Published online Dec 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8709

Revised: September 30, 2013

Accepted: October 19, 2013

Published online: December 14, 2013

Processing time: 170 Days and 8.3 Hours

AIM: To determine the pattern and distribution of colonic diverticulosis in Thai adults.

METHODS: A review of the computerized radiology database for double contrast barium enema (DCBE) in Thai adults was performed at the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. Incomplete studies and DCBE examinations performed in non-Thai individuals were excluded. The pattern and distribution of colonic diverticulosis detected during DCBE studies from June 2009 to October 2011 were determined. The occurrence of solitary cecal diverticulum, rectal diverticulum and giant diverticulum were reported. Factors influencing the presence of colonic diverticulosis were evaluated.

RESULTS: A total of 2877 suitable DCBE examinations were retrospectively reviewed. The mean age of patients was 59.8 ± 14.7 years. Of these patients, 1778 (61.8%) were female and 700 (24.3%) were asymptomatic. Colonic diverticulosis was identified in 820 patients (28.5%). Right-sided diverticulosis (641 cases; 22.3%) was more frequently reported than left-sided diverticulosis (383 cases; 13.3%). Pancolonic diverticulosis was found in 98 cases (3.4%). The occurrence of solitary cecal diverticulum, rectal diverticulum and giant diverticulum were 1.5% (42 cases), 0.4% (12 cases), and 0.03% (1 case), respectively. There was no significant difference in the overall occurrence of colonic diverticulosis between male and female patients (28.3% vs 28.6%, P = 0.85). DCBE examinations performed in patients with some gastrointestinal symptoms revealed the frequent occurrence of colonic diverticulosis compared with those performed in asymptomatic individuals (29.5% vs 25.3%, P = 0.03). Change in bowel habit was strongly associated with the presence of diverticulosis (a relative risk of 1.39; P = 0.005). The presence of diverticulosis was not correlated with age in symptomatic patients or asymptomatic individuals (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Colonic diverticulosis was identified in 28.5% of DCBE examinations in Thai adults. There was no association between the presence of diverticulosis and gender or age.

Core tip: Based on this study in the largest university hospital in Thailand, colonic diverticulosis was identified in 28.5% of double contrast barium enemas performed in Thai adults. The incidence of colonic diverticulosis in the present study was markedly higher than that previously reported from hospital-based data of colonic diverticulosis in Thailand in 1980. This study also demonstrated that there was no significant association between the presence of diverticulosis and gender or age. However, colonic diverticulosis was more commonly reported in patients with some gastrointestinal symptoms, especially those with a change in bowel habit.

- Citation: Lohsiriwat V, Suthikeeree W. Pattern and distribution of colonic diverticulosis: Analysis of 2877 barium enemas in Thailand. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(46): 8709-8713

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i46/8709.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8709

Colonic diverticulosis is a common gastrointestinal condition in which the large intestine contains outpouchings of the mucosa and submucosa through a weak area of the colon[1]. However, the actual prevalence of colonic diverticulosis is difficult to determine because most people with colonic diverticula are asymptomatic[2]. Double contrast barium enema (DCBE) is regarded as the investigation of choice for demonstrating the presence and extent of colonic diverticulosis[3,4]. It is evident that the prevalence and pattern of colonic diverticulosis differ among ethnic groups and lifestyles[5,6]; left-sided diverticulosis is most common in Western and developed countries, while right-sided diverticulosis is more prevalent in Asian and developing countries[4,7,8].

Although some data on colonic diverticulosis from Asian countries are available[6,9,10], information on colonic diverticulosis in the region of Southeast Asia is limited and outdated[11]. As the characteristics of colonic diverticulosis have changed with time[12,13], this study aimed to determine the pattern and distribution of colonic diverticulosis in Thai adults in recent years.

After obtaining approval from our Institutional Review Board (SIRB 634/2554), a review of the computerized radiology database for DCBE in Thai adults (defined as individuals aged ≥ 18 years) was performed at the Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. All findings of colorectal lesions detected at DCBE from June 2009 to October 2011 were analyzed. Incomplete studies, e.g. patients who were unable to hold barium or DCBE performed in patients with colonic obstruction, were excluded. Barium studies in non-Thai individuals were also excluded. Written informed consent was given by all patients before undergoing fluoroscopic DCBE. The detailed techniques and interpretation of standard fluoroscopic DCBE performed in our institute were previously reported[14]. Briefly, DCBE demonstrates a diverticulum as a barium-filled outpouching of the colon which is joined to the colonic wall by a neck. The DCBE findings were interpreted and reported by a staff gastrointestinal radiologist.

Patients’ characteristics, indication for DCBE, and anatomical distribution of colonic diverticula were analyzed. In this study, the colon was divided into 3 parts: the right-sided colon (the cecum, the ascending colon, and the hepatic flexure of the colon), the transverse colon, and the left-sided colon (the splenic flexure of the colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the rectum). Right colonic diverticulosis was defined as a diverticulum, or diverticula, detected on DCBE in the right-sided colon regardless of the involvement of the remaining colon. Left colonic diverticulosis was defined as a diverticulum, or diverticula, detected on DCBE in the left-sided colon regardless of the involvement of the remaining colon. The presence of diverticula in all three colonic segments was defined as pancolonic diverticulosis. Of note, a rectal diverticulum was defined as a diverticulum found below the imaginary line between the sacral promontory and the pubic symphysis on the lateral pelvic view of DCBE. A giant diverticulum was defined as a diverticulum demonstrated on DCBE with a diameter of ≥ 4 cm.

All data were prepared and compiled using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences program version 11.3 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). The prevalence and distribution of colonic diverticulosis detected at DCBE were analyzed with 95%CI analysis for Windows (Statistics with Confidence, 2nd Edition, BMJ Books, London 2000). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the prevalence of diverticulosis between gender, and between symptomatic patients and asymptomatic individuals. Of note, asymptomatic individuals were defined as those without any gastrointestinal tract symptoms. The correlation between age and the presence of colonic diverticular disease was analyzed using a regression analysis. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

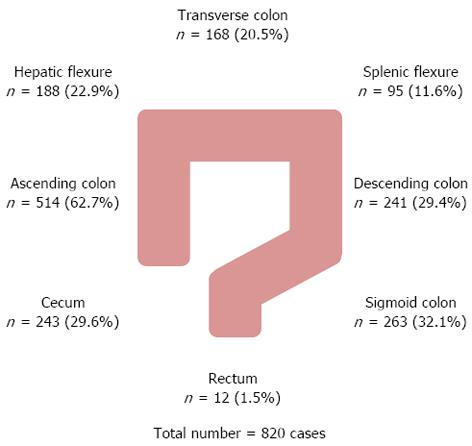

A total of 2877 suitable DCBE examinations were retrospectively reviewed. The mean age of patients was 59.8 ± 14.7 years (range 18-100 years). Of these patients, 1778 (61.8%) were female and 700 (24.3%) were asymptomatic. Colonic diverticulosis was identified on DCBE in 820 patients (28.5%). Right-sided diverticulosis (641 cases; 22.3%) was more frequently found than left-sided diverticulosis (383 cases; 13.3%). Pancolonic diverticulosis and solitary cecal diverticulum were found in 98 cases (3.4%) and 42 cases (1.5%), respectively (Table 1). Rectal diverticulum was seen in 12 cases (0.4%), and it was exclusively associated with the presence of sigmoid diverticulosis. A giant sigmoid diverticulum was demonstrated on DCBE in one case (0.03%). Figure 1 shows the distribution of diverticulosis stratified by colonic segment. Besides colonic diverticula, other major findings included 25 advanced adenomas (0.87%), 76 colorectal cancers (2.64%; 18 in the right-sided colon, 28 in the left-sided colon and 30 in the rectum), and 4 ileocecal Crohn’s disease (0.14%).

| Location | No. of cases | Percentage of total 820 colonic diverticulosis | Percentage of total 2877 DCBEs studied (95%CI) |

| Right-sided only1 | 383 | 46.7 | 13.3 (12.1-14.6) |

| Left-sided only | 153 | 18.7 | 5.3 (4.6-6.2) |

| Transverse only | 10 | 1.2 | 0.3 (0.2-0.6) |

| Extended right-sided (right + transverse) | 44 | 5.4 | 1.5 (1.1-2.0) |

| Extended left-sided (left + transverse) | 16 | 2.0 | 0.6 (0.3-0.9) |

| Bilateral (right + left) | 116 | 14.1 | 4.0 (3.4-4.8) |

| Pancolonic (right + transverse + left) | 98 | 12.0 | 3.4 (2.8-4.1) |

| Total | 820 | 100 | 28.5 (26.9-30.2) |

| Right colonic diverticulosis | 641 | 78.2 | 22.3 (20.8-23.8) |

| Left colonic diverticulosis | 383 | 46.7 | 13.3 (12.1-14.6) |

| Transverse colonic diverticulosis | 168 | 20.5 | 5.8 (5.0-6.8) |

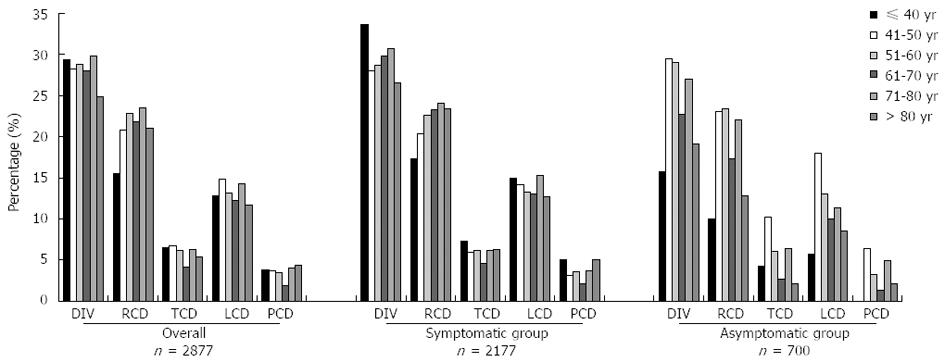

There was no significant difference in the occurrence of colonic diverticulosis between male and female patients (28.3% vs 28.6%, P = 0.85). However, DCBE examinations performed in patients with some gastrointestinal symptoms revealed the frequent occurrence of colonic diverticulosis compared with those performed in asymptomatic individuals (29.5% vs 25.3%; P = 0.03). Change in bowel habit was strongly associated with the presence of diverticulosis (RR = 1.39, 95%CI: 1.14-1.70, P = 0.005), whereas patients with abdominal pain, constipation and bleeding per rectum had a non-significant increased risk for colonic diverticulosis. The presence of diverticulosis was not significantly correlated with age in symptomatic patients (P = 0.62) or asymptomatic persons (P = 0.52) (Figure 2).

In this study, colonic diverticulosis was identified in nearly 30% of DCBE examinations performed in Thai adults. Right-sided diverticulosis was found more frequently than left-sided diverticulosis. Our findings of colonic diverticulosis are consistent with other observations; in which right-sided colonic diverticulosis is most commonly involved in Asians, whereas sigmoid diverticulosis predominates in Western populations[6,7,15]. Compared with a previous hospital-based study of colonic diverticulosis in Bangkok in the 1980s[11], the present study revealed a markedly higher rate of this condition, but a similar proportion of disease in relatively young individuals. It is difficult to explain why there is a relatively high frequency of colonic diverticulosis in young Thai adults. It is possible that, apart from some differences in dietary intake and lifestyle, racial and genetic predisposition could play an important role in the development of colonic diverticulosis[16]. Apparently, genetic influences on the development of diverticulosis in Asian populations have a stronger impact than those in Western populations, especially for right-sided colonic diverticulosis[17].

Moreover, we found no significant difference in the rate of colonic diverticulosis detected by DCBE between genders, which is consistent with several recent reviews of the literature[8,17,18]. However, there have been a few reports of an increased risk of colonic diverticulosis in males[19,20]. In addition, we did not identify a significant correlation between the presence of diverticulosis and age. Notably, the frequency of pancolonic diverticulosis in our study was 3.4%, which was fairly constant among the different age groups. In contrast to these findings, many authors have repeatedly reported that the prevalence of diverticulosis increases with age[4,21,22]. An interesting study by Takano et al[13] also showed that diverticulosis progressed with time from the proximal colon to the distal colon. Although the prevalence and extent of colonic diverticulosis is largely age-dependent, its widespread appearance in the Asian population could be as early as adolescence[20] with peak prevalence at the age of 50-60 years[10]. This could, in part, explain our findings of a relatively high rate of colonic diverticulosis in fairly young age groups; therefore, we did not identify a significant increment in colonic diverticulosis in advanced age groups.

With regard to cecal diverticulosis which involves multiple lesions, we found 42 cases of solitary cecal diverticulum; accounting for 1.5% of all DCBEs studied. Solitary cecal diverticulum is a fairly rare and asymptomatic lesion unless it becomes hemorrhagic or inflamed (mimicking acute appendicitis). Its incidence in Asian populations seems higher than that in Western populations[10,23]. We also identified 12 cases (0.4%) of rectal diverticulum which was exclusively associated with the presence of sigmoid diverticulosis. The true incidence and pathogenesis of rectal diverticulum remain unknown as it is rarely reported[24]. As such lesions were present together with sigmoid colon diverticula, rectal and sigmoid diverticulosis may share the same pathogenesis.

More interestingly, we found a single 5-cm diverticulum in the sigmoid colon in a 51-year-old healthy male. The giant diverticulum was first described in 1946, and to date, fewer than 200 cases have been reported in the literature[25,26]. It is mainly found in the sigmoid colon, and can be divided into 3 distinct histological types: true diverticulum, false diverticulum, and pseudo-diverticulum (scar tissue without any colonic wall layer)[27]. Management of a giant diverticulum depends on the patient’s symptoms and underlying disease. Diverticulectomy or segment resection of the affected colon is the favored choice of treatment in symptomatic patients.

Lastly, we demonstrated that the DCBE examinations performed in patients with some gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., bowel habit change, constipation, abdominal pain and hematochezia) revealed a higher prevalence of colonic diverticulosis than those performed in asymptomatic individuals. It is obvious that many patients with colonic diverticulosis experience chronic gastrointestinal symptoms at some time in their life[28]. However, it is difficult to know whether colonic diverticulosis is a cause or a result of such symptoms.

In conclusion, the present study examined the frequency and distribution of colonic diverticulosis from a relatively large number of fluoroscopic DCBEs performed in Thai adults. Colonic diverticulosis was identified in nearly 30% of DCBE examinations. Right-sided diverticulosis was more common than left-sided diverticulosis. There was no association between the presence of diverticulosis and gender or age. Colonic diverticulosis was more commonly reported in patients with some gastrointestinal symptoms, especially those with change in bowel habit.

Colonic diverticulosis is a common gastrointestinal condition. The prevalence and distribution of colonic diverticulosis differ among ethnic groups and lifestyles; left-sided diverticulosis is more common in Western and developed countries, while right-sided diverticulosis is more prevalent in Asian and developing countries. Moreover, the characteristics of colonic diverticulosis have changed over time.

Although some data on colonic diverticulosis from Asian countries are available, the information on colonic diverticulosis in Southeast Asia is limited and some are outdated. Double contrast barium enema (DCBE) is a reliable investigation tool for demonstrating the presence and extent of colonic diverticulosis.

This paper demonstrates that colonic diverticulosis was identified in 28.5% of DCBEs performed in Thai adults. Right-sided diverticulosis was more common than left-sided diverticulosis. Pancolonic diverticulosis was found in 3.4% of patients. There was no association between the presence of diverticulosis and gender or age, however, DCBE examinations performed in patients with some gastrointestinal symptoms revealed the frequent occurrence of colonic diverticulosis compared with those performed in asymptomatic individuals. Change in bowel habit was strongly associated with the presence of diverticulosis.

The study results show that the occurrence of colonic diverticulosis in Thailand, a developing country in Asia, is surprisingly prominent and markedly higher than that previously reported from a hospital survey in Bangkok approximately 30 years ago. In addition, the rate of colonic diverticulosis in the present study was equal in the different age groups i.e., its widespread appearance could be seen as early as adolescence. These findings may urge physicians to include or consider colonic diverticular disease as one of the causes of gastrointestinal symptoms in every patient, including young individuals.

Colonic diverticulosis is usually described as the presence of outpouching(s) of the mucosa and submucosa through a weak area of the large intestine. When a diverticulum (or multiple diverticula) becomes symptomatic, infected or bleeding, this gastrointestinal condition may be called “colonic diverticular disease”.

This is a good descriptive study in which authors analyze the pattern and distribution of colonic diverticulosis from a third world country, where the frequency of such a condition is expected to be low. In fact, this study showed an unexpectedly high number of colonic diverticulosis in Thai adults. The distribution of colonic diverticulosis is brilliantly shown in great details. The results are also interesting and suggest that colonic diverticulosis can be seen in adolescence as well as it occurrence is not age-dependent. Some findings are different from those shown in Western populations.

P- Reviewers: Buzas GM, Perakath B S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Maykel JA, Opelka FG. Colonic diverticulosis and diverticular hemorrhage. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;17:195-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Humes D, Smith JK, Spiller RC. Colonic diverticular disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:1163-1164. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Halligan S, Saunders B. Imaging diverticular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:595-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kang JY, Melville D, Maxwell JD. Epidemiology and management of diverticular disease of the colon. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:211-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kang JY, Dhar A, Pollok R, Leicester RJ, Benson MJ, Kumar D, Melville D, Neild PJ, Tibbs CJ, Maxwell JD. Diverticular disease of the colon: ethnic differences in frequency. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:765-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rajendra S, Ho JJ. Colonic diverticular disease in a multiracial Asian patient population has an ethnic predilection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:871-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jun S, Stollman N. Epidemiology of diverticular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:529-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Stollman N, Raskin JB. Diverticular disease of the colon. Lancet. 2004;363:631-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goenka MK, Nagi B, Kochhar R, Bhasin DK, Singh A, Mehta SK. Colonic diverticulosis in India: the changing scene. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1994;13:86-88. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Miura S, Kodaira S, Shatari T, Nishioka M, Hosoda Y, Hisa TK. Recent trends in diverticulosis of the right colon in Japan: retrospective review in a regional hospital. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1383-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vajrabukka T, Saksornchai K, Jimakorn P. Diverticular disease of the colon in a far-eastern community. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:151-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fong SS, Tan EY, Foo A, Sim R, Cheong DM. The changing trend of diverticular disease in a developing nation. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:312-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Takano M, Yamada K, Sato K. An analysis of the development of colonic diverticulosis in the Japanese. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2111-2116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lohsiriwat V, Prapasrivorakul S, Suthikeeree W. Colorectal cancer screening by double contrast barium enema in Thai people. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1273-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chan CC, Lo KK, Chung EC, Lo SS, Hon TY. Colonic diverticulosis in Hong Kong: distribution pattern and clinical significance. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:842-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Commane DM, Arasaradnam RP, Mills S, Mathers JC, Bradburn M. Diet, ageing and genetic factors in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2479-2488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martel J, Raskin JB. History, incidence, and epidemiology of diverticulosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1125-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, Spiegel BM. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1486-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kopylov U, Ben-Horin S, Lahat A, Segev S, Avidan B, Carter D. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and the risk of development of colonic diverticulosis. Digestion. 2012;86:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee YS. Diverticular disease of the large bowel in Singapore. An autopsy survey. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:330-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Comparato G, Pilotto A, Franzè A, Franceschi M, Di Mario F. Diverticular disease in the elderly. Dig Dis. 2007;25:151-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Song JH, Kim YS, Lee JH, Ok KS, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Moon JS. Clinical characteristics of colonic diverticulosis in Korea: a prospective study. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ruiz-Tovar J, Reguero-Callejas ME, González Palacios F. Inflammation and perforation of a solitary diverticulum of the cecum. A report of 5 cases and literature review. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2006;98:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Piercy KT, Timaran C, Akin H. Rectal diverticula: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1116-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mahamid A, Ashkenazi I, Sakran N, Zeina AR. Giant colon diverticulum: rare manifestation of a common disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:331-332. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Toiber-Levy M, Golffier-Rosete C, Martínez-Munive A, Baquera J, Stoppen ME, D’Hyver C, Quijano-Orvañanos F. Giant sigmoid diverticulum: case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:581-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Nano M, De Simone M, Lanfranco G, Bronda M, Lale-Murix E, Aimonino N, Anselmetti GC. Giant sigmoid diverticulum. Panminerva Med. 1995;37:44-48. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome is associated with diverticular disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:652-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |