Published online Apr 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4043

Revised: December 11, 2013

Accepted: January 3, 2014

Published online: April 14, 2014

Processing time: 180 Days and 5.2 Hours

AIM: To study possible gynecological organ pathologies in the differential diagnosis of acute right lower abdominal pain in patients of reproductive age.

METHODS: Following Clinical Trials Ethical Committee approval, the retrospective data consisting of physical examination and laboratory findings in 290 patients with sudden onset right lower abdominal pain who used the emergency surgery service between April 2009 and September 2013, and underwent surgery and general anesthesia with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis were collated.

RESULTS: Total data on 290 patients were obtained. Two hundred and twenty-four (77.2%) patients had acute appendicitis, whereas 29 (10%) had perforated appendicitis and 37 (12.8%) had gynecological organ pathologies. Of the latter, 21 (7.2%) had ovarian cyst rupture, 12 (4.2%) had corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture and 4 (1.4%) had adnexal torsion. Defense, Rovsing’s sign, increased body temperature and increased leukocyte count were found to be statistically significant in the differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis and gynecological organ pathologies.

CONCLUSION: Gynecological pathologies in women of reproductive age are misleading in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Core tip: Gynecological organ pathologies require to be taken into consideration when dealing with acute right lower abdominal pain in patients of reproductive age. We evaluated clinical and laboratory clues in the differential diagnosis of gynecological pathologies and acute appendicitis in patients of reproductive age. Defense, Rovsing’s sign, increased body temperature and increased leukocyte count were statistically significant in the differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis and gynecological organ pathologies. In women of reproductive age with acute abdominal pain, we should also consider the probability of gynecological pathologies, therefore, gynecological anamnesis and examination should be undertaken.

- Citation: Hatipoglu S, Hatipoglu F, Abdullayev R. Acute right lower abdominal pain in women of reproductive age: Clinical clues. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(14): 4043-4049

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i14/4043.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.4043

Abdominal pain constitutes 4%-8% of adult admissions to the emergency service[1,2]. For the patient admitted with right lower quadrant abdominal pain, acute appendicitis is the most frequently considered diagnosis. Appendicitis is a common cause of acute abdominal pain in women of reproductive age (WORA) and appendectomy is the most common of all emergency operations carried out in these patients[3]. Moreover, suspected appendicitis is one of the most common surgical consultations in the outpatient or emergency room setting.

Appendicitis is an emergency situation with the highest rate of misdiagnosis, even though clear diagnosis and treatment strategies have been established for more than 100 years[4]. The inconsistency between disease severity and physical findings is greater in older patients and WORA relative to other groups. This inconsistency further increases in WORA due to gynecological pathologies mimicking acute appendicitis[5-10]. The diagnosis and management of WORA with acute appendicitis remain a difficult challenge for general surgeons and gynecologists. General surgeons may challenge gynecological pathologies and may have to intervene in these circumstances in women undergoing laparotomy with the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

A thorough understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the abdomen is essential to properly generate a differential diagnosis and to formulate a treatment plan. Acute appendicitis can lead to unwanted complications if the diagnosis is confused or delayed. Although recent advances in surgical and diagnostic technology can be extremely helpful in certain situations, they cannot replace a surgeon’s clinical judgment based on good anamnesis and physical examination.

Today, with medicine becoming more dependent on laboratory and radiological findings the merit of physical examination has decreased. It is important to understand that painstaking anamnesis and physical examination is important and may be diagnostic for many diseases, especially appendicitis. In our study, we wanted to present and emphasize how definitive anamnesis, physical examination and laboratory findings carry clues for the differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis and gynecological obstetric pathologies in WORA.

Following Clinical Trials Ethical Committee approval, the retrospective data consisting of physical examination and laboratory findings of 290 female patients with sudden onset right lower abdominal pain who used the emergency surgery service of Adiyaman University Training and Research Hospital between April 2009 and September 2013, and underwent surgery under general anesthesia with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis were collated. The data consisted of the first findings obtained at admission and included the presence of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia for anamnesis; abdominal tenderness, defense, rebound, Dunphy’s sign, obturator sign, psoas sign, and Rovsing’s sign for physical examination; and body temperature, leukocyte count, urine microscopy and abdominal X-ray for laboratory findings. Emergency abdominal ultrasonography (USG) and computerized tomography (CT) were not routinely performed in these patients due to an insufficiency of radiological consultation out-of-shift.

The first examination and surgery in these patients were performed by the same general surgeon. All patients underwent routine preoperative gynecological consultation. Preoperatively, the patients received a prophylactic dose of 2nd generation cephalosporin (1 g iv) and underwent an open approach appendectomy via a McBurney incision under general anesthesia. A laparoscopic approach was not performed due to technical inadequacy. Diagnosis of appendicitis and gynecological pathology was made by perioperative macroscopic evaluation. Abdominal exploration was carried out in all patients with normal appendix to exclude possible Meckel’s diverticulum. Perioperative gynecological consultation was obtained for patients with gynecological pathology. Patients with previous abdominal or gynecological surgery, patients without normal menstrual cycle and pregnant patients were excluded from the study. Patients with gynecological pathologies were discharged and it was suggested that they attend a gynecology polyclinic.

All values were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Qualitative data were analyzed using the χ2 test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) 9.05 for Windows® statistical package.

The mean age of the patients was 21.4 ± 3.6 years (12-44 years). Total data for 290 patients were obtained. Two hundred and twenty-four (77.2%) had acute appendicitis, whereas 29 (10%) had perforated appendicitis and 37 (12.8%) had gynecological organ pathologies. Of the latter, 21 (7.2%) had ovarian cyst rupture, 12 (4.2%) had corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture and 4 (1.4%) had adnexal torsion (Table 1).

| Parentheses | Patients (n = 290), n (%) | Age (yr) |

| Acute appendicitis | 224 (77.2) | 21 (12-44) |

| Perforated appendicitis | 29 (10) | 22 (14-42) |

| Ovarian cyst rupture | 21 (7.2) | 24 (15-38) |

| Corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture | 12 (4.2) | 21 (13-35) |

| Adnexal torsion | 4 (1.4) | 24 (19-30) |

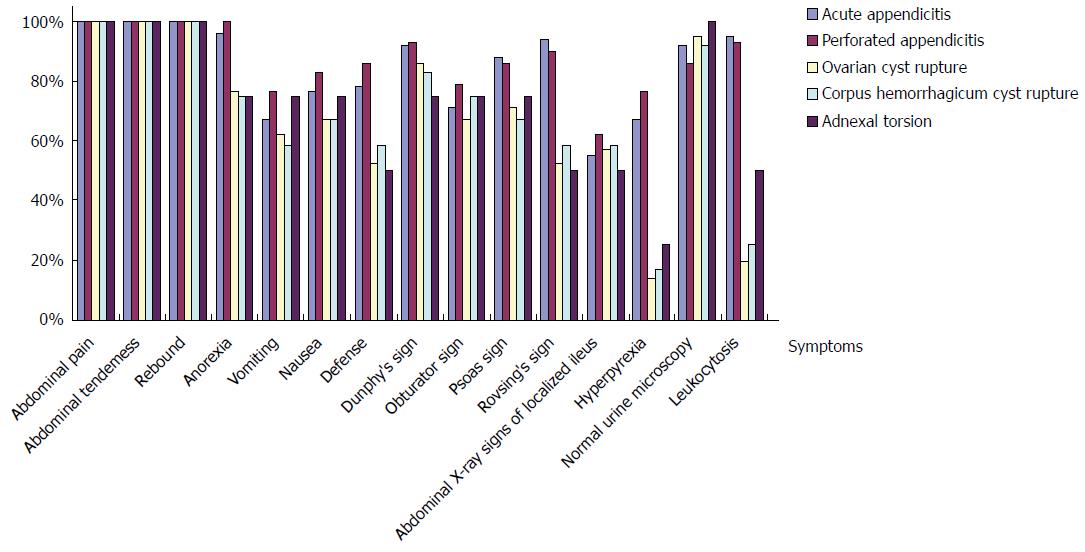

All patients had abdominal pain with right lower abdominal region tenderness and rebound as the first signs on physical examination (Figure 1). Defense, Rovsing’s sign, increased body temperature (hyperpyrexia) and increased leukocyte count (leukocytosis) were found to be statistically significant in the differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis and gynecological organ pathologies (Figure 1).

All patients underwent appendectomy. Patients with normal appendix at exploration who were found to have ovarian cyst rupture underwent cauterization, ovary primary suturation and cyst excision in 16 (76.2%), 4 (19%) and 1 (4.8%) patients, respectively. Six (50%), 2 (16.7%) and 4 (43.3%) patients with corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture underwent cauterization, ovary primary suturation and cyst excision, respectively. Three patients with adnexal torsion underwent detorsion and oophoropexy, whereas 1 patient underwent oophorectomy and salpingectomy (Table 2). No postoperative mortality was observed in these patients. Morbidity was observed in 11 patients (3.8%), 2 (18.2%) patients developed atelectasis and 9 (81.8%) patients developed wound infection.

| Treatment | Ovarian cyst rupture | Corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture | Adnexal torsion |

| Cauterization | 16 (76.2) | 6 (50.0) | 0 |

| Primary suturation | 4 (19.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0 |

| Cyst excision | 1 (4.8) | 4 (43.3) | 0 |

| Detortion + oophoropexy | 0 | 0 | 3 (75) |

| Oophorectomy + salpingectomy | 0 | 0 | 1 (25) |

Acute appendicitis is an important cause of acute abdominal pain. The incidence of appendicitis in all age groups is 7%[11,12]. The incidence of appendicitis in men and women is 8.6% and 6.7%, respectively[13]. Appendicitis is most commonly seen in subjects aged 10-30 years[14]. The mean age of the patients in our study was 21.3 ± 3.7 years. The frequency of appendicitis in males and females is equal in childhood, whereas the incidence in males increases with age with a male/female ratio of 3:2 in adulthood[15,16].

The diagnosis of acute appendicitis is made by anamnesis and clinical findings. Although it can vary with age and sex; correct diagnosis can be made in 70%-80% of patients via anamnesis, physical examination and laboratory findings[17-19]. Diagnostic accuracy decreases in WORA, in children and the elderly[20]. Laboratory findings and radiological examination can support the diagnosis of appendicitis, but can never rule it out. The symptoms of acute appendicitis generally follow a certain sequence and include periumbilical pain (visceral, unlocalized), anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, right lower quadrant abdominal pain and tenderness, hyperpyrexia, and leukocytosis. These symptoms may not to be present at the same time. Physical findings suggesting appendicitis are McBurney tenderness, rebound, Rovsing’s sign, Dunphy’s sign, psoas sign, obturator sign and fullness and tenderness in the pelvis during digital rectal examination[17-19].

We used Dunphy’s sign (increased right lower quadrant pain with coughing), obturator sign (increased pain with flexion and internal rotation of the hip), psoas sign (increased pain with passive extension of the right hip which can be elicited with the patient lying on the left side), and Rovsing’s sign (increased right lower quadrant pain during palpation in the left lower quadrant) as the most common physical examination findings of appendicitis in our study[21].

The main symptoms of acute appendicitis are frequently periumbilical pain preceded by anorexia and nausea. Vomiting is generally seen later. The pain generally switches to the right lower abdominal quadrant 8 h after the initial pain[22]. The Surgical Infection Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America published guidelines that recommend the establishment of local pathways for the diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis[21,23]. According to these guidelines, the combination of clinical and laboratory findings of characteristic acute abdominal pain, localized tenderness, and laboratory evidence of inflammation will identify most patients with suspected appendicitis[21]. Our findings are shown in Figure 1.

Although the clinical presentation of periumbilical pain migrating to the right lower abdominal quadrant is classically associated with acute appendicitis, the presentation is rarely typical and the diagnosis cannot always be based on medical history and physical examination alone. Classical clinical findings of appendicitis are observed in only 60% of patients with acute appendicitis, whereas 20%-33% display atypical clinical and laboratory findings[22]. Regardless of the technological advances in the preoperative diagnosis of acute appendicitis, the correct diagnosis can only be made in 76%-92% of cases[24,25]. On the other hand, 6%-25% of operations for acute appendicitis reveal normal appendix and this number can reach 30%-40% in WORA[26-30]. Normal appendix was observed in 12.8% of patients in the present study. Diagnostic errors are common, with over-diagnosis leading to negative appendectomies and delays in diagnosis leading to perforations. Diagnostic strategies for evaluating patients with acute abdominal pain and for identifying patients with suspected appendicitis should start with a painstaking anamnesis and physical examination. All of our patients had abdominal pain with right lower abdominal region tenderness and rebound as the first signs on physical examination (Figure 1). Defense, Rovsing’s sign, increased body temperature and increased leukocyte count were found to be statistically significant in the differential diagnosis of appendicitis and gynecological organ pathologies (Figure 1).

The accurate diagnosis of acute abdominal pain related to adnexal pathologies is very important for morbidity and mortality. It is also crucial to choose the right treatment modality which can affect the hospitalization period and patient satisfaction. Moreover, the cost of the optimum treatment modality is important and should not be neglected. The fertility of patients can be affected when no intervention is performed for gynecological pathologies in negative appendectomy cases[31]. We observed ovarian cyst rupture, corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture and adnexal torsion in our study.

Pelvic pain during the ovulatory cycle may be observed due to a small amount of blood which drains from the ruptured ovarian follicle to the peritoneal cavity during ovulation. This pain is mild-to-moderate and limited, and hemoperitoneum is seldom observed with normal hemostatic parameters. Thus, there is generally no need for surgical intervention in these circumstances[32]. It is crucial to make an early correct diagnosis and to execute careful observation in patients thought to have ovarian cyst rupture if exploratory surgical intervention may result in future infertility. Adnexal masses in adolescents contain functional and physiologic cystic formations at one end of the spectrum, and serious malignant tumors at the other end. The principal clinical approach in these adnexal pathologies is to preserve organs and fertility.

Ovarian cyst rupture occurs due to benign or malignant cystic lesions of the ovaries. Cyst excision is a convenient treatment choice in young patients. It is important not to remove the whole ovary. Oophorectomy can be performed in older patients. It should be taken into consideration, that young patients with ovarian germ cell tumors may be associated with acute abdomen[5]. Hemodynamic parameters in patients with ovarian cyst rupture may be impaired due to blood loss[31,33]. Suturation, cauterization of the bleeding site or cyst excision can be performed for ovarian cyst rupture[33]. Ovarian cyst rupture was observed in 7.2% of patients in our study (Table 2). Hemodynamic parameters in these patients were stable and there was no need for blood transfusion.

Corpus hemorrhagicum cysts are one of the most common ovarian cysts. They are formed as a result of hemorrhage into the follicle cyst or corpus luteum cyst in the ovaries during the ovulation period[34-38]. The clinical signs and symptoms are variable and include patients who are asymptomatic or patients with symptoms of acute abdomen[34]. These cysts are commonly seen in a single ovary, and are rarely observed bilaterally. They are more frequently seen in patients undergoing ovulation therapy for pregnancy. They are also seen in patients with bleeding disorders and coagulation problems or those on anticoagulant treatment. They may require surgery due to intraabdominal hemorrhage as a result of rupture or torsion[36-38]. In general, bleeding can be stopped by excision of the cyst, however, sometimes the ovary needs to be removed. We observed corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture in 4.2% of the patients in our study (Table 1). All of these patients had stable hemodynamics and did not require blood transfusion. The patients were in their 20s and in their active reproductive period, which is in accordance with the literature[39].

Adnexal torsion is a well-known, but difficult to diagnose cause of acute abdomen due to variable clinical causes and symptoms, and involves the tuba folding up on itself. Clinical findings are similar to those of acute appendicitis[40-42]. Ovarian torsion is observed in 2%-3% of patients undergoing surgery with a diagnosis of acute appendicitis[40,41,43,44]. Ovarian torsion was observed in 1.4% of patients in the present study (Table 1). It is observed 3-fold more frequently on the right compared with the left side[40,41]. It is relatively easy to differentiate ovarian torsion from other causes of acute abdomen via ultrasonography during the early period[45,46]. Adnexal torsions without symptoms are dangerous and caution should be taken in these cases. Removal of the adnex and eventual infertility risk is likely.

Excision of necrotic tissue is suggested before detorsion, due to the risk of pulmonary thromboembolism (0.2%), if vividness of the ovary is lost and a gangrene demarcation line has already formed[47,48]. In our study, we observed one patient in whom the ovary had lost its normal structure and had a necrotic appearance, and oophorectomy was performed before detorsion. Another three patients with ovarian torsion underwent detorsion and ovarian fixation (Table 2). Cohen et al[49] reported that torsioned, ischemic and hemorrhagic adnexa can be detorsioned laparoscopically with minimal morbidity and complete recovery of ovarian function.

The diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is generally quick and easy following the measurement of β-hCG. We did not encounter ectopic pregnancy rupture in our study, which constitutes a significant proportion of gynecological emergencies. The reason for this may have been due to painstaking anamnesis of the patients regarding their marriage, chance of pregnancy, β-hCG values and clinical differences between ectopic pregnancy and acute appendicitis.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) and CT are important in establishing the diagnosis of acute appendicitis preoperatively[50-52]. CT must be used to support the diagnosis and exclude other possible causes following clinical and laboratory diagnosis. Nevertheless, the ratio of negative appendectomies is higher than expected. Abdominal US, which is easy applied, inexpensive and noninvasive is the preferred method[50]. Abdominal CT is more valuable than US in this respect; the accuracy of US in the diagnosis of appendicitis is 71%-97% due to dependence on the operator and patient factors such as obesity, whereas that of CT is 93%-98%[20]. Emergency abdominal US and CT were not routinely performed in our patients due to an insufficiency of radiological consultation out-of-shift.

Leukocytosis is observed in 80%-90% of appendicitis cases, however, leukocyte number is below 18.000 mm3 unless perforation is present[53]. Yang et al[54] showed a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 31.9% for leukocyte count in appendicitis. In the present study, leukocyte counts were high in patients with acute and perforated appendicitis at 95% and 93%, respectively (Figure 1).

Currently, increased knowledge and experience, together with the development of imaging methods and laboratory techniques to evaluate patients with a gynecological emergency have facilitated the necessary general measures to minimize morbidity and mortality. When tailoring management strategies, the development and psychology of the reproductive women should be considered as well as preserving fertility which is the ultimate aim of treatment. Taking subsequent therapy into consideration, a multidisciplinary (general surgeon, gynecologist and radiologist) approach should be the basis of the management of adnexal pathologies.

In conclusion, acute appendicitis is one of the most frequent causes of acute abdomen and is also the most frequent abdominal surgical procedure. Ensuring a detailed anamnesis and medical examination is very important in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Laboratory findings and imaging techniques may be useful in the diagnosis. However, the diagnosis of acute appendicitis is made mainly by clinical history and clinical findings. Laboratory findings and imaging techniques support the diagnosis, but can never exclude acute appendicitis. Before establishing the diagnosis of acute appendicitis it should be remembered that gynecological pathologies may be present in WORA. Clinical findings are not always enough for definitive diagnosis and negative laparotomy is sometimes inevitable in WORA. Moreover, in view of the legal repercussions for general surgeons as a result of erroneous diagnosis and treatment, we think that adequate evaluation of the studies carried out by the emergency surgery service is important and that radiological investigations (abdominal US and CT) need to be used appropriately and sufficiently.

Clinical and laboratory clues in the differential diagnosis of gynecological pathologies are most likely to be confused with acute appendicitis in women of reproductive age. In these women with acute abdominal pain, the probability of gynecological pathologies should be considered, therefore gynecological anamnesis and gynecological examination should be undertaken.

Evaluation of clinical and laboratory clues in the differential diagnosis of gynecological pathologies are most likely confused with acute appendicitis in women of reproductive age.

Although recent advances in medical technology can be extremely helpful in the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen, they must not replace the clinical judgment a general surgeon based upon good anamnesis and physical examination.

In this study the authors evaluate the acute right lower quadrant abdominal pain in women of reproductive age that continues to be an open problem in general surgery. This original article is very attractive and useful.

P- Reviewers: Braden B, Ince V, Radojcic BS S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Powers RD, Guertler AT. Abdominal pain in the ED: stability and change over 20 years. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:301-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nelson MJ, Pesola GR. Left lower quadrant pain of unusual cause. J Emerg Med. 2001;20:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Flum DR, Koepsell TD. Evaluating diagnostic accuracy in appendicitis using administrative data. J Surg Res. 2005;123:257-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pegoli W. Acute appendicitis. Current surgical therapy. 6th Edition. St Louis: Mospy 1998; 263-266. |

| 5. | Nakhgevany KB, Clarke LE. Acute appendicitis in women of childbearing age. Arch Surg. 1986;121:1053-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Colson M, Skinner KA, Dunnington G. High negative appendectomy rates are no longer acceptable. Am J Surg. 1997;174:723-726; discussion 726-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Espinoza R, Ohmke J, García-Huidobro I, Guzmán S, Azocar M. [Negative appendectomy: experience at a university hospital]. Rev Med Chil. 1998;126:75-80. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Fingerhut A, Yahchouchy-Chouillard E, Etienne JC, Ghiles E. [Appendicitis or non-specific pain in the right iliac fossa]. Rev Prat. 2001;51:1654-1656. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kahrau S, Foitzik T, Klinnert J, Buhr HJ. [Acute appendicitis. Analysis of surgical indications]. Zentralbl Chir. 1998;123 Suppl 4:17-18. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Khairy G. Acute appendicitis: is removal of a normal appendix still existing and can we reduce its rate. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:167-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lau WY, Fan ST, Yiu TF, Chu KW, Lee JM. Acute appendicitis in the elderly. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;161:157-160. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Horattas MC, Guyton DP, Wu D. A reappraisal of appendicitis in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1990;160:291-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Hawkins RE, Bredenberg CE. Abdominal vascular catastrophes. Surg Clin North Am. 1997;77:1305-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shelton T, McKinlay R, Schwartz RW. Acute appendicitis: current diagnosis and treatment. Curr Surg. 2003;60:502-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cueto J, Díaz O, Garteiz D, Rodríguez M, Weber A. The efficacy of laparoscopic surgery in the diagnosis and treatment of peritonitis. Experience with 107 cases in Mexico City. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:366-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Diethelm AG, Standley RJ. Robbin ML. Texbook of Surgery. 15th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders 1997; 825-846. |

| 17. | Howell JM, Eddy OL, Lukens TW, Thiessen ME, Weingart SD, Decker WW. Clinical policy: Critical issues in the evaluation and management of emergency department patients with suspected appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:71-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ebell MH. Diagnosis of appendicitis: part 1. History and physical examination. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:828-830. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Humes DJ, Simpson J. Acute appendicitis. BMJ. 2006;333:530-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Old JL, Dusing RW, Yap W, Dirks J. Imaging for suspected appendicitis. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:71-78. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Wray CJ, Kao LS, Millas SG, Tsao K, Ko TC. Acute appendicitis: controversies in diagnosis and management. Curr Probl Surg. 2013;50:54-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ma KW, Chia NH, Yeung HW, Cheung MT. If not appendicitis, then what else can it be A retrospective review of 1492 appendectomies. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:12-17. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, Rodvold KA, Goldstein EJ, Baron EJ, O’Neill PJ, Chow AW, Dellinger EP, Eachempati SR. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2010;11:79-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Andersson RE, Hugander A, Ravn H, Offenbartl K, Ghazi SH, Nyström PO, Olaison G. Repeated clinical and laboratory examinations in patients with an equivocal diagnosis of appendicitis. World J Surg. 2000;24:479-485; discussion 485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Walker AR, Segal I. What causes appendicitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:127-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Paulson EK, Kalady MF, Pappas TN. Clinical practice. Suspected appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:236-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Flum DR, Koepsell T. The clinical and economic correlates of misdiagnosed appendicitis: nationwide analysis. Arch Surg. 2002;137:799-804; discussion 804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hardin DM. Acute appendicitis: review and update. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:2027-2034. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Hoffman D. Aids in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 1989;74:774-779. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Singhal V, Jadhav V. Acute appendicitis: are we over diagnosing it. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:766-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kamin RA, Nowicki TA, Courtney DS, Powers RD. Pearls and pitfalls in the emergency department evaluation of abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:61-72, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | LeMaire WJ. Mechanism of mammalian ovulation. Steroids. 1989;54:455-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Evsen MS, Soydinc HE. Emergent gynecological operations: A report of 105 cases. J Clin Exp Invest. 2010;1:12-15. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nemoto Y, Ishihara K, Sekiya T, Konishi H, Araki T. Ultrasonographic and clinical appearance of hemorrhagic ovarian cyst diagnosed by transvaginal scan. J Nippon Med Sch. 2003;70:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | CLAMAN AD. Bleeding from the ovary: graafian follicle and corpus luteum. Can Med Assoc J. 1957;76:1036-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hoyt WF, Meigs JV. Rupture of the graffian follicle and corpus luteum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1963;62:114-118. |

| 37. | Yoffe N, Bronshtein M, Brandes J, Blumenfeld Z. Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst detection by transvaginal sonography: the great imitator. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1991;5:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bass IS, Haller JO, Friedman AP, Twersky J, Balsam D, Gottesman R. The sonographic appearance of the hemorrhagic ovarian cyst in adolescents. J Ultrasound Med. 1984;3:509-513. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Rapkin AJ. Pelvic pain and dismenorrea. Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2004; 399-403. |

| 40. | Burnett LS. Gynecologic causes of the acute abdomen. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:385-398. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Hibbard LT. Adnexal torsion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;152:456-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nichols DH, Julian PJ. Torsion of the adnexa. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1985;28:375-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mage G, Canis M, Manhes H, Pouly JL, Bruhat MA. Laparoscopic management of adnexal torsion. A review of 35 cases. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:520-524. [PubMed] |

| 44. | van der Zee DC, van Seumeren IG, Bax KM, Rövekamp MH, ter Gunne AJ. Laparoscopic approach to surgical management of ovarian cysts in the newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:42-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Tepper R, Zalel Y, Goldberger S, Cohen I, Markov S, Beyth Y. Diagnostic value of transvaginal color Doppler flow in ovarian torsion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;68:115-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Davis LG, Gerscovich EO, Anderson MW, Stading R. Ultrasound and Doppler in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Eur J Radiol. 1995;20:133-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kurzbart E, Mares AJ, Cohen Z, Mordehai J, Finaly R. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube in premenarcheal girls. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1384-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Stenchever M, Droegemueller W, Herbst A, Mishell D. Benign gynecologic lesions. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Publishing Company 2001; 519-520. |

| 49. | Cohen SB, Oelsner G, Seidman DS, Admon D, Mashiach S, Goldenberg M. Laparoscopic detorsion allows sparing of the twisted ischemic adnexa. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Balthazar EJ, Birnbaum BA, Yee J, Megibow AJ, Roshkow J, Gray C. Acute appendicitis: CT and US correlation in 100 patients. Radiology. 1994;190:31-35. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Dueholm S, Bagi P, Bud M. Laboratory aid in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. A blinded, prospective trial concerning diagnostic value of leukocyte count, neutrophil differential count, and C-reactive protein. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:855-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lau WY, Fan ST, Yiu TF, Chu KW, Wong SH. Negative findings at appendectomy. Am J Surg. 1984;148:375-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Jaffe BM, Berger DH. Appendics. Schwartz‘s Principles of Surgery. 8th edition. New York: Mc Graw-hill 2004; 1119-1139. |

| 54. | Yang HR, Wang YC, Chung PK, Chen WK, Jeng LB, Chen RJ. Laboratory tests in patients with acute appendicitis. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |