Published online Dec 14, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8696

Revised: September 17, 2013

Accepted: September 29, 2013

Published online: December 14, 2013

Processing time: 198 Days and 21.5 Hours

AIM: To allow the identification of high-risk postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) patients with special reference to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification.

METHODS: Between 1997 and 2010, 1341 consecutive patients underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer at the Department of Digestive Surgery, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Japan. Based on the preoperative diagnosis, total or distal gastrectomy and sufficient lymphadenectomy was performed, mainly according to the Japanese guidelines for the treatment of gastric cancer. Of these, 35 patients (2.6%) were diagnosed with Grade B or C POPF according to the ISGPF classification and were treated intensively. The hospital records of these patients were reviewed retrospectively.

RESULTS: Of 35 patients with severe POPF, 17 (49%) and 18 (51%) patients were classified as Grade B and C POPF, respectively. From several clinical factors, the severity of POPF according to the ISGPF classification was significantly correlated with the duration of intensive POPF treatments (P = 0.035). Regarding the clinical factors to distinguish extremely severe POPF, older patients (P = 0.035, 65 years ≤vs < 65 years old) and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF (P = 0.007, < 1400/mm3vs 1400/mm3≤) were significantly correlated with Grade C POPF, and a low lymphocyte count was an independent risk factor by multivariate analysis [P = 0.045, OR = 10.45 (95%CI: 1.050-104.1)].

CONCLUSION: Caution and intensive care are required for older POPF patients and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF.

Core tip: Although several possible risk factors associated with the occurrence of postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) have been reported, there have been no generally accepted risk factors to predict POPF changing into extremely severe POPF. In this study, we demonstrated that older patients (P = 0.035) and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF (P = 0.007) were significantly associated with extremely severe International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula grade C POPF, and a low lymphocyte count was identified as an independent risk factor by multivariate analysis (P = 0.045, OR = 10.45).

- Citation: Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Kashimoto K, Kubota T, Okamoto K, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Otsuji E. Risk factors to predict severe postoperative pancreatic fistula following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(46): 8696-8702

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i46/8696.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8696

Recent advances in less invasive treatment techniques and the perioperative management of gastric cancer have decreased the mortality and morbidity rates associated with this disease[1,2]. However, postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is still a major complication following gastrectomy. Once POPF develops, it sometimes contributes to lethal complications, such as abdominal abscesses, secondary anastomotic leakage, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage.

Many surgeons have previously reported several possible risk factors for the occurrence of POPF. It has been reported that the incidence of POPF associated with surgical procedures is higher following radical or extended lymphadenectomy[3,4], splenectomy, or pancreaticosplenectomy[5-7]. Host-related factors on POPF have also been clarified, in which the occurrence of POPF has been significantly correlated with a higher body mass index (BMI) and visceral fat area (VFA), being male, hyperlipidemia, and comorbidities[8-11].

Thus, to decrease the incidence of POPF, several clinical studies have been performed with the aims of avoiding unnecessary surgery and standardizing surgical procedures[4,12]. Moreover, in order to lower the risk of tissue damage and make surgical procedures easier, surgical devices such as ultrasonic activated coagulating scalpels have been developed and most surgeons are currently cautious of the risk factors associated with POPF. However, to date, after patients develop POPF, there are no generally accepted risk factors to predict the change to severe POPF in these patients. Indeed, indicators that provide an objective description of the patient’s condition at specific points in the disease process of POPF are useful to improve understanding of the complications that may be encountered.

In this study, we confirmed that the severity of POPF according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification was correlated with the duration of intensive POPF treatments. Furthermore, we clarified an independent risk factor to predict the worst outcome of POPF treatment with special reference to the ISGPF classification.

Between 1997 and 2010, 1341 consecutive patients underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer at the Department of Digestive Surgery, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine. Of these, 35 patients (2.6%) were diagnosed with severe POPF and were treated intensively. Patients underwent preoperative assessments including gastric endoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scans, and laboratory tests. Based on the preoperative diagnosis, total or distal gastrectomy and sufficient lymphadenectomy was performed, mainly according to the Japanese guidelines for the treatment of gastric cancer[13]. Patients with T1 and N0 tumors underwent D1, D1 + α, or D1 + β lymphadenectomy. Patients with T2 or more advanced tumors and those with N1 or more advanced tumors underwent D2 lymphadenectomy. Briefly, D1 lymphadenectomy indicated dissection of the perigastric lymph nodes (nodal stations No. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6) and D1 + α lymphadenectomy indicated dissection of the perigastric lymph nodes and nodes at the base of the left gastric artery (No. 7). D1 + β lymphadenectomy indicated dissection of the perigastric lymph nodes and stations No. 7, 8a (anterosuperior group of the common hepatic artery), and 9 (celiac artery) lymph nodes. In the D2 dissection, the perigastric lymph nodes and all second-tier lymph nodes were completely retrieved. Depending on the location of the tumor, lymphadenectomy was added along the distal side of the splenic artery (No. 11d) and at the splenic hilum (No. 10), together with splenectomy or splenectomy with distal pancreatectomy[14].

POPF was retrospectively defined according to the ISGPF definition[15]: output via an operatively placed drain (or a subsequently placed percutaneous drain) of any measurable volume of drain fluid on or after postoperative day 3, with an amylase content more than 3 times higher than the upper normal serum value. We comprehensively diagnosed POPF according to not only drain amylase (D-AMY) levels, but also changes in the properties of the drain, clinical findings, laboratory data, and imaging findings such as ultrasonography (US) or CT scans. Patients who had no drains or whose drains were removed that developed postoperative fever (< 38 °C), leukocytosis, and peripancreatic fluid collection detected on US or CT scans were also diagnosed with POPF.

POPF was graded according to the ISGPF criteria as follows: grade A had no clinical impact and required no treatment; grade B required a change in management or adjustment in the clinical pathway; and grade C required a major change in clinical management or deviation from the normal clinical pathway and required aggressive clinical intervention. Patients requiring only repositioning of their drains belonged to Grade B POPF. Patients were classified as grade C POPF if US and CT findings showed peripancreatic fluid collection and drains needed to be placed interventionally in order to improve severe clinical data and conditions. In this study, severe POPF were regarded as a clinically significant pancreatic fistula corresponding to grade B and C POPF.

Patients with POPF, which is diagnosed by high D-AMY level and have no abnormal physical finding and laboratory data, could be followed without any treatments. The abdominal drainage tube is normally removed after the D-AMY level has been reduced to a level lower than three times the serum AMY level. Patients with POPF, which is diagnosed by high D-AMY level and have abnormal findings such as fever, abdominal pain and other laboratory data, start to undergo intensive POPF treatments. After emergency CT examination, if the drainage tube position is good, antibiotics, octreotide acetate and total parenteral nutrition should be started. If the fluid drainage tube position is not satisfactory, an additional or alternative drainage tube can be placed into the abnormal fluid cavity by percutaneous CT or ultrasonography-guided technique. Moreover, bacterial infection of drainage fluid and/or the suspicion of it was detected following these POPF treatments. The drainage tube would be changed into an irrigation type drainage tube. Then, continuous irrigation and drainage with saline would be performed. If these series of conservative POPF treatments were not effective, open drainage and debridement for POPF abscess by laparotomy would be performed and the irrigation type drainage tube and an enteral feeding tube would be placed. After that, comprehensive POPF treatments consist of continuous irrigation drainage with saline, antibiotics, octreotide acetate and enteral nutrition.

The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact probability test were performed for categorical variables, while the Student’s t test and Mann-Whitney U test for unpaired data of continuous variables were performed to compare clinicopathological characteristics between the two groups. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the independent risk factors associated with Grade C POPF. Multivariate odds ratio are presented with 95%CI. In all of these analyses, P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 35 patients with severe POPF. The mean patient age was 67.3 years and the male:female ratio was 6:1. More than 80% of patients were male and the incidence of patients with pT3-T4, pStage III-IV, and D2 or more lymphadenectomy was high. Of 35 patients with severe POPF, 17 (49%) and 18 (51%) patients were classified as grade B and grade C POPF, respectively. The median intensive treatment period of POPF was 20 d. Twenty nine patients were diagnosed with POPF by their D-AMY levels and were retrospectively judged to meet the ISGPF criteria. The remaining 6 patients were diagnosed with POPF by their clinical condition, laboratory data, and CT findings because POPF was detected after drain removal.

| Sex | Male | 30 (86) |

| Female | 5 (14) | |

| Age (yr) | mean + SD | 67.3 ± 9.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | mean + SD | 22.1 ± 3.2 |

| pT-stage | T1 | 3 (9) |

| T2 | 11 (31) | |

| T3 | 15 (43) | |

| T4 | 6 (17) | |

| pN-stage | N0 | 10 (29) |

| N1 | 3 (9) | |

| N2 | 9 (26) | |

| N3 | 13 (36) | |

| pStage | I | 6 (17) |

| II | 3 (9) | |

| III | 18 (51) | |

| IV | 8 (23) | |

| Gastrectomy | Distal | 10 (29) |

| Total or others1 | 25 (71) | |

| Splenectomy | Presence | 21 (60) |

| Absence | 14 (40) | |

| Pancreaticosplenectomy | Presence | 12 (34) |

| Absence | 23 (66) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | < D2 | 8 (23) |

| D2 ≤ | 27 (77) | |

| Resection status | R0 | 10 (29) |

| R1 | 15 (42) | |

| R2 | 10 (29) | |

| ISGPF classification | Grade B | 17 (49) |

| Grade C | 18 (51) |

No current standard definition of POPF reflects the duration of intensive treatments according to the severity of POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Therefore, we compared possible clinicopathologic factors and ISGPF classification between short (< 20 d) and long (≥ 20 d) duration intensive treatments (Table 2). The cut off value of each continuous clinical data was decided by a ROC curve. As a result, the severity of POPF according to the ISGPF classification was significantly correlated with the duration of intensive POPF treatments (P = 0.035). There were no significant differences between both groups for other clinicopathologic factors, although POPF after pancreaticosplenectomy was associated with long duration intensive POPF treatments (P = 0.149). Therefore, we confirmed that the ISGPF classification reflects the duration of intensive treatments according to the severity of POPF and is a reliable classification of POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

| Variables | Intensive treatment periods for POPF | 1P value | ||

| < 20 d | 20 d ≤ | |||

| Sex | Male | 10 (83) | 20 (87) | |

| Female | 2 (17) | 3 (13) | 0.827 | |

| Age (yr) | < 65 | 5 (42) | 7 (30) | |

| 65 ≤ | 7 (58) | 16 (70) | 0.772 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 21 | 5 (42) | 6 (27) | |

| 21 ≤ | 7 (58) | 16 (73) | 0.636 | |

| pT-stage | T1 T2 | 3 (25) | 3 (13) | |

| T3 T4 | 9 (75) | 20 (87) | 0.391 | |

| pN-stage | N1 N2 | 5 (42) | 16 (70) | |

| N3 | 7 (58) | 7 (30) | 0.217 | |

| pStage | III | 4 (33) | 5 (22) | |

| III IV | 8 (67) | 18 (78) | 0.736 | |

| Splenectomy | Presence | 7 (58) | 14 (61) | |

| Absence | 5 (42) | 9 (39) | 0.827 | |

| Pancreatico-splenectomy | Presence | 2 (17) | 10 (43) | |

| Absence | 10 (83) | 13 (57) | 0.149 | |

| Lymphadenectomy | < D2 | 2 (17) | 6 (26) | |

| D2 ≤ | 10 (83) | 17 (74) | 0.685 | |

| Resection status | R0 | 5 (42) | 5 (22) | |

| R1 | 4 (33) | 11 (48) | ||

| R2 | 3 (25) | 7 (30) | 0.728 | |

| Blood loss (g) | < 1000 | 3 (25) | 9 (39) | |

| 1000 ≤ | 9 (75) | 14 (61) | 0.476 | |

| Operation time (min) | < 330 | 6 (50) | 11 (48) | |

| 330 ≤ | 6 (50) | 12 (52) | 0.815 | |

| Preoperative Hb (g/dL) | < 10 | 5 (42) | 3 (13) | |

| 10 ≤ | 7 (58) | 20 (87) | 0.091 | |

| Preoperative Alb (g/dL) | ≤ 3.5 | 3 (30) | 6 (29) | |

| 3.5 < | 7 (70) | 15 (71) | 1.000 | |

| 2Lymphocyte counts (/mm3) | < 850 | 5 (42) | 18 (78) | |

| 850 ≤ | 7 (58) | 5 (22) | 0.073 | |

| ISGPF classification | grade B | 9 (75) | 8 (35) | |

| grade C | 3 (25) | 15 (65) | 0.0353 | |

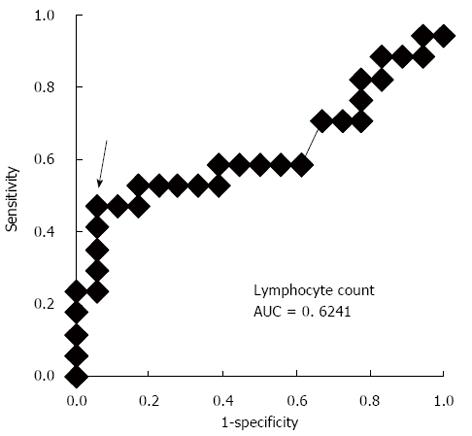

We compared several clinical factors between grade B and C POPF according to the ISGPF classification in order to detect the predictive factors of extremely severe POPF (Table 3). As a result, older patients (P = 0.035, ≤ 65 years old vs < 65 years old) and those with low lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF (P = 0.007, < 1400/mm3vs≥ 1400/mm3) were significantly associated with Grade C POPF. The cut-off value of 1400/mm3 is calculated by the ROC curve to distinguish between grade B and C POPF (Figure 1). The incidence of other clinical factors, which were presented in Table 3 and others such as underlying disease, methods of reconstruction, HbA1c, postoperative Hb, Alb, preoperative serum total protein, total cholesterol, triglyceride, %LVC and FEV 1.0% etc., did not significantly differ between both groups (data not shown). Furthermore, logistic regression analysis revealed that a low lymphocyte count was an independent risk factor by multivariate analysis [P = 0.045, OR = 10.45 (95%CI: 1.050-104.1)] (Table 4).

| Variables | Total | ISGPF classification | 1P value | ||

| Grade B (n = 17) | Grade C (n = 18) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 30 | 14 (82) | 16 (89) | |

| Female | 5 | 3 (18) | 2 (11) | 0.944 | |

| Age (yr) | < 65 | 12 | 9 (53) | 3 (17) | |

| 65 ≤ | 23 | 8 (47) | 15 (83) | 0.0353 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 21 | 13 | 9 (53) | 4 (24) | |

| 21 ≤ | 21 | 8 (47) | 13 (76) | 0.158 | |

| pT-stage | T1 T2 | 6 | 4 (24) | 2 (11) | |

| T3 T4 | 29 | 13 (76) | 16 (89) | 0.402 | |

| pN-stage | N1 N2 | 21 | 9 (53) | 12 (67) | |

| N3 | 14 | 8 (47) | 6 (33) | 0.629 | |

| pStage | III | 9 | 5 (29) | 4 (22) | |

| III IV | 26 | 12 (71) | 14 (78) | 0.921 | |

| Splenectomy | Presence | 21 | 11 (65) | 10 (56) | |

| Absence | 14 | 6 (35) | 8 (44) | 0.836 | |

| Pancreaticosplenectomy | Presence | 12 | 4 (24) | 8 (44) | |

| Absence | 23 | 13 (76) | 10 (56) | 0.344 | |

| Lymphadenectomy | < D2 | 8 | 3 (18) | 5 (28) | |

| D2 ≤ | 27 | 14 (82) | 13 (72) | 0.691 | |

| Resection status | R0 | 10 | 4 (24) | 6 (33) | |

| R1 | 15 | 7(41) | 8 (45) | ||

| R2 | 10 | 6 (35) | 4 (22) | 0.892 | |

| Blood loss (g) | < 1000 | 23 | 11 (65) | 12 (67) | |

| 1000 ≤ | 12 | 6 (35) | 6 (33) | 0.815 | |

| Operation time (min) | < 330 | 19 | 10 (59) | 9 (50) | |

| 330 ≤ | 16 | 7 (41) | 9 (50) | 0.854 | |

| Preoperative Hb (g/dL) | <10 | 8 | 5 (29) | 3 (17) | |

| 10 ≤ | 27 | 12 (71) | 15 (83) | 0.443 | |

| Preoperative Alb (g/dL) | ≤ 3.5 | 9 | 4 (27) | 5 (29) | |

| 3.5 < | 23 | 11 (74) | 12 (71) | 0.825 | |

| 2Lymphocyte counts (/mm3) | < 1400 | 26 | 9 (53) | 17 (94) | |

| 1400 ≤ | 9 | 8 (47) | 1 (6) | 0.0073 | |

| Covariate | OR | 95% Confidence limit | P value |

| Lymphocyte counts (/mm3) | |||

| < 1400 vs 1400 ≤ | 10.45 | 1.05-104.1 | 0.045 |

| Age (yr) | |||

| 65 ≤vs < 65 | 3.39 | 0.602-1.886 | 0.166 |

Until recently, there has been no universally recognized definition of POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Accordingly, different definitions of POPF have been reported, which has resulted in highly variable rates of POPF, ranging from 5.8% to 49.7%[7,10,16-20]. Therefore, it is impossible to accurately evaluate the incidence and severity of POPF. Obama et al[21] were the first to utilize the ISGPF classification, which was formulated as an objective definition of POPF following pancreatic surgery in 2005[15], to evaluate the feasibility of laparoscopic gastrectomy with radical lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. The incidence of ISGPF grade B or C including both open and laparoscopic gastrectomy was 5.1% (12/233)[21]. Miki et al[22] also reported using the ISGPF classification that a high content of drain AMY on 1POD could be used to predict severe POPF. The incidence of ISGPF grade B or C following total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy was 22.1% (23/104). Jiang et al[11] recently reported that severe POPF, defined as ISGPF grade B or C, was associated with being male and a high BMI in patients undergoing laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer. The incidence of ISGPF grade B or C following laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer was 4.2% (34/798). Miyai et al[23] advocated that simple predictive scoring system might be useful for many clinicians to assess the risk of POPF after laparoscopic gastrectomy (LAG). The incidence of ISGPF grade B or C following LAG was 3.9% (11/277). These reports clarified the significance of using the same definition of POPF and detecting the risk factors of POPF using the ISGPF classification. However, it remains unclear whether the ISGPF classification following pancreatic surgery can be applied to POPF following gastrectomy to reflect the extent of the severity of POPF and treatment outcomes.

In order to elucidate whether the ISGPF classification can be translated into a clinically useful definition for POPF following gastrectomy, we showed that differences in the severity of POPF defined by the ISGPF classification indeed reflected intensive treatment periods. As a result, we confirmed that the ISGPF classification was a reliable classification that was significantly correlated with the duration of intensive treatments in patients with severe POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer (Table 1). These results contribute to universal recognition of the ISGPF classification as one of the candidate definitions of POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer.

Although several possible risk factors associated with the occurrence of POPF have been reported, there have been no generally accepted risk factors to predict extremely severe POPF, which requires several intensive treatments. During intensive treatments, indicators that provide an objective description of the patient’s condition at the diagnosis of POFP are useful for understanding the complications that may be encountered. In this study, we demonstrated that older patients (P = 0.035) and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF (P = 0.007) were significantly associated with extremely severe grade C POPF, and a low lymphocyte count was identified as an independent risk factor by multivariate analysis (P = 0.045, OR = 10.45) (Table 2).

At first, we hypothesized that there were some differences among the previously reported risk factors associated with the occurrence of POPF between grade B and C in patients with severe POPF. However, contrary to our expectations, there was no correlation with the previously reported factors associated with the occurrence of POPF such as radical or extended lymphadenectomy[3,4], splenectomy or pancreaticosplenectomy[5-7], a higher BMI and VFA, being male, hyperlipidemia, and comorbidities[8-11]. In this study, blood lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF were the only independent risk factor to predict the severity of POPF patients. This result implies that factors associated with the occurrence of POPF may not affect the severity of severe POPF by changing it from grade B to C POPF.

The reason why a low lymphocyte count was the only independent risk factor to predict extremely severe POPF remains unclear. One possible reason is that a change in the severity of POPF from grade B to C POPF may be associated with host-related immunity. Hogan et al[24] suggested that a perioperative reduction in circulating lymphocyte levels was an independent predictive factor for wound complications following excisional breast cancer surgery. As discussed in their report, which resulted in selective antibiotic prophylaxis being required for these immune-compromised patients, POPF patients with lower lymphocyte counts at diagnosis may require more intensive treatments to avoid POPF developing into extremely severe POPF, such as grade C POPF. Another possible reason was that a low lymphocyte count may be caused by a delay in the diagnosis of severe POPF and this data may reflect a pre-septic state[25,26]. Patients with POPF, which have only abnormal D-AMY data, can be followed without any treatment. These patients mainly resulted in grade A POPF; however, some of these patients may later develop severe POPF. Indeed, in our study, severe POPF patients with grade B started intensive treatments after an average of 5.7 d. In contrast, extremely severe POPF patients with grade C started these treatments after an average of 10.3 d (data not shown). Severe POPF sometimes presents no clinical symptoms such as high grade fever and abdominal pain until some time later. However, surgeons should bear in mind that some POPF patients may develop extremely severe POPF. Therefore, a lower lymphocyte count could provide an objective description and is useful for understanding the complications that may be encountered.

In conclusion, we confirmed that the ISGPF classification of POPF following gastrectomy was a reliable classification that correlated with the duration of intensive treatments in patients with severe POPF. Furthermore, we clarified an independent risk factor to predict the worst outcome of POPF treatment with special reference to the ISGPF classification. Therefore, caution and intensive care are required for older POPF patients and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF.

Despite recent advances in less invasive treatment techniques and the perioperative management of gastric cancer, postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) is still a major complication following gastrectomy. Once POPF develops, it sometimes contributes to lethal complications, such as abdominal abscesses, secondary anastomotic leakage, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage. However, to date, after patients develop POPF, there are no generally accepted risk factors to predict these patients to change severe POPF.

Indicators that provide an objective description of the patient’s condition at specific points in the disease process of POPF are useful to improve understanding of the complications that may be encountered. In this study, the authors confirmed that the severity of POPF according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification was correlated with the duration of intensive POPF treatments. Furthermore, they clarified an independent risk factor to predict the worst outcome of POPF treatment with special reference to the ISGPF classification.

Between 1997 and 2010, 1341 consecutive patients underwent gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Of these, 35 patients (2.6%) were diagnosed with Grade B or C POPF according to the ISGPF classification and were treated intensively. The severity of POPF according to the ISGPF classification was significantly correlated with the duration of intensive POPF treatments (P = 0.035). Regarding the clinical factors to distinguish extremely severe POPF, older patients (P = 0.035, ≥ 65 years old vs < 65 years old) and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF (P = 0.007, < 1400/mm3vs≥ 1400/mm3) were significantly correlated with Grade C POPF, and a low lymphocyte count was an independent risk factor by multivariate analysis [P = 0.045, OR = 10.45 (95%CI: 1.050-104.1)].

The ISGPF classification of POPF following gastrectomy was a reliable classification that correlated with the duration of intensive treatments in patients with severe POPF. Caution and intensive care are required for older POPF patients and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF.

POPF: POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer is still a major complication following gastrectomy. ISGPF: grade A had no clinical impact and required no treatment; grade B required a change in management or adjustment in the clinical pathway; and grade C required a major change in clinical management or deviation from the normal clinical pathway and required aggressive clinical intervention.

This is a good descriptive study showing that the ISGPF classification was reliable in patients with POPF following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Caution and intensive care are required for older POPF patients and those with lower lymphocyte counts at the diagnosis of POPF.

P- Reviewers: Nakano H, Ochiai T, Yoshikawa T S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Degiuli M, Sasako M, Ponti A. Morbidity and mortality in the Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group randomized clinical trial of D1 versus D2 resection for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:643-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Katai H, Sasako M, Fukuda H, Nakamura K, Hiki N, Saka M, Yamaue H, Yoshikawa T, Kojima K. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with suprapancreatic nodal dissection for clinical stage I gastric cancer: a multicenter phase II trial (JCOG 0703). Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:238-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bonenkamp JJ, Songun I, Hermans J, Sasako M, Welvaart K, Plukker JT, van Elk P, Obertop H, Gouma DJ, Taat CW. Randomised comparison of morbidity after D1 and D2 dissection for gastric cancer in 996 Dutch patients. Lancet. 1995;345:745-748. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, Hiratsuka M, Tsujinaka T, Kinoshita T, Arai K, Yamamura Y. Gastric cancer surgery: morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para-aortic lymphadenectomy--Japan Clinical Oncology Group study 9501. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2767-2773. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Otsuji E, Yamaguchi T, Sawai K, Okamoto K, Takahashi T. Total gastrectomy with simultaneous pancreaticosplenectomy or splenectomy in patients with advanced gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1789-1793. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kunisaki C, Makino H, Suwa H, Sato T, Oshima T, Nagano Y, Fujii S, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Otsuka Y. Impact of splenectomy in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma of the cardia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1039-1044. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Nobuoka D, Gotohda N, Konishi M, Nakagohri T, Takahashi S, Kinoshita T. Prevention of postoperative pancreatic fistula after total gastrectomy. World J Surg. 2008;32:2261-2266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kunisaki C, Makino H, Takagawa R, Sato K, Kawamata M, Kanazawa A, Yamamoto N, Nagano Y, Fujii S, Ono HA. Predictive factors for surgical complications of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2085-2093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katai H, Yoshimura K, Fukagawa T, Sano T, Sasako M. Risk factors for pancreas-related abscess after total gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:137-141. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Tanaka K, Miyashiro I, Yano M, Kishi K, Motoori M, Seki Y, Noura S, Ohue M, Yamada T, Ohigashi H. Accumulation of excess visceral fat is a risk factor for pancreatic fistula formation after total gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1520-1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jiang X, Hiki N, Nunobe S, Kumagai K, Nohara K, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Postoperative pancreatic fistula and the risk factors of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Sairenji M, Arai K, Kinoshita T, Nashimoto A, Hiratsuka M. Left thoracoabdominal approach versus abdominal-transhiatal approach for gastric cancer of the cardia or subcardia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:644-651. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:1-5. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma. 13th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara Co 1999; . |

| 15. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Sano T, Sasako M, Katai H, Maruyama K. Amylase concentration of drainage fluid after total gastrectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1310-1312. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Furukawa H, Hiratsuka M, Ishikawa O, Ikeda M, Imamura H, Masutani S, Tatsuta M, Satomi T. Total gastrectomy with dissection of lymph nodes along the splenic artery: a pancreas-preserving method. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:669-673. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ichikawa D, Kurioka H, Yamaguchi T, Koike H, Okamoto K, Otsuji E, Shirono K, Shioaki Y, Ikeda E, Mutoh F. Postoperative complications following gastrectomy for gastric cancer during the last decade. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:613-617. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Okabayashi T, Kobayashi M, Sugimoto T, Okamoto K, Matsuura K, Araki K. Postoperative pancreatic fistula following surgery for gastric and pancreatic neoplasm; is distal pancreaticosplenectomy truly safe? Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:233-236. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kunisaki C, Shimada H, Ono H, Otsuka Y, Matsuda G, Nomura M, Akiyama H. Predictive factors for pancreatic fistula after pancreaticosplenectomy for advanced gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:132-137. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Obama K, Okabe H, Hosogi H, Tanaka E, Itami A, Sakai Y. Feasibility of laparoscopic gastrectomy with radical lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: from a viewpoint of pancreas-related complications. Surgery. 2011;149:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Miki Y, Tokunaga M, Bando E, Tanizawa Y, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Evaluation of postoperative pancreatic fistula after total gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy by ISGPF classification. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1969-1976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miyai H, Hara M, Hayakawa T, Takeyama H. Establishment of a simple predictive scoring system for pancreatic fistula after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:585-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hogan BV, Peter MB, Achuthan R, Beaumont AJ, Langlands FE, Shakes S, Wood PM, Shenoy HG, Orsi NM, Horgan K. Perioperative reductions in circulating lymphocyte levels predict wound complications after excisional breast cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2011;253:360-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hotchkiss RS, Osmon SB, Chang KC, Wagner TH, Coopersmith CM, Karl IE. Accelerated lymphocyte death in sepsis occurs by both the death receptor and mitochondrial pathways. J Immunol. 2005;174:5110-5118. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Lang JD, Matute-Bello G. Lymphocytes, apoptosis and sepsis: making the jump from mice to humans. Crit Care. 2009;13:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |