Published online Dec 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9057

Revised: September 9, 2013

Accepted: September 16, 2013

Published online: December 21, 2013

Processing time: 192 Days and 18.5 Hours

AIM: To assess the reliability and practical applicability of the widely used Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohhmann and Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Appendicitis (RIPASA) scoring systems in patients with suspected acute appendicitis.

METHODS: Patients admitted to our tertiary center due to suspected acute appendicitis constituted the study group. Patients were divided into two groups. appendicitis group (Group A) consisted of patients who underwent appendectomy and were histopathologically diagnosed with acute appendicitis, and non-appendicitis group (Group N-A) consisted of patients who underwent negative appendectomy and were diagnosed with pathologies other than appendicitis and patients that were followed non-operatively. The operative findings for the patients, the additional analyses from follow up of the patients and the results of those analyses were recorded using the follow-up forms.

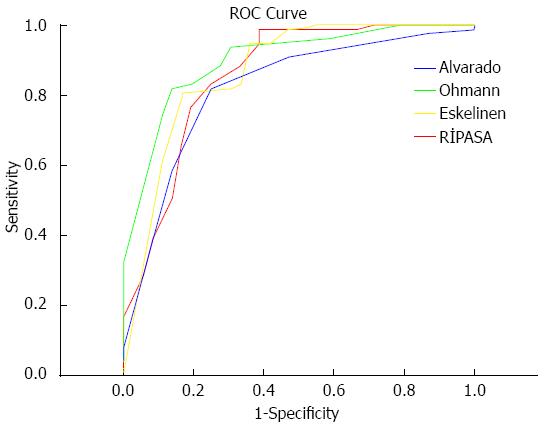

RESULTS: One hundred and thirteen patients with suspected acute appendicitis were included in the study. Of the 113 patients (62 males, 51 females), the mean age was 30.2 ± 10.1 (range 18-67) years. Of the 113 patients, 94 patients underwent surgery, while the rest were followed non-operatively. Of the 94 patients, 77 patients were histopathologically diagnosed with acute appendicitis. Our study showed a sensitivity level of 81% for the Alvarado system when a cut-off value of 6.5 was used, a sensitivity level of 83.1% for the Ohmann system when a cut-off value of 13.75 was used, a sensitivity level of 80.5% for the Eskelinen system when a cut-off value of 63.72 was used, and a sensitivity level of 83.1% for the RIPASA system when a cut-off value of 10.25 was used.

CONCLUSION: The Ohmann and RIPASA scoring systems had the highest specificity for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Core tip: Several scoring systems have been devised to aid decision making in doubtful acute appendicitis cases, including the Ohmann, Alvarado, Eskelinen, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Appendicitis and several others. These scores utilize routine clinical and laboratory assessments and are simple to use in a variety of clinical settings. However, differences in sensitivities and specificities were observed if the scores were applied to various populations and clinical settings, usually with worse performance when applied outside the population in which they were originally created.

- Citation: Erdem H, Çetinkünar S, Daş K, Reyhan E, Değer C, Aziret M, Bozkurt H, Uzun S, Sözen S, İrkörücü O. Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohhmann and Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Appendicitis scores for diagnosis of acute appendicitis. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(47): 9057-9062

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i47/9057.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.9057

Acute appendicitis is a common surgical condition that requires prompt diagnosis to minimize morbidity and avoid serious complications. Accurate identification of patients who require immediate surgery as opposed to those who will benefit from active observation is not always easy[1].

Several scoring systems have been devised to aid decision making in doubtful cases, including the Ohmann, Alvarado, Eskelinen, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Appendicitis (RIPASA) and several others[2-5]. These scoring systems utilize routine clinical and laboratory assessments and are simple to use in a variety of clinical settings. However, differences in sensitivities and specificities were observed if the scores were applied to various populations and clinical settings, usually with worse performance when applied outside the population in which they were originally created[2,3,6]. Additionally, geographic variation of the incidence and clinical pattern of the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain may impair their applicability[7]. Accurate diagnosis of acute appendicitis is especially difficult in women, where the inaccuracy of available diagnostic methods leads to an unacceptably high negative appendectomy rate due to gynecological disorders that frequently mimic appendicitis[8].

This study aimed to assess the reliability and practical applicability of the widely used Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohhmann and RIPASA scoring systems in patients with suspected acute appendicitis.

This prospective study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (ANEAH 2011/2). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Patients admitted to our tertiary center due to suspected acute appendicitis between October 2011 and March 2012 constituted the study group.

Patients were divided into two groups: appendicitis group (Group A) consisted of patients who underwent appendectomy and were histopathologically diagnosed with acute appendicitis, and non-appendicitis group (Group N-A) consisted of patients who underwent negative appendectomy, patients diagnosed to have pathologies other than appendicitis, and patients that were followed non-operatively.

Patient data including age, gender, height, weight, the duration of hospital stay, accompanying disease history, operation or follow-up findings, and laboratory and imaging findings were recorded. Parameters from the Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohmann and RIPASA scoring systems were combined in this form[2-5]. Decisions regarding operation and follow up were given according to the preferences of the surgeon, not the scoring results.

The scores were calculated using an automated Microsoft Excel sheet after the patients were discharged. Calculated values were recorded as having a low, medium or high probability for acute appendicitis (Table 1). Operative findings, additional analyses of follow-up patients and the results of those analyses were recorded using the follow-up forms. A diagnosis of appendicitis was given macroscopically during the operation (purulent formations, and edematous- necrotic changes on the appendix wall). The results were confirmed with histopathological findings.

| High probability | Probable/should be followed | Appendicitis with high probability | |

| Alvarado | < 4 | 5-6 | > 7 |

| Eskelinen | < 48 | 48-57 | > 57 |

| Ohhmann | < 6 | 6-11.5 | > 12 |

| RIPASA | < 5 | 5-7 | > 7.5 |

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and Medcalc (Mariakerke, Belgium) for Windows. The results for all of the items were expressed as the mean ± SD, assessed within a 95% reliance and at a level of P < 0.05 significance. The sample size calculation was based on a significance level of 0.05. We needed a sample of 103 patients to achieve 80% power. A normal distribution of the quantitative data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Parametric tests were applied to the normally distributed data and non-parametric tests were applied to data with a questionably normal distribution. An independent sample t test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare the independent groups. Receiver operating characteristic curves were used to identify the optimal cut-off points. Cross tables were prepared for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and the diagnostic accuracy values of the scoring systems. We used a χ2 test to compare categorical measures regarding the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

One hundred and thirteen patients with suspected acute appendicitis were included in the study. Of the 113 patients (62 males, 51 females), the mean age was 30.2 ± 10.1 (range 18 to 67) years. Of the 113 patients, 94 patients (83.19%) underwent surgery, while the rest (16.81%) were followed non-operatively. Of the 94 patients, 77 patients (81.91%) were histopathologically diagnosed with acute appendicitis, 6 (6.38%) were diagnosed with pathologies other than appendicitis (ovarian cyst rupture in three patients, inflammatory bowel disease in two patients, and a carcinoid tumor in one patient), and 11 patients (11.71%) underwent a negative appendectomy. Among the 19 patients who were followed non-operatively, urinary system disease was diagnosed in eight patients, gastroenteritis was diagnosed in four patients, mesenteric lymphadenitis was diagnosed in one patient, inflammatory bowel disease was diagnosed in one patient and gynecologic problems were diagnosed in one patient. A diagnosis was not established, and clinical improvement was observed in four patients.

Group A included 77 patients (46 males, 31 females) with a mean age of 29.5 ± 9 years, and Group N-A included 36 patients (16 males, 20 females) with a mean age of 31.8 ± 12.1 years. Both groups did not differ significantly in age and gender (P = 0.560 and P = 0.157, respectively). With respect to the mean height (168.9 ± 8.1 cm vs 168.1 ± 8.8 cm), mean weight (71.3 ± 12.8 kg vs 71.6 ± 16.4 kg), and duration of hospital stay (45.3 ± 20.1 d vs 57.9 ± 37.6 d), the two groups were not significantly different (P = 0.634, P = 0.894, and P = 0.065, respectively).

Regarding patient symptoms, there was no similar pain history among the 64 patients that were diagnosed with acute appendicitis, while 13 patients had a similar pain history. It was found that not having a similar pain history was statistically significant for acute appendicitis (P < 0.001). The studied groups differed significantly from each other with regard to the starting point of pain (P = 0.021) and relocalization of the pain to the lower right quadrant (P = 0.020). As for the examination findings, the defense-rigidity, rebound, and Rowsing findings differed significantly between the groups (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P = 0.034, respectively). Fever was also significantly different between the groups (P = 0.015). As for the laboratory results, the neutrophil rate, leukocyte count, and urine analysis results differed significantly between the groups (P = 0.001, P = 0.009, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). The operative and follow-up results for the patients were as follows: phlegmonous in 45 patients, catarrhal in 15 patients, gangrenous in 11 patients, vermiformis (negative appendectomy) in 11 patients, and perforated in six patients.

| Group A | Group N-A | P value | ||

| Symptoms | ||||

| Loss of appetite | Yes | 25 (69) | 66 (86) | 0.072 |

| No | 11 (31) | 11 (14) | ||

| Nausea-Vomiting | Yes | 20 (56) | 52(68) | 0.294 |

| No | 16 (44) | 25 (32) | ||

| Time pain started | < 48 | 21 (58) | 59 (77) | 0.074 |

| > 48 | 15 (42) | 18 (23) | ||

| Starting point of pain | Around stomach | 8 (22) | 37 (48) | 0.021 |

| Lower right quadrant | 25 (69) | 38 (49) | ||

| Anywhere | 3 (8) | 2 (3) | ||

| Relocalization of the pain to the lower right quadrant | Yes | 7 (19) | 33 (43) | 0.020 |

| No | 29 (81) | 44 (57) | ||

| Urinary system complaint | Yes | 9 (25) | 8 (10) | 0.052 |

| No | 27 (75) | 69 (90) | ||

| Similar pain history | Yes | 19 (53) | 13 (17) | < 0.001 |

| No | 17 (47) | 64 (83) | ||

| Findings | ||||

| Sensitivity on lower right quadrant | Yes | 36 (100) | 76 (99) | 0.999 |

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | ||

| Defense-rigidity | Yes | 23 (64) | 77 (100) | < 0.001 |

| No | 13 (36) | 0 (0) | ||

| Rebound | Yes | 16 (44) | 75 (97) | < 0.001 |

| No | 20 (56) | 2 (3) | ||

| Rowsing finding | Yes | 7 (19) | 31 (40) | 0.034 |

| No | 29 (81) | 46 (60) | ||

| Fever | > 37.3 | 5 (14) | 28 (36) | 0.015 |

| < 37.3 | 31 (86) | 49 (64) | ||

| Laboratory results | ||||

| Neutrophil | > %75 | 10 (28) | 49 (64) | 0.001 |

| < %75 | 26 (72) | 28 (36) | ||

| Leukocyte | < 10000 | 15 (42) | 13 (17) | 0.009 |

| ≥ 10000 | 21 (58) | 64 (83) | ||

| Urine analysis | Normal | 24 (67) | 75 (97) | < 0.001 |

| Abnormal | 12 (33) | 2 (3) | ||

When the sensitivity and specificity levels of the scoring systems were assessed, they were 82% and 75% for the Alvarado, 100% and 28% for the RIPASA, 96% and 42% for the Ohmann, and 100% and 44% for the Eskelinen scores. When the negative appendectomy rates of the Alvarado, RIPASA Ohmann and Eskelinen scoring systems were assessed, they were found to be 12%, 25%, 22% and 21%, respectively (Table 3). When a cut-off value for the Alvarado system was set at 6.5, its sensitivity was calculated as 81%. When a cut-off value for the Ohmann system was set at 13.75, its sensitivity was calculated as 83.1%. When a cut-off value for the Eskelinen system was set at 63.72, its sensitivity was calculated as 80.5%. When a cut-off value for the RIPASA system was set at 10.25, its sensitivity was calculated as 83.1% (Figure 1 and Table 4).

| Alvarado (cut-off = 7) | Ohhmann (cut-off = 12) | Eskelinen (cut-off = 57) | RIPASA (cut-off = 7.5) | |

| Sensitivity | 82% | 96% | 100% | 100% |

| Specificity | 75% | 42% | 44% | 28% |

| PPV | 88% | 78% | 79% | 75% |

| NPV | 66% | 83% | 100% | 100% |

| Diagnostic accuracy | 80% | 79% | 82% | 77% |

| Neg. app. rate | 12% | 22% | 21% | 25% |

| Measurements | AUC | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| Alvarado | 0.818 | 6.50 | 81.8 | 75.0 |

| Ohmann | 0.899 | 13.75 | 83.1 | 80.6 |

| Eskelinen | 0.867 | 63.72 | 80.5 | 83.3 |

| RİPASA | 0.857 | 10.25 | 83.1 | 75.0 |

The diagnosis of acute appendicitis still represents one of the most difficult problems in surgery[7]. It is generally accepted that the removal of a normal appendix is safer in questionable cases and that delaying surgery leads to an increased rate of perforation[8]. There have been many attempts to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. In addition to clinical evaluation, with the variety of clinical signs and symptoms, many of the modern diagnostic tools have proved to be effective for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis[1,7,8]. Although sonography and CT increase the accuracy of the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, they are unfortunately still often unavailable in some emergency departments[9,10]. Several scoring systems that have been devised for the purpose of increasing both the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis of acute appendicitis have been repeatedly tested[2-5]. Scoring systems represent an inexpensive, non-invasive and easy to use diagnostic aid.

According to previous publications, the criteria for diagnostic quality have been postulated as a 15% rate of negative appendectomies, a 10% rate of negative laparotomies, a 35% rate of potential perforations, a 15% rate of overlooked perforations and a 5% rate of overlooked acute appendicitis[9,10]. Although the negative appendectomy rate reported by surgeons advocating early surgical intervention in suspected cases to prevent perforation varies between 20% and 40%, the generally accepted negative appendectomy rate is approximately 15%-20%[11-13]. Furthermore, misdiagnosis and late surgical intervention leads to complications with high morbidity and mortality, such as perforation and peritonitis. In the present study, 83.2% of the patients underwent surgery, while 16.8% were followed non-operatively. Of the patients who underwent surgery, 81.9% were histopathologically diagnosed with acute appendicitis, 6.38% were diagnosed to have pathologies other than appendicitis, and 11.71% underwent a negative appendectomy.

Acute appendicitis typically presents itself with pain that starts in the epigastrium or around the stomach and localizes to the lower right quadrant. A study by Ortega-Deballon et al[14] reported that the acute appendicitis diagnosis rate found in patients presenting with pain in the lower right quadrant was 65%. Similarly, Lane et al[15] reported this rate as 55%. In the present study, 68% of the patients who presented with pain in the lower right quadrant were histopathologically proven to have acute appendicitis.

Non-surgical pathologies can be found on physical examination and laboratory analyses in 20%-25% of the cases presenting with acute pain in the lower right quadrant, and these cases can be followed using conservative methods[16,17]. Furthermore, 5%-15% of cases with suspected acute appendicitis cannot be diagnosed despite an aggressive work-up[18]. In the present study, the rate of patients who could be followed non-operatively was 21%. The rate of patients with symptoms that receded clinically was 5%.

The idea of improving the diagnostic accuracy simply by assigning numeric values to defined signs and symptoms has been the goal of some of the scores that were previously described[1-5]. The parameters comprising the score usually include general signs of abdominal illness (e.g., type, location and migration of pain, body temperature, signs of peritoneal irritation, nausea, vomiting, etc.) and routine laboratory findings (leukocytosis)[19]. Ohmann et al[3] performed a multivariate analysis, and of the initial 15 parameters, eight were included in a regression model, resulting in different values being attributed to each parameter. Originally, it was proposed that patients with scores less than six should not be considered to have appendicitis. However, patients with scores of six or more should undergo observation, and those with scores of 12 or more should proceed to immediate appendectomy[3]. The Eskelinen score delivered acceptable clinical results after calibration to a cut-off value of 57[5]. The Alvarado score is widely used for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. The score is calculated over 10 points, and a score higher than six is indicative of acute appendicitis. On the other hand, a score of less than four indicates that it is unlikely that the patient has appendicitis. For scores of 4-6, follow-up or imaging with computerized tomography is recommended[4]. Chaudhuri et al[20], in their series of 175 patients with a mean age of 30 years, reported a negative cut-off point of five. The RIPASA score is a relatively new diagnostic scoring system and has been shown to have a significantly higher sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic accuracy[2,21]. The RIPASA score is easy to apply and includes several parameters that are absent in the Alvarado score, such as age, gender and the duration of symptoms prior to presentation[22,23]. Our study calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the Alvarado scoring system as 82% and 75%, respectively, and calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the RIPASA scoring system as 100% and 28%, respectively. Although the diagnostic accuracy levels of these two scoring systems were comparable, the RIPASA scoring system is considered less accurate because of the higher negative appendectomy rates. The negative appendectomy rate calculated in our study was 12%. When the accuracy measures of all of the scoring systems included in our study were analyzed, they performed better, especially if the cut-off values were increased. A higher cut-off value leads to 100% sensitivity and a negative predictive value for the RIPASA and Eskelinen methods and leads to 96% sensitivity with an 83% negative predictive value for the Ohmann method. When these values are assessed, it is found that the Ohmann and Eskelinen methods are one step ahead in terms of detecting appendicitis, although they fail to meet expectations in terms of specificity. The disadvantage of the Eskelinen scoring system is the practicality of calculations because values in this system are decimals, and in other systems they are integers.

For the scoring systems, sensitivity and specificity values higher than 80% are acceptable[24,25]. This is why these scoring systems may prove more advantageous when the cut-off values are customized to clinical populations. Our study showed a sensitivity level of 81% for the Alvarado system when the cut-off value was set at 6.5, a sensitivity level of 83.1% for the Ohmann system when the cut-off value was set at 13.75, a sensitivity level of 80.5% for the Eskelinen system when the cut-off value was set at 63.72, and a sensitivity level of 83.1% for the RIPASA system when the cut-off value was set at 10.25.

The main limitation of our study is the relatively small number in our series. In addition, some details regarding the history and factors that may influence the outcome may not have been completely documented. Due to these restrictions, associations should be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, the Ohmann and RIPASA scoring systems have the highest specificity for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Several scoring systems have been devised to aid decision making in doubtful acute appendicitis cases, including the Ohmann, Alvarado, Eskelinen, Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Saleha Appendicitis (RIPASA) and several others.

To assess the reliability and practical applicability of the widely used Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohhmann and RIPASA scoring systems in patients with suspected acute appendicitis.

The Ohmann and RIPASA scoring systems have the highest specificity for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Accurate identification of patients who require immediate surgery as opposed to those who will benefit from active observation is always useful.

The Alvarado, Eskelinen, Ohhmann and RIPASA are common scoring systems that are used in patients with suspected acute appendicitis.

This study is a prospective one and was conducted over 5-mo period and managed to recruit 113 patients (62 males and 51 females); 94 patients underwent surgery. This could be the first study comparing the four scoring systems in term reliability in diagnosing appendicitis.

P- Reviewers: Bai YZ, Basoli A, Meshikhes AWN S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Christian F, Christian GP. A simple scoring system to reduce the negative appendicectomy rate. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:281-285. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chong CF, Adi MI, Thien A, Suyoi A, Mackie AJ, Tin AS, Tripathi S, Jaman NH, Tan KK, Kok KY. Development of the RIPASA score: a new appendicitis scoring system for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Singapore Med J. 2010;51:220-225. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ohmann C, Yang Q, Franke C. Diagnostic scores for acute appendicitis. Abdominal Pain Study Group. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:273-281. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557-564. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Eskelinen M, Ikonen J, Lipponen P. Contributions of history-taking, physical examination, and computer assistance to diagnosis of acute small-bowel obstruction. A prospective study of 1333 patients with acute abdominal pain. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:715-721. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Horzić M, Salamon A, Kopljar M, Skupnjak M, Cupurdija K, Vanjak D. Analysis of scores in diagnosis of acute appendicitis in women. Coll Antropol. 2005;29:133-138. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sitter H, Hoffmann S, Hassan I, Zielke A. Diagnostic score in appendicitis. Validation of a diagnostic score (Eskelinen score) in patients in whom acute appendicitis is suspected. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389:213-218. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Borgstein PJ, Gordijn RV, Eijsbouts QA, Cuesta MA. Acute appendicitis--a clear-cut case in men, a guessing game in young women. A prospective study on the role of laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:923-927. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Park JS, Jeong JH, Lee JI, Lee JH, Park JK, Moon HJ. Accuracies of diagnostic methods for acute appendicitis. Am Surg. 2013;79:101-106. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Linam LE, Munden M. Sonography as the first line of evaluation in children with suspected acute appendicitis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:1153-1157. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kanumba ES, Mabula JB, Rambau P, Chalya PL. Modified Alvarado Scoring System as a diagnostic tool for acute appendicitis at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Surg. 2011;11:4. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Oyetunji TA, Ong’uti SK, Bolorunduro OB, Cornwell EE, Nwomeh BC. Pediatric negative appendectomy rate: trend, predictors, and differentials. J Surg Res. 2012;173:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wagner PL, Eachempati SR, Soe K, Pieracci FM, Shou J, Barie PS. Defining the current negative appendectomy rate: for whom is preoperative computed tomography making an impact? Surgery. 2008;144:276-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ortega-Deballon P, Ruiz de Adana-Belbel JC, Hernández-Matías A, García-Septiem J, Moreno-Azcoita M. Usefulness of laboratory data in the management of right iliac fossa pain in adults. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1093-1099. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lane R, Grabham J. A useful sign for the diagnosis of peritoneal irritation in the right iliac fossa. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1997;79:128-129. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Estey A, Poonai N, Lim R. Appendix not seen: the predictive value of secondary inflammatory sonographic signs. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:435-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gendel I, Gutermacher M, Buklan G, Lazar L, Kidron D, Paran H, Erez I. Relative value of clinical, laboratory and imaging tools in diagnosing pediatric acute appendicitis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2011;21:229-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cole MA, Maldonado N. Evidence-based management of suspected appendicitis in the emergency department. Emerg Med Pract. 2011;13:1-29; quiz 29. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Zakaria O, Sultan TA, Khalil TH, Wahba T. Role of clinical judgment and tissue harmonic imaging ultrasonography in diagnosis of paediatric acute appendicitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chaudhuri A. Re: Chan MYP, Tan C, Chiu MT, Ng YY. Alvarado score: an admission criterion in patients with right iliac fossa pain. Surg J R Coll Surg Edinb Irel 2003; 1 (1): 39-41. Surgeon. 2003;1:243-244; author reply 244. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Chong CF, Thien A, Mackie AJ, Tin AS, Tripathi S, Ahmad MA, Tan LT, Ang SH, Telisinghe PU. Comparison of RIPASA and Alvarado scores for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:340-345. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Abdeldaim Y, Mahmood S, Mc Avinchey D. The Alvarado score as a tool for diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ir Med J. 2007;100:342. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Saidi HS, Chavda SK. Use of a modified Alvorado score in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. East Afr Med J. 2003;80:411-414. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Kırkıl C, Karabulut K, Aygen E, Ilhan YS, Yur M, Binnetoğlu K, Bülbüller N. Appendicitis scores may be useful in reducing the costs of treatment for right lower quadrant pain. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:13-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Konan A, Hayran M, Kılıç YA, Karakoç D, Kaynaroğlu V. Scoring systems in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the elderly. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17:396-400. [PubMed] |