INTRODUCTION

Desmoid tumors (DTs), also known as musculo-aponeurotic fibromatoses, are locally aggressive soft tissue neoplasms histologically characterized by fibroblastic proliferation within a collagen matrix[1]. Intra-abdominal DTs are associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Gardner syndrome, and they may also occur sporadically or subsequent to localized trauma (surgical or nonsurgical). DTs possess negligible metastatic potential and frequently remain asymptomatic for extended periods of time before a diagnosis can be made on the basis of either vague, chronic symptoms or obvious mechanical complications. Aggressive expansion into adjacent tissues results in significant morbidity due to nerve and organ damage, and the mortality rate due to DTs approaches 10%. DTs also present a considerable dilemma for clinicians because of their high rates of recurrence after surgery, especially following conservative resection. The pancreas is a rather rare location for DTs, even though sporadic DTs are found within the pancreas more frequently than sporadic intra-abdominal DTs[2]. Since 1956 when Wilson reported the first case of a pancreatic DT resembling a pancreatic pseudocyst, only a few similar cases have been reported[1,3].

Here, we report a 17-year-old patient presenting with a sporadic cystic DT of the pancreas, and subsequent disease management with central pancreatectomy. Pertinent English-language literature is also reviewed and summarized.

CASE REPORT

In June 2009, a 17-year-old boy presented to the gastroenterology department in our hospital with complaints of upper abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting for 5 d. He had not had passage of stools for 2 d. He denied hematemesis, melena, diarrhea, weight loss or fever. Past medical and surgical history was unremarkable and he denied any abdominal trauma. Abdominal auscultation revealed no abnormalities and percussion elicited splashing sounds in the upper abdominal region. A mass of 6 cm × 5 cm was palpated in the left upper quadrant without tenderness or rebound tenderness. Neither abdominal muscle guarding nor enlarged superficial lymph nodes were noted. Admission laboratory data were within normal limits, and serum tumor marker levels [carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen (CA) 19-9] were not elevated. Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a solid cystic mass within the body of the pancreas (Figure 1). Abdominal plain X-rays revealed no apparent signs of bowel obstruction, while gastroscopy demonstrated intragastric fluid retention with luminal compression from a mass within the outer gastric wall (Figure 2). Abdominal computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast delineated a cystic mass within the central pancreas, invading the horizontal part of the underlying duodenum (Figure 3). Additionally, endoluminal ultrasonography (EUS) demonstrated a cystic hypoechoic tumor posterior to the stomach of 6.7 cm × 5.5 cm and containing four cystic cavities (Figure 4). Examination of EUS-guided fine needle aspirate only demonstrated inflammatory tissue; however, cystic fluid examination revealed elevated levels of both CEA and CA19-9, at 1378 and 425.4 ng/mL, respectively. In light of the aforementioned pancreatic mass and resultant duodenal obstruction, the patient was transferred to the Department of General Surgery for emergency exploratory laparotomy.

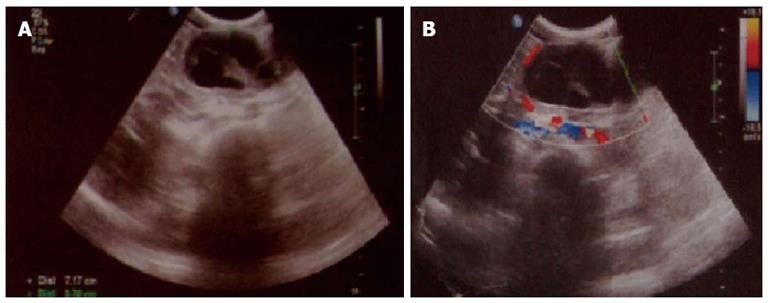

Figure 1 Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a solid cystic mass within the body of the pancreas.

A: Ultrasonography showed a solid cystic mass within the body of the pancreas; B: Ultrasonography showed that the mass was surrounded by blood vessels.

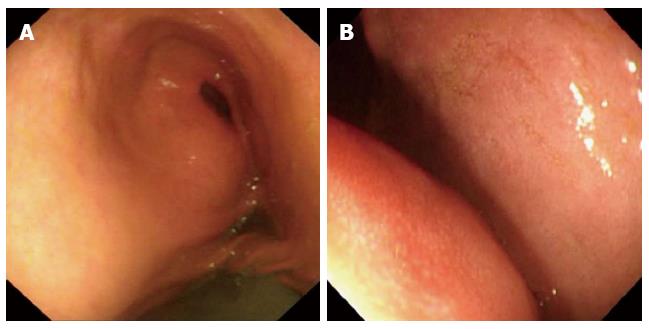

Figure 2 Gastroscopic imaging demonstrating fluid within the stomach and wall compression caused by an external mass.

A: Gastroscopy demonstrated intragastric fluid retention; B: Stomach wall compression by an external mass.

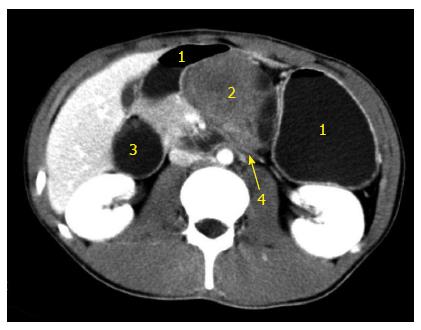

Figure 3 Abdominal computed tomography with contrast (venous phase) demonstrating a solid cystic mass invading the horizontal portion of the duodenum.

1: Stomach; 2: Pancreatic cystic mass; 3: Enlarged duodenum; 4: Horizontal duodenal portion invaded by the tumor.

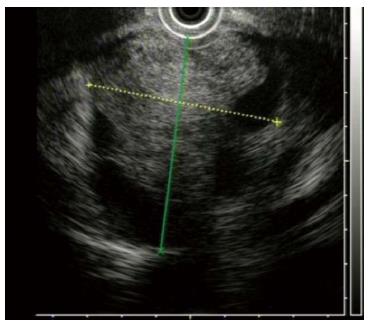

Figure 4 Endoscopic ultrasonography revealing a pancreatic cystic hypoechoic tumor located posterior to the stomach, with four cystic cavities, about 6.

7 cm × 5.5 cm in dimension.

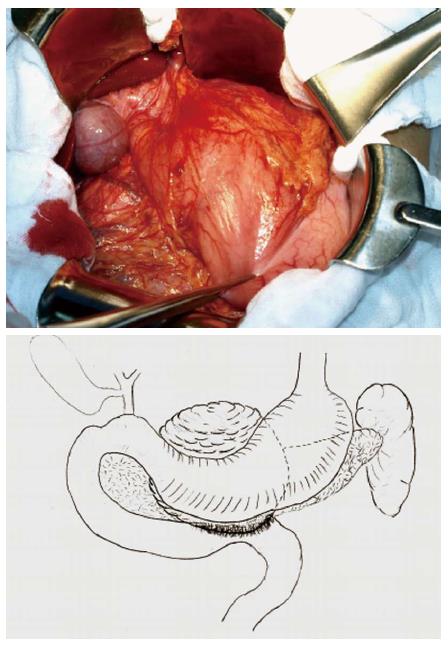

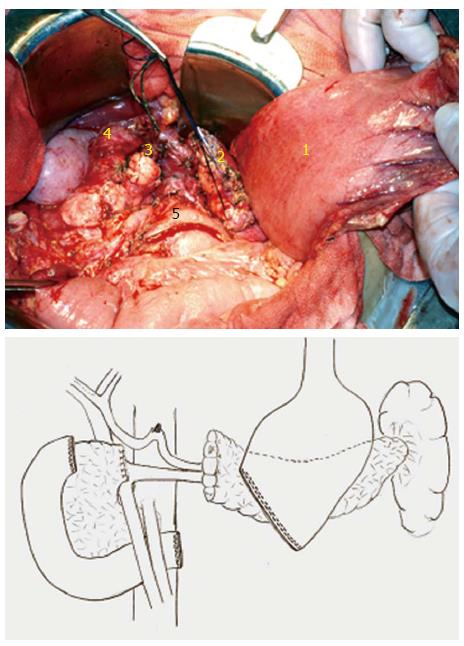

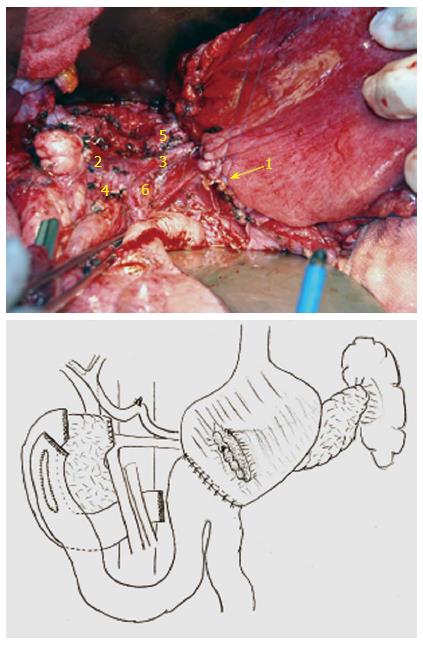

During the surgery, a solid cystic mass of 8.6 cm × 6.0 cm within the pancreatic neck and body invading the adjacent horizontal portion of the duodenum was noted (Figure 5). The mass was adjacent to the posterior wall of the stomach. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. The tumor was primarily located within the central pancreas, therefore, central pancreatectomy was deemed in order, accompanied by partial distal stomach and horizontal duodenal en bloc resection (Figure 6). Digestive tract reconstruction was performed via pancreaticogastrostomy, duodenojejunostomy (side to side) and gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II, Figure 7). The postoperative course was uneventful; total parenteral nutrition was provided for 7 d after surgery and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 12. Follow-up examinations with CT, gastroscopy, gastrointestinal imaging and colonoscopy were performed once every 6 mo. The patient recovered well with no complaints of discomfort, malnutrition, or bowel movement abnormalities and continued his study in school as previously. CT showed no recurrence 20 mo postoperatively (Figure 8).

Figure 5 Exploratory laparotomy revealed a cystic mass of size 8.

6 cm × 6.0 cm within the pancreatic neck and body invading the horizontal duodenum.

Figure 6 The central pancreas (containing the tumor), distal stomach and duodenal portion were all resected.

1: Stomach; 2: Left resected end of pancreas; 3: Right resected end of pancreas; 4: Upper resected end of duodenum; 5: Lower resected end of duodenum.

Figure 7 Reconstruction was performed via pancreaticogastrostomy, duodenojejunostomy (side to side) and gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II).

1: Pancreaticogastrostomy; 2: Portal vein; 3 Splenic vein; 4: Superior mesenteric vein; 5: Splenic artery; 6: Superior mesenteric artery.

Figure 8 Contrast computed tomography examination (arterial phase) demonstrated no recurrence 18 mo after operation.

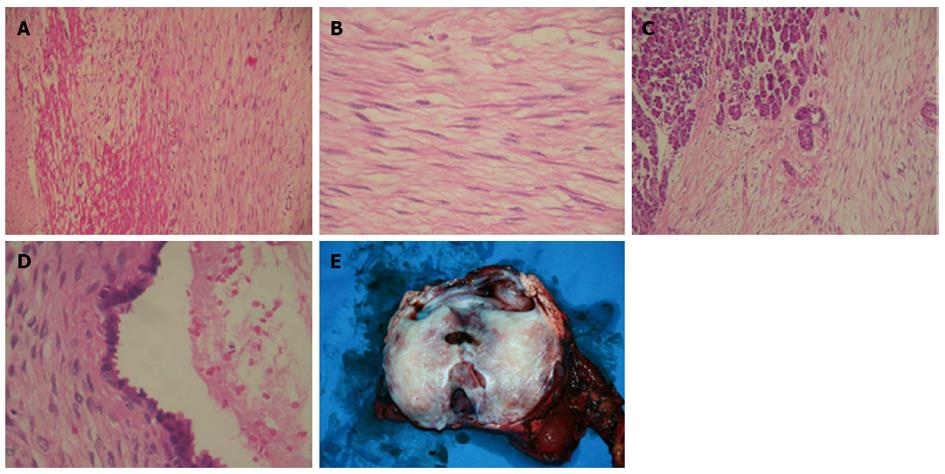

Pathological examination identified a pancreatic DT with several cystic cavities and adjacent duodenal invasion. Histological sections of the solid tumor showed proliferation of spindle-shaped or stellate cells, growing in fasciculate and storiform patterns within a myxoid intercellular matrix. The cystic lesion was lined predominantly by chronically inflamed fibrous tissue and small areas of benign columnar epithelium. Specimen surfaces from the stomach and duodenum contained a mesenteric plaque composed of well-defined sheets of densely collagenized fibrous tissue, which entrapped fat, blood vessels, nerve fibers, and smooth muscle. In the areas between the solid tumor and pancreatic parenchyma, the mesenteric plaque merged with the desmoid masses, entrapping pancreatic acini and resulting in irregularly dilated ducts. The cystic area was the result of dilatation of entrapped excretory pancreatic ducts (Figure 9). Subsequent immunohistochemical analysis found smooth muscle actin and cytokeratin to be positive, while desmin, CD117 (c-kit), CD34, S-100, calretinin and estrogen receptor (ER) were negative.

Figure 9 Pathological examination.

A: Pancreatic desmoid tumor with invasion to the duodenal wall; B: Proliferation of spindle-shaped stellate cells in fasciculate and storiform growth patterns within a myxoid intercellular matrix; C: Pancreatic infiltration by the tumor; D: The cystic area resulted from dilatation of entrapped excretory pancreatic ducts; E: Gross view of resected tumor and pancreas.

DISCUSSION

DTs are rare and first appeared in the medical literature in the early 19th century. The term is derived from the Greek “desmos”, describing a band- or tendon-like attribute. DTs represent approximately 0.03% of all tumors and 3% of soft tissues tumors[4]. They are nonmetastatic and locally aggressive, with a high local recurrence rate, and may arise virtually anywhere within the body. The tumors are benign and are characterized by the absence of pleomorphism, atypia, or hyperchromatic nuclei[5]. Desmoids are particularly predisposed to muscular fascia, but may occur at any fascia. The most frequent sites for these tumors are the torso and extremities. Recent clinical studies have demonstrated that 37%-50% of DTs arise in the abdominal region[4,6,7].

DTs have recently been classified depending on their point of origin as extra-abdominal, abdominal and intra-abdominal; the latter type further subclassified into mesenteric and pelvic fibromatoses[8]. Associations between abdominal desmoids with FAP and Gardner syndrome have been well documented, suggesting a genetic predisposition to such lesions. Abdominal desmoids occur more frequently in FAP patients, with an incidence of 3.5%-32%, while in the original Gardner syndrome, the incidence was 29%[4,9]. In both FAP and familial non-FAP tumors, mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene on the long arm of chromosome 5 has been implicated as the primary causative mechanism. As a result of APC mutation, β-catenin degradation markedly decreases, promoting fibroblastic proliferation via nuclear signaling pathways[10].

DT etiology has not been well defined. A history of trauma to the site of the tumor, often surgical in nature, may be elicited in approximately 25% of cases[11,12]. Anecdotal evidence of tumor regression during menopause[13], the development of desmoids in patients taking oral contraceptives[14], and reports of tumor regression with tamoxifen treatment[15] underline the apparent role of estrogen in the multifactorial pathogenesis of the neoplasm.

The pancreas is an extremely rare location for DT manifestation. Moreover, pancreatic desmoids resembling solid cystic tumors are the rarest form of DTs. Most relevant literature concerns FAP-associated desmoids; only nine cases of pancreatic DTs have been described in the English literature to date[2,16-22]. Although intra-abdominal DTs are widely considered to be associated with FAP, such association was noted in only one of the 10 reported cases (including our present case) of pancreatic DTs. Pancreatic DTs occurring after pancreatic surgery or biopsy were noted in three of the 10 reported cases[18,19]. Presenting symptoms consisted mainly of epigastric pain (6/10) and weight loss (4/10). The pancreatic DTs were mostly localized to the tail (6/10) and measured 15-85 mm in length.

In the present case, the patient was initially diagnosed with a mucinous cystic or solid pseudopapillary neoplasm. These diagnoses were suggested due to the cystic characteristics of the tumor, and pathological examination revealed the cystic components bearing a resemblance to retention cysts. Only two previously published cases of pancreatic DTs presented as cystic tumors[21]. In the first case, the cystic component corresponded to a benign retention cyst. The other case corresponded to an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm situated adjacent to a DT, but lacking true intralesional cystic components[19].

Differentiating DTs from other types of soft tissue neoplasms may be difficult based on histological analyses alone. Expression was negative for CD34, CD117, S-100 and desmin, which excluded a gastrointestinal stromal tumor, solitary fibrous tumor, schwannoma, leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, respectively[23,24]. DTs are theoretically associated with clonal myofibroblastic proliferation and somatic mutation of the Wnt/β-catenin gene, leading to the intranuclear accumulation of β-catenin. Recent efforts in immunostaining of intranuclear β-catenin and the gene responsible for its mutation proved efficient in discriminating DTs from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions[25].

In the case of intra-abdominal DTs, surgical resection is generally performed in the event of extensive tumor invasion and potentially life-threatening complications. However, resection is usually a difficult procedure because of considerable vascular involvement among the mesenteric and retroperitoneal areas. In this case, the tumor was located in the pancreatic neck and body, invading the horizontal portion of the duodenum and the posterior stomach wall. In order to perform resection with a tumor-free margin, central pancreatectomy with accompanying en bloc resection of the distal stomach and horizontal duodenal portion was deemed appropriate (Figure 6). Digestive tract reconstruction mandated three anatomoses for continuity maintenance (Figure 7).

Intra-abdominal DTs possess high rates of local recurrence after surgical resection, particularly in patients with FAP or Gardner syndrome. Intriguingly, frequent recurrences appear to be absent in cases of sporadic pancreatic DTs, according to the limited number of follow-up reports available[2,16-22]. A single reported case of recurrence was noted in a patient with FAP by Pho et al[21]. The present case remains disease free 40 mo after surgery, consistent with previous reports.

In summary, the pancreas remains a rare location for DTs. Pancreatic DTs presenting as solid cystic tumors are the rarest form of desmoids. There are no notable clinical symptoms, tumor markers or imaging features to aid in diagnosis. Nuclear immunostaining of the β-catenin protein and its corresponding coding gene are efficient in distinguishing DTs from other lesions. Cytotoxic treatments may be utilized for either unresectable neoplasms or those unresponsive to more benign treatment, as radiotherapy may be limited in use due to extensive bowel geography. Radical surgical resection with tumor-free margins appears to produce an excellent prognosis when applicable.