Published online Mar 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3356

Revised: January 29, 2014

Accepted: March 4, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2014

Processing time: 115 Days and 5.9 Hours

AIM: To determine the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer in clinical practice, a retrospective analysis was conducted in a high-volume Chinese cancer center.

METHODS: Between November 1995 and June 2007, a total of 423 gastric or esophagogastric adenocarcinoma patients who did (Arm A, n = 300) or did not (Arm S, n = 123) receive radical gastrectomy followed by postoperative chemotherapy were enrolled in this retrospective analysis. In Arm A, monotherapy(fluoropyrimidines, n = 25), doublet (platinum/fluoropyrimidines, n = 164), or triplet regimens [docetaxel/cisplatin/5FU (DCF), or modified DCF, epirubicin/cisplatin/5FU (ECF) or modified ECF, etoposide/cisplatin/FU, n = 111] were administered. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were compared between the two arms. A subgroup analysis was carried out in Arm A. A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors was conducted.

RESULTS: Stage I, II and III cancers accounted for 9.7%, 35.7% and 54.6% of the cases, respectively, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, 7th edition. Only 178 (42.1%) patients had more than 15 lymph nodes harvested. Hazard ratio estimates for Arm A compared with Arm S were 0.47 (P < 0.001) for OS and 0.59 (P < 0.001) for DFS. The 5-year OS rate was 52% in Arm A vs 36% in Arm S (P = 0.01); the adverse events in Arm A were mild and easily controlled. Ultimately, 73 patients (26.5%) who received doublet or triplet regimens switched to monotherapy with fluoropyrimidines. The OS and DFS did not differ between monotherapy and the combination regimens, however, both were statistically improved in the subgroup of patients who were switched to monotherapy with fluoropyrimidines after doublet or triplet regimens as well as patients who received ≥ 8 cycles of chemotherapy.

CONCLUSION: In clinical practice, platinum/fluoropyrimidines with adequate treatment duration is recommended for stage II/III gastric cancer patients accordingto the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system after curative gastrectomyeven with limited lymphadenectomy.

Core tip: Although the ACTS GC and CLASSIC trials demonstrated that postoperative chemotherapy improved overall survival after standard D2 gastrectomy, severe challenges in adjuvant settings remain unsettled, such as low D2 resection rates in some regions. Our retrospective study is complementary to large-scale phase III prospective trials, and demonstrated the efficacy and safety of postoperative platinum/fluoropyrimidines in stage II/III gastric cancer patients accordingto the updated 7th edition staging system after curative gastrectomy with standard or limited lymphadenectomy.

- Citation: Deng W, Wang QW, Zhang XT, Lu M, Li J, Li Y, Gong JF, Zhou J, Lu ZH, Shen L. Retrospective analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for curatively resected gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(12): 3356-3363

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i12/3356.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3356

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourthmost common type of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. It is also the second most frequent malignancy in China[2]. More patients are diagnosed with late stage GC in China than in South Korea and Japan, with up to 60% of patients in stage III according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system[3,4].

Surgical resection of the primary tumor and regional lymph node dissection is the mainstay of curative treatment for patients with locally advanced GC (LAGC). Different types of surgical procedures for GC can affect the results of postoperative chemotherapy. Gastrectomy with extended (D2) lymphnode dissection is considered standard treatment in both Asian and Western countries[5]. However, in clinical practice, D2 lymphadenectomy rates vary among different hospitals and regions in China. In some European and American countries such as Turkey and Chile, high incidence rates, high rates of late-stage GC, and deficiencies in specially trained surgeons are considered to be severely challenging as in China[1].

Globally, adjuvant treatment varies among countries, based on data from different clinical studies. The Intergroup-0116 study and the MAGIC study showed that postoperative chemoradiotherapy or perioperative chemotherapy improved overall survival compared with surgery alone[6,7]. However, both studies assessed the benefits of adjuvant therapy after only limited surgery, which has long been questioned by Asian oncologists. Recently, two large-scale randomized phase III trials (the ACTS GC study and the CLASSIC study) demonstrated that postoperative chemotherapy increased the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate by 13%-15% after standard D2 gastrectomy[8,9]. However, significant challenges in adjuvant therapy remained unsettled, such as low D2-resection rates in many regions. Moreover, it is unclear whether the Japanese regimen with TS1 for 1 year or the Korean regimen with oxaliplatin/capecitabine (XELOX) for 8 cycles was more effective and better tolerated. To date, no direct comparison has been carried out in prospective studies, and oncologists are uncertain about which regimen to choose. In addition, the AJCC staging system was updated from the 6th to the 7th edition in 2010, but neither of the above-mentioned trials enrolled sufficient patients with pathological grade T4 or N3 tumors. These patients were classified as stage IV under the 6th version, but were classified as stage II-IIIC under the 7th version[10,11]. Thus, no evidence is available to guide adjuvant treatment in this population. It is clear that the data from the prospective ACTS GC and CLASSIC studies do not fully meet the needs in clinical practice, even in Japan and South Korea.

Thus, in this 12-year retrospective study, we assessed the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in LAGC patients classified according to the 7th edition of the AJCC system after curative gastrectomy with limited or standard lymphadenectomy.

Between November 1995 and June 2007, 423 consecutive LAGC patients treated with surgery alone or with surgery followed by post-operative chemotherapy were enrolled in this study. The surgeries had been conducted by surgical oncologists or general surgeons in 62 different Chinese institutes ranging from specialized cancer centers to general hospitals, while the consultations or adjuvant chemotherapy had been carried out in a single center at the Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute. The inclusion criteria were as follows: histologically confirmed gastric adenocarcinoma; curative resection with at least D1 lymphadenectomy; no evidence of distant metastases; TNM stage of IB-IIIC (according to the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system); no previous malignancies; and no neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy prior to surgery. The exclusion criteria were as follows: incomplete medical records or refusal to follow-up.

Of the 423 enrolled patients, 123 received surgery alone (surgery-alone arm, Arm S) and 300 received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy (adjuvant arm, Arm A). The chemotherapeutic regimens were as follows: monotherapy with fluoropyrimidines (capecitabine, TS-1, tegafur-uracil, infusional 5FU), doublet regimens (cisplatin with a fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin with a fluoropyrimidine), or triplet regimens (eitherpaclitaxel, docetaxel, epirubicin or etoposide with cisplatin or oxaliplatin and a fluoropyrimidine). No patient received radiotherapy. Regimen selection was based on stage, performance status, available combinations and patient preferences. Triplet regimens were considered for patients with T3/T4 tumors and positive lymph nodes; doublet regimens were considered for patients with T3/T4 tumors or positive lymph nodes. Etoposide was administered prior to 2003, and taxanes were administered after 2003. Monotherapy was considered for patients with poor performance status or co-morbidities or elderly patients.

Patients in Arm A underwent hematologic testing and assessment of their clinical symptoms each week at Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute. Patients in Arm S underwent examinations at local hospitals, and the results of their hematologic tests or symptom records were not complete. Adverse events were defined according to the Common Toxicity Criteria of the National Cancer Institute, version 3.0. The presence of a relapse was determined by means of imaging studies or pathological diagnosis, including ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), gastrointestinal radiography series, or endoscopy. For suspected disease, additional diagnostic tools were considered. Patients underwent at least one type of imaging study, usually CT, at 3-mo intervals during the first 2 years after surgery and at 6-mointervals thereafter until 5 years after surgery.

The data were processed using SPSS version 15.0 for Windows XP. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time from surgery prior to a recurrence of gastric cancer, the occurrence of a second primary cancer, or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from surgery to death from any cause. Univariate analyses were applied to evaluate the prognostic factors affecting the survival rate in patients with various histopathologic characteristics and adjuvant therapy regimens. Each categorical variable was compared using the chi-squared test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis. The Log-rank rule was applied in the monovariate analyses, while a Cox proportional hazard regression model was used in the multivariate analysis. A P value of less than 0.5 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 423 patients were enrolled in this study: 300 in Arm A and 123 in Arm S. In these patients, stage I, II and III GC accounted for 9.7%, 35.7% and 54.6%, respectively. As the surgeries had been carried out at various Chinese hospitals and no photographs were collected, the details of the procedures were difficult to qualify,however, 178 (42.1%) patients had more than 15 lymph nodes harvested.

The patient profile and tumor characteristics, except for age, were well balanced between Arm A and Arm S (Table 1). More elderly patients (≥ 65 years old) were included in Arm S (43.9%) than in Arm A (29.3%, P = 0.04). In addition, Arm S patients tended to have earlier-stage GC than Arm A patients (18.7% stage IB in Arm S vs 6.0% in Arm A, P = 0.12), and the rate of having a ratio of positive lymph nodes harvested < 0.33 was 66.7% in Arm S and 57.7% in Arm A (P = 0.07).

| Characteristics | Total | Arm A | Arm S | Pvalue |

| Number | 423 | 300 (70.9) | 123 (29.1) | NA |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 320 (75.7) | 223 (74.3) | 97 (78.9) | 0.324 |

| Female | 103 (24.3) | 77 (25.7) | 26 (21.1) | |

| Age group | ||||

| < 65 | 281 (66.4) | 212 (70.7) | 69 (56.1) | 0.04 |

| ≥ 65 | 142 (33.6) | 88 (29.3) | 54 (43.9) | |

| Histology (adenocarcinoma) | ||||

| Well-moderate differentiated | 97 (22.9) | 61 (20.3) | 36 (29.2) | 0.145 |

| Poorly differentiated | 287 (67.8) | 211 (70.3) | 76 (61.8) | |

| Signet-ring cell | 24 (5.7) | 18 (6.1) | 6 (4.9) | |

| Mucinous | 15 (3.5) | 10 (3.3) | 5 (4.1) | |

| Location of tumor | ||||

| Proximal | 147 (34.8) | 95 (31.7) | 52 (42.3) | 0.07 |

| Distal | 276 (65.2) | 205 (68.3) | 71 (57.7) | |

| Extent of LN dissection | ||||

| < 15 | 202 (47.8) | 136 (45.3) | 66 (53.7) | 0.12 |

| ≥ 15 | 221 (52.2) | 164 (54.7) | 57 (46.3) | |

| Depth of invasion (T stage) | ||||

| T1 | 9 (2.1) | 7 (2.3) | 2 (1.6) | |

| T2 | 67 (15.8) | 35 (11.7) | 32 (26.0) | |

| T3 | 204 (48.2) | 165 (55.0) | 39 (31.7) | 0.529 |

| T4a | 89 (21.0) | 52 (17.3) | 37 (30.1) | |

| T4b | 54 (12.8) | 41 (13.7) | 13 (10.6) | |

| No. of invaded LN (N stage) | ||||

| N0 (0) | 117 (27.7) | 70 (23.3) | 47 (38.2) | 0.11 |

| N1 (1-2) | 126 (29.8) | 100 (33.3) | 26 (21.1) | |

| N2 (3-6) | 95 (22.5) | 68 (22.7) | 27 (22.0) | |

| N3 (≥ 7) | 85 (20.1) | 62 (20.7) | 23 (18.7) | |

| AJCC stage (7.0 version) | ||||

| IB | 41 (9.7) | 18 (6.0) | 23 (18.7) | 0.12 |

| IIA | 100 (23.6) | 70 (23.3) | 30 (24.4) | |

| IIB | 51 (12.1) | 38 (12.7) | 13 (10.6) | |

| IIIA | 56 (13.2) | 48 (16.0) | 8 (6.5) | |

| IIIB | 98 (23.2) | 67 (22.3) | 31 (25.2) | |

| IIIC | 77 (18.2) | 59 (19.7) | 18 (14.6) | |

| Positive/harvested LN ratio | ||||

| < 0.33 | 253 (59.8) | 171 (57.0) | 82 (66.7) | 0.07 |

| ≥ 0.33 | 170 (40.2) | 129 (43.0) | 41 (33.3) | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| Positive | 167 (39.5) | 115 (38.3) | 52 (42.3) | 0.542 |

| Negative | 130 (30.7) | 91 (30.3) | 39 (31.7) | |

| Unknown | 126 (29.8) | 94 (31.4) | 32 (26.0) |

Only the data for the 300 patients in Arm A were analyzed for adverse events, and the 123 patients in Arm S were not included in the safety analysis. Adverse events, including hematologic and non-hematologic toxic effects, were analyzed, and included leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated total serum bilirubin levels, peripheral neuropathy, nausea, and vomiting. The most frequent grade 3 or 4 adverse events were neutropenia (17.6%), nausea and vomiting (6.1%), anorexia (3.5%), and diarrhea (2.3%). In general, 61 patients (20.3%) developed grade 3 or 4 toxicities (data not shown).

Among the 300 patients in Arm A, the number of chemotherapy cycles ranged from 1 to 17 with a median of 6. Treatment was continued for at least 3 cycles in 269 patients (90.0%), at least 6 cycles in 176 patients (58.7%), at least 8 cycles in 79 patients (26.3%), and at least 10 cycles in 39 patients (13.0%). Reasons for withdrawal of treatment included refusal by the patient to continue treatment due to adverse events or other factors, the detection of metastasis or relapse. A total of 141 patients (47.0%) had dose modifications or chemotherapy delays. Of the 275 patients receiving doublet or triplet regimens, 73 patients (26.5%) switched to monotherapy due to toxicity or upon their request.

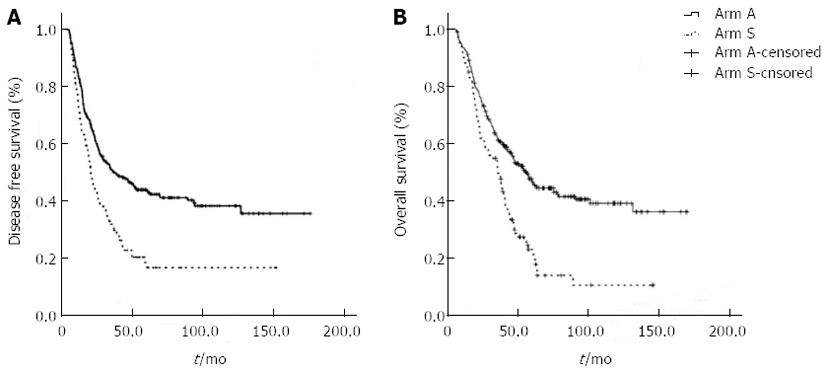

By the last follow-up examination on May 1st 2010, 283 patients (66.9%) were confirmed to have recurrent disease,and 238 patients (56.3%) had died; only 6 patients (1.4%) were lost of follow-up. The median OS and DFS based on a median follow-up time of 87.0 mo were 56.2 (95%CI: 48.4-64.0) and 33.4 (95%CI: 25.3-41.5)mo, respectively. The 5-year survival rate was 48.0%. Both median OS and DFS were statistically longer in Arm A than in Arm S: the OS was 63.0 mo (95%CI: 46.7-79.3) vs 42.9 mo (95%CI: 37.4-48.3) (P = 0.001), respectively; the 5-year OS was 52% vs 36%, respectively (P = 0.01); and the DFS was 41.5 mo (95%CI: 24.4-58.6) vs 24.4 mo (95%CI: 15.7-33.1), respectively (P = 0.007) (Figure 1). For stage II/III patients, a similar survival benefit was observed in Arm A. In Arm A vs Arm S, the OS was 58.0 mo (95%CI: 48.4-67.6) vs 37.6 mo (95%CI: 30.3-44.9), respectively (P < 0.001); the 5-year OS was 52% vs 36%, respectively (P = 0.01); the DFS was 34.9 mo (95%CI: 22.2-47.6) vs 14.9 mo (95%CI: 16.0-22.0), respectively (P < 0.001). The 5-year DFS was 45% in the chemotherapy group and 28% in the surgery-alone group (P = 0.07).

Among the 45 patients over 65 years old, no benefit in OS was observed in Arm A (n = 32) compared with Arm S (n = 13). The DFS tended toward improvement with chemotherapy at 49.4 mo in Arm A (95%CI: 35.7-63.1)vs 29.8 mo in Arm S (95%CI: 24.0-35.6, P = 0.053). In each of the following subgroup analyses, an initial comparison was performed for patients over 65 to exclude potential bias due to age.

Patients in Arm A received monotherapy (n = 25) or doublet (n = 164) or triplet (n = 111) regimens as postoperative chemotherapy. The OS was shorter in the monotherapy group (46.6 mo, 95%CI: 25.6-67.6) than in the doublet (63.2 mo, 95%CI: 22.9-103.5) or triplet (65.2 mo, 95%CI: 43.4-86.9)therapy groups, but the difference was not statistically significant. The DFS showed the same tendency for the monotherapy, doublet and triplet therapy groups at 24.5 mo (95%CI: 8.2-40.8), 38.4 mo (95%CI: 20.0-80.3) and 45.8 mo (95%CI: 19.2-72.4), respectively (P = 0.321).

In the doublet regimen group (n = 164), 124 patients (75.6%) received oxaliplatin/fluoropyrimidines, and 40 patients (24.4%) received cisplatin/fluoropyrimidines; no differences in OS or DFS were detected between the two subgroups (data not shown). In the triplet regimen group (n = 111), 24 patients (21.6%) received DCF or modified DCF (taxanes/cisplatin/5FU), 52 patients (46.8%) received epirubicin/cisplatin/5FU (ECF) or modified ECF (epirubicin with cisplatin or oxaliplatin and 5FU or capecitabine), and 35 patients (31.5%) received etoposide/cisplatin/5FU. No differences in DFS or OS were observed among the three subgroups (data not shown). In Arm A, a total of 272 (90.7%) patients received platinum/fluoropyrimidine-containing regimens which included either oxaliplatin (n = 126) or cisplatin (n = 146), and no survival differences were observed (data not shown).

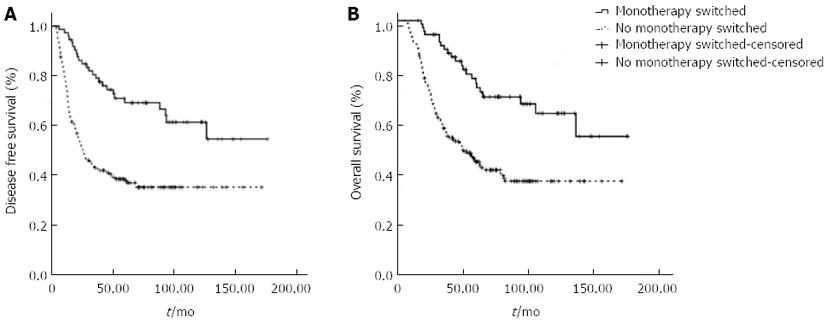

Among patients who received doublet or triplet regimens, 73 patients (26.5%) switched to monotherapy with fluoropyrimidines, either oral or infused. Significant differences in the total number of chemotherapy cycles, OS and DFS were observed between patients who switched and patients who did not (Table 2, Figure 2). Regimens modified to monotherapy with fluoropyrimidines significantly prolonged OS and DFS in both the doublet and triplet regimen groups.

| n | Cycles median (range) | Disease-free survival (mo) (95%CI) | Overall survival (mo) (95%CI) | |

| Monotherapy | 25 | 4 (2-15) | ||

| Doublet | 164 | 6 (1-17) | 38.4 (21.0-80.3) | 63.2 (22.9-103.5)1 |

| Monotherapy switched | 38 | 8 (3-17) | NR1 | NR1 |

| No monotherapy switched | 126 | 6 (1-12) | 25.4 (18.7-32.1) | 44.4 (28.3-60.5) |

| Triplet | 111 | 6 (2-14) | 45.8 (19.2-72.4)1 | 65.2 (43.5-87.0)1 |

| Monotherapy switched | 35 | 9 (5-14) | NR1 | NR1 |

| No monotherapy switched | 76 | 6 (2-11) | 24.9 (9.4-40.4) | 56.2 (42.0-70.4) |

| Doublet and triplet | 275 | 6 (1-17) | 45.8 (23.8-67.8) | 63.8 (41.4-86.2) |

| Monotherapy switched | 73 | 8 (3-17) | NR1 | NR1 |

| No monotherapy switched | 202 | 6 (1-12) | 25.4 (18.3-32.5) | 49.4 (35.7-63.1) |

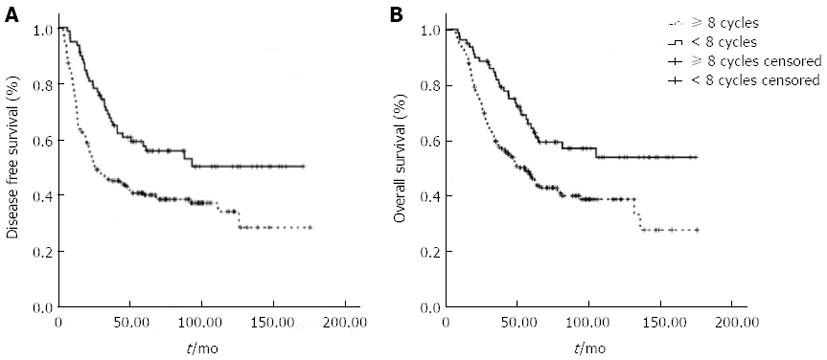

Given that switching to monotherapy could have improved the treatment tolerability and prolonged duration of the chemotherapy, we further compared survival data of patients who received ≥ 8 chemotherapy cycles within 8 mo after surgery with patients who received ≤ 7 chemotherapy cycles in the same time period (Figure 3). Statistically longer OS and DFS rates were observed in the group with ≥ 8 chemotherapy cycles (P < 0.001), indicating that a longer adjuvant duration provided a survival benefit in patients who switched to monotherapy.

Univariate analysis showed an association between OS and DFS and location of the tumor (P = 0.014), T stage (P < 0.001), N stage (P < 0.001), positive/harvested lymph node (LN) ratio (P < 0.001), and adjuvant chemotherapy treatment (P = 0.001). Similarly, LN dissection was a significant factor for DFS (P = 0.032) (data not shown). In contrast, gender, age, WHO performance status and histological differentiation did not affect the OS or DFS.

On multivariate analysis, the extension of the LN dissection (< 15 and ≥ 15 LNs harvested), N stage and adjuvant chemotherapy were associated with OS and DFS, whereas the location of the tumor and T stage were independent factors for DFS. Therefore, the multivariate analysis using a Cox regression identified 3 prognostic factors: the extension of the LN dissection (P = 0.008), the N stage (P = 0.012), and treatment with postoperative chemotherapy (P < 0.001). After adjustment, the Cox hazard ratio (HR) estimation for Arm A compared with Arm S was 0.47 (95%CI: 0.36-0.63; P < 0.001) for the OS and 0.59 (95%CI: 0.44-0.79; P < 0.001) for the DFS (data not shown), indicating a risk reduction in patients who received adjuvant therapy.

Adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection is known to improve outcomes in gastric cancer treatment, although the preferred recommendations differ by geographical region[12]. Based on the United States Intergroup-0116, United Kingdom MAGIC, Japan ACTS GC, and South Korea CLASSIC studies, the recommended adjuvant treatments are chemoradiotherapy in the United States, perioperative chemotherapy in the United Kingdom and a few other European countries, and adjuvant chemotherapy in most Asian countries, either TS1 for 1 year or XELOX for 8 cycles over 6 mo[6-9]. The former two studies enrolled patients who underwent only limited surgeries, while the latter two studies enrolled patients who underwent at least D2 gastrectomy.

It is well accepted that the type of surgical procedure will affect the results of adjuvant treatment[13]. D2 gastrectomy is now recommended as the standard surgical treatment for resectable GC in both Asian and Western countries[14-17]. However, D2 lymphadenectomy is a demanding technique, requiring rigorous training and a sufficient number of annual operations to ensure the skill of the surgeons. Unlike Japan and South Korea, many institutions in rural areas or small cities in China are not specialized centers with appropriate surgical expertise and postoperative care. In 2010, out of 2312 consecutive GC patients who underwent resection in a high-volume cancer center, more than 14 lymph nodes were harvested in only 650 (28.1%)[18]. Additionally, although D2 lymphadenectomy has become more widespread recently in China due to continuing education, the exact proportion of D2 lymphadenectomies throughout the country is not yet available. In this study, it was difficult to establish the details of the surgical procedures at other institutions. We were only able to qualify the surgeries by the number of lymph nodes harvested based on the classification of the NCCN guidelines in which dissecting a minimum of 15 lymph nodes for histologic examination is required for both D1 and modified D2 resections[15].

In addition, T4/N3 patients classified according to the 6th edition of the AJCC staging system are now classified as stage II-IIIC in the updated 7th edition. Although they lacked distant metastasis, these patients were previously regarded as stage IV and thus were not enrolled in clinical studies of adjuvant therapies such as the ACTS GC and CLASSIC studies. However, these so-called “stage IV-M0” patients comprise a significant fraction of the patients in China. Therefore, these two large-scale phase III studies are still far from solving the known challenges in clinical practice such as non-ideal surgeries and more patients at later stages. We hope that this retrospective study which conducted analyses using the definitions of the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system will provide complementary data for oncologists not only in China, but also in nations where D2 lymphadenectomy is limited to some extent. Patients were consecutively enrolled at a single center, but they were drawn from throughout China for consultation or treatment. Thus, the findings should be applicable to clinical practice nationwide.

Age was not well balanced between the two arms of surgery alone and surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy, with more elderly patients in Arm S. However, in the subgroup of patients over 65 years of age (n = 45), no differences in the OS or DFS were observed between Arm S and Arm A. It is unlikely that the age imbalance influenced the results of the overall analysis. Patients in Arm S tended to be at earlier pathological stages, although this trend was not statistically significant. In general clinical practice, oncologists are less likely to prescribe chemotherapy for older patients or patients at relatively earlier stages because requests from patients and their families would interfere with the doctors’ decisions under such circumstances.

In general, adjuvant chemotherapy in this 12-year retrospective study was safe and effective in prolonging the 5-year OS and DFS. Following the exclusion of stage I patients, the survival benefit remained significant in stage II/III patients according to the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system. This benefit was also confirmed on multivariate analysis, which showed a risk reduction in patients who received adjuvant therapy. Currently, no further data on adjuvant chemotherapy in prospective studies using the 7th edition of the AJCC staging system are available. Based on this study, it is reasonable to deduce that patients classified as stage II/III under the new staging system are also likely to benefit from postoperative chemotherapy.

Surprisingly, no significant difference in survival was found among monotherapy and doublet and triplet regimens, while patients who switched to monotherapy or underwent ≥ 8 cycles of chemotherapy experienced prolonged DFS and OS by up to 2-fold. These results were consistent with the findings from the ACTS GC study in which the OS correlated with the duration of TS1 administration[19]. Considering that only 67% of the patients completed adjuvant chemotherapy in both the ACTS GC and CLASSIC studies, proper timing of treatment modification and an adequate duration of adjuvant treatment might be more effective in producing survival benefit than high-dose chemotherapy or combinations of stronger or more chemotherapeutic agents.

Subsequent to fluoropyrimidines and platinum, paclitaxel sequenced with oral fluoropyrimidines was tested in Yoshida’s large-scale randomized phase III study (the SAMIT trial), but it failed to show a survival benefit superior to monotherapy with oral fluoropyrimidines[20]. In our study, various chemotherapeutic agents, including taxane-, platinum-, epirubicin-, or etoposide-based regimens, did not show any significant differences in survival benefit. These results was supported by an inter-trial comparison between the ARTIST and CLASSIC studies[21]. After standard D2 gastrectomy, patients receiving 6 cycles of cisplatin/capecitabine, the control group in the ARTIST study, showed a 3-year DFS, which was similar to patients receiving 8 cycles of oxaliplatin/capecitabine in the CLASSIC study. Consequently, fluoropyrimidines with or without platinum (either cisplatin or oxaliplatin) is considered effective and safe as adjuvant therapy, even for patients who did not receive standard D2 lymphadenectomy. New agents such as taxanes and even trastuzumab for HER2-overexpressing tumors should be studied in future explorative trials based on molecular pathological classification systems or the efficacy of predictive biomarkers.

In conclusion, this retrospective study was complementary to large-scale phase III prospective trials which demonstrated the efficacy and safety of postoperative platinum with fluoropyrimidines in stage II/III gastric cancer patients under the updated 7th edition AJCC staging system after curative gastrectomy with standard or limited lymphadenectomy. Necessary treatment modifications and adequate treatment durations are recommended in adjuvant settings.

Adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection is known to improve outcomes in gastric cancer treatment, although the preferred recommendations differ by geographical region.

Recently, two large-scale randomized phase III trials demonstrated that postoperative chemotherapy increased the 5-year overall survival rate by 13%-15% after standard D2 gastrectomy. However, significant challenges in adjuvant therapy remained unsettled, such as low D2-resection rates in many regions.

In clinical practice, platinum/fluoropyrimidines with adequate treatment duration is recommended for stage II/III gastric cancer patients under the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system after curative gastrectomy with even limited lymphadenectomy.

Adjuvant chemotherapy in this 12-year retrospective study was safe and effective in prolonging the 5-year overall survival and disease-free survival.

It’s an interesting and well-presented retrospective study demonstrating the efficacy and safety of postoperative platinum/fluoropyrimidines.

P- Reviewers: Nedrebo BS, Rosell R S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893-2917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11128] [Cited by in RCA: 11831] [Article Influence: 845.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Parkin DM, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:33-64, 1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1285] [Cited by in RCA: 1255] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shan F, Li Z, Bu Z, Zhang L, Wu A, Wu X. The analysis of gastric cancer staging AJCC. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2011;8:675-680. |

| 4. | Shen D, Ni X, He C, Cao H, Shen Y. Comparison of value for predicting prognosis between 6th and 7th editions of TNM staging system in gastric cancer patients. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2012;9:536-539. |

| 5. | Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v50-v54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2465] [Cited by in RCA: 2435] [Article Influence: 101.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4899] [Cited by in RCA: 4592] [Article Influence: 241.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, Kinoshita T, Fujii M, Nashimoto A, Furukawa H, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y, Imamura H. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810-1820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 1941] [Article Influence: 107.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, Lee KW, Kim YH, Noh SI, Cho JY. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1290] [Article Influence: 99.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Greene FL. AJCC Cancer staging manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag 2002; 111-119. |

| 11. | Edge S, Byrd D, Compton C, Fritz A, Greene F, Trotti A. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag 2010; 117-126. |

| 12. | Paoletti X, Oba K, Burzykowski T, Michiels S, Ohashi Y, Pignon JP, Rougier P, Sakamoto J, Sargent D, Sasako M. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303:1729-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hundahl SA, Macdonald JS, Benedetti J, Fitzsimmons T. Surgical treatment variation in a prospective, randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy in gastric cancer: the effect of undertreatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:278-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1140] [Cited by in RCA: 1306] [Article Influence: 87.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Gastric Cancer. Version 2, 2011. Available from: http://www.nccn.org. |

| 16. | Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ministry of health. Gastric cancer treatment guideline 2011. Available from: http://www. moh.gov.cn/mohyzs/s3585/201103/50914.shtml. |

| 18. | Wu AW, Ji JF, Yang H, Li YN, Li SX, Zhang LH, Li ZY, Wu XJ, Zong XL, Bu ZD. Long-Term Outcome of A Large Series of Gastric Cancer Patients in China. Chin J Cancer Res. 2010;22:167-175. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shinichi S, Mitsuru S, Toshiharu Y, Taira K, Masashi F, Autsushi N, Hiroshi F, Toshifusa N, Yasuo O. Five-year follow up data of ACTS-GC study. The 83rd Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Meeting;. 2010;113. |

| 20. | Kazuhiro Y, Akira T, Michiya K, Shigefumi Y, Masazumi T, Nobuhiro T,SAMIT trial group. SAMIT: A phase III randomized clinical trial of adjuvant paclitaxel followed by oral fluorinated pyrimidines for locally advanced gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:Abstrt LBA4002. |

| 21. | Lee J, Lim do H, Kim S, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Choi MG, Sohn TS, Noh JH. Phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus cisplatin versus capecitabine plus cisplatin with concurrent capecitabine radiotherapy in completely resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: the ARTIST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |