Published online Dec 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9063

Revised: September 12, 2013

Accepted: September 29, 2013

Published online: December 21, 2013

Processing time: 183 Days and 6.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate seasonal variations in the onset and relapse of ulcerative colitis (UC) in Japanese patients.

METHODS: Between 1994 and 2006, 198 Japanese patients diagnosed with UC according to conventional criteria in an academic hospital were enrolled for onset evaluation. Among 265 Japanese patients with UC who were observed for more than 12 mo, 165 patients relapsed (239 times) and were enrolled for relapse evaluation. The patients’ symptoms were recorded each month for 12 consecutive years.

RESULTS: There was monthly seasonality in symptom onset during October and March for UC. The onset of symptoms in UC patients frequently occurred during the winter. Variation in UC onset was observed according to both month (P = 0.015) and season (P = 0.048). Relapse commonly occurred in October, and variations in relapse were not significant either in month (P = 0.52) or season (P = 0.12). Upper respiratory inflammation was the main factor responsible for relapse.

CONCLUSION: Our results suggest that environmental factors associated with winter and spring seasonality may be responsible for triggering the clinical onset of UC in Japan.

Core tip: Monthly seasonality in the symptomatic onset of ulcerative colitis (UC) during October and March was observed in Japan. The onset of symptoms frequently occurred during the winter, whereas relapse of UC particularly occurred in October. Upper respiratory inflammation was one of the main factors responsible for relapse. Therefore, environmental factors associated with winter and spring seasonality may be responsible for triggering the clinical onset of UC in Japan.

- Citation: Koido S, Ohkusa T, Saito H, Yokoyama T, Shibuya T, Sakamoto N, Uchiyama K, Arakawa H, Osada T, Nagahara A, Watanabe S, Tajiri H. Seasonal variations in the onset of ulcerative colitis in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(47): 9063-9068

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i47/9063.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9063

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic relapsing disease characterized by alternating periods of remission and active disease. UC is the result of a complex interaction between genetic susceptibility[1], stimulation by bacterial antigens[2] in the lumen and occasional environmental triggers[3] that damage the mucosal barrier. Although the incidence and prevalence of UC is lower in Asia than in the West, recent population-based and referral center cohorts have shown a rising incidence and prevalence of UC in Asia[3]. Therefore, it is critical to gain a better understanding of the environmental factors that contribute to the onset and relapse of UC in Asia.

Furthermore, the environmental factors associated with UC are poorly defined. For example, previous studies examining seasonal variations in the onset and relapse of UC in Western populations[4-10] have demonstrated conflicting results. These studies used retrospectively collected or hospital admission data, which may have led to a bias in the results. Moreover, due to different cultural backgrounds, racial genetic predisposition and dietary habits, Japanese patients may show different clinical patterns from those of Western populations. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate whether there were seasonal variations in the onset and relapse of symptoms in Japanese patients with UC.

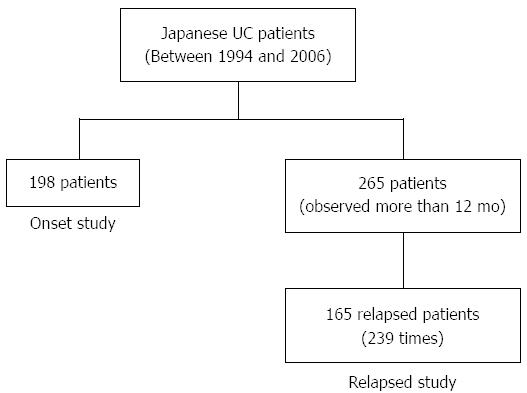

We performed an epidemiological cohort study of Japanese patients with UC who were diagnosed according to conventional criteria[11] between 1994 and 2006 at an academic hospital in Tokyo. The diagnosis of UC was confirmed by a typical history combined with the appropriate endoscopic, histopathological, and radiologic findings[11]. A total of 198 patients were enrolled in the onset evaluation (Figure 1). Data concerning the onset of symptoms were prospectively assessed using a standard interview focusing on symptoms accepted for UC (diarrhea, blood in stool, mucus or pus in stool, abdominal pain, fever, weight loss) and the period of time in which such symptoms occurred for the first time. The date of diagnosis was established according to the first investigation (endoscopy and histology, radiology or surgery) in which a diagnosis of UC could be defined. The onset of symptoms was recorded each month for 12 consecutive years. Relapse was defined as 3 or more increases in the symptom score[12], excluding patients who relapsed due to decreasing doses of steroids, 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), or salazosulfapyridine (SASP).

Among 265 Japanese patients with UC observed for more than 12 mo between 1994 and 2006, 165 patients relapsed (239 times). The symptom scores of these patients were recorded each month for at least one year (Figure 1). The frequencies of onset and relapse were compared for each month and the following four seasons: winter (December to February), spring (March to May), summer (June to August), and autumn (September to November).

The frequencies of onset and relapse were compared using the χ2 test. In addition, the 12-mo seasonality was tested using Rogers’ method. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

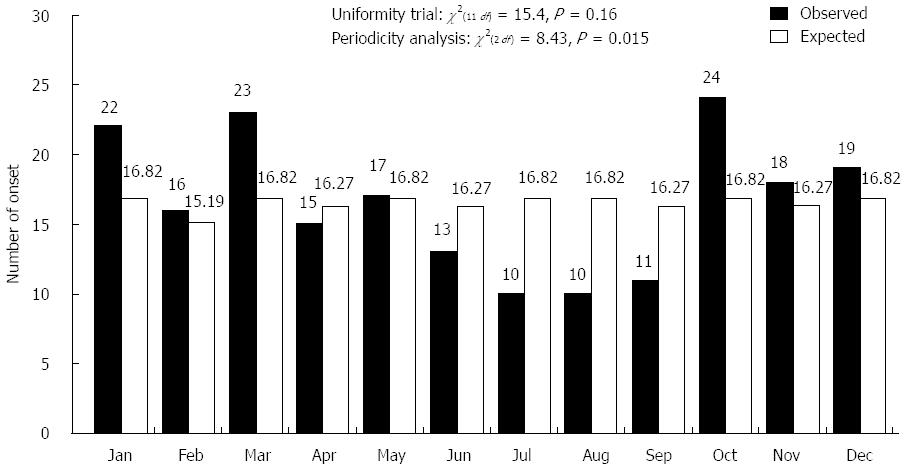

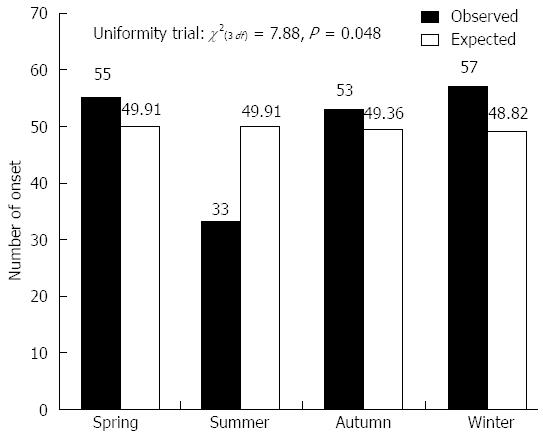

A total of 198 Japanese patients with UC (132 males and 66 females) were investigated in the onset evaluation. The median age at diagnosis was 35 ± 14 years. The distribution of symptom onset according to month is shown in Figure 2. The timing of symptom onset was characterized by a clear monthly variation (χ2(2 df) = 8.43, P = 0.015), with a peak during October and March and a trough during June and September. Moreover, a seasonal pattern was observed (χ2(3 df) = 7.88, P = 0.048), as the onset rate was highest from autumn to spring [observed/expected (O/E): 53/49.36, 57/48.82, 55/49.91, respectively] (Figure 3).

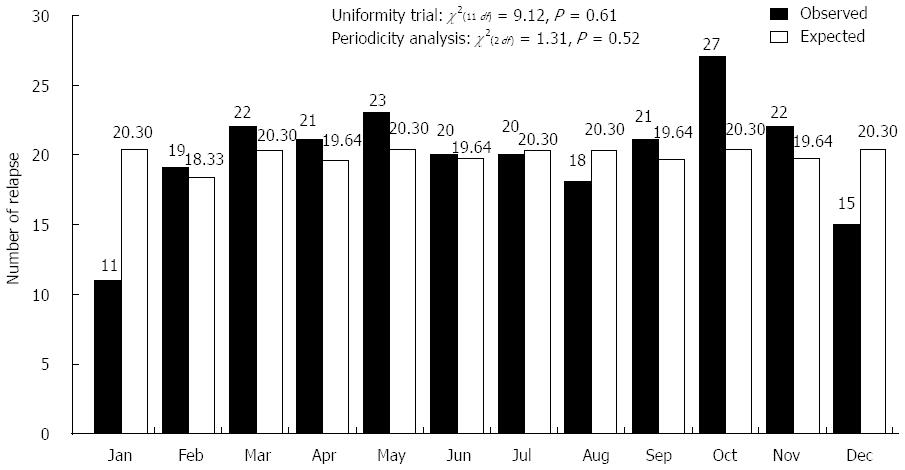

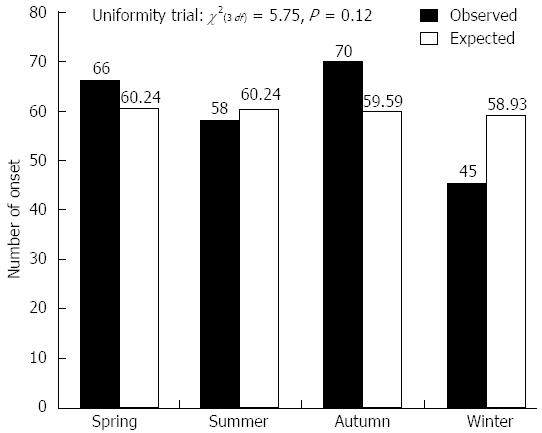

Among 265 Japanese patients with UC observed for more than 12 mo, 165 patients relapsed (239 times), which was defined as 3 or more increases in the symptom score[12]. Patients who relapsed due to decreasing doses of steroids, 5-ASA, or SASP were excluded. The median age at relapse was 34 ± 12 years. Figure 4 shows the 165 observed UC patients according to month, taking into consideration the difference in the number of UC relapses each month. Relapse of symptoms in UC patients frequently occurred in October (O/E: 27/20.30). The lowest relapse rate was observed in January (O/E: 11/20.30). Variations in relapse were not found on a monthly basis (χ2(2 df) = 1.31, P = 0.52, Figure 4). Moreover, there was no variation in relapse on a seasonal basis (χ2(3 df) = 5.75, P = 0.12) (Figure 5).

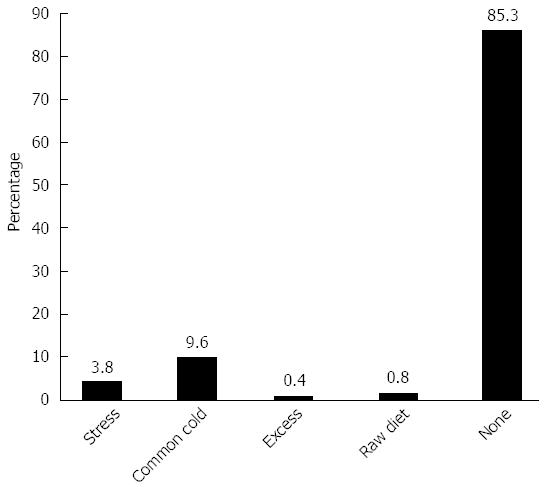

In most cases, the causes of relapse were not identified. However, in cases with an identifiable cause, upper respiratory inflammation was the main factor responsible for relapse (Figure 6).

It is well known that environmental factors contribute to the induction of UC, although little is known about the relationship between seasonality and symptom flares in Asian UC patients, especially in the Japanese population. Therefore, we performed an epidemiological cohort study of patients with UC diagnosed between 1994 and 2006 at an academic hospital in Tokyo. The diagnosis of UC was confirmed by a typical history combined with the appropriate endoscopic, histopathological, and radiologic findings[11]. A total of 198 patients (132 males and 66 females) were enrolled in the onset evaluation.

A growing number of studies in Asia have reported an equal gender distribution in UC[12], although several studies have also demonstrated a male predominance[13]. In our academic hospital-based cross sectional study, there was a preponderance of male UC cases. These conflicting findings may, at least in part, reflect the small population numbers in the present study. Our results revealed seasonal variations in the onset of UC symptoms in Japanese patients, although there was no difference in the timing of relapse. We observed monthly seasonality in the symptomatic onset of UC in October and March, mainly in winter and spring. Previous studies have reported seasonal variations in the symptomatic onset of UC in December in the United Kingdom[5,14], December to January in Norway[15], and June to August in Spain[16]. Moreover, increased relapse rates for UC were reported in winter[4] and autumn[5] in the United Kingdom, spring to autumn in Greece[8], and winter in Sweden[7]; however, other studies reported no seasonality in the United Kingdom[17], Spain[16], or the United States[10,18]. These conflicting data may, at least in part, reflect the distinct genetic backgrounds of the study populations. In addition, the different seasonal patterns observed in different countries could also reflect variations in the climate and related environmental triggering factors associated with the onset of UC.

The environmental factors that may induce the onset or relapse of UC are not well understood. Patients with UC often experience exacerbations following bacterial and viral infections, and it is interesting that enteric pathogens such as Salmonella, Campylobacter, E. coli, and Clostridium difficile may cause relapses in UC. We have also reported that bacteria such as Fusobacterium varium (F. varium) can modulate the gut immune response and contribute to UC[19]; however, F. varium infections do not show a seasonal pattern of occurrence. Smoking is a well-known environmental factor for UC[20], and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)[21] and antibiotics[22] is also a risk factor for UC. In particular, during the winter, due to respiratory tract infections with organisms such as influenza and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, these drugs may be associated with the onset of UC. It has also been reported that respiratory and systemic viral infections are associated with the exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease[23,24]. Also during the winter, intake of NSAIDs due to arthritic pain is common in Japan. In this study, cigarette smoking was not found to enhance the onset of UC, which is in contrast to previous reports concerning Crohn’s disease[25]. Normally, patients with UC experience exacerbation when they attempt to quit smoking[25]. Cigarette smoking may especially enhance the onset of UC in combination with other seasonal environmental factors, such as the intake of NSAIDs and antibiotics in the winter[20], and these variables may explain the high incidence of disease onset observed during the winter. Our data showing that upper respiratory inflammation was the main factor responsible for relapse, with the exception of cases with no apparent cause for relapse, also support the high incidence of UC onset during the winter. Moreover, UC leads to inappropriate immune activation and increased levels of inflammatory cells and mediators, and UC can also be triggered by inappropriate immune activation in genetically predisposed individuals[26]. In addition, seasonal variations in immune responses have been reported[27]; unlike the summer and spring, immune functions and the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are decreased during the winter[28]. These differences in immune function across seasons may also explain the seasonal variations in the onset of UC.

In retrospective studies, UC relapse was shown to occur more frequently in spring and autumn in Western populations[5,8,10]. In our study of Japanese individuals, there were no significant differences in relapse on a monthly or seasonal basis. For most Japanese patients with UC, there may be no clear seasonal trigger for disease relapse, although long-term follow up studies with detailed microbiological surveillance of UC relapse should be performed, as antibiotic therapy can increase susceptibility to bacteria.

In conclusion, our results support the seasonality of UC onset in Japan. We found that the onset of UC in Japan typically occurred between October and March, although relapse rates did not show consistent seasonal variation. However, the present study was an epidemiological cohort study conducted at an academic hospital in Tokyo, and the study size was too small to draw valid statistical conclusions. Therefore, larger studies are needed in a Japanese population to assess the seasonal variations in UC onset and relapse.

The incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis (UC) has increased rapidly in Japan; however, the environmental factors that contribute to the course of UC have not been well defined. Therefore, it is critically important to gain a better understanding of the environmental factors that contribute to the onset and relapse of UC in a Japanese population.

Seasonal variations in the onset or relapse of UC have previously been studied in Western populations with conflicting results. Due to different cultural backgrounds, racial genetic predispositions and dietary habits, Japanese patients may show different clinical patterns from those of Western populations. To date, the environmental factors in Japan have not been well defined, although the results of studies in Western populations suggest that there may be seasonal variation in the natural history of UC.

Environmental factors related to winter and spring seasonality are responsible for triggering the clinical onset of UC in Japan.

The symptomatic onset of UC occurred during October and March in Japan, whereas relapse generally occurred in October. Upper respiratory inflammation was one of the main factors responsible for relapse. Thus, the results of this study shed light on the environmental factors that contribute to the onset and relapse of UC in Japanese patients.

This manuscript reports statistically significant differences in the seasonal variation of UC incidence in a Japanese population. There was monthly seasonality in symptomatic onset during October and March; the onset of symptoms in UC patients generally occurred during the winter. The variation in UC onset was observed for both month (P = 0.015) and season (P = 0.048). In contrast, the variation in relapse was not significant either in month (P = 0.52) or season (P = 0.12). These conclusions support similar previous observations in Western populations.

P- Reviewers: Kaymakoglu S, Nielsen OH, Schofield JB S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Cleynen I, Jüni P, Bekkering GE, Nüesch E, Mendes CT, Schmied S, Wyder S, Kellen E, Villiger PM, Rutgeerts P. Genetic evidence supporting the association of protease and protease inhibitor genes with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ohkusa T, Nomura T, Sato N. The role of bacterial infection in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Intern Med. 2004;43:534-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ananthakrishnan AN. Environmental triggers for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;15:302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Myszor M, Calam J. Seasonality of ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1984;2:522-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Riley SA, Mani V, Goodman MJ, Lucas S. Why do patients with ulcerative colitis relapse? Gut. 1990;31:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sonnenberg A, Wasserman IH. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease among U.S. military veterans. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:122-130. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Tysk C, Järnerot G. Seasonal variation in exacerbations of ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:95-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Karamanolis DG, Delis KC, Papatheodoridis GV, Kalafatis E, Paspatis G, Xourgias VC. Seasonal variation in exacerbations of ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:1334-1338. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Moum B, Aadland E, Ekbom A, Vatn MH. Seasonal variations in the onset of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:376-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lewis JD, Aberra FN, Lichtenstein GR, Bilker WB, Brensinger C, Strom BL. Seasonal variation in flares of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:665-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, Orchard T, Rutter M, Younge L. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1045] [Cited by in RCA: 946] [Article Influence: 67.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1217] [Cited by in RCA: 1174] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujimoto T, Kato J, Nasu J, Kuriyama M, Okada H, Yamamoto H, Mizuno M, Shiratori Y. Change of clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis in Japan: analysis of 844 hospital-based patients from 1981 to 2000. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cave DR, Freedman LS. Seasonal variations in the clinical of presentation of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Int J Epidemiol. 1975;4:317-320. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Moum B, Vatn MH, Ekbom A, Fausa O, Aadland E, Lygren I, Sauar J, Schulz T. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in southeastern Norway: evaluation of methods after 1 year of registration. Southeastern Norway IBD Study Group of Gastroenterologists. Digestion. 1995;56:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vergara M, Fraga X, Casellas F, Bermejo B, Malagelada JR. Seasonal influence in exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1997;89:357-366. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Don BA, Goldacre MJ. Absence of seasonality in emergency hospital admissions for inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet. 1984;2:1156-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Auslander JN, Lieberman DA, Sonnenberg A. Lack of seasonal variation in the endoscopic diagnoses of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2233-2238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ohkusa T, Okayasu I, Ogihara T, Morita K, Ogawa M, Sato N. Induction of experimental ulcerative colitis by Fusobacterium varium isolated from colonic mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2003;52:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lakatos PL, Vegh Z, Lovasz BD, David G, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Szita I, Mester G, Balogh M, Szipocs I. Is current smoking still an important environmental factor in inflammatory bowel diseases? Results from a population-based incident cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1010-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Felder JB, Korelitz BI, Rajapakse R, Schwarz S, Horatagis AP, Gleim G. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1949-1954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fleming DM, Ross AM, Cross KW, Kendall H. The reducing incidence of respiratory tract infection and its relation to antibiotic prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:778-783. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kangro HO, Chong SK, Hardiman A, Heath RB, Walker-Smith JA. A prospective study of viral and mycoplasma infections in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:549-553. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Sonnenberg A. Seasonal variation of enteric infections and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:955-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dietary and other risk factors of ulcerative colitis. A case-control study in Japan. Epidemiology Group of the Research Committee of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Japan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:166-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:514-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 992] [Cited by in RCA: 1003] [Article Influence: 55.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nelson RJ. Seasonal immune function and sickness responses. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Boctor FN, Charmy RA, Cooper EL. Seasonal differences in the rhythmicity of human male and female lymphocyte blastogenic responses. Immunol Invest. 1989;18:775-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |