INTRODUCTION

End-stage liver disease due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the leading indication for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) in Western countries[1]. HCV reinfection is virtually universal after OLT, and up to 70% of patients are expected to experience histological recurrent hepatitis C[2-13], with a higher risk of graft loss and mortality compared to recipients undergoing transplantion for other etiologies[5,14-16]. It is noteworthy that the incidence of HCV disease in allografts has increased since the nineties according to the literature, probably due to the application of more effective immunosuppression regimens. Indeed immunosuppression, especially the steroid boluses given in the case of acute cellular rejection (ACR), inevitably accelerate the virus-mediated graft damage, with a more aggressive course compared with HCV disease in native livers[17-20]. Although some authors have recently underlined a good outcome of HCV-positive recipients at 5 years after OLT[13], recurrent hepatitis C still represents the major cause of graft failure.

In this setting, it is now recognized that the histopathological analysis of post-OLT liver biopsies can produce valuable data for the diagnosis and prognosis of recurrent hepatitis C, and therefore for the management of HCV-positive recipients, though in this case, no universal approach is recognized. Moreover, the histopathological diagnosis of recurrent hepatitis C implies many pitfalls and a wide range of differential diagnoses, and it can be very challenging especially in the early post-OLT phases.

The present review focuses on the role of pathologist and pathology laboratory in the diagnosis of recurrent hepatitis C, the objective usefulness of early and late post-OLT liver biopsies, and the potential role of ancillary techniques in the diagnosis and prediction of the disease progression.

LIVER BIOPSY IN EARLY ACUTE RECURRENT HEPATITIS C

The timing and the indications of post-OLT liver biopsies represent a key step in the management of HCV-positive recipients. Although the decision is normally made by the surgical team, and therefore does not directly involve the pathologist, the practice of protocol biopsies after OLT might influence the whole transplant team.

As early recurrent hepatitis C, as well as the early allograft damage that can simulate it, are clinically and serologically evident, early liver biopsies are usually performed for established clinical indications. Moreover, complications after liver biopsy are rare but potentially serious, and the histopathological report of a biopsy performed with normal tests does not usually influence the therapeutic approach[21]. For these reasons, there has been a progressive cessation of early protocol biopsies in many centers. In our center, protocol biopsies are not performed, and we introduced the concept of “first-event” biopsy. The “first-event” biopsy is defined as the biopsy taken at the very first increase in transaminase level and/or clinical worsening after OLT[22]. Although we realize that this approach cannot be free from selection bias, the histopathological and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) studies of the tissue obtained from the “first-event” biopsies can provide valuable diagnostic and prognostic data on HCV recurrent disease (see also the RT-PCR section)[22,23].

The onset of “typical “ acute recurrent hepatitis C is generally recorded within 4-12 wk after OLT, but according to Demetris, it “can be detected as early as 10 to 14 d”[12]. Saraf et al[24] reported a case of a woman who experienced recurrent hepatitis C at day 9, attributing the early onset to the advanced donor and recipient ages. In our most recent experience, 75% of HCV-positive recipients had a histopathological diagnosis of recurrent hepatitis C after a mean of 86 d, but with a high variability, including a case of recurrent hepatitis C after 3 d[22]. This finding is in agreement with Pacholczyk et al[13], who reported the minimum recurrence time in their series at 5 d. These “extreme” cases of early recurrent hepatitis C are very rare, but they are not to be excluded a priori, also taking into account HCV virulence and immunosuppression suitability. In any case, experience has taught us that the diagnosis of recurrent hepatitis C after such a short period requires tissue HCV RNA quantitation, as well as the clinical and histopathological exclusion of other possible causes of graft damage, e.g., ACR, early surgical complications, ischemia/reperfusion injuries, and other early complications, which have a much higher incidence in the first days after OLT.

HISTOPATHOLOGY OF EARLY RECURRENT HEPATITIS C

Typical acute recurrent hepatitis C

On the basis of nearly 20 years of publications, Demetris classified the histopathological presentation of recurrent hepatitis C into three groups: the “typical” presentation (acute and chronic), fibrosing cholestatic HCV hepatitis (FCH), and a plasma cell-rich variant[12]. Each of these histopathological variants can be intertwined with other post-OLT complications (ACR above all).

Lobular hepatitis observed in “typical” acute recurrent hepatitis C is similar to the acute viral damage observed in the very first phases of hepatitis C in non-transplanted livers, but has very low (or absent) portal tract involvement. In particular, early recurrent hepatitis C is characterized by lobular architectural disarray with Councilman bodies and spotty necrosis, Kupffer cells activation, and mild lymphocytic sinusoidal infiltrate[1,12,25,26] (Figure 1). The Councilman bodies (or acidophilic bodies) are the expression of the apoptotic death of hepatocytes during lobular damage. The formation of apoptotic bodies was described during hepatitis C, both in native livers and OLT allografts, as a consequence of several mechanisms including direct cytotoxicity by HCV, activation of the extrinsic apoptotic pathway by the recipient immune system, and sensitization to the FasL/CD95 intrinsic pathway by HCV core proteins[27-29]. In the OLT setting, the morphological features are further complicated by immunosuppression. The first quantitation of Councilman bodies in the allograft differential diagnosis was performed in 2002 by Saxena et al[30], who found a two-fold higher mean number of apoptotic bodies per cm2 in recurrent hepatitis C than in ACR. The authors also suggested that the finding of > 50 acidophilic bodies in the whole biopsy was strongly indicative of recurrent hepatitis C[30]. Some years later, in order to obtain more reproducible results, our group evaluated the so-called “Councilman bodies/portal tract ratio” (“C/P ratio”), which simply represents the mean number of Councilman bodies for each portal tract counted in the biopsy[22,23]. The C/P ratio was the only histopathological variable able to discriminate recurrent hepatitis C from other conditions, as well as the only variable directly correlated with the intrahepatic HCV RNA load. Moreover, high-risk recipients showed more Councilman bodies than others, with a mean C/P ratio of 1.5 (see below)[22].

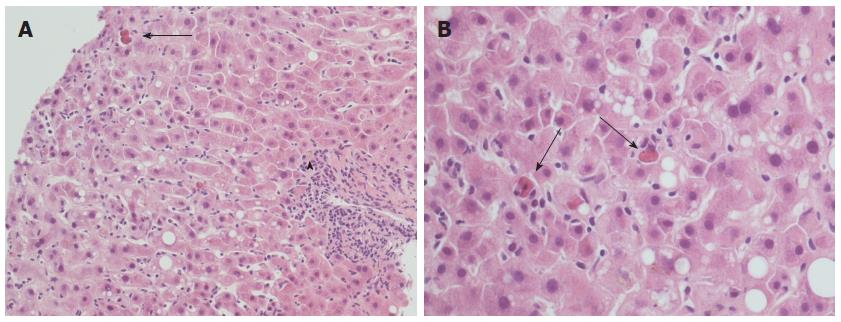

Figure 1 Typical histopathological appearance of acute recurrent hepatitis C.

A: Lobular architectural disarray, lobular necrosis with lymphocytic sinusoidal infiltrate and visible Councilman bodies (black arrow) are evident, as well as a mild portal tract inflammation (arrowhead); hematoxylin-eosin stain, × 20 magnification; B: Detail of the same case at × 40 magnification: note the high number of Councilman bodies in a single field (black arrows), and a minimal amount of macrovesicular steatosis.

Histopathological variants: Fibrosing cholestatic HCV hepatitis

FCH is a quite peculiar presentation of recurrent hepatitis C, although it was first described in a HBV-positive OLT recipient[31]. FCH is characterized by an early onset (within 1 year) and an overall poor prognosis, due to the rapid fibrosis progression and the poor response to conventional antiviral therapies[6,32]. At histology, FCH shows hepatocyte swelling and ballooning, spotty necrosis with Councilman bodies, cholestasis with ductular reaction and a ductular-type interface activity, with a mild mixed portal infiltrate (Figure 2A-C). Late alterations include periportal fibrosis and cirrhosis (Figure 2D)[6,12,32-35]. In a previous study on 10 FCH cases (on 135 HCV-positive recipients), the median hepatitis activity grade and the Banff score were significantly higher than in “usual” acute recurrent hepatitis C[34]. The occurrence of a peculiar sinusoidal pattern of fibrosis was also described as important for the diagnosis of FCH[34]. According to a recent paper, the diagnosis of “cholestatic HCV” requires at least three out of four histological features (ductular reaction, cholestasis, hepatocyte ballooning and periportal sinusoidal fibrosis), 1 mo after OLT, after exclusion of other causes of cholestasis. These histological features seem to have a prognostic meaning as well[35].

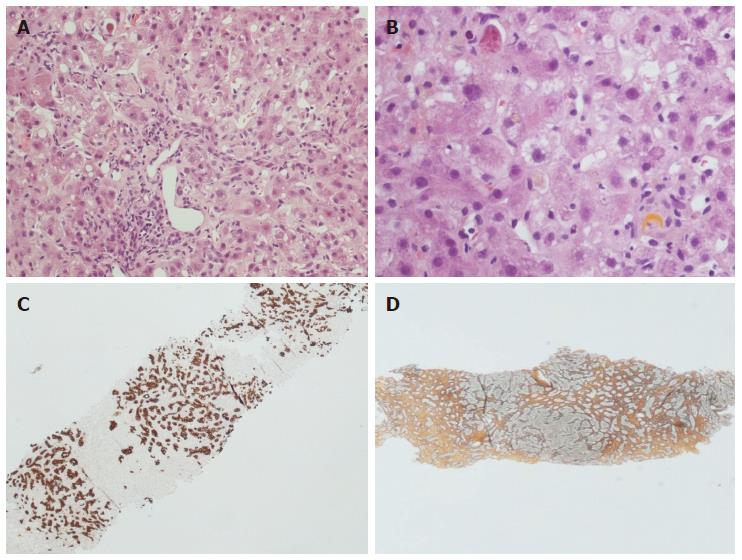

Figure 2 Histopathological appearance of fibrosing cholestatic recurrent hepatitis C.

Hematoxylin-eosin stain × 10 (A) and × 40 (B) magnification: note the lobular architectural disarray, the portal tract fibrosis and distortion, the lobular necrosis with Councilman bodies and the cholestasis with hepatocellular feathery degeneration and ballooning. The immunohistochemistry for keratin 19 (C) highlights the prominent ductular reaction, while the reticulin stain (D) indicates advanced fibrosis.

FCH is likely to affect over-immunosuppressed recipients[36], with a massive viral replication, as reflected by the occurrence of very high viral loads in both serum and liver tissue, as reported in different papers from the end of the nineties[22,33,37]. Notably, in one paper, the tissue HCV RNA levels in the native explanted liver correlated with a higher risk of FCH[38].

Histopathological variants: Plasma cell-rich recurrent hepatitis, a still open issue

In 2007, Khettry et al[11] described nine cases (10% of their series) of recurrent hepatitis C with periportal and centrolobular necrosis and inflammation, characterized by a prominent plasma cell component. The authors named this entity “post-liver transplantation autoimmune-like hepatitis” and postulated that the interplay among the recipient’s immune system, HCV replication and antigenicity, and immunosuppression therapy might occur in the development of this “hyperimmune” inflammatory reaction. Furthermore, although on the basis of non-scheduled biopsies, this “autoimmune-like hepatitis” seemed to be related to fibrosis progression[11]. In the same period, Fiel et al[39] highlighted that more than 80% of “plasma cell hepatitis” in their series occurred after a reduction in immunosuppression (calcineurin inhibitors), and that 55% had at least one previous episode of rejection. These findings led the authors to the conclusion that the plasma cell hepatitis was a form of rejection. An editorial by Demetris et al[45] in the same year underlined that HCV can stimulate some types of autoimmune alterations both in allografts and native livers[12]. Moreover, antiviral therapy can unleash “autoimmune-mediated” liver damage, as described for pegylated-interferon with or without ribavirin[40-43]. Finally, a case-control study described the worse prognosis of plasma cell-rich hepatitis, which interestingly was also correlated with the presence of plasma cells in the explanted liver in one study, suggesting the existence of an immunological “disposition” in some patients[44]. In 2009, Demetris classified the plasma cell-rich “autoimmune” hepatitis as a histopathological variant of recurrent hepatitis C, albeit stating that “determining whether this represents an autoimmune variant of HCV, acute rejection, actual autoimmune hepatitis, or a combination of these possibilities requires a more thorough patient evaluation than what is currently done at most centers and further study”[12,45].

Histopathological variants: recurrent hepatitis C with granulomas

Not included in the Demetris’ classification of 2009[12], was the possibility of a liver granulomatous reaction as presentation of HCV recurrent disease, first postulated in a case reported by Bárcena et al[46], although HCV was already listed as a possible cause of post-OLT granulomas in a series of 42 recipients in 1995[47]. Ten years later, non-necrotizing lobular (more rarely portal) granulomas were observed in unscheduled biopsies of four (8%) out of 53 HCV-positive recipients[48]. After the exclusion of other etiologies, the authors ascribed the granulomatous disease to hepatitis C. In another retrospective study in the same period, granulomas were found in 14 (1.7%) out of 820 HCV-positive recipients[49]. In this series, 10 cases were found on protocol biopsies, and four on biopsies performed for clinical indications: the prevalent lobular localization of the granulomas was confirmed, and since most patients received pegylated interferon, the authors hypothesized that “granuloma formation may be indicative of antiviral stimulation against intrahepatic HCV”[49]. The question whether this very rare biopsy finding represents a form of antiviral immune reaction, ultimately drug-modulated, still remains open, as is the role of the granulomatous reaction in fibrosis progression and graft survival.

“CHOLESTATIC” RECURRENT HEPATITIS C: PROGNOSTIC ROLE OF POST-OLT LIVER BIOPSY

Apart from the assessment of fibrosis progression, which will be discussed below, histopathological evaluation can play a prognostic role in the identification of those morphological features predictive of a worse outcome. In addition to some still debated histopathological characteristics, e.g., steatosis[50,51], apoptosis, or bile duct proliferation[52], another feature with a well-known impact on recipient outcome is cholestasis (Figure 3). The relationship between cholestasis and a more severe form of recurrent hepatitis C is well established[6,53]. Recently, Moreira et al[54] proposed the so-called “Histological Aggressiveness Score”, based on the presence or absence of a prominent ductular reaction, hepatocellular ballooning, cholestasis, and periportal/sinusoidal fibrosis, all features typical of the most severe form of recurrent hepatitis C, i.e., FCH. In this study, 170 recipients were stratified into three risk groups using these four histopathological features, which are not included in the conventional grading systems of chronic hepatitis[54]. In our recent experience, the occurrence of a cholestatic recurrent hepatitis C was associated with a significantly higher tissue HCV RNA, and also with a poorer outcome[22]. Although we agree that FCH is by far one of the most aggressive forms of recurrent hepatitis C, we also believe that severe HCV recurrence is not always an indication of FCH. In our routine experience, more “traditional” features such as the amount of lobular necrosis (i.e., Councilman bodies), as well as the quantitation of intrahepatic HCV RNA (as mentioned below), are strong predictors of a poor outcome as well. Nonetheless, our results are in agreement with Moreira’s, since 35% of our “high-risk group” (or group 3, with both tissue and serum high viral loads) experienced a cholestatic recurrent hepatitis C[22]. It should be borne in mind that Moreira et al[54] excluded recipients with post-OLT biliary complications from their study; conversely, we included these recipients in our series, since a connection between recurrent hepatitis C and post-OLT biliary complications has been previously proposed[55]. We found that most recipients with previous biliary complications belonged to the “high risk group”[22]. Future studies are required to investigate the intriguing cross-connection among biliary complications, HCV replication and recurrent hepatitis C.

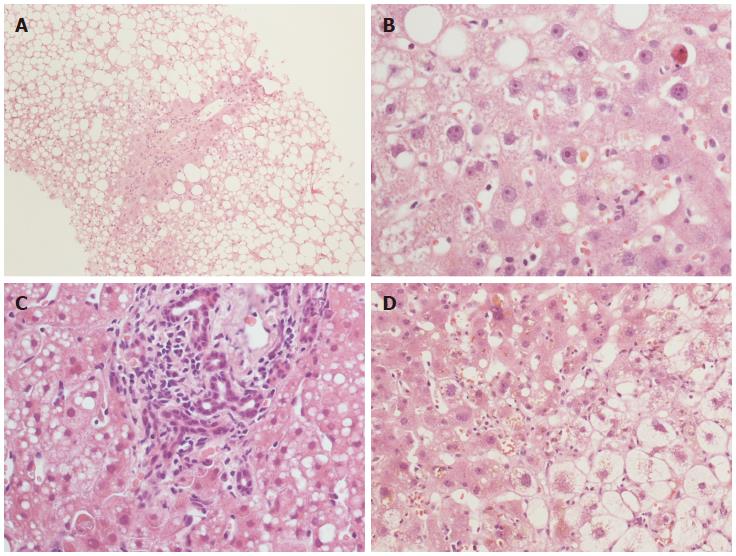

Figure 3 Histopathological features with a prognostic significance in recurrent hepatitis C.

Steatosis (A) and cholestasis (B) are well shown. Cholestasis can be associated with bile duct proliferation (C) and/or hepatocellular ballooning (D). Hematoxylin-eosin stain, × 10 (A) and × 40 (B-D) magnification.

CHRONIC RECURRENT HEPATITIS C: THE PROTOCOL LIVER BIOPSY QUESTION

Protocol biopsies and fibrosis progression

Chronic (late) recurrent hepatitis C generally presents 6-12 mo after OLT. The main morphological features are portal tract inflammatory infiltrate, mostly composed of lymphocytes, with interface hepatitis and ductular reaction; the lobular necrosis with hepatocellular polymorphism persists depending also on the response to anti-viral therapy[4,12,20,56]. The overall picture becomes similar to the histopathological presentation of C hepatitis in native livers. The differential diagnosis of chronic recurrent hepatitis C is usually not difficult for the pathologist, because of the typical histological picture, and because the diagnosis of hepatitis C in liver allograft has already been made on clinical grounds, if not with a previous biopsy. Therefore, there is no full agreement on the usefulness and indications of liver biopsy in this phase, since fibrosis progression in allografts represents the only valuable parameter in the long term for prediction of OLT outcome[10,57-60]. The severity of fibrosis progression in the allograft is determined early: some authors demonstrated that hepatitis grade and fibrosis stage within the first year after OLT might identify those patients with a possible rapid fibrotic evolution[18,52,61]. In order to evaluate and follow fibrosis progression, some centers adopt annual protocol liver biopsies, while others favor the clinical follow-up, with the execution of biopsies only in the case of an increase in transaminase levels or worsening of the clinical picture.

In a first key study conducted on recipients followed by protocol biopsies, Gane et al[5] concluded that recipients with moderate chronic hepatitis at 1 year bore a significantly higher risk of cirrhosis development at 5 years, than recipients with mild hepatitis activity. Years later, large analyses on the usefulness of long-term protocol biopsies showed that the proportion of healthy allografts tended to decrease with time after OLT[62,63]. Moreover, in a series of 245 patients with at least 1 year of follow-up the presence of normal transaminase levels virtually excluded liver damage in non-HCV recipients, while in HCV-positive recipients, the serum tests seemed to be less sensitive, and the authors concluded that the long-term protocol biopsies were useful to assess the progression of recurrent hepatitis C[62]. This is confirmed by the fact that most centers worldwide do not perform long-term protocol biopsies for indications other than HCV[21], while in HCV-positive recipients protocol biopsies are still applied in most centers.

The assessment of the hepatitis grade is important as well, as it correlates with staging and fibrosis progression[57,64,65]. Firpi et al[66] found that a fibrosis stage > 2 according to Ishak and/or an hepatitis activity index > 4 at 1 year correlated with a faster fibrosis progression. In a highly selected series of patients, Baiocchi et al[67] found a strong relationship between grade (especially portal inflammation) and fibrosis progression after 1 year. Furthermore, in a series of 159 patients, Ghabril et al[68] found that the HCV activity grade (Ishak > 4) even in the explanted liver was predictive of a more rapid graft fibrosis progression after OLT.

In a series, the fibrosis progression in HCV-positive recipients was calculated as 0.8 units (according to Ishak) per year; interestingly, this mean value increased with donor age > 55 years, and decreased with donor age < 35 years[66]. Donor age was confirmed to be an important predictor of faster fibrosis progression in HCV-positive recipients also in further studies[69-74], although not in others[65,75]. Other risk factors include viral quasi-species, number of episodes of ACR, and changes in immunosuppression, as well as the sustained virological response to antiviral therapy[52,58,76].

Graft steatosis in recurrent hepatitis C

Steatosis is another long-term histopathological alteration that was firstly considered specific of HCV recurrent disease after OLT in the past[77], especially in association with the HCV genotype 3[78,79], and it was described also in C hepatitis in non-transplanted livers[80]. Recently, Brandman et al[50] have confirmed the presence of some degree of steatosis in nearly 30% (45 out of 152) HCV-positive recipients 1 year after OLT, especially with genotype 3 infection. HCV can directly induce steatosis by alteration of mitochondrial functions or by interference with the lipid metabolism pathway[79]. However, many factors other than HCV infection are likely to play a role in graft steatosis, including donor-specific characteristics such as donor age, or the occurrence of pre-transplant hypertension[50]. This issue surely deserves further studies, since post-OLT steatosis and metabolic syndrome seem to be related, with a higher risk of fibrosis progression 1 year after OLT[50,70,81,82], although not all investigators agree[83,84].

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES OF RECURRENT HEPATITIS C

Recurrent hepatitis C vs acute cellular rejection

The most important differential diagnosis in the early post-transplant phases lies between recurrent viral hepatitis and ACR, especially of mild grade, and is primarily based on liver biopsy[12,26]. Actually, fully reliable guidelines clearly distinguishing recurrent hepatitis C from mild ACR at histology are not available yet, and the diagnosis is still characterized by low inter- and intra-observer agreement[85]: pathologist experience and the interplay between clinician and pathologist play a pivotal role in diagnosis and recipient management. The more characteristic histopathological features of early recurrent hepatitis C are lobular necrosis, steatosis, and Kupffer cell hyperplasia[26,30,32]. Conversely, the commonest findings in ACR include mixed portal tract inflammatory infiltrate with interface hepatitis, bile duct damage and venulitis, with or without lobular damage[30,86,87] (Figure 4), although in mild ACR these morphological features can be lacking in small biopsies. Since ACR and recurrent hepatitis C often co-exist in the same allograft[12], and since early HCV recurrent disease can sometimes mimic some ACR features (e.g., venulitis or biliary damage)[88,89] (Figure 4C and G), it was also suggested that the Banff criteria should be downgraded in HCV-positive recipients. For example, ACR should be diagnosed only in cases with > 50% of portal tract inflammation with biliary damage and/or > 50% of venulitis[26]. The relevance of this topic is that an ACR over-diagnosis might lead to over-immunosuppression, with serious consequences on HCV replication and graft survival. In fact, in order not to lose any graft to rejection, it is the protocol of many institutions to give the recipient a steroid bolus even only on the basis of a clinical suspicious of ACR, sometimes without liver biopsy. Although the typical features of ACR and HCV recurrence are easily recognizable when singularly present, the “overlap” of the two conditions still represents a challenge for the pathologist; in our institution RT-PCR for HCV RNA quantitation is mostly used for this differential diagnosis, as also suggested by others[23,28,90,91]. Other important, albeit less frequent conditions that are included in the differential diagnosis with early recurrent hepatitis C are ischemia/reperfusion injury, post-OLT surgical complications, and drug reactions. Of note, the occurrence of preservation injuries in HCV-positive recipients was correlated with a poorer outcome[92].

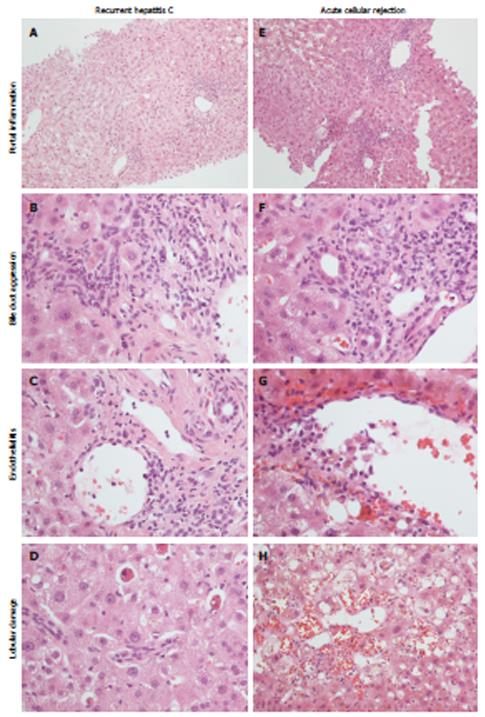

Figure 4 Histopathological appearance of recurrent hepatitis C (left) and acute cellular rejection (right).

Portal inflammation is commonly mild in recurrent hepatitis C (A), with a predominant lympho-monocytic infiltrate and mild bile duct invasion (B), while in acute cellular rejection there is a mixed and more pronounced inflammatory infiltrate (E), with evident bile duct invasion (F). Endothelialitis can be found in both conditions (C, G). Lobular necrosis is more typical of recurrent hepatitis C (D); in acute cellular rejection hemorrhage and sinusoid dilatation are more evident (H).

Other differential diagnoses

The FCH histopathological picture is quite peculiar, and the main differential diagnoses include: ischemic injury due to hepatic artery thrombosis, extrahepatic biliary obstruction, adverse drug reactions, and chronic rejection (after 6 mo). All these conditions are characterized by hepatocyte ballooning, perivenular centro-lobular necrosis, cholestasis and Kupffer cell activation, as seen in FCH[32,35,93]. However, some features are distinctive of particular conditions, such as pilocytic neutrophil infiltrate in ascending cholangitis, portal edema, ductular reaction with neutrophils, and periductular fibrosis in large bile duct obstruction, and a scarcity of biliary ducts with mild portal inflammation in chronic rejection. In this latter case, the timing is important too. Finally, the distinction between FCH and “typical” recurrent hepatitis C, with or without fibrosis or cholestasis, is mainly based on the rapidity of graft failure and the lack of response to antiviral therapy. However, histology alone cannot be enough for a certain diagnosis of FCH, and the clinical picture, together with HCV RNA quantitation are required[94].

As discussed above, the differential diagnosis of plasma cell-rich hepatitis is very difficult, also because the distinction between “autoimmune” damage, “hyperimmune” damage (HCV- or drug-induced), and “alloimmune” damage (i.e., a plasma cell-rich rejection) is not always sharp. The clinical setting is crucial for the correct diagnosis of the recipient: the occurrence of de novo autoimmune antibodies (antinuclear antibodies, smooth muscle antibodies, LKM1 > 1:320 and anti-GSTT1), a concurrent autoimmune disease and/or the serum markers can lead to the diagnosis of de novo autoimmune hepatitis[12,39]. According to a recent proposal by Fiel et al[39], a diagnosis of de novo autoimmune hepatitis is recommended when plasma cells represent at least 30% of the total inflammation, and interface hepatitis and lobular necrosis are mainly represented by plasma cells.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a common complication of OLT (up to 17%)[95], and is not likely to influence the course of HCV disease or ACR[96]. Since the distinctive features of CMV infection (e.g., nuclear inclusions) are frequently absent in the post-OLT biopsy, lobular necrosis and disarray together with variable portal inflammation can add to the differential diagnosis in early recurrent hepatitis C[95]. Other non-specific, albeit helpful morphological findings in CMV infection, apart from the typical inclusions, are represented by mild bile duct damage, lobular microabscesses and lobular microgranulomas. In cases where CMV infection is suspected, specific immunohistochemistry (IHC) is recommended.

Chronic recurrent hepatitis C is characterized by a portal mononuclear infiltrate with variable degrees of interface hepatitis. The biliary damage can be present, but it is not as severe and/or widespread as in chronic rejection, where bile duct regression can be the prevalent feature, also in the absence of inflammatory infiltrate[12].

ANCILLARY TECHNIQUES: IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

HCV detection in liver tissue

Since the nineties, many studies have tried to investigate the possible use of IHC to establish the presence of HCV antigens (mainly nonstructural antigen 4 or NS4, and c-100) in liver tissue. Notably, almost all these studies identified some grade of IHC positivity in HCV-positive patients, but without correlations with the histological findings and the clinical data[97-101]. However, it must be borne in mind that these IHC techniques often lacked reproducibility between laboratories, and cross-reactions were found in some cases[37,102].

Ballardini et al[103] first applied IHC for different HCV antigens (c100, c33, c22, NS5) in HCV-positive OLT recipients, and showed that IHC positivity appeared in hepatocyte cytoplasm “in almost all livers at day 20 post-OLT”[104]. Among the cases with acute lobular hepatitis, a median of 80% of positive hepatocytes was found, while in all other cases the percentage positivity was never greater than 30%[103]. The authors concluded that IHC might be used to support the diagnosis of recurrent hepatitis C when histology alone was not conclusive[104]. Studies from our group confirmed a strong correlation between IHC positivity in hepatocyte cytoplasm and intrahepatic viral load with RT-PCR[23,105]. IHC detection of HCV was associated with the typical histopathological features of hepatitis C (hepatocyte single-cell necrosis, bile duct damage, cholestasis, lymphoid aggregate) in a single study[106], while in another paper post-OLT IHC positivity for anti-HCV core proteins correlated with IHC positivity in explanted livers and with the development of a cholestatic recurrent hepatitis C[107]. Finally, a recent work with a monoclonal antibodies against HCV-envelope 2 found a stronger positivity in definite or probable recurrent hepatitis C than in other conditions (including ACR)[108]; this IHC positivity did not correlate with HCV RNA serum levels.

Hepatic stellate cell activation

IHC has been used in the investigation of some features which can indirectly be related to recurrent hepatitis C diagnosis and progression. Some papers of the same period applied IHC for α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in order to detect activated mesenchymal hepatic stellate cells (HSC) in the portal tracts and fibrous septa in OLT specimens from HCV-positive recipients[109-111]. The amount of α-SMA-positive cells were predictive of recurrent hepatitis C with high histological activity, leading to an HSC-mediated rapid fibrosis[110], regardless of the amount of collagen deposition measured by the trichrome stain[111]. For the study of HSC activation in recurrent hepatitis C, glial fibrillary acid protein has also been proposed and compared with α-SMA[112].

Meriden et al[52] have studied keratin 19 (K19) in bile duct proliferation and the expression of vimentin in HSC, portal mesenchymal cells and some biliary epithelial cells, with an increased expression of both markers in those patients with faster fibrosis progression, independently of the amount of collagen deposition as measured by Sirius Red. Early activation of HSC preceding collagen deposition was also described and, together with bile duct proliferation, was determined to play a role in fibrosis progression.

Other applications of immunohistochemistry

Claudin-1 protein is a tight junction protein expressed mainly on the apical-canalicular site of hepatocytes, and represents one of the most important HCV receptors. A recent study by Zadori et al[113] on 12 HCV-positive allografts found that cases with low apical Claudin-1 IHC expression at 1 year after OLT had a better response to antiviral therapy. Moreover, a correlation between Claudin-1 and the degree of fibrosis was found.

As far as the differential diagnosis between recurrent hepatitis C and ACR is concerned, some markers have been proposed. The utility of IHC for C4d is still debated: some preliminary analyses reported that C4d tissue positivity, detected by means of IHC or immunofluorescence, was markedly higher in rejection cases than in recurrent hepatitis C[114-116]. However, a more recent study found C4d positivity in 17.6% of ACR biopsies vs 25.9% of recurrent hepatitis C[117]. These results illustrate the controversial use of C4d for routine diagnosis.

MacQuillan et al[118] studied the expression of MxA protein, a GTPase involved in interferon pathway activation, on 14 HCV-positive OLT patients, and found higher MxA expression in hepatocytes and monocytes of recurrent hepatitis C cases. These results are in contrast with Borgogna et al[119], who found a positive correlation between MxA expression and ACR, although they also observed a lower rate of fibrosis progression in patients with recurrent hepatitis C and concomitant strong MxA expression. These studies included cases with HCV-ACR overlap and cases treated with steroid boluses, which were likely to further confuse the scenario, and according to the same authors, validations on wider series are required.

The IHC evaluation of the cell-cycle marker minichromosome maintenance protein-2 (Mcm-2) was also proposed in the literature: a single study found up to 24% of Mcm-2 positive hepatocytes in recipients who later developed fibrosis, vs 5% of patients without fibrosis[120]. Moreover, the portal tracts in ACR biopsies were reported to show more Mcm-2-positive lymphocytes, than in recurrent hepatitis C biopsies[121].

ANCILLARY TECHNIQUES: RT-PCR

HCV RNA quantitation in liver tissue

The first study of tissue HCV RNA quantitation was carried by Di Martino et al[122] on 84 biopsies from 33 HCV-positive recipients and HCV RNA was markedly higher in biopsies of HCV recurrence with lobular hepatitis, regardless of the occurrence of genotype 1b. Moreover, tissue HCV RNA seemed to decrease in the transition from lobular (acute) hepatitis to chronic hepatitis C, probably due to the host’s response against HCV in the long term. Finally, an interesting positive correlation between the levels of HCV RNA at the first pre-transplant biopsy and the risk of chronization was found[122]. In the same year, Cirocco et al[90] confirmed on a series of 23 biopsies that tissue HCV RNA was significantly higher in recurrent hepatitis C cases than in other allograft conditions: moreover, the same authors confirmed these data using in situ RT-PCR on 25 recipients[123]. According to Aardema et al[124], who studied four sequential protocol biopsies in 26 recipients, intrahepatic HCV RNA was directly related to the degree of lobular hepatitis, but not to serum HCV. A semi-quantitative analysis of the HCV intermediate RNA filament, a marker of viral replication, showed that HCV started replicating very early after OLT: interestingly, this replication correlated with the other viral antigens, but neither with histological hepatic damage nor with serum HCV[125]. A further semi-quantitative PCR analysis on non-protocol biopsies showed that intrahepatic HCV RNA correlated with Fas mRNA and DNA fragmentation, which represent important indexes of liver cells apoptosis[28].

Gottschlich et al[91] confirmed in 2001 the usefulness of tissue HCV RNA quantitation in the differential diagnosis between recurrent hepatitis C and ACR, on 72 biopsies from a series of 36 OLT recipients. After stratifying the recipients into different histopathological groups, i.e., recurrent hepatitis C (probable and definite), indeterminate, and ACR (probable and definite), they noticed significantly higher HCV RNA levels in the HCV groups, even if the “probable rejection” group had high levels as well. The authors hypothesized that ACR episodes might be able to increase viral replication or, more likely, that recurrent hepatitis C and ACR can coexist, with hepatitis C as the predominant process. The conclusions were that recipients with low intrahepatic HCV RNA were not likely to have recurrent hepatitis C, although high HCV RNA did not exclude ACR[91].

Starting from these assumptions, in 2008 our group carried out RT-PCR quantitation of non-scheduled biopsies from 65 consecutive HCV recipients: in this work we confirmed that intrahepatic HCV RNA correlated with IHC positivity for viral antigens and Councilman bodies (C/P ratio, see above), and we described a 73% sensitivity and 85% specificity for RT-PCR in discriminating recurrent hepatitis C from other conditions, assuming a cut-off value of 1.1 IU/ng[23]. One year later, in a methodological study on 215 biopsies, we described the correlation between intrahepatic HCV RNA and IHC, serum HCV RNA, and the main liver serum markers[105]. Finally, we recently proposed that the quantitation of HCV RNA on the “first biopsy”, together with the serum HCV RNA, might have a prognostic impact. Indeed, on the basis of tissue and serum HCV RNA loads, we stratified 83 HCV recipients into three categories: (1) tissue HCV RNA ≤ 1.5 IU/ng with any serum HCV RNA (68% recurrence rate and 0% HCV-related mortality); (2) tissue HCV RNA > 1.5 IU/ng and serum HCV RNA < 4 × 107 copies/mL (91% recurrence rate and 14% mortality); and (3) tissue HCV RNA > 1.5 IU/ng and serum HCV RNA ≥ 4 × 107 copies/mL (100% recurrence rate and 45% HCV-related mortality). Moreover, we lowered the diagnostic cut-off value to 0.85 IU/ng, with 89% sensitivity and 71% specificity[22]. Prospective studies on larger series are required in order to confirm the true prognostic value of HCV RNA quantitation, and it is our opinion (together with Gottschlich)[91] that RT-PCR alone can be misleading, and it must always be interpreted in the context of the overall clinical and morphological background.

Interleukin-28B polymorphism

Apart from the quantitation of serum and intrahepatic viral load, RT-PCR technology has recently also been applied in the study of recipient genetic variability, such as the case of interleukin 28B (IL-28B), or type-III interferon, whose polymorphism has been correlated with the response to antiviral therapy, or even spontaneous viral clearance, in hepatitis C[126]. As for the OLT setting, in an intriguing case report of a recipient engrafted with two liver lobes from two different living donors, different stages of fibrosis and different tissue HCV RNA were found in the two grafts after 2 years; the authors attributed this diversity to the IL-28B genetic variants in the two grafts[127]. In recent studies, different rates of sustained virological response to therapy were reported according to the presence or absence of “favorable”IL-28B genotypes (C/C and/or T/T genotype, according to the different studies) both in donor and recipient livers[128-132]. Moreover, recipient IL-28B“non-C/C genotype” was an independent risk factor for cholestatic recurrent hepatitis C[133]. As underlined by Fabris et al[134] in non-transplanted HCV patients, and also in OLT recipients, the decision about antiviral therapy is driven by clinical indications, such as transaminases level and HCV genotype, and nowadays donor/recipient genotyping still does not help the clinician in the decision. However, we guess that the application of these technical procedures on donor and recipient tissue will represent a valid aid for the pathologist (and the clinician) for the routine management of HCV-positive recipients in the future.

Other cytokines analyzed by RT-PCR in the post-OLT HCV setting are IL-2 and IL-4: in a series of 52 OLT recipients and 22 non-transplanted patients, Dharancy et al[135] found that IL-4 expression was high in severe hepatitis recurrence C cases, and lower in mild HCV infection and HCV-negative cases; IL-4 expression was confirmed in tissue by means of IHC.

Nowadays, molecular techniques such as microarrays have been validated for use in the differential diagnosis between recurrent hepatitis C and ACR[136]; this issue is not discussed in the present review.

CONCLUSION

Although the morphological features of recurrent hepatitis C have been well described in the last few decades, differential diagnosis can still represent a challenge for pathologists, especially in the setting of early recurrent hepatitis C and mild ACR. In addition to the clinical data, essential for the exclusion of other pathological conditions, many ancillary techniques have been proposed, and are mainly based on IHC. Very few of these techniques have been used routinely, and nowadays HCV RNA quantitation by means of RT-PCR has largely replaced IHC for HCV in most laboratories. Indeed, albeit more expensive, RT-PCR is by far more sensitive and specific than IHC, and can be of great help in the early post-OLT management of recipients, even if RT-PCR itself is likely to be replaced in the future by some new technologies (not included in the present review). An open question is whether RT-PCR might be useful in the long post-OLT term, i.e., if HCV RNA intrahepatic viral load after 1 year or more might have a prognostic meaning, for example in predicting fibrosis progression, or if other factors prevail, such as the host immune system, HSC activation, etc. Future prospective studies with an adequate follow-up are surely required. Protocol biopsies represent another important issue: without doubt they are very useful in the study of allograft disease progression, but they are not free from complications and might not be accepted by patients. It is likely that each transplant team will formulate its policy for post-transplant biopsies in the future, since arguments exist both in support of and against protocol biopsies.

There is no doubt that protocol biopsies will be indispensable in answering other open questions, such as the significance of plasma cell infiltrate in HCV-positive allografts, the real prognostic weight of HCV-induced graft steatosis, and the impact of donor age and graft characteristics in recurrent hepatitis C.

P- Reviewers: Gruttadauria S, Hanazaki K, Pan JJ S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Ma S