The results are interesting and suggest that medication non-adherence is an important trigger for flares.

P- Reviewers: Adams SV, Chen JL, Fellermann K, Reigada LC, Vetvicka V S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Feagins LA, Cryer BL. Do non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs cause exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease? Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:226-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aberra FN, Brensinger CM, Bilker WB, Lichtenstein GR, Lewis JD. Antibiotic use and the risk of flare of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:459-465. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Issa M, Ananthakrishnan AN, Binion DG. Clostridium difficile and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1432-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cosnes J, Carbonnel F, Carrat F, Beaugerie L, Cattan S, Gendre J. Effects of current and former cigarette smoking on the clinical course of Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1403-1411. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Beaugerie L, Massot N, Carbonnel F, Cattan S, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Impact of cessation of smoking on the course of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2113-2116. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Birrenbach T, Böcker U. Inflammatory bowel disease and smoking: a review of epidemiology, pathophysiology, and therapeutic implications. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:848-859. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Vidal A, Gómez-Gil E, Sans M, Portella MJ, Salamero M, Piqué JM, Panés J. Life events and inflammatory bowel disease relapse: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:775-781. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Melgar S, Engström K, Jägervall A, Martinez V. Psychological stress reactivates dextran sulfate sodium-induced chronic colitis in mice. Stress. 2008;11:348-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Qiu BS, Vallance BA, Blennerhassett PA, Collins SM. The role of CD4+ lymphocytes in the susceptibility of mice to stress-induced reactivation of experimental colitis. Nat Med. 1999;5:1178-1182. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Singh S, Graff LA, Bernstein CN. Do NSAIDs, antibiotics, infections, or stress trigger flares in IBD? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1298-1313; quiz 1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bernstein CN, Singh S, Graff LA, Walker JR, Miller N, Cheang M. A prospective population-based study of triggers of symptomatic flares in IBD. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1994-2002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:525-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439-444. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1772] [Cited by in RCA: 2558] [Article Influence: 150.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39-43. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Bermejo F, López-San Román A, Algaba A, Guerra I, Valer P, García-Garzón S, Piqueras B, Villa C, Bermejo A, Rodríguez-Agulló JL. Factors that modify therapy adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:422-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |