MECHANISMS FAVOURING DIFFERENT STANDARDS

We know that there are endoscopist-dependent variations in colonoscopy performance - whether this service is provided in routine clinics or screening[1-4]. Quality assurance (QA) initiatives driven by health care providers may be half-hearted - particularly when demands for colonoscopy outnumber available capacity and reducing unacceptable waiting lists is first priority. Within the European Union, however, it has been stated explicitly for screening that only organized screening that can be evaluated is to be accepted, “performance indicators should be monitored regularly” and the population should be protected from “poor-quality screening”[5]. Independent of such policy statements for QA which may have its counterparts in clinical non-screening services in many countries, client or patient-driven QA may have a stronger impact in screening programmes than in routine clinics. The option of not attending if the quality is sub-standard is both more realistic and a dreadful threat to screening programmes compared to routine clinical services. Whichever colorectal cancer (CRC) screening method is used, high attendance rates are crucial for the success of any screening programme - “the best screening test is the one that gets done”[6].

There is a basic difference between screening participants and patients. Screenees are presumptively healthy individuals who seek confirmation that they are just that - healthy. Patients have symptoms and disease for which they seek whatever help may be offered. This means that patients may be more willing to accept some risk of complications, harms and discomfort to be cured. It is reasonable that screenees are not willing to subject themselves to risks and discomfort to obtain confirmation of being healthy.

Screening participants: Presumptively healthy seeking confirmation of being healthy. Not willing to take risks to obtain this confirmation. They request documentation of benefits and harms - “what is in it for me?”

Patients: They have symptoms or known disease for which they seek whatever help they may be offered. It may be a matter of clinging to a hope of cure with great willingness to pay and few questions asked on documentation of effect - “please, just do something!”

Since high attendance rates are crucial for screening programmes, it is important to understand the reasons for non-attendance. This is far from a primary issue in routine clinics serving patients. In focus groups addressing CRC screening, both representatives of target populations and family doctors have expressed scepticism to screening, questioning the evidence of its effectiveness[7]. To meet these critics, facts about risks and benefits and defining fields of uncertainty must be produced and made accessible in a trustworthy and understandable format to provide a basis for informed decision-making by members of the target population[8,9]. This is quite a different exercise from campaigning for screening by appealing to fear, guilt and personal responsibility - methods that may have been used too frequently in the short history of screening to improve attendance[10]. Such campaigning will only tear down any trustworthiness there may have been. There should be a strong incitement to provide high-degree level of evidence to support (or discard) screening - evidence that can withstand scepticism and critics generated by poor-level evidence and over-selling screening services[10].

SIZE OF THE PROBLEM AND THE HIGH INTENTIONS OF DOING GOOD

On a worldwide basis, there are more than 1.2 million new cases of CRC diagnosed annually with prospects of 5-year survival for 50%-60% of patients[11,12]. Symptoms often appear late and they are unspecific - mimicking common and more trivial conditions like haemorrhoids and irritable bowel. Although progress is being made on treatment of advanced CRC, new drugs are driving costs, but the best bet for cure remains early diagnosis and surgery. Both to get at the cancer at an early, asymptomatic stage to save lives and suffering - and to save costs for treatment of advanced disease[13], CRC screening is recommended in several countries[14]. There are several screening methods, but only fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) and flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) have been subjected to randomized trials (RCT) with long-term follow-up[15-18]. By intention-to-treat analyses, FOBT screening reduces CRC mortality by 15%-18% with no effect on CRC incidence. FS screening reduces mortality by 28% and incidence by 18%[18]. Intuitively, colonoscopy screening should be twice as good as FS (“half-way colonoscopy”) combining “gold standard” sensitivity for CRC and polyp detection with tissue sampling and removal of CRC precursor lesions (polyps). There are RCTs on colonoscopy underway, but results are not expected for many years[19,20]. Retrospective studies, however, have suggested that colonoscopy screening may not be as effective as expected in reducing right-sided CRC[21]. It has been suggested that right-sided (proximal) sessile serrated polyps, which are easily overlooked and share molecular similarities to CRC, may represent an additional polyp-carcinoma pathway similar to the traditional adenoma-carcinoma pathway[22]. This may explain poorer results than expected for colonoscopy in reducing the burden of right-sided CRC. When the trials on FOBT and FS screening were done, endoscopists and pathologists largely considered sessile serrated polyps to be hyperplastic and non-neoplastic with no intrinsic potential to develop into CRC. Changing to go aggressively for these right-sided sessile lesion has its implications (e.g., higher risk of perforation at polypectomy) and we really do not know what there is to be gained - i.e., we cannot quantify expectations of a reduced risk of CRC.

OVERTREATMENT WITH A FEAR OF NOT DOING ENOUGH

Screening is a neat balance between benefits and harms - benefit for the few (those few discovered to have asymptomatic CRC or advanced adenoma) vs inconvenience and potential risks for the many (all other participants). Providing data on CRC mortality and/or incidence reduction is a prerequisite before implementing screening programmes[5], but the target population should also receive valid information on the downsides of screening, like the risk of perforation and bleeding when polypectomy is recommended. We now have long-term results from RCTs on FOBT and FS screening based on the standards used in the trials, including work-up colonoscopies and surgical treatment, and we can provide the target population with information of what is to be gained in terms of mortality and incidence reduction and the risks involved with endoscopy, polyp removal and surgery when required. This is very much a satisfactory level of practicing “evidence-based medicine”.

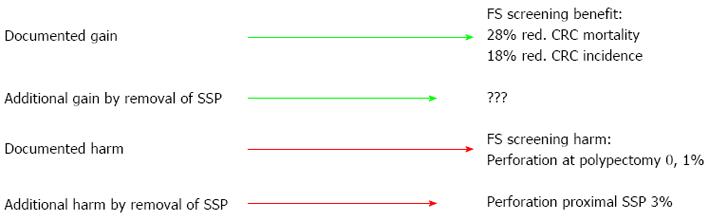

Our current practice of polyp treatment and surveillance is largely based on consensus guidelines. If we change our practice in screening programmes from the standards used in trials preceding the programmes, we do this because we believe such adjustments are for the good. The intentions may be the best, but is the evidence up to standards required for the target population to feel it worthwhile attending for screening? RCTs on FS screening give 18% reduced risk of CRC with a 0.04% risk of perforation and 0.1% risk of perforation at work-up colonoscopy[18]. But - more meticulous search and removal of proximal sessile serrated polyps may involve a risk of 3% for severe complications (perforation and bleeding) for these lesions[23] with no evidence of what to be gained (Figure 1). This is a level of uncertainty that may not be questioned by patients, but more likely tilt the decision of the potential screenee towards not attending.

Figure 1 Overtreatment with a fear of not doing enough.

Introducing uncertainty in the balance between benefits and harms of flexible sigmoidoscopy (FS) screening by adding systematic removal of proximal sessile serrated polyps (SSP) associated with 3% risk of perforation for these lesions[23] and unknown benefit compared to 0.1% risk of perforation[27] and known benefit. CRC: colorectal cancer.

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment of cancer is a recent issue that has emerged from screening activity - not from routine clinical work[24]. For CRC, we know that more than 95% of polypectomies are a waste of time involving unnecessary risks, but we do not know which 5% to go for. After more than 120 years of the adenoma-carcinoma sequence theory[25], we do not know the natural history of adenomas. We can say very little about future risk of CRC in a polypectomized adenoma - had it not been removed. It is desirable with better definition and targeting of high-risk polyps to be removed and low-risk lesions to be ignored at colonoscopy. It is hard to see how this knowledge-gap can be filled without accepting prospective studies on in-situ polyps. With a low risk for complications at polypectomy, this may not be acceptable. Moving towards more aggressive interventions without knowing the magnitude of expected benefit, we may eventually reach a line when screening either is to be stopped or modified due to complications. At that point in time the problems of overtreatment may become so pronounced that in-situ research with all possible security measures may be accepted. There may be more at stake for screening programme providers and participants (screenees) on this issue than for patients, and it may be that comparative effectiveness research (CER) within screening programmes[26] may provide possibilities to fill this and other knowledge-gaps - also for the benefit of clinical practice. Among 45 original publications on the main study and sub-studies published so far from the Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention trial (NORCCAP) there were several findings of transfer value to routine clinical practice - particularly on endoscopy technique and technology (listed in http://www.kreftregisteret.no/norccap).

CONCLUSION

There is a basic difference in incitements to attend for screening when you are healthy and for routine clinics when you are ill. This may be more clearly brought forward by an increasing demand for patients and clients to have a say in QA of health care provisions - both in screening and routine clinics. There are logical mechanisms which may set standards for screening higher than for routine clinics, but this may prove to be of benefit for clinical services and patients in the long run.

P- Reviewers: Amin AI, de Bree E, Meshikhes AWN, Rutegard J S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S