INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B is defined as the presence of HBsAg and elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels for more than 6 mo, along with distinctive necroinflammation in the liver[1].

More than 240 million people have chronic hepatitis B in the world, with the highest incidence in sub-Saharan African and East Asian regions[2]. In China, approximately 120 million people are hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers[3]. Most people in HBV prevalent countries become infected with HBV during childhood, which becomes a financial burden of governments, especially in East Asia.

The universal vaccination program has reduced the prevalence rate of hepatitis B, especially in children. The seroprevalence of HBsAg in Korean children decreased to 0.2% of preschool children and 0.44% of early teenage students in 2007 owing to the universal vaccination and hepatitis B perinatal transmission prevention program[1]. In Taiwanese children (< 15 years of age), the rate of HBsAg positivity dropped to 0.6% after the successful implementation of universal vaccination for 20 years, compared to 10% in the pre-vaccination era[4].

However, treatment is not always easy because of inattention to the natural course of chronic hepatitis B in children and emerging antiviral drug resistance. It is essential to minimize the severity of active hepatitis and reduce the length of the immune clearance phase, and avoid inappropriate treatment or negligence. Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion does not indicate histologic remission of chronic hepatitis. Currently, medications for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B infections are conventional interferon (IFN), lamivudine and adefovir in children. Global studies on potent antiviral agents such as entecavir and tenofovir in children are ongoing; however, these drugs need approved as the primary treatment option in children.

In the meanwhile, there are still a lot of misconception about the natural course, diagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis B, especially in children. “Children are not little adults” is a true sentence for chronic hepatitis B. In the East where vertical infection is a major transmission mode, it is difficult to determine the facts on the basis of western journal articles. The authors have reviewed published articles comparing Asian children to adults as well as to western children, especially in the management and treatment of chronic hepatitis B in children.

NATURAL COURSE OF CHRONIC HEPATITIS B

After acute HBV exposure, 90% of infants of HBeAg seropositive mothers become chronic HBV carriers, whereas 25%-70% of children aged < 3-5 years and 5% of adults become chronic carriers[5-7]. The immature immune system in young children may be accountable for this.

Chronic hepatitis B in children with HbsAg positivity for at least six months is transmitted predominantly through vertical infection[7]. In this case, the initial phase is the immune tolerance phase, in which HBeAg is positive and the serum HBV DNA level is over 105 copies/mL (over 107-1010 copies/mL in practice) due to a high level of HBV replication; however HBV carriers are generally asymptomatic with normal aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/ALT values. Liver damage is minimal regardless of the active HBV replication rate during this phase, for HBV is a virus that does not attack hepatocytes directly[8].

As the stage progresses onto the immune clearance phase (immune active phase), accompanied by necrosis of liver tissues, ALT rises due to the transaminase that comes from the damaged hepatocytes. This results in chronic active hepatitis with HBeAg positivity and fluctuation of serum HBV DNA level, complicated by necrosis and fibrosis of liver tissues. The majority of patients who have been vertically transmitted progress into chronic active hepatitis before the age of 35. Though liver damage is usually mild in children, liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma may even develop as complications 2-7 years after vertical infection[9,10].

At the end of the immune clearance phase and transition to the non/low replicative phase, removal of infected hepatocytes results in low HBV DNA and HBeAg seroconversion[11]. Also known as the inactive HBV carrier state, serum aminotransferase normalizes and serum HBV DNA also declines to the level of less than 2000 IU/mL (104 copies/mL). Whilst 2/3 of untreated inactive carriers stay in the non (low) replicative phase for a prolonged period, this is important to note since approximately 20% of untreated inactive carriers may go through the reactivation phase, some through repetitive hepatitis flares, and 4% may revert to HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B[12,13]. However, these kinds of acute exacerbation are unusual in children after HBeAg seroconversion[14].

SPONTANEOUS HBEAG/ANTI-HBE SEROCONVERSION

It is rare for HBeAg to spontaneously seroconvert during the immune tolerance phase. Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion occurs during the immune clearance phase. It takes place at different periods of life from childhood to the 5th decade, but most commonly between the ages of 15 and 30 years. Ages ranging from thirties to forties are the most common in Asian countries where vertical transmission is the major route, due to the slower development of the immune clearance phase[12].

The rate of spontaneous seroconversion is lower in children than in adults. Spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion has been shown to be less than 2% annually in children aged < 3 years, which increases to 4%-5% over the age of 3, and 10%-14% for the 10-14 year age group in Taiwan[15]. In South Korea, HBeAg clearance occurs in around one third of HBV infected children by 19 years of age[16].

In Asia, the major mode of HBV infection is usually via vertical transmission which leads to a prolonged immune-tolerant phase. That may explain why the spontaneous seroconversion rate is low in Asia compared to western countries. Higher HBeAg seroconversion rates have been reported in children infected horizontally than in those infected perinatally[17,18].

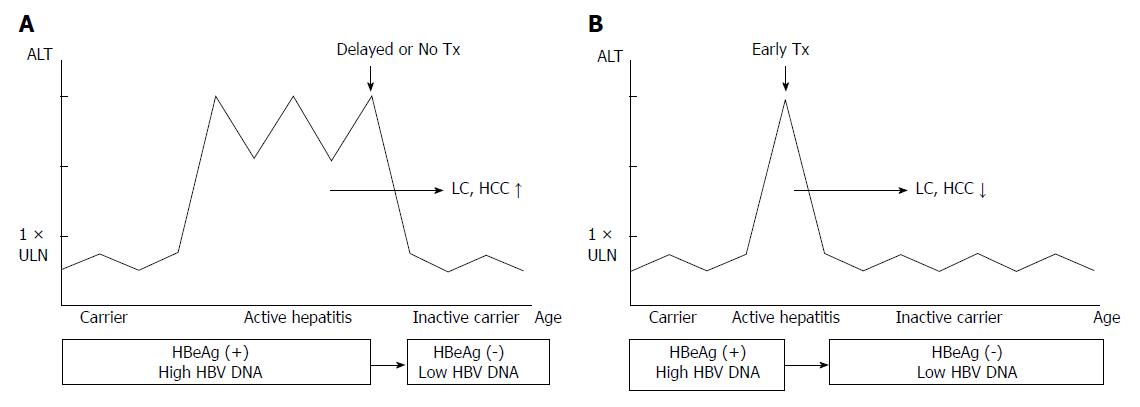

Although HBeAg seroconversion during treatment is the primary therapeutic target, spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion occurs through the immune clearance phase, after necroinflammation of the liver and subsequent removal of infected hepatocytes. It is during this phase that the plausibility of liver complications may increase, according to the severity and duration of active hepatitis. Even normalization of ALT and disappearance of HBeAg would not guarantee the prevention of liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, had it been untreated or neglected after a series of inappropriate herbal remedies which may have deteriorated the disease for a prolonged period (Figure 1A). In general, spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion usually leads to good prognosis in adults; however, one third of active hepatitis (HBeAg positive or negative) may recur and some of these patients may even develop liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma[12]. A study of European children with horizontally transmitted chronic hepatitis B, with an average of 5.2 ± 4.0 years of follow up, showed that most of them lost HBeAg and had a good prognosis, but some made the transition to HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis or progressed into hepatocellular carcinoma[19].

Figure 1 Altered course of chronic hepatitis B according to timing of starting treatment (Tx).

A: Delayed or no treatment results in higher incidence of liver cirrhosis (LC) or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); B: Treatment in early immune-clearance phase results in lower incidence of LC or HCC. ALT should be higher than 2 times of upper limit of normal values (> 2 × ULN); HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

It is extremely rare for HBsAg to spontaneously disappear in South Korea unlike western countries where the major route of infection is through horizontal transmission. In Taiwan, a country where the majority of hepatitis B is transmitted vertically as in Korea, the spontaneous HBsAg loss rate is also very low, 0.56%, compared to western countries[20,21]. Korean reports also show that HBsAg spontaneously disappears only in 1.5% of patients under the age of nineteen[16].

MANAGEMENT OF CHILDHOOD CHRONIC HEPATITIS B CARRIERS

Most chronic hepatitis B patients are asymptomatic. Childhood chronic hepatitis B generally goes through the immune tolerance phase where ALT is normal and there is little or no inflammation in the liver tissue. This period persists for about 10-30 years but may also progress into the immune clearance phase in children[8]. In two follow up studies in Korea and Taiwan, spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion occurred in 11% and 24% of children under the age of 10, respectively[16,20]. In addition, these studies showed that 32% of those under the age of 19 turned HBeAg negative in South Korea[16].

Since spontaneous HbeAg seroconversion occurs at the end of the immune clearance phase, the long-lasting immune clearance phase could lead to the development of liver cirrhosis or even hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, early management to shorten the duration of active hepatitis (immune clearance phase) is important (Figure 1B). Monitoring ALT levels at intervals of at least six months is necessary to avoid patients going through unrecognized active hepatitis in their childhood, as well as to detect the earliest transition time to the immune clearance phase for patients in the immune tolerant phase. In a Korean study of children with chronic hepatitis B, the estimated rate of entry to the immune clearance phase was 4.6% for those under the age of 6, 7.1% for those between 6 and 12 years, and 28.0% for patients between 12 and 18 years, which was significantly higher than that observed for children under the age of 12[22].

If left untreated or treated inappropriately during the immune clearance phase, liver damage is unavoidable as it has already occurred and progressed, even though spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion has occurred, because the rate of HBeAg seroconversion is not significantly increased by long-term follow-up, treated or not[23]. The risk is known to increase proportionally with time until the point of HBeAg seroconversion[24-27].

DIAGNOSIS OF CHRONIC HEPATITIS B

Laboratory interpretation

Positive HBeAg does not mean active hepatitis in children. HBeAg is positive in both the immune tolerance phase and the immune clearance phase. Serum HBV DNA, ALT, and HBeAg titer are the parameters for distinguishing the two phases. Active hepatitis is defined when serum transaminase AST/ALT is persistently increased and serum HBV DNA level is over 107-1010 copies/mL, regardless of HBeAg status.

If the HBV DNA level is high despite negative HBeAg, it may indicate the possibility of HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis B by a precore mutant virus or core promoter mutation[28]. These types of hepatitis are also classified as active hepatitis B if they accompany high levels of serum ALT and serum HBV DNA over 104-108 copies/mL, and also need active treatment[29]. It is not prevalent but not negligible during childhood years and needs special attention during treatment and monitoring[28]. Quantitative serum HBV DNA tests are especially important so as to analyze viral response (VR), for it is impossible to assay the level of viral replication with HBeAg alone in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis patients.

Liver biopsy

Liver biopsy is imperative for assessing the necroinflammatory grade and fibrosis stage of liver damage, and helps as a guide for making treatment decisions[30]. However, histological assessment is not essential for the initiation of treatment, especially in children[31].

Biopsy results are usually near normal in HBV carrier children; however, that does not mean that they are always normal. Most liver biopsy samples from children with chronic hepatitis B show minor inflammation and fibrosis; nevertheless, cases exist with severity up to liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma[32]. An HBV carrier whose ALT level has been normal since they were young would be in the immune tolerance phase and the liver tissue would be favorable without significant necroinflammation or fibrosis[33]. However, prognosis and liver status would be different from those of HBeAg negative carriers in the low or nonreplicative phase who have gone through active hepatitis. Histology of the liver in the nonreplicative phase may vary from minimal necroinflammation and fibrosis to liver cirrhosis depending on the period and severity of liver damage during the immune clearance phase. The fact that even HBeAg positive healthy carriers show signs of chronic hepatitis in 40% of cases indicates that the majority of Korean adult carriers go through chronic active hepatitis B without realizing it[34]. These findings are similar to those studied in western countries, where extended fibrosis and even liver cirrhosis have been found in more than half of liver biopsy samples of children (ages 1-19, mean age 9.8 years) with HBeAg positivity and increased ALT[35].

As a non-invasive alternative test to liver biopsy, liver stiffness measurement (Fibroscan®) is frequently used for the evaluation of liver fibrosis, which is valuable in fibrosis staging in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B[36].

OPTIMAL TIMING OF STARTING TREATMENT OF CHRONIC HEPATITIS B

While most children with chronic hepatitis B remain asymptomatic, it may progress into liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma if left untreated during the immune clearance phase. A keen attention should be paid to the fact that a predominant portion of patients with chronic hepatitis B that progress into liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma get infected during the childhood period. Therefore, persistent follow up should be mandatory in order not to miss the appropriate period for treatment. Active treatment should be considered with the onset of the immune clearance phase.

Wait and see

Treatment is not needed for children with normal ALT for it is not active hepatitis, although there are very high serum HBV levels along with positive HBeAg. HBeAg positivity does not indicate active hepatitis during the immune tolerance phase. Treatment during this period does not ameliorate near-normal liver tissues nor does it bring elimination of HBeAg. On the other hand, such unnecessary treatment would bring tolerance to the medication and may lead to treatment failure in the future when active hepatitis may flare. Treatment is therefore not given to HBV carriers with normal AST/ALT values in children[8].

Consider treatment

Treatment should be considered, but not initiated immediately when HBeAg is positive and HBV DNA and ALT begin to increase. Treatment is considered in patients who have had serological evidence of HBV infection for at least 6 mo: that is, when HBsAg, HBeAg, HBV DNA are positive and ALT is consistently elevated; this would be regarded as the immune clearance phase of chronic hepatitis B which is appropriate for the initiation of treatment.

Special caution is needed before starting treatment immediately for HBV carriers with elevated liver enzymes. ALT elevation may not be due to chronic hepatitis B, but rather due to other systematic infections such as respiratory tract infection and urinary tract infection in infants and toddlers[8]. Moreover, as obesity is becoming a social problem nowadays, there is an increasing number of obese children and adolescents who may also have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Weight monitoring should be the priority in this case, and if ALT does not normalize after weight reduction, liver biopsy should be done to determine whether the severity of liver damage is associated with hepatitis B or NAFLD. HBV carriers with concomitant Wilson’s disease or muscular dystrophy are some of the other plausible reasons that may account for high levels of ALT, and need to be included in the differential diagnosis in children.

Even with the apparent increase in ALT, starting treatment at less than twice the level of the upper limit of ALT may lead to a higher chance of drug resistance, which could result in higher treatment failure[37].

Good predictor of treatment

Therapeutic response is better when serum ALT is high and HBV DNA low; that does not mean initiation of treatment should be left until this stage. Optimal treatment time should not be delayed until the end of the immune clearance phase when serum ALT is high and HBV DNA low, overlapping the period of HBeAg seroconversion. If left untreated until this period, the HBeAg seroconversion rate may increase by initiation of treatment at this moment because of the additional effect of spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion; however, it would bring the consequence of neglecting the chance to treat at the optimal time during the early immune clearance phase. Our ultimate goal does not lie in HBeAg seroconversion only. It lies in halting the replication of HBV, normalizing ALT and stopping the progression to liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma so as to reduce complications and mortality before the liver damage becomes irreversible[38]. The immune clearance phase is when liver tissue necrosis results in fibrosis by active inflammation, the severity and prolonged length relates to higher rates of complications such as liver cirrhosis (Figure 1). Children and adolescents are of no exception.

Delayed treatment and liver complication

Complications of chronic hepatitis B (liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma) can develop even in teenage carriers. It is known that the longer the immune clearance phase and the more frequently the ALT flare-up occurs, the more likely liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma is to occur. If active hepatitis is left untreated during the immune clearance phase, there is no guarantee that it will not progress into liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma even if spontaneous seroconversion of HBeAg or HBsAg occurs[18,19].

Progression rate into liver cirrhosis in HBeAg positive patients is known to be related to the length of HBeAg positive period and the reactivation rate of hepatitis[27]. If the serum HBV DNA level is persistently over 104 copies/mL, it then becomes a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma[39]. Therefore, the longer the immune tolerance phase and the immune clearance, the more likely complications may occur from chronic hepatitis; and of the two, the immune clearance phase plays a key role. In the natural course of chronic hepatitis B, it may seem as if the severity of liver complications increases from the point where HBeAg is lost. However, when HBeAg is lost during the initial phase of the immune clearance phase, it leads to a decrease of the HBeAg positive period and high HBV load period, meaning a reduction in liver complications as well. Meanwhile, it is necessary at all costs to check serum HBV DNA after the loss of HBeAg to confirm whether or not it is HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis.

TREATING CHRONIC HEPATITIS B WITH NUCLEOS(T)IDE ANALOGUE

The therapeutic efficacy of IFN-alpha in a multinational randomized controlled study was 33% at 48 wk after the initiation of 24 wk of treatment for children[40]. IFN therapy may have more chance of cure in the aspect of HBsAg clearance, especially in younger children < 5 years of age[41]. Currently, clinical trials are undergoing in children using pegylated interferon-α alone or combined with nucleos(t)ide analogue which may have promising results, especially in Western countries.

The predominant genotypes of HBV are B and C in China and South East Asian countries[23]. In adult studies, the therapeutic response to IFN was better for genotype B than C[42]. However, IFN is not very effective in genotype C predominant regions, where most children are vertically infected[43,44]. Children treated with lamivudine showed a significantly higher HBeAg and HBsAg seroconversion rate compared to IFN-treated children in a long-term follow-up study in Korea, where genotype C was predominant[45].

Antiviral resistance

Drug resistance increases with the prolonged use of the nucleos(t)ide analogues. The resistance rate seen in children after two years is 23%[45]. Liver function may deteriorate after antiviral resistance to medication due to the YMDD mutation and may require substitution of the drug. A successful therapeutic response could be achieved when HBeAg seroconversion occurs before the advent of drug tolerance.

At present, entecavir and tenofovir are registered for use in children over 16 years and 12 years, respectively, though they are the first-line anti-viral agents according to most HBV treatment guidelines. In children, more effective virologic responses have been demonstrated with the use of either add-on adefovir or switching to entecavir monotherapy compared with those with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B who switched to adefovir monotherapy[46]. However, resistance to lamivudine is a risk factor for entecavir resistance and adefovir is no longer the first line option.

How long to use

The nucleos(t)ide analogue is not a drug that should be stopped after a certain period of time, but rather a medication to be continued until HBeAg seroconversion occurs. If stopped prior to seroconversion, hepatitis is most likely to reactivate. The therapeutic goals for antiviral treatment in HBeAg positive patients are as follows: undetected HBV DNA in PCR (< 103 copies/mL), normalized serum ALT, at least one year of undetected HBeAg before discontinuing the medication, and persistence of anti-HBe[47,48]. HBV DNA suppression has a close correlation with recovery of liver tissues and HBeAg seroconversion[49].

It is true that up to 10% of infected hepatocytes may survive after one year of treatment with lamivudine since lamivudine does not affect the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) of HBV inside the nucleus of hepatocytes[50]. HBV DNA will decrease, however, to the level where it would be impossible for HBV DNA to be resistant to antiviral agents, if treated and suppressed for a sufficient period. Complete viral eradication means removal of remaining cccDNA from the hepatocyte, and this is made possible by the normal turnover of hepatocytes and reactivation of the host immune response[28]. This supports the 2011 KASL and 2012 EASL guidelines for continuing the nucleos(t)ide analogue for one year or more after disappearance of HBeAg[48,51].

Special caution is needed in HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis patients when using the nucleos(t)ide analogue so that the medication is not halted shortly after HBV DNA clearance. HBeAg/anti-HBe seroconversion cannot be effectively measured in HbeAg negative patients for anti-HBe positivity from the initial time point. In my opinion, at least two or three additional years of antiviral treatment is required for such children after the occurrence of HBV DNA clearance[52].

HBsAg clearance

In adults, treatment of hepatitis rarely results in a loss of HBsAg, which is the ultimate goal of treating chronic hepatitis B. However, in a study conducted by Choe et al[45], loss of HBsAg occurred in 42% in patients of preschool age after two years of lamivudine treatment. HBsAg disappeared in 13 of the 49 (26.5%) patients who experienced lamivudine-induced HBeAg seroconversion[53]. However, HBsAg loss in school children rarely occurred, similar to those in adults.

PREVENTION OF NUCLEOS(T)IDE ANALOGUE RESISTANCE

Pretreatment baseline ALT > 2 × ULN

The resistance rates to lamivudine were reported in children (pretreatment baseline ALT > 2 × ULN) to be 10% at 1 year of treatment and 23%-26% at 2 years after the initiation of treatment[37,45]. Breakthrough was only seen in 5.9% of the 2-year treatment group in preschool children with higher pretreatment baseline ALT[37]. Similar results have been shown by other studies in Korean children[54,55]. The results in children are lower than those in adult studies[56,57].

On the other hand, in a western multicenter study, antiviral resistance analysis showed that the YMDD mutation rate was as high as 49% in 2-year treatment and 64% in 3-year treatment, in that order[58]. These outcomes were even worse than those of adults.

That study included an inappropriate portion of patients with active hepatitis. Only 51% and 11% of children with pretreatment ALT > 2 × ULN were enrolled for the 2 and 3-year treatment groups, respectively. Enrolling significant numbers of patients with a pretreatment ALT level < 2 × ULN explains such a high resistance rate in western children. Therefore, an elevated pretreatment ALT level (> 2 × ULN) is key to decreasing antiviral resistance.

Confirm the immune clearance phase

Primary treatment with the nucleos(t)ide analogue should be considered if patients have persistently elevated ALT levels > 2 × ULN for more than 6 mo, nonetheless it should be confirmed that patients are in the immune clearance phase. Prior to starting therapy, a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s status is important to exclude other causes of abnormal liver function tests, such as reactive hepatitis in infants and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obese children.

Compliance

One of the most important predictive factors for the therapeutic response to the nucleos(t)ide analogue is good compliance[59]. A significant portion of viral breakthrough is due to poor adherence to the medication[60]. Education of children and their parents (guardian) is required to continue good compliance leading to ideal therapeutic outcome, based on trust between doctors and patients. In addition, the optimal dosage according to body weight should be adjusted by the clinicians as children grow rapidly.

On treatment monitoring and keep up-to-date by the most current guidelines

Treatment response at 24 wk is important to take which treatment strategy to use. Patients with a complete virologic response generally have a very low possibility of antiviral resistance[61].

Proper monitoring for virologic breakthrough is needed, because early detection is critical to decide the most ideal intervention. If the nucleos(t)ide analogue is stopped before or immediately after HBeAg seroconversion, the likelihood of recurrence increases. Therefore, the 2011 KASL (Korean Association for Study of Liver) guidelines and 2012 EASL guidelines advise continuing the nucleos(t)ide analogue for one year or more after the disappearance of HBeAg to sustain a serological and/or virological response[48,51].

CONCLUSION

In most children with chronic hepatitis B, treatment indications should be very carefully evaluated. Treatment should concentrate on suppressing viral replication in the early period of immune active hepatitis. High potent nucleos(t)ide analogues such as tenofovir and entecavir are anticipated to be available for use in younger children, which also have a high genetic barrier.

P- Reviewer: Marignani M S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Zhang DN