Published online Dec 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8740

Revised: September 20, 2013

Accepted: October 13, 2013

Published online: December 14, 2013

Processing time: 143 Days and 14 Hours

AIM: To evaluate long-term survival after the Whipple operation with superior mesenteric vein/portal vein resection (SMV/PVR) in relation to resection length.

METHODS: We evaluated 118 patients who underwent the Whipple operation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma at our Department of Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery between 2005 and 2010. Fifty-eight of these patients were diagnosed with microscopic PV/SMV invasion by frozen-section examination and underwent SMV/PVR. In 28 patients, the length of SMV/PVR was ≤ 3 cm. In the other 30 patients, the length of SMV/PVR was > 3 cm. Clinical and survival data were analyzed.

RESULTS: SMV/PVR was performed successfully in 58 patients. There was a significant difference between the two groups (SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm and SMV/PVR > 3 cm) in terms of the mean survival time (18 mo vs 11 mo) and the overall 1- and 3-year survival rates (67.9% and 14.3% vs 41.3% and 5.7%, P < 0.02). However, there was no significant difference in age (64 years vs 58 years, P = 0.06), operative time (435 min vs 477 min, P = 0.063), blood loss (300 mL vs 383 mL, P = 0.071) and transfusion volume (85.7 mL vs 166.7 mL, P = 0.084) between the two groups.

CONCLUSION: Patients who underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm had better long-term survival than those with > 3 cm resection.

Core tip: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma can infiltrate the portal vein (PV) or superior mesenteric vein (SMV). In order to achieve negative surgical margins, the Whipple operation combined with SMV/PV resection (SMV/PVR) is usually performed. The long-term survival rate of patients with SMV/PV involvement in relation to the length of resection remains controversial.

- Citation: Pan G, Xie KL, Wu H. Vascular resection in pancreatic adenocarcinoma with portal or superior mesenteric vein invasion. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(46): 8740-8744

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i46/8740.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8740

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a malignant neoplasm that is one of the most common causes of cancer-related death. Unfortunately, there are no symptoms in the early period of the disease, so fewer patients have the chance of achieving negative margin resection. The reason for the lower treatment rate is that many patients have liver metastases, lymph node involvement, invasion of retroperitoneal tissue, and portal vein (PV)/superior mesenteric vein (SMV) invasion when they are diagnosed[1-4]. Since the Whipple operation combined with SMV/PV resection (SMV/PVR) and reconstruction for pancreatic adenocarcinoma was first reported in 1951[5], the value of SMV/PVR has remained controversial[6,7]. In the past, tumor invasion of the PV/SMV was considered a contraindication to tumor resection because of the high rate of recurrence and poor prognosis. Recently, some departments have argued that combination of the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR can achieve similar long-term survival to the Whipple operation alone without any increase in morbidity and mortality[8-10].

However, the suitable length of SMV/PVR is under discussion. In this study, we evaluated the outcome in patients who underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm compared with > 3 cm. We aimed to clarify long-term survival of patients with SMV/PV invasion in relation to the depth of venous involvement.

From January 2005 to December 2010, 118 consecutive patients who underwent the Whipple operation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma were analyzed at the Department of Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Surgery, Sichuan University. There were 70 men and 48 women with a median age of 53 years (range, 23-78 years). According to preoperative image evaluation and intraoperative frozen-section examination, 60 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma underwent the Whipple operation alone. Twenty-eight patients underwent the Whipple operation combined with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm. Thirty patients underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR > 3 cm.

Preoperative evaluation included a careful physical examination; a series of blood tests such as tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9), liver function, and thrombin; and chest radiography, abdominal ultrasonography, contrast computed tomography, and electrocardiography. Sometimes magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was selectively performed.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) extrapancreatic disease such as liver and peritoneal metastases; (2) Whipple operation with SMV/PVR tangential resection; and (3) Whipple operation combined with adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. We also excluded patients with a previous unsuccessful attempt at pancreatectomy because they could be exposed to different early morbidity or distant prognosis.

The Whipple operation was performed in all of the consecutive patients. Hemigastrectomy was performed, and the bile duct was divided above the cystic duct. An end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy, end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy, and side-to-side gastrojejunostomy were performed as classic reconstruction after the Whipple operation[10]. Vascular consecutiveness was recovered by a direct end-to-end anastomosis. None of the patients in our group used low-molecular-weight heparin after venous reconstruction.

Perioperative data such as pathological data, length of hospital stay, operative blood loss, volume of blood transfusion, morbidity, and mortality were obtained from medical records. The long-term survival outcomes were obtained through postoperative follow-up at outpatient clinics or on the telephone. The outcomes in the two groups were analyzed using the χ2 test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0, when P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The demographic and operative characteristics of the patients who underwent SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm and > 3 cm are shown in Table 1. The median age of the two groups was 64 years (range, 31-78 years) and 58 years (range, 38-77 years), respectively. The median size of the pancreatic tumors was 3.1 cm (range, 2-6 cm) and 3.7 cm (range, 3-7 cm), respectively. The median length of venous resection was 2.5 cm (range, 1-3 cm) and 3.8 cm (range, 3.5-5 cm), respectively. The mean operation time for patients with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm and > 3 cm was 435 and 477 min, respectively. The mean blood loss was 300 and 383 mL, respectively. There was no significant difference in operative time, blood loss, transfusion volume, and tumor stage between the two groups. However, there were significant differences in lymph node invasion, depth of venous involvement, and length of SMV/PVR between the two groups. By multivariate analysis, the length of venous resection was the most important prognostic factor.

| Demographics | SMV/PVR ≤3 cm | SMV/PVR > 3 | P value |

| (n = 28) | cm (n = 30) | ||

| Sex (M/F) | 21/7 | 20/10 | 0.082 |

| Age (yr) | 64 (range 31-78) | 58 (range 38-77) | 0.063 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.1 (range 2-6) | 3.7 (range 3-7) | 0.051 |

| Tumor stage | 0.056 | ||

| I | 5 | 2 | |

| II | 16 | 6 | |

| III | 7 | 22 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Curability | 0.067 | ||

| R0 | 26 | 22 | |

| R1+ | 2 | 8 | |

| Depth of venous involvement | 0.032 | ||

| Tunica adventitia | 4 | 2 | |

| Tunica media | 14 | 12 | |

| Tunica intima | 10 | 16 | |

| Lymph node invasion | 25% | 73% | 0.043 |

| Operative time (min) | 435 | 477 | 0.064 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 300 | 383 | 0.071 |

| Transfusion (mL) | 85.7 | 166.7 | 0.084 |

The postoperative complication and mortality rates are shown in Table 2. Hemorrhage from the surgical site occurred in three patients after the operation, and one of these died 7 d after surgery. Two patients underwent reoperation. In the patients with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm, hypertension with upper gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in one patient who underwent spleen vein transection without vascular remodeling.

| Morbidity | SMV/PVR ≤3 cm | SMV/ PVR > 3 cm |

| (n = 28) | (n = 30) | |

| Hemorrhage | 1 | 2 |

| Hypertension with upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 0 | 1 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 2 | 3 |

| Wound infection | 1 | 1 |

| Reoperation | 1 | 1 |

| Recurrence | 21 | 27 |

| Median hospital stay (d) | 18 (range 8-32) | 18 (range 11-43) |

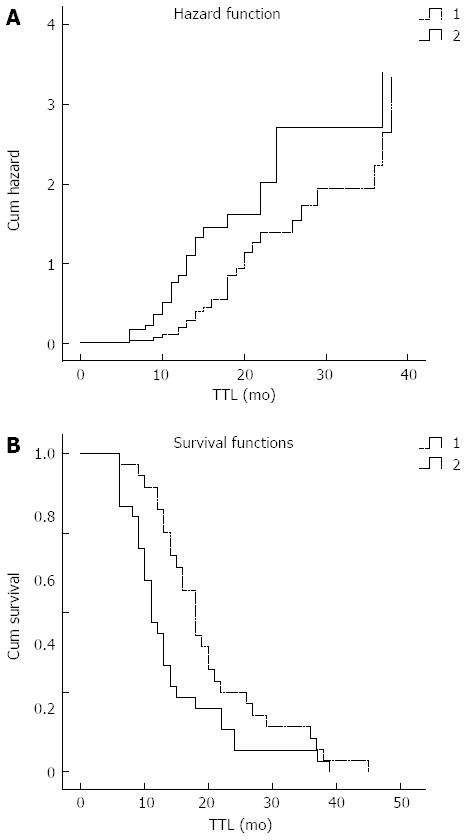

The overall 1- and 3-year survival rates for patients who underwent the standard Whipple operation combined with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm (n = 28) and SMV/PVR > 3 cm (n = 30) were 67.9% and 14.3%, and 41.3% and 5.7%, respectively. The mean survival of patients with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm and SMV/PVR > 3 cm was 18 and 11 mo, respectively. There was a significant difference in survival between the two groups (Figure 1; P = 0.02).

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a malignant disease and negative resection margin is still the best treatment option at present. In the past, only 10%-20% of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma could undergo surgery because of distant metastases and vascular involvement[11-13]. Due to the intimate relationship of the pancreatic head and uncinate, the PV is always infiltrated[9]. Surgeons previously considered that pancreatic adenocarcinoma with venous involvement was a contraindication to surgery. They also considered that venous invasion always hindered complete tumor removal. Recent improvements in preoperative imaging and surgical techniques have resulted in the standard Whipple operation with SMV/PVR offering the possibility of achieving negative margin resection in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and SMV or PV involvement, without a relevant increase in morbidity and mortality[14-16]. Our study also supports this. However, the suitable length of SMV/PVR is under discussion.

The main conclusion of our retrospective analysis was that patients who underwent the standard Whipple operation with SMV/PVR (Group 1) had similar survival rates and negative resection margins when compared with patients without PV involvement (Group 2). In our study, the median survival time in Group 1 (n = 58) and Group 2 (n = 60) was 19 and 21 mo, respectively. In addition, the 1- and 3-year survival rates in the two groups were 63.3% and 14.3%, and 69.3% and 18.4%, respectively. There were no significant differences in survival between the two groups (P > 0.05). At the same time, the blood loss, volume of transfusion, and surgical mortality and morbidity did not increase obviously in Group 1. However, venous resection combined with reconstruction (Group 1) cost more compared with Group 2, but there was no significant difference in survival between the two groups (P > 0.05). Therefore, we considered that patients with SMV/PVR had similar long-term survival to those without SMV/PVR.

Another conclusion is that patients who underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm (Group 3) achieved better long-term survival than those with SMV/PVR > 3 cm (Group 4). Median survival time in Group 3 (n = 28) and Group 4 (n = 30) was 18 and 11 mo, respectively. There was a significant difference in survival between the two groups (P < 0.02). Meanwhile, the patients with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm had more risk factors compared with those with SMV/PVR > 3 cm (P < 0.05) (Figure 1). For example, the ratio of lymph node invasion between the two groups was 25% and 73%, respectively, and this difference was significant (P < 0.05). Therefore, we consider that 3 cm is a suitable length of SMV/PVR.

Illuminati et al[17] reported that standard Whipple operation combined with PV or SMV resection can be performed when venous involvement does not exceed 2 cm. They have suggested that more complex vein reconstruction could lead to a greater rate of postoperative complications. They have also clarified that 2 cm is the maximal extent that allows one to achieve margin-free resection with simple vascular reconstruction and tension-free anastomosis. However, in our study, we achieved tension-free end-to-end anastomosis by dissociating the root of the SMV when the length of PVR was about 5 cm. Recently, some institutions have suggested that a distance of up to 8 cm can achieve primary anastomosis by this procedure[6,18]. Thus, we believe that the main factor influencing the length of venous resection is not the surgical technique itself but the long-term survival. Our study indicated that patients who underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm achieved better long-term survival.

Some studies have reported the use of venous interposition graft[10,19-21]. They have proposed that SMV/PVR > 5 cm and venous collateral formations should use venous interposition grafting[14]. The autogenous venous graft often uses the internal jugular and the greater saphenous veins. The prosthetic venous reconstruction material is usually polytetrafluoroethylene. However, Riediger et al[6] considered that the Whipple operation has a risk of abdominal infection, and the use of venous prostheses might increase this complication. In our series, all the patients with PVR had a primary end-to-end reconstruction without any autogenous graft or venous prosthesis.

Shibata et al[10] divided SMV/PVR into four types: (1) above and below the level of the splenic vein; (2) above the level of the splenic vein; (3) below the level of the splenic vein; and (4) tangential resection. In our present series, among the 58 patients who underwent the Whipple operation and venous resection, 10 underwent PVR above and below the level of the splenic vein. Among these 10 patients, 4 patients underwent vena lienalis ligatured and transected without splenic vein reconstruction, and six patients had vena lienalis ligation and resection with splenic artery wedge resection in order to reduce the blood flow to the spleen. In the four patients without splenic vein reconstruction, one had local hypertension and upper gastrointestinal bleeding and died in the 14 d after the operation. It has also been reported that division of the splenic vein without splenectomy might lead to portal thrombosis[22-24], but this did not occur in our study. Our experience suggests that splenic vein ligatured and transected with splenic artery reconstruction should be performed when the confluence of spleen vein is involved.

Shibata et al[10] have proposed that the degree of venous involvement can be divided into three types: no mural invasion, intramural invasion without tunica intima involvement, and transmural invasion. Several documents have reported that patients with tunica intima infiltration could not obtain good long-term survival[10,14]. In our study, no patient survived beyond 8 mo, when the tunica intima was involved.

Bao et al[23] have suggested that mesenteric artery involvement > 90°, as visualized by computed tomography, implies that we cannot achieve disease-free resection. Today, most surgeons agree that tumor invasion of the mesenteric artery is a contraindication to the Whipple operation[17,25,26]. It is considered that the mesenteric artery is often encircled by a neural plexus and lymph nodes. Therefore, artery involvement is always combined with neural plexus and lymph node invasion, and it is difficult to achieve a negative resection margin. It has also been reported that patients with positive lymph nodes have worse overall survival than patients without lymph node invasion, and extensive lymphadenectomy and nerve plexus resection might lead to serious diarrhea and poorer quality of life. Therefore, other treatments such as neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy could be used in patients with arterial invasion.

In conclusion, we showed that patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and venous invasion who underwent the standard Whipple operation with SMV/PVR had similar long-term survival than patients without venous involvement. In addition, patients who underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm achieved better long-term survival than those with > 3 cm resection.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a malignant neoplasm. Due to the close relationship between the pancreas and the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and portal vein (PV), pancreatic cancer can infiltrate the PV/SMV.

The Whipple operation and SMV/PV resection (SMV/PVR) has been considered the standard operation for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and PV or SMV involvement. However, the long-term survival rate of patients with PV/SMV involvement in relation to the length of SMV/PVR is under discussion.

The authors studied 118 patients who underwent the Whipple operation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma between 2005 and 2010. Fifty-eight patients were diagnosed with microscopic SMV/PV invasion by frozen-section examination and underwent SMV/PVR. Twenty-eight of these 58 patients underwent SMV/PVR < 3 cm. Thirty patients underwent SMV/PVR > 3 cm. The authors performed this retrospective study to clarify the long-term survival rate of patients with SMV/PV involvement in relation to the length of SMV/PVR by analyzing the clinical and survival data of those 58 patients.

Patients who underwent the Whipple operation with SMV/PVR ≤ 3 cm achieved better long-term survival than those with SMV/PVR > 3 cm.

The overall contents are interesting with clinical significance. The data from Whipple procedure only group should be included in tables to compare with SM-PVR groups, in particular for the parameters of time to progress or recurrence and overall survival time. In particular, the comparison of overall survival time between Whipple only and Whipple plus SM-PVR groups.

P- Reviewers: Li W, Shelat VG S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Müller SA, Hartel M, Mehrabi A, Welsch T, Martin DJ, Hinz U, Schmied BM, Büchler MW. Vascular resection in pancreatic cancer surgery: survival determinants. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:784-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Weitz J, Kienle P, Schmidt J, Friess H, Büchler MW. Portal vein resection for advanced pancreatic head cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:712-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hartel M, Niedergethmann M, Farag-Soliman M, Sturm JW, Richter A, Trede M, Post S. Benefit of venous resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:707-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Al-Haddad M, Martin JK, Nguyen J, Pungpapong S, Raimondo M, Woodward T, Kim G, Noh K, Wallace MB. Vascular resection and reconstruction for pancreatic malignancy: a single center survival study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1168-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moore GE, Sako Y, Thomas LB. Radical pancreatoduodenectomy with resection and reanastomosis of the superior mesenteric vein. Surgery. 1951;30:550-553. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Riediger H, Makowiec F, Fischer E, Adam U, Hopt UT. Postoperative morbidity and long-term survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy with superior mesenterico-portal vein resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1106-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fujisaki S, Tomita R, Fukuzawa M. Utility of mobilization of the right colon and the root of the mesentery for avoiding vein grafting during reconstruction of the portal vein. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:576-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhou Y, Zhang Z, Liu Y, Li B, Xu D. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric vein-portal Evein resection for pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2012;36:884-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bachellier P, Rosso E, Pessaux P, Oussoultzoglou E, Nobili C, Panaro F, Jaeck D. Risk factors for liver failure and mortality after hepatectomy associated with portal vein resection. Ann Surg. 2011;253:173-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shibata C, Kobari M, Tsuchiya T, Arai K, Anzai R, Takahashi M, Uzuki M, Sawai T, Yamazaki T. Pancreatectomy combined with superior mesenteric-portal vein resection for adenocarcinoma in pancreas. World J Surg. 2001;25:1002-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Carrère N, Sauvanet A, Goere D, Kianmanesh R, Vullierme MP, Couvelard A, Ruszniewski P, Belghiti J. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal vein resection for adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. World J Surg. 2006;30:1526-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bramhall SR, Allum WH, Jones AG, Allwood A, Cummins C, Neoptolemos JP. Treatment and survival in 13,560 patients with pancreatic cancer, and incidence of the disease, in the West Midlands: an epidemiological study. Br J Surg. 1995;82:111-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sener SF, Fremgen A, Menck HR, Winchester DP. Pancreatic cancer: a report of treatment and survival trends for 100,313 patients diagnosed from 1985-1995, using the National Cancer Database. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 617] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kaneoka Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M. Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma: prognostic value of the length of venous resection. Surg. 2009;145:417-425. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Harrison LE, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF. Isolated portal vein involvement in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A contraindication for resection? Ann Surg. 1996;224:342-347; discussion 347-349. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Chua TC, Saxena A. Extended pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for pancreatic cancer: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1442-1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Illuminati G, Carboni F, Lorusso R, D’Urso A, Ceccanei G, Papaspyropoulos V, Pacile MA, Santoro E. Results of a pancreatectomy with a limited venous resection for pancreatic cancer. Surg Today. 2008;38:517-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Launois B, Stasik C, Bardaxoglou E, Meunier B, Campion JP, Greco L, Sutherland F. Who benefits from portal vein resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer? World J Surg. 1999;23:926-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fuhrman GM, Leach SD, Staley CA, Cusack JC, Charnsangavej C, Cleary KR, El-Naggar AK, Fenoglio CJ, Lee JE, Evans DB. Rationale for en bloc vein resection in the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma adherent to the superior mesenteric-portal vein confluence. Pancreatic Tumor Study Group. Ann Surg. 1996;223:154-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Launois B, Franci J, Bardaxoglou E, Ramee MP, Paul JL, Malledant Y, Campion JP. Total pancreatectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas with special reference to resection of the portal vein and multicentric cancer. World J Surg. 1993;17:122-126; discussion 126-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ramacciato G, Mercantini P, Petrucciani N, Giaccaglia V, Nigri G, Ravaioli M, Cescon M, Cucchetti A, Del Gaudio M. Does portal-superior mesenteric vein invasion still indicate irresectability for pancreatic carcinoma? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:817-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Potts JR, Broughan TA, Hermann RE. Palliative operations for pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1990;159:72-77; discussion 77-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bao PQ, Johnson JC, Lindsey EH, Schwartz DA, Arildsen RC, Grzeszczak E, Parikh AA, Merchant NB. Endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography predictors of pancreatic cancer resectability. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:10-16; discussion 16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hommeyer SC, Freeny PC, Crabo LG. Carcinoma of the head of the pancreas: evaluation of the pancreaticoduodenal veins with dynamic CT--potential for improved accuracy in staging. Radiology. 1995;196:233-238. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Howard TJ, Villanustre N, Moore SA, DeWitt J, LeBlanc J, Maglinte D, McHenry L. Efficacy of venous reconstruction in patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:1089-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Konishi I, Ueno K, Ohta T, Miyazaki I. Clinicopathological study of pancreatic carcinoma with particular reference to the invasion of the extrapancreatic neural plexus. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;10:105-111. [PubMed] |