Published online Mar 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2681

Revised: December 18, 2013

Accepted: January 8, 2014

Published online: March 14, 2014

Processing time: 253 Days and 1.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate feasibility of the novel forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope for staging of colon cancer beyond rectum as the first series.

METHODS: A retrospective study with prospectively entered database. From March 2012 to February 2013, a total of 21 patients (11 men) (mean age 64.2 years) with colon cancer beyond the rectum were recruited. The novel forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope was used for ultrasonographic staging of colon cancer beyond rectum. Ultrasonographic T and N staging were recorded when surgical pathology was used as a gold standard.

RESULTS: The mean time to reach the lesion and the mean time to complete the procedure were 3.5 and 7.1 min, respectively. The echoendoscope passed through the lesions in 13 patients (61.9%) and reached the cecum in 10 of 13 patients (76.9%). No adverse events were found. The lesions were located in the cecum (n = 2), ascending colon (n = 1), transverse colon (n = 2), descending colon (n = 2), and sigmoid colon (n = 14). The accuracy rate for T1 (n = 3), T2 (n = 4), T3 (n = 13) and T4 (n = 1) were 100%, 60.0%, 84.6% and 100%, respectively. The overall accuracy rates for the T and N staging of colon cancer were 81.0% and 52.4%, respectively. The accuracy rates among traversable lesions (n = 13) and obstructive lesions (n = 8) were 61.5% and 100%, respectively. Endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography had overall accuracy rates of 81.0% and 68.4%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: The echoendoscope is a feasible staging tool for colon cancer beyond rectum. However, accuracy of the echoendoscope needs to be verified by larger systematic studies.

Core tip: Endoscopic ultrasound staging of rectal cancer has higher accuracy rate than computed tomography (CT) scan. Unfortunately, with the current design of conventional oblique-viewing radial-array echoendoscope that cannot readily be introduced beyond rectum, staging of colon cancer beyond rectum nowadays depends on results of CT scan. With a design of the novel forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope that can be easily passed through the entire colon, it was firstly used in this study for staging of colon cancer. The study showed feasibility of the scope and its superiority over CT scan in terms of accuracy rate of colon cancer staging.

- Citation: Kongkam P, Linlawan S, Aniwan S, Lakananurak N, Khemnark S, Sahakitrungruang C, Pattanaarun J, Khomvilai S, Wisedopas N, Ridtitid W, Bhutani MS, Kullavanijaya P, Rerknimitr R. Forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope for staging of colon cancer beyond the rectum. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(10): 2681-2687

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i10/2681.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2681

Preoperative colon and rectal cancer staging are the main factors in determining the subsequent treatment modality for patients with these types of cancer. Accurate preoperative staging is crucial, as it can greatly influence the results[1]. For rectal cancer, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) demonstrates a higher accuracy of T and N staging compared to computed tomography (CT). Hence, EUS, rather than CT, was suggested as the staging tool of choice for rectal cancer, and it has had a significant impact on the management of rectal cancer[2]. Consequently, we speculated that if EUS can stage colon cancer beyond the rectum, it may yield more accurate results than CT and may improve the outcomes for colon cancer. Unfortunately, with the current design of EUS, it is not possible to use the EUS to stage colon cancer beyond the rectum. Through the scope, a miniprobe can be used to stage colon cancer; however, only a few studies thus far have reported its accuracy rate. Although it has been used for this purpose for over a decade, the supporting data are not well established[3].

The current radial-array EUS has a limited oblique endoscopic view that precludes deep intubation of the EUS probe into the colon beyond the rectum. With the new design of a forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope [radial Scan Ultrasonic Video Endoscope EG-530UR2 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Ultrasound Processor SU-8000 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)], the scope can readily pass to the cecum to locally stage colon cancer. We pioneered this procedure and initiated this study to report the feasibility and accuracy of the new scope in the T staging of colon cancer, using surgical pathology as a gold standard.

From March 2012 to February 2013, patients with colon cancer beyond the rectum identified by colonoscopy in King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand were eligible for this study. The inclusion criteria included patients aged 18-80 years with colon cancer and with an endoscopic or surgical resection scheduled within 4 wk. The exclusion criteria included patients with contraindications for surgery and/or EUS examination of the colon. The recruited patients were examined by colon EUS with a radial-array echoendoscope [radial Scan Ultrasonic Video Endoscope EG-530UR2 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and an Ultrasound Processor SU-8000 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)]. The risks and benefits of the procedure were described to the patients before the operation. The study protocol was approved by our university institutional review board as a retrospective study with prospectively entered database. The study was funded by King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital and faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Demographic data, including gender, age, and symptoms at presentation, were recorded. The endoscopic and EUS data, including the location of the lesion, the percent of circumferential involvement, the duration of the procedure, endoscopic findings, EUS findings, extent of tumor invasion, and the ability to pass the echoendoscope through the lesion, were also recorded. Ultrasonographic T staging was determined and recorded onsite by the endosonographer of the hospital (P.Kongkam). He was blinded to CT results prior to the procedure, as the results of the pre-procedural T stage would influence his judgments. The patients were sedated with conscious sedation (Meperidine and Midazolam) during procedures. Next, the patients were postoperatively observed in the recovery room according to the standard protocol for the endoscopy. After the procedure, the patients were followed up postoperatively by a physician on the team (S.L.). Any adverse events that arose during the procedure were noted. The clinical follow-up to detect any procedure-related adverse event was finished before any subsequent endoscopic or surgical removal. Within the next 4 wk, endoscopic or surgical resection was subsequently performed, and the surgical specimens were examined and pathologically T staged. The surgical pathological T stage was used as the gold standard against which the EUS T stage was compared. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy were also calculated for each pathological T stage.

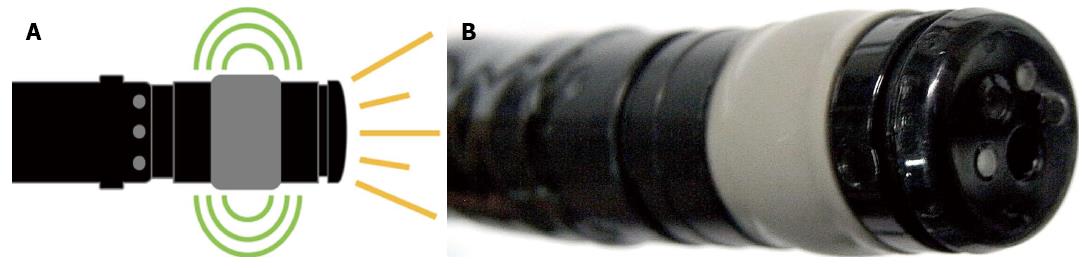

The forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope [radial Scan Ultrasonic Video Endoscope EG-530UR2 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Ultrasound Processor SU-8000 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)] is a newly designed echoendoscope that provides a forward endoscopic view similar to that of a regular forward-viewing endoscope (Figure 1). Ultrasound waves were distributed perpendicularly to the tip of the echoendoscope, as in a regular radial echoendoscope. The frequencies included 5, 7.5, 10 and 12 MHz. In our study, we typically used 12 MHz for the staging of the tumor, as it was considered the optimal frequency to provide the best endosonographic imaging; however, the frequency was adjusted from 5 to 12 MHz to acquire the finest image. Theoretically, a lower frequency should provide farther endosonographic images, whereas a higher frequency should provide nearer images. All equipment was packaged in the format of a one-cart system. The echoendoscope had a small outer diameter of 11.4 mm with a forward endoscopic view of 140° and measured 120 cm in length.

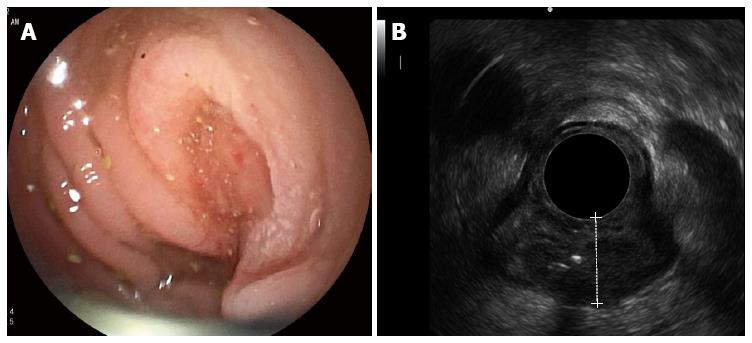

Inserting the echoendoscope into the colon utilized the same maneuver as that used in the standard colonoscopy technique. However, because the echoendoscope was shorter than the regular colonoscope, the use of endoscopic techniques, such as pulling and shortening the scope, was encouraged. To illustrate the endosonographic images, water immersion was used to create an optimal endosonographic view for the staging of colon cancer. Water was not necessary if the endosonographic view was sufficient for staging. The balloon was not used to illustrate the endosonographic images. If the echoendoscope could pass through the lesions, it was placed in the middle of the lesion to most effectively stage the cancer. Nonetheless, if the echoendoscope could not be passed through the lesion, the stage was decided by the endosonographer at the location he deemed optimal. Figure 2A and B demonstrate the endoscopic and endosonographic images of malignant masses in the sigmoid colon. The lesion was endosonographically and pathologically staged as T3.

During the study time, 82 patients with colon cancer located beyond rectum underwent colectomy. Twenty-one patients (25.6%) were recruited into the study. Eleven of them were male, and the mean age was 64.2 years (SD = 11.91), ranging from 43 to 85 years old. The presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (n = 9), weight loss (n = 8), hematochezia (n = 3), melena (n = 4), anemic symptoms (n = 5), bowel habit changes (n = 13), small caliber of stool (n = 7), partial gut obstruction (n = 4) and complete gut obstruction (n = 2). A positive family history of colon cancer was found in 2 patients. Distant metastasis at the time of the EUS procedure was evident in 1 patient.

The mean time to reach the lesion was 3.52 min (SD = 2.09), and the mean procedural time was 7.10 min (SD = 1.41). The echoendoscope could pass through the lesions in 13 patients (61.9%). Among these, the echoendoscope reached the cecum in 10 patients (76.9%). The mean depth of the echoendoscope before reaching the lesions was 44.39 cm (SD = 27.21). No adverse events were found. The median duration from the date of EUS to surgery was 7 d (range from 1-40 d), and lesions were located in the cecum (n = 2), ascending colon (n = 1), transverse colon (n = 2), descending colon (n = 2), and sigmoid colon (n = 14).

The tumors were pathologically staged as T1 (n = 3), T2 (n = 4), T3 (n = 13) and T4 (n = 1). The ultrasonographic T stagings were T1 (n = 2), T2 (n = 5), T3 (n = 13) and T4 (n = 1), as shown in Table 1. The overall accuracy rates of the echoendoscope for the T and N staging of colon cancer were 81.0% and 52.4%, respectively. The accuracy rates for T1, T2, T3 and T4 were 100%, 60.0%, 84.6% and 100%, respectively, as shown in Table 2. The accuracy rates among the traversable lesions (n = 13) and obstructive lesions (n = 8) were 61.5% and 100%, respectively. In comparison with other radiological imaging modalities, EUS and CT had overall accuracy rates of 81.0% and 68.4%, respectively (the data for CT were not available in 2 patients). The results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

| EUS/Histology | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | Total |

| uT1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| uT2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| uT3 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 13 |

| uT4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 3 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 21 |

| Pathological stage | T1/T2 | T3/T4 | Total |

| EUS (n = 21) | 5 | 12 | 17 |

| CT (n = 19) | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Modality | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy |

| EUS (n = 21 ) | 85.0% | - | 94.4% | - | 80.9% |

| CT scan (n = 19) | 76.5% | - | 86.7% | - | 68.4% |

The current echoendoscope provides an oblique endoscopic view. This makes passing an echo-endoscope through the sigmoid colon impossible or significantly limited, as this part of colon is redundant and any scope with oblique viewing could not easily pass through it. Currently, only 3 types of echoendoscope can readily pass through the sigmoid colon: the miniprobe echoendoscope, the forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope, and the forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope, which was used in this study. While some studies use the first two types of echoendoscope to evaluate lesions in the colon beyond the rectum, this study utilized the forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope, making us among the first in the world to assess its efficacy in evaluating and staging colon cancer in the colon far beyond the rectum. Bhutani et al[4] previously used a forward-oblique-viewing upper echoendoscope for T staging of sigmoid/left colon cancer and reported high accuracy rate. However, with the design of forward-oblique-viewing, it is not practical to pass it far beyond the rectum.

The physical properties of the first two echoendoscopes result in limitations in their capacity to stage colon cancer. For the miniprobe echoendoscope, the scope is so small that it can be inserted through the biopsy channel of the regular colonoscope. This allows the scope to pass through the entire colon. Therefore, this type of echoendoscope has been used to evaluate colon cancer in some studies[5]. A large German study prospectively recruited 50 patients with colonic tumors. Lesions were correctly classified in 17 adenomas: 16 T1, 8 T2, 5 T3 and 1 T4 cases of colon cancer. The total accuracy rate for T staging was 94%[6]. Considering the high accuracy rate of T staging with the miniprobe in colon cancer, this technique should be recommended as the tool of choice for staging colon cancer. However, in the German study, patients with locally advanced colon cancer were excluded, as the recruited patients were primarily referred for laparoscopic surgical removal. In addition, the majority of lesions were adenoma, not cancer. Therefore, the accuracy rate of 94% from the German study could not be directly compared with that in our study[6]. Another study from Germany of 88 patients with colon tumors reported an accuracy rate of 87%; however, similar to the prior study, 25 of the 88 patients had adenoma (T0), with an accuracy rate of 100%. Therefore, the reported accuracy rate once again could not be directly compared with that of the current study[7]. A small study using a miniprobe involving 17 and 13 patients with colon and rectal cancer, respectively, reported an accuracy of 70%[8]. Another study used the miniprobe to detect residual disease in malignant polyps, 12 of which were intra-mucosal and 9 of which were sub-mucosal. The results showed that the surgical pathology was free of cancer in 6 patients with normal endosonographic findings who underwent surgery[9]. In conclusion, the range of sound waves used by the miniprobe was too shallow to examine all of the layers of the colonic wall, particularly in advanced stages of cancer that infiltrate into the deeper colonic wall, leading to a much thicker colonic wall[10]. Therefore, it is considered unsuitable for colon cancer staging, particularly in cases of locally advanced colon cancer. In other cases, the results from past studies, including the above, showed that miniprobes, particularly those with high frequencies, are more suitable for the evaluation of early stages of colon cancer, classified as T1/T2[11-14].

The forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope provides a front endoscopic view, allowing the echoendoscope to be readily passed to the cecum, according to the standard techniques for colonoscopy. However, because the sound wave was distributed in a linear direction, this technique is not suitable to evaluate circumferential lesions, such as colon cancer. In a feasibility study that used the forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope in 15 patients with right side colonic sub-epithelial lesions, it was reported that the cecum was reached within 10 min in all patients. FNA was performed in 6 patients without any post-procedural adverse events[15]. This echoendoscope was then used to perform FNA from extra-colonic lesions. A study using a forward-oblique-viewing upper echoendoscope for the evaluation of 32 benign and malignant lesions reported an 85% accuracy rate for T staging in 20 patients with available surgical pathologies[4]. Another recent study reported data from the forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope for an evaluation of 23 sub-epithelial lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. In 6 patients with colonic lesions, the echoendoscope could not reach the cecum in 1 patient[16]. This study, to our knowledge, is the first study in the world using the novel forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope for colon cancer staging. The front endoscopic view makes the procedure’s technique nearly the same as that used in standard colonoscopy, as it provides a similar endoscopic view, and the scopes have similar diameters. At present, a radial-array sound wave is suitable for the evaluation of circumferential lesions, as in colon cancer. Moreover, a wide range of wavelengths allows the echoendoscope to scan the extra-colonic area to search for any surrounding lymph node. The results from this study show that, in all patients, the lesions were reached without any adverse event. The time to reach the lesions was similar to that in standard colonoscopy techniques. This suggests that the forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope [radial Scan Ultrasonic Video Endoscope EG-530UR2 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)] and Ultrasound Processor SU-8000 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) can be used safely as the staging tool of choice for colon cancer. The advantages and disadvantages of these 3 types of echoendoscope are compared and shown in Table 4.

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| A miniprobe echoendoscope | Widely available Can be used together with regular colonoscope | Cannot be properly used for evaluation of thickened-wall colon cancer |

| A forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope | Ability to perform EUS guided fine needle aspiration for colonic lesions | Inconvenient to evaluate circumferential colonic lesions like colon cancer |

| A forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope | Ability to evaluate circumferential colonic lesions | Inability to perform EUS guided FNA for colonic lesions |

The preoperative T staging of rectal cancer can be accurately performed by trans-rectal EUS and or MRI[10,17-20]. A recent meta-analysis of 42 studies (n = 5039) using trans-rectal EUS for the staging of rectal cancer showed that the sensitivity and specificity rates of T1, T2, T3, and T4 were 87.8% and 98.3%, 80.5% and 95.6%, 96.4% and 90.6%, and 95.4 and 98.3%, respectively[21]. Based on the results of this meta-analysis, the accuracy rate of T2 tumors was the lowest. This was a common finding from the recruited studies in this meta-analysis. Similar trend was observed in our study. Our results suggested that the new type of EUS for the staging of colon cancers beyond the rectum provided an acceptable accuracy rate for T staging; however, it had a relatively low accuracy rate for N staging. Although surgical pathology was available for calculation in all of the cases in this series, the accuracy of this procedure from this study should not be consider conclusive, as the number of cases was too small. Furthermore, as the first study to use the echoendoscope to stage colon cancer, the learning curve could have reduced the accuracy of colon cancer staging. Future studies with a greater number of patients are thus required to definitively determine the accuracy of EUS for the T and N staging of colon cancer. The number of patients in future studies can be calculated based on the data from this study. As N staging significantly impacts the management of these cancers, further studies to clarify these answers are strongly needed.

An accurate preoperative staging of rectal cancer by trans-rectal EUS influences definitive management. For example, T1/T2 rectal cancer can be managed with either endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection, with a 5-year survival rate higher than 90%, whereas T3/T4 cancers should be removed with surgery[22-24]. For colon cancer, the data from the pilot phase of a recent randomized controlled trial (The FOxTROT trial) suggested that neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced operable colon cancer significantly decreased TNM staging, compared with the postoperative group[25]. Therefore, if EUS was proven to be the most reliable tool for preoperative colon cancer staging, it should be combined with clinical practice before a decision is made to offer specific treatment to patients. CT data for the staging of colon cancer from a multi-center study in the UK showed that when CT was used for differentiation between early (T1/T2) and advanced stages of colon cancer, the sensitivity and specificity rates were 95% (95%CI: 87%-98%) and 50% (95%CI: 22%-77%), respectively[26]. The data from our study, despite the small number of patients, suggest that accuracy rate of EUS is clearly higher than that of CT scans, which are currently the tool of choice for staging colon cancer. In addition, with the current design of this new echoendoscope, it may be used in the future as a standard colonoscope for patients who have suspicious symptoms of colon cancer, as endoscopists can perform colonoscopy, tissue biopsy and endosonographic staging in the same procedure without the significant technical differences or adverse events from standard colonoscopy.

This study demonstrated that the forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope is a feasible technique for staging colon cancer. The success and adverse event rates were low and similar to those of standard colonoscopy. However, systematic and larger studies with more patients must be conducted to specify the accuracy of the echoendoscope for this purpose.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), rather than computed tomography (CT), was suggested as the staging tool of choice for rectal cancer as it demonstrates a higher accuracy of T and N staging compared to CT. Consequently, the authors speculated that if EUS can stage colon cancer beyond the rectum, it may yield more accurate results than CT and may improve the outcomes for colon cancer. Unfortunately, with the current design of EUS, it is not possible to use the EUS to stage colon cancer beyond the rectum.

The current echoendoscope provides an oblique endoscopic view. This makes passing an echo-endoscope through the sigmoid colon impossible, as this part of colon is redundant and any scope with oblique viewing could not pass through it. Currently, only 3 types of echoendoscope can pass through the sigmoid colon: the miniprobe echoendoscope, the forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope, and the forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope, which was used in this study. While some studies use the first two types of echoendoscope to evaluate lesions in the colon beyond the rectum, this study utilized the forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope, making the authors among the first in the world to assess its efficacy in evaluating and staging colon cancer in the colon beyond the rectum. The physical properties of the first two echoendoscopes result in limitations in their capacity to stage colon cancer. For the miniprobe echoendoscope, the scope is so small that it can be inserted through the biopsy channel of the regular colonoscope. This allows the scope to pass through the entire colon. However, the range of sound waves used by the miniprobe was too shallow to examine all of the layers of the colonic wall, particularly in advanced stages of cancer that infiltrate into the deeper colonic wall, leading to a much thicker colonic wall. Therefore, it is considered unsuitable for colon cancer staging, particularly in cases of locally advanced colon cancer. The forward-viewing linear-array echoendoscope provides a front endoscopic view, allowing the echoendoscope to be readily passed to the cecum, according to the standard techniques for colonoscopy. However, because the sound wave was distributed in a linear direction, this technique is hence not suitable to evaluate circumferential lesions, such as colon cancer.

The forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope [radial Scan Ultrasonic Video Endoscope EG-530UR2 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Ultrasound Processor SU-8000 (FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)] is a newly designed echoendoscope that provides a forward endoscopic view similar to that of a regular forward-viewing endoscope. Ultrasound waves were distributed perpendicularly to the tip of the echoendoscope, as in a regular radial echoendoscope. All equipment was packaged in the format of a one-cart system. The echoendoscope had a small outer diameter of 11.4 mm with a forward endoscopic view of 140° and measured 120 cm in length. Inserting the echoendoscope into the colon utilized the same maneuver as that used in the standard colonoscopy technique. The novel forward-viewing radial-array echoendoscope can be readily passed through the colon.

In this study, EUS was proven to be the most reliable tool for preoperative colon cancer staging. It hence should be combined with clinical practice before a decision is made to offer specific treatment to patients particularly in patients with locally advanced operable colon cancer.

Twenty-one colon cancers enrolled in 11 mo looks not really a relevant number. Authors should clarify their hospital volume (number of colectomies performed for cancer and number of standard endoscopies performed for cancer each year). Moreover, even though authors declared to have calculate the sensitivy, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value of the EUS and of the standard radiology, the show exclusively the accuracy results.

P- Reviewers: Chisthi MM, El-TawilAM, Lorenzon L S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Bhutani MS. Endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis, staging and management of colorectal tumors. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:215-217, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, Maccarty RL, Olson JE, Clain JE, Ahlquist DA, Jondal ML. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:24-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schizas AM, Williams AB, Meenan J. Endosonographic staging of lower intestinal malignancy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:663-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bhutani MS, Nadella P. Utility of an upper echoendoscope for endoscopic ultrasonography of malignant and benign conditions of the sigmoid/left colon and the rectum. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3318-3322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gall TM, Markar SR, Jackson D, Haji A, Faiz O. Mini-probe ultrasonography for the staging of colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:O1-O8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stergiou N, Haji-Kermani N, Schneider C, Menke D, Köckerling F, Wehrmann T. Staging of colonic neoplasms by colonoscopic miniprobe ultrasonography. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hünerbein M, Handke T, Ulmer C, Schlag PM. Impact of miniprobe ultrasonography on planning of minimally invasive surgery for gastric and colonic tumors. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:601-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chung HW, Chung JB, Park SW, Song SY, Kang JK, Park CI. Comparison of hydrocolonic sonograpy accuracy in preoperative staging between colon and rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1157-1161. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Haji A, Ryan S, Bjarnason I, Papagrigoriadis S. High-frequency mini-probe ultrasound as a useful adjunct in the management of patients with malignant colorectal polyps. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rafaelsen SR, Vagn-Hansen C, Sørensen T, Pløen J, Jakobsen A. Transrectal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging measurement of extramural tumor spread in rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5021-5026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hurlstone DP, Brown S, Cross SS, Shorthouse AJ, Sanders DS. High magnification chromoscopic colonoscopy or high frequency 20 MHz mini probe endoscopic ultrasound staging for early colorectal neoplasia: a comparative prospective analysis. Gut. 2005;54:1585-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kauer WK, Prantl L, Dittler HJ, Siewert JR. The value of endosonographic rectal carcinoma staging in routine diagnostics: a 10-year analysis. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1075-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tsung PC, Park JH, Kim YS, Kim SY, Park WW, Kim HT, Kim JN, Kang YK, Moon JS. Miniprobe endoscopic ultrasonography has limitations in determining the T stage in early colorectal cancer. Gut Liver. 2013;7:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Urban O, Kliment M, Fojtik P, Falt P, Orhalmi J, Vitek P, Holeczy P. High-frequency ultrasound probe sonography staging for colorectal neoplasia with superficial morphology: its utility and impact on patient management. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3393-3399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nguyen-Tang T, Shah JN, Sanchez-Yague A, Binmoeller KF. Use of the front-view forward-array echoendoscope to evaluate right colonic subepithelial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:606-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Diehl DL, Johal AS, Nguyen VN, Hashem HJ. Use of a forward-viewing echoendoscope for evaluation of GI submucosal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:428-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Swartling T, Kälebo P, Derwinger K, Gustavsson B, Kurlberg G. Stage and size using magnetic resonance imaging and endosonography in neoadjuvantly-treated rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3263-3271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mezzi G, Arcidiacono PG, Carrara S, Perri F, Petrone MC, De Cobelli F, Gusmini S, Staudacher C, Del Maschio A, Testoni PA. Endoscopic ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging for re-staging rectal cancer after radiotherapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5563-5567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, Zippel R, Kuhn R, Wolff S, Pross M, Wierth A, Gastinger I, Lippert H. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34:385-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fernández-Esparrach G, Ayuso-Colella JR, Sendino O, Pagés M, Cuatrecasas M, Pellisé M, Maurel J, Ayuso-Colella C, González-Suárez B, Llach J. EUS and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer: a prospective and comparative study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:347-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:254-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kav T, Bayraktar Y. How useful is rectal endosonography in the staging of rectal cancer? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:691-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Meredith KL, Hoffe SE, Shibata D. The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2009;89:177-215, ix-x. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Giovannini M, Ardizzone S. Anorectal ultrasound for neoplastic and inflammatory lesions. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:113-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Foxtrot Collaborative Group. Feasibility of preoperative chemotherapy for locally advanced, operable colon cancer: the pilot phase of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1152-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dighe S, Swift I, Magill L, Handley K, Gray R, Quirke P, Morton D, Seymour M, Warren B, Brown G. Accuracy of radiological staging in identifying high-risk colon cancer patients suitable for neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a multicentre experience. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:438-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |