Published online Mar 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3350

Revised: January 14, 2014

Accepted: February 26, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2014

Processing time: 154 Days and 11.7 Hours

AIM: To investigate the feasibility, efficacy and safety of laparoscopic hepaticoplasty using gallbladder as subcutaneous tunnel and sphincter-of-Oddi preservation for hepatolithiasis.

METHODS: From January 2010 to July 2013, six patients with hepatolithiasis were treated at our institution. All the patients underwent laparoscopic surgery. The procedures included common hepatic duct exploration, stone clearance by fiberoptic choledochoscopy, hilar bile duct hepaticoplasty with preservation of the sphincter of Oddi, anastomosis between the hilar bile duct and neck of the gallbladder, and establishment of a subcutaneous tunnel with the gallbladder. Two patients underwent left lateral hepatectomy simultaneously. Clinical data including operation time, intraoperative blood loss, operative morbidity, hospital mortality, stone clearance, and recurrence rate were analyzed.

RESULTS: All patients successfully completed laparoscopic surgery. The mean length of hospital stay was 4.5 ± 0.9 d (range: 3-6 d). The mean blood loss of the hepatectomy was 450 mL (range: 200-700 mL), and the blood loss of the other four was 137 ± 151 mL (range: 50-400 mL). The mean operative time was 318 ± 68 min (range: 236-450 min). The operative morbidity and hospital mortality were zero. The immediate stone clearance rate was 100%. All patients were followed up for an average of 17 mo (range: 7-36 mo). One of the six patients had abdominal mass with pain, and subcutaneous tunnel cholangiography showed severe gallbladder-biliary anastomotic stricture at 4 mo postoperatively. There was no stone recurrence and no cholangitis during follow-up.

CONCLUSION: Laparoscopic hepaticoplasty using gallbladder with a subcutaneous tunnel and preserving the sphincter of Oddi is feasible, safe and effective for hepatholithiasis.

Core tip: The treatment of hepatolithiasis is still a great challenge for surgeons. The residual and recurrent calculi are two major difficulties. This study introduces a new technique for hepatolithiasis and describes its two advantages. The first is that the sphincter of Oddi is preserved and it prevents intestinal reflux, which decreases the postoperative cholangitis rate; the second is that the subcutaneous tunnel is a minimally invasive approach for residual and recurrent stones that avoids reoperation. In selected cases, the operation can be completed via laparoscopy, and this technique is simple and safe.

- Citation: Cui L, Xu Z, Ling XF, Wang LX, Hou CS, Wang G, Zhou XS. Laparoscopic hepaticoplasty using gallbladder as a subcutaneous tunnel for hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(12): 3350-3355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i12/3350.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i12.3350

Hepatolithiasis is prevalent in Southeast Asia but rare in Western countries. The occurrence rate was reported to be 0.6%-1.3% of patients with gallstones in Taiwan, South Korea and China[1,2]. Long-term hepatolithiasis can lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma, and may be a heavy burden on patients[3-5]. In the past, the traditional treatment procedures for hepatolithiasis were common bile duct exploration, resection for fibrous and atrophic liver tissues, and choledochojejunostomy. In recent years, the development of laparoscopic surgery has introduced a minimally invasive method such as laparoscopic hepatectomy[6]. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for the treatment of hepatolithiasis has been widely used in many institutes, but, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports of laparoscopic heapticoplasty with gallbladder for treatment of hepatolithiasis.

Since 1993, an open operative procedure has been introduced in which hepaticoplasty was performed using a free segment of jejunum or gallbladder for a subcutaneous tunnel and preservation of the sphincter of Oddi. The aim was to set up a tunnel between the biliary duct and tela subcutanea in order to remove recurrent stones and drain the bile in recurrent cholangitis in a minimally invasive manner[7]. Since January 2010, a new laparoscopic surgical procedure has been attempted and the results are reported below.

From January 2010 to July 2013, six patients (5 female and 1 male; mean age: 57.8 years, age range: 21-74 years) with hepatolithiasis underwent laparoscopic surgery at our institution. Ultrasonography (USG), computed tomography angiography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were performed preoperatively concerning the stricture location, distribution of calculi, concomitant liver fibrosis and atrophy, and the anatomy of the biliary tree and vascular system.

The indications for laparoscopic surgery were: (1) fit for open surgery (good general condition, no significant organ dysfunction, able to tolerate anesthesia and liver resection); (2) no extrahepatic or future remnant intrahepatic biliary stricture, or no suppurative cholangitis; (3) Child-Pugh class A or B liver function without serious atrophy-hypertrophy complex or severe hepatic portal translocation; (4) no gallbladder size shrinkage and no pathological changes; and (5) no necessity for large hepaticoplasty because of small size of bile duct stricture. Diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma by preoperative imaging, and intraoperative frozen section and postoperative pathological examination findings were not taken into consideration.

Three of the patients had stones in segments II-IV, one in segments V-VI, and two had bilateral stones. In one of the latter two patients, stones were accompanied by hilar bile duct stricture, and both had left lateral hepatic atrophy.

Patients were placed in the Lloyd-Davis position under general anesthesia with tracheal intubation. The primary surgeon stood between the patient’s legs, with one assistant on each side. A CO2 artificial pneumoperitoneum was established with intra-abdominal pressure controlled at 12-14 mmHg. The sites of trocars were similar to those in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The length and site of the common hepatic choledochotomy used were governed by the size and location of the stones, which was at least 3 cm. Detection of intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts was carried out by flexible fiberoptic choledochoscopy (4.9 mm P-20; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) through the choledochotomy to find and remove the stones and to detect any bile duct strictures. Stones were extracted by forceps, stone basket or saline flushing under choledochoscopic guidance. Large impacted stones were fragmented by plasma shock wave lithotripsy[8] and extracted by choledochoscopy.

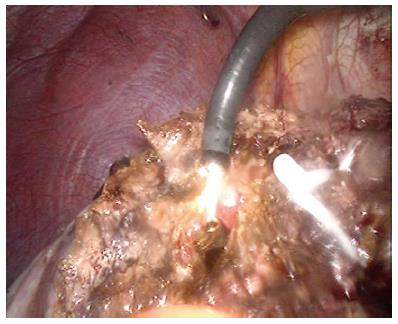

A new trocar was placed at the right subcostal midclavicular line. The round, falciform, left coronary and triangular ligaments were transected with a harmonic scalpel (Olympus). The margin of hepatectomy ran for 1 cm to the left side of the falciform ligament and hepatic transection was continued with the harmonic scalpel to the inferior side of the liver. The hepatic parenchyma was transected gradually along the transection line with the harmonic scalpel or Ligasure (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States). The pedicles of hepatic segments II and III were exposed and transected with titanium clips, hemlock or EndoCutter (Covidien). The left hepatic vein was transected with a linear EndoCutter, and the specimen was placed into the specimen bag. A flexible fiberoptic choledochoscope was used to detect extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts by the orifice of the left hepatic bile duct, remove stones in the hepatic bile duct (Figure 1), and close the orifice by suture. Finally, the raw surface was examined carefully to ensure that there was no bleeding or bile leakage.

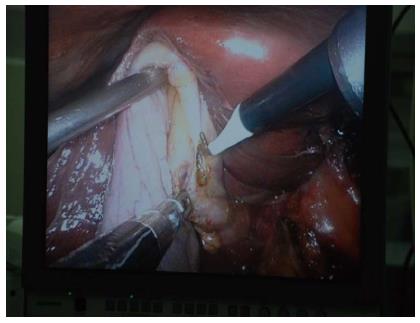

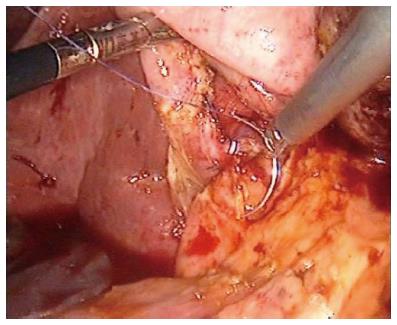

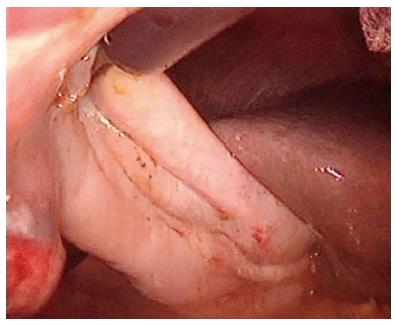

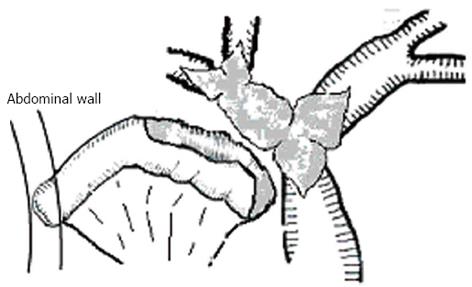

The gallbladder was examined carefully to ensure that its wall was normal. The cystic duct was exposed, cut off and ligated, the cystic artery was preserved to avoid injury, and the neck of the gallbladder was freely separated. The neck of the gallbladder was opened longitudinally at about 3 cm in length (Figure 2); a flexible fiberoptic choledochoscope was inserted into the gallbladder to detect whether the mucosa was normal, and to remove gallbladder stones. If the mucosa was normal, the gallbladder was used as a tunnel. For hilar bile duct stricture, the common hepatic duct was opened longitudinally, stricture of the right and left hepatic ducts was corrected, and the hepatic duct was repaired using the neck of the gallbladder (Figure 3). Side-to-side anastomosis was performed. The gallbladder bed was separated to ensure that the fundus of the gallbladder could be drawn and fixed at the peritoneum and abdominal rectal muscle anterior sheath (Figure 4). The fundus of the gallbladder was about 3 cm × 2 cm on rectus sheath. Finally, the gallbladder fundus was marked on the skin with electrocautery.

For all cases, a T-tube was routinely inserted into the common bile duct for postoperative cholangiography and choledochoscopy.

All patients received the same postoperative care by the same team of surgeons. USG was conducted every 3-6 mo, and then annually, or whenever the patients presented with symptoms suggestive of cholangitis. MRCP or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed if USG showed features of stone recurrence or ductal strictures. If necessary, cholangiography was performed by opening the subcutaneous channel.

All patients successfully completed laparoscopic surgery. The mean length of hospital stay was 4.5 ± 0.9 d (range: 3-6 d). The mean blood loss of the hepatectomy was 450 mL (range: 200-700 mL), and the blood loss of the other four was 137 ± 151 mL (range: 50-400 mL). The operative time was 318 ± 68 min (range: 236-450 min). The operative morbidity and hospital mortality were zero. The immediate stone clearance rate was 100%.

All patients were followed up for an average of 17 mo (range: 7-36 mo). There was no stone recurrence or cholangitis during follow-up. One patient had an abdominal mass with pain, and subcutaneous tunnel cholangiography showed severe gallbladder-biliary anastomotic stricture at 4 mo postoperatively. Considering the subcutaneous tunnel failure, we performed gallbladder chemical ablation with 95% ethanol[9,10] via the subcutaneous tunnel because the patient refused cholecystectomy.

Hepatolithiasis is still endemic in East and Southeast Asia, and is characterized by bile duct stricture and stone formation, causing acute and recurrent life-threatening cholangitis. Repeated cholangitis results in bacterial infection in the biliary system, liver and blood, and leads to liver abscess, sepsis, biliary cirrhosis and even cholangiocarcinoma. To prevent immediate and late sequelae, aggressive treatment is needed.

There are many methods of treatment for hepatolithiasis, such as bile duct exploration and hepatectomy. All of them have the same principles: to remove lesions, extract stones, correct strictures, maintain drainage, and prevent recurrence. In recent years, minimally invasive treatment of hepatolithiasis has developed greatly, including laparoscopy, choledochoscopy, and percutaneous transhepatic choledochoscopy.

Many authors have reported that hepatectomy seems to be the most definitive approach for hepatolithiasis to remove the lesions including stones, strictures, dilation and affected hepatic tissues[11-13]. Laparoscopic hepatectomy has also become possible with the availability of new instruments that allow bloodless liver resection. In 1996, Azagra et al[14] were the first to report laparoscopic hepatic left lateral lobectomy. Since then, there have been many cases of laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis reported, confirming the good short- and long-term effects, high safety, rapid recovery, even for patients with previous biliary operations[15-19].

Although some cases of regional-type hepatolithiasis can benefit from hepatectomy, residual and recurrent stones are still a major challenge for diffuse-type hepatolithiasis. The reasons may include: (1) the lesions of diffuse-type hepatolithiasis are only reduced through hepatectomy and another treatment approach is needed; (2) it is difficult to remove stones thoroughly during surgery for diffuse-type hepatolithiasis, and the stone recurrence rate is high[12]; and (3) postoperative reflux cholangitis related to the method of biliary reconstruction, especially Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, has become an important cause of stone recurrence[20,21].

Reoperation for residual and recurrent hepatolithiasis is difficult, and can impose great physical and mental suffering on patients. After several years of experimental and clinical research, we established a new technique for treatment of residual and recurrent hepatolithiasis and have achieved good results. We performed hepaticoplasty with gallbladder or segmental free jejunum for a subcutaneous tunnel and preserved the sphincter of Oddi. There are two advantages to this technique for residual and recurrent hepatolithiasis: preservation of the sphincter of Oddi and the use of a subcutaneous tunnel.

In recent years, surgeons have paid increasing attention to the preservation of the sphincter of Oddi. The sphincter consists of the ampulla, biliary sphincter and pancreatic sphincter. It regulates the excretion of bile and pancreatic juice, prevents intestinal reflux, and avoids retrograde biliary infection. If the function of the sphincter of Oddi is destroyed, there is a series of pathological changes, such as decreased basal pressure of the sphincter, disappearance of the common bile duct-duodenum pressure gradient, biliary pneumatosis, bacteria in the bile juice, and bile duct chronic inflammation. Thus, many complications such as recurrent bile duct stones, cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma occur[22]. Some authors have reported that patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction tend to have a higher risk of recurrence and a greater demand for reoperation than those without these conditions[23-25]. Therefore, we suggest that the sphincter of Oddi should be preserved if there is no laxity or restriction.

The key point of this technique is to ensure the normal function of the sphincter of Oddi. There are many methods to diagnosis sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, but many of them are invasive[26]. We have found a relatively simple method for intraoperative judgment: if the intraoperative exploration shows that a 16 Fr catheter can pass through the orifice of the duodenum ampulla, the sphincter of Oddi can be considered to have normal function and it should be preserved.

The second feature of this technique is the use of a subcutaneous tunnel as a minimally invasive approach for treatment of residual or recurrent hepatolithiasis. The first case of hepaticoplasty using the jejunum with a subcutaneous tunnel was performed at our institute in 1993. The common hepatic and left and right hepatic ducts were opened longitudinally to form a “basin of hepatic duct”, then a 12-15-cm free pedicled jejunum (anal side) was side-to-side anastomosed with the “basin of hepatic duct” and the oral side of the jejunum was fixed to the abdominal wall (Figure 5).

The gallbladder subcutaneous tunnel is more physiological and convenient than the free jejunum. If no gallbladder shrinkage or pathological changes are found, and there is no need for large-scale hepaticoplasty because of the small size of bile duct stricture, the gallbladder can be used as a subcutaneous tunnel. The anastomosis is not difficult even by laparoscopy. During follow-up, the tunnel can be incised for biliary drainage, cholangiography, choledochoscopic exploration, lesion biopsy, stones clearance, and biliary stricture dilation under local anesthesia whenever the patients present with symptoms suggestive of cholangitis. Also, the tunnel can be marked by electrocautery intraoperatively or by USG postoperatively.

According to our experience, 24% (32/146) of recurrent or residual hepatolithiasis cases underwent biliary drainage, stone clearance and stricture dilation via the subcutaneous tunnel[4]. The high availability enabled the patients to avoid reoperation and fully demonstrated the necessity and value of the subcutaneous tunnel.

In our follow-up, we did not find infection, rupture, volvulus, or increasing stone recurrence rate due to the subcutaneous tunnel. Although the gallbladder-hilar bile duct anastomosis stricture in the present study may have been due to inexperience, we have not found efferent obstruction of the subcutaneous tunnel in any of the other cases.

The difficulty of this technique is the total laparoscopic anastomosis of the gallbladder neck and hilar bile duct. It is necessary to dissect the triangle of Calot carefully, freeing the gallbladder bed, ligating the cystic duct and creating an anastomosis. It also requires intermittent all-layer suture at least 3 cm in diameter.

In summary, this technique reduces postoperative reflux cholangitis rate by preserving the sphincter of Oddi but also provides a minimally invasive treatment for recurrent or residual stones via the subcutaneous tunnel. Also, this technique is simple and safe. However, currently the number of cases is small, and more cases and the long-term effects need further study.

Hepatolithiasis is prevalent in Southeast Asia, especially in China, South Korea and Taiwan, and aggressive treatment is needed because of the sequelae such as biliary cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma. The major difficulties of traditional therapies are serious trauma and high incidence of residual and recurrent stones.

Many studies have shown that hepatolithiasis is a segmental disease along the biliary tree and hepatectomy seems to be the most effective method of treatment. Although laparoscopic hepatectomy is widely used and has achieved good results in localized hepatolithiasis, therapy for diffuse-type hepatolithiasis and the high incidence of residual and recurrent stones are still major challenges. The high incidence of reflux cholangitis caused by traditional hepaticojejunostomy is the major sequela during follow-up. In this study, the authors tried to find a new approach for effective and minimally invasive therapy for hepatolithiasis.

The authors established a minimally invasive approach for hepatolithiasis. The hepatic lesions could be resected laparoscopically, with simultaneous construction of a subcutaneous tunnel. The subcutaneous tunnel enabled them to remove residual or recurrent stones and avoid reoperation. The incidence of intestinal reflux cholangitis caused by traditional hepaticojejunostomy could be avoided by preserving the sphincter of Oddi.

By introducing the technique of laparoscopic hepatectomy and creating a subcutaneous tunnel, this study may present a strategy for treatment of diffuse-type hepatolithiasis and patients with a high risk of residual or recurrent stones.

Hepatolithiasis is located above the confluence of the left and right hepatic ducts, and is a segmental disease that is strictly distributed along the biliary tree. It can lead to secondary biliary cirrhosis and cholangiocarcinoma. The high incidence of residual or recurrent stones and reflux cholangitis are major challenges.

This is a well-written original paper describing an interesting and intelligent technique (hepaticoplasty using the gallbladder) for laparoscopic management of the rare and difficult entity of hepatolithiasis. Satisfactory results are reported.

P- Reviewers: Pavlidis TE, Liu XF S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Sakpal SV, Babel N, Chamberlain RS. Surgical management of hepatolithiasis. HPB (Oxford). 2009;11:194-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Tsui WM, Lam PW, Lee WK, Chan YK. Primary hepatolithiasis, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, and oriental cholangiohepatitis: a tale of 3 countries. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:318-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Han SL, Zhou HZ, Cheng J, Lan SH, Zhang PC, Chen ZJ, Zeng QQ. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of intrahepatic hepatolithiasis associated cholangiocarcinoma. Asian J Surg. 2009;32:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zhang GW, Lin JH, Qian JP, Zhou J. Identification of prognostic factors and the impact of palliative resection on survival of patients with stage IV hepatolithiasis-associated intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee JY, Kim JS, Moon JM, Lim SA, Chung W, Lim EH, Lee BJ, Park JJ, Bak YT. Incidence of Cholangiocarcinoma with or without Previous Resection of Liver for Hepatolithiasis. Gut Liver. 2013;7:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tian J, Li JW, Chen J, Fan YD, Bie P, Wang SG, Zheng SG. Laparoscopic hepatectomy with bile duct exploration for the treatment of hepatolithiasis: an experience of 116 cases. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:493-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xu Z, Ling XF, Wang LX, Hou CS, Wang G, Zhou XS. [Treatment of hepatolithiasis by multiple operative methods with hepatico-subcutaneous stoma]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2011;43:463-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xu Z, Wang L, Zhang N, Deng S, Xu Y, Zhou X. Clinical applications of plasma shock wave lithotripsy in treating postoperative remnant stones impacted in the extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:646-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xu Z, Wang L, Zhang N, Ling X, Hou C, Zhou X. Chemical ablation of the gallbladder: clinical application and long-term observations. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:693-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee TH, Park SH, Kim SP, Park JY, Lee CK, Chung IK, Kim HS, Kim SJ. Chemical ablation of the gallbladder using alcohol in cholecystitis after palliative biliary stenting. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2041-2043. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sato M, Watanabe Y, Horiuchi S, Nakata Y, Sato N, Kashu Y, Kimura S. Long-term results of hepatic resection for hepatolithiasis. HPB Surg. 1995;9:37-41. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Jiang H, Wu H, Xu YL, Wang JZ, Zeng Y. An appraisal of anatomical and limited hepatectomy for regional hepatolithiasis. HPB Surg. 2010;2010:791625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang T, Lau WY, Lai EC, Yang LQ, Zhang J, Yang GS, Lu JH, Wu MC. Hepatectomy for bilateral primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Azagra JS, Goergen M, Gilbart E, Jacobs D. Laparoscopic anatomical (hepatic) left lateral segmentectomy-technical aspects. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:758-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lai EC, Ngai TC, Yang GP, Li MK. Laparoscopic approach of surgical treatment for primary hepatolithiasis: a cohort study. Am J Surg. 2010;199:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tian J, Li JW, Chen J, Fan YD, Bie P, Wang SG, Zheng SG. The safety and feasibility of reoperation for the treatment of hepatolithiasis by laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1315-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cai X, Wang Y, Yu H, Liang X, Peng S. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis: a feasibility and safety study in 29 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1074-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Machado MA, Makdissi FF, Surjan RC, Teixeira AR, Sepúlveda A, Bacchella T, Machado MC. Laparoscopic right hemihepatectomy for hepatolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Di Giuro G, Balzarotti R, Lainas P, Franco D, Dagher I. Laparoscopic left hepatectomy with intraoperative biliary exploration for hepatolithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1147-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kusano T, Isa TT, Muto Y, Otsubo M, Yasaka T, Furukawa M. Long-term results of hepaticojejunostomy for hepatolithiasis. Am Surg. 2001;67:442-446. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Li SQ, Liang LJ, Peng BG, Lai JM, Lu MD, Li DM. Hepaticojejunostomy for hepatolithiasis: a critical appraisal. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4170-4174. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Al-Kawas FH. Long-term outcomes after endoscopic management of bile duct stones: to cut or to dilate? Pay me now or pay me later! Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1192-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liang TB, Liu Y, Bai XL, Yu J, Chen W. Sphincter of Oddi laxity: an important factor in hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1014-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rehman A, Affronti J, Rao S. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: an evidence-based review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:713-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nakeeb A. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: how is it diagnosed? How is it classified? How do we treat it medically, endoscopically, and surgically? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1557-1558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hall TC, Dennison AR, Garcea G. The diagnosis and management of Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: a systematic review. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397:889-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |