Published online Dec 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8435

Revised: April 19, 2013

Accepted: June 1, 2013

Published online: December 7, 2013

Processing time: 284 Days and 13.7 Hours

Erosive hemorrhage due to pseudoaneurysm is one of the most life-threatening complications after pancreatectomy. Here, we report an extremely rare case of rupture of a pseudoaneurysm of the common hepatic artery (CHA) stump that developed after distal pancreatectomy with en block celiac axis resection (DP-CAR), and was successfully treated through covered stent placement. The patient is a 66-year-old woman who underwent DP-CAR after adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic body cancer. She developed an intra-abdominal abscess around the remnant pancreas head 31 d after the surgery, and computed tomography (CT) showed an occluded portal vein due to the spreading inflammation around the abscess. Her general condition improved after CT-guided drainage of the abscess. However, 19 d later, she presented with melena, and CT showed a pseudoaneurysm arising from the CHA stump. Because the CHA had been resected during the DP-CAR, this artery could not be used as the access route for endovascular treatment, and instead, we placed a covered stent via the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery. After stent placement, cessation of bleeding and anterograde hepatic artery flow were confirmed, and the patient recovered well without any further complications. CT angiography at the 6-mo follow-up indicated the patency of the covered stent with sustained hepatic artery flow. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of endovascular repair of a pseudoaneurysm that developed after DP-CAR.

Core tip: Erosive hemorrhage due to pseudoaneurysm is one of the most life-threatening complications after pancreatectomy. Here, we report an extremely rare case of rupture of a pseudoaneurysm of the common hepatic artery stump that developed after distal pancreatectomy with en block celiac axis resection. The pseudoaneurysm was successfully treated through covered stent placement via the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

- Citation: Sumiyoshi T, Shima Y, Noda Y, Hosoki S, Hata Y, Okabayashi T, Kozuki A, Nakamura T. Endovascular pseudoaneurysm repair after distal pancreatectomy with celiac axis resection. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(45): 8435-8439

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i45/8435.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8435

Erosive hemorrhage due to pseudoaneurysm, concomitant to a pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess, is one of the most serious complications after pancreatectomy[1]. Several recent reports have described the successful endovascular treatment of pseudoaneurysms that may develop after pancreaticoduodenectomy[1,2]. However, there has been no published report of endovascular repair of pseudoaneurysms that develop after distal pancreatectomy with en block celiac axis resection (DP-CAR) because of the difficulty of the endovascular approach associated with resection of the common hepatic artery (CHA) in this procedure. Here, we report an extremely rare case of a successfully treated pseudoaneurysm of the CHA stump that developed after DP-CAR by covered stent placement via the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA). To our knowledge, no similar case has been reported.

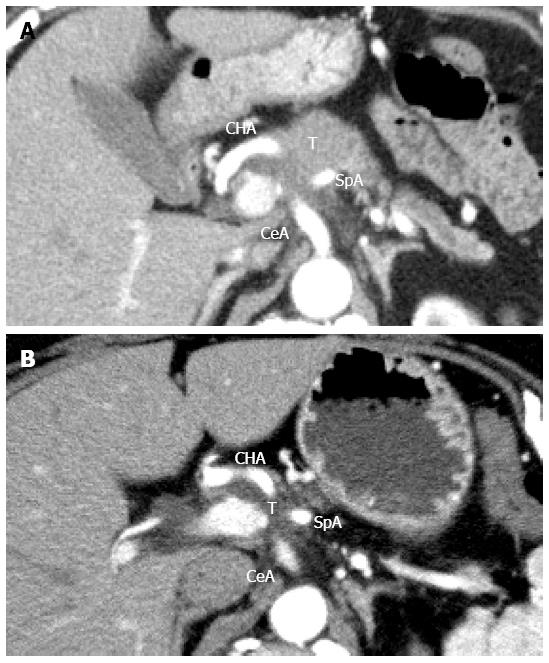

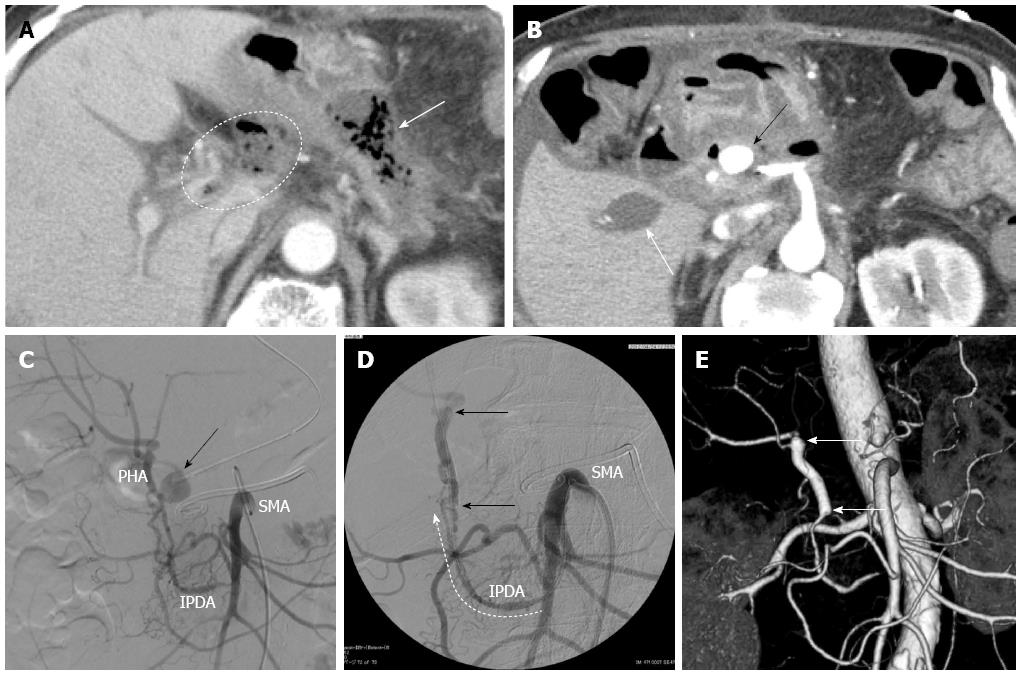

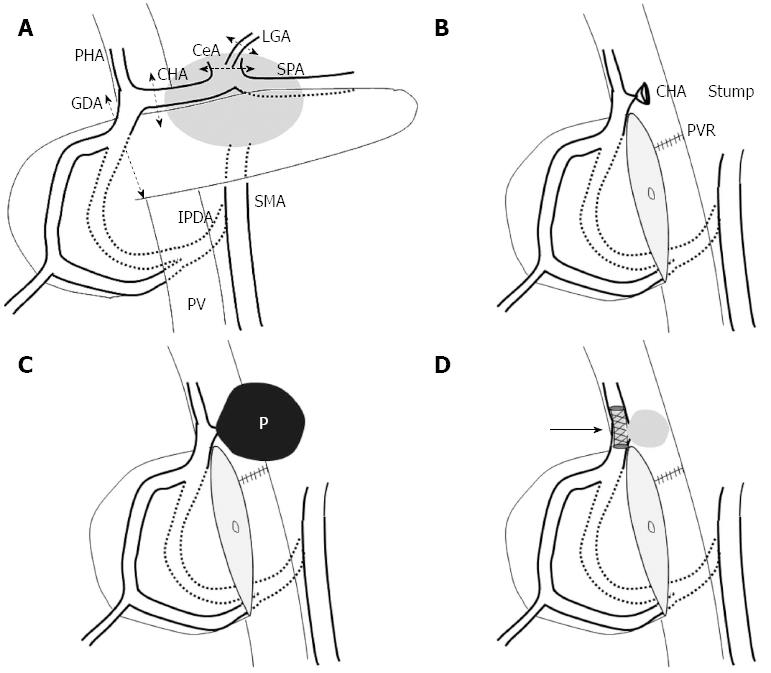

A 66-year-old woman presented with intractable back pain. Laboratory test results showed a high level of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9; 936 U/mL) and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) indicated the presence of a 4.3 cm low-density pancreatic body tumor that involved the CHA, splenic artery (SpA), celiac axis (CeA), and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) (Figure 1A). No distant metastasis was detected. We determined that the tumor was unresectable at that time, and initiated conversion chemoradiation therapy with gemcitabine (1000 mg/body per 2 weeks) and 50 Gy external beam radiation. After the first chemoradiation treatment, the patient received additional gemcitabine chemotherapy (1600 mg/body per 2 weeks) at the discretion of the medical oncologist. After 5 mo of this chemoradiation therapy, the CA 19-9 level had declined to the normal range (14.1 U/mL) and contrast-enhanced CT revealed that the maximum tumor diameter had decreased to 3.0 cm (Figure 1B). Furthermore, although the tumor still involved the CeA, SpA, and CHA, the invasion around the SMA was remarkably diminished. At this point, we determined that the tumor could be completely removed by DP-CAR, and the surgery was planned. At laparotomy, the SMA and the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) were free of tumor invasion. The resectability was confirmed, and the DP-CAR procedure with concomitant portal vein resection was performed. Histopathological examination showed a mucinous carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Portal venous invasion and extrapancreatic perineural invasion were also confirmed; however, the resection margin of the specimen indicated a negative result for cancer (R0). According to the UICC-TNM classification system, the pancreatic tumor was classified as Stage III (T3N1M0). The patient’s intractable back pain disappeared immediately after the surgery, and the postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 13. One week after discharge, she was re-admitted because of appetite loss and oral feeding difficulty. Contrast-enhanced CT at 31 d after surgery showed formation of an intra-abdominal abscess around the remnant pancreas head as well as portal vein occlusion due to the spreading inflammation around the abscess (Figure 2A). CT-guided abscess drainage was performed, and the patient’s general condition improved. However, 19 d after drainage of the abscess, the patient presented with melena, and contrast-enhanced CT showed a pseudoaneurysm arising from the CHA stump (Figure 2B). Emergent angiography also showed the pseudoaneurysm arising from the CHA stump (Figure 2C). Because the CHA had been resected during the distal pancreatectomy, the artery could not be used as the access route for endovascular treatment. Therefore, we performed covered stent placement via the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA) originating from the SMA (Figures 2D and 3) using a Jostent GraftMaster 3.0 mm × 16 mm stent (Abbott Vascular, Chicago, United States). After stent placement, cessation of bleeding and anterograde hepatic artery flow were confirmed. Although the portal vein remained occluded, the maximum values of GOT and GPT only reached 119 U/L and 70 U/L, respectively, on day 5 after stent placement, and the patient recovered well without any further complications. CT angiography at the 6-mo follow-up indicated the patency of the covered stent with sustained hepatic artery flow (Figure 2E). Further, there was no sign of recurrence by 8 mo after DP-CAR.

Perineural invasion of pancreatic body cancer can spread towards the celiac plexus and ganglia directly or via the nerve plexus surrounding the SpA and CHA[3]. Therefore, locally advanced pancreatic body cancer often involves the CHA and/or the celiac axis, and it was often regarded as an unresectable disease. DP-CAR is an operative method that can be adopted in such cases of locally advanced pancreatic body cancer[3,4]. The procedure includes distal panc reatectomy and en block resection of the CHA and the CeA with the surrounding neuroplexus. A drawback of this procedure is that, sufficient blood supply from the IPDA to the liver and stomach can not always be ensured. Angiography is routinely performed before DP-CAR in our institution in order to prevent ischemia-related complications in these organs after the surgery. After balloon occlusion of both the CHA and the left gastric artery (LGA), a superior mesenteric angiogram is obtained. If the angiogram indicates insufficient blood flow of the proper hepatic artery and the right gastroepiploic artery, subsequent coil embolization of both the CHA and the LGA is performed to increase the blood flow in the IPDA and prevent ischemia-related complication after DP-CAR.

With DP-CAR, locally advanced pancreatic body cancers can be resected completely, and some authors have reported prolonged postoperative survival times[3,4]. Hirano et al[3] reported on 23 patients who underwent DP-CAR and described a high R0 resectability rate of 91% with a postoperative mortality rate of 0%. The estimated overall 1- and 5-year survival rates were 71% and 42%, respectively, and the median survival time was 21.0 mo. Baumgartner et al[4] reported on 11 patients who underwent DP-CAR after neoadjuvant therapy. These authors also described an R0 resectability rate of 91%, with a median overall survival of 26 mo.

Although DP-CAR can offer survival benefit and can potentially achieve complete local control in selected patients, the morbidity rate remains very high, ranging from 25% to 80%[5,6]. One of the most serious life-threatening morbidities after pancreatectomy is erosive hemorrhage due to pseudoaneurysm, concomitant to a pancreatic fistula and intra-abdominal abscess[1]. This requires emergent treatment, and the mortality rate of patients who develop intra-abdominal arterial hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is reportedly 20%-50%[7-10]. Takahashi et al[11] successfully treated a case of pseudoaneurysm that developed after DP-CAR using relaparotomy. In their case, as in the current case, the pseudoaneurysm emerged on the stump of the CHA, and resection of the pseudoaneurysm with ligation of the GDA were performed.

In recent years, successful endovascular treatment for pseudoaneurysms that develop after PD has been described, and it is presently believed that endovascular treatment should be a first choice for hemorrhage resulting from the pseudoaneurysm[1,2]. Lee et al[2] reported on 27 patients who developed ruptured pseudoaneurysm after PD. Angiographic procedures for initial hemostasis were technically successful in 25 of the 26 patients who underwent angiography. The procedures for hemostasis included transarterial embolization (TAE) using a microcoil in 21 patients and stent graft in 4 patients. There was no recurrent bleeding in any patient in the group, and the selective microcoil embolization or stent graft procedures were effective for controlling the pseudoaneurysmal bleeding.

Among these endovascular treatments, TAE has been recommended as a first-line treatment, because it has been associated with 83%-100% success rates[2]. However, despite the dual blood supply from the hepatic artery and portal vein, there is a risk of the major complication of liver infarction or abscess after TAE for pseudoaneurysms arising from the hepatic arteries. In the present case, the portal vein was already occluded, and maintaining hepatic artery flow was indispensable in order to avoid hepatonecrosis and concomitant liver failure. Thus, we decided to use a covered stent to maintain hepatic artery flow, and the patient remained free of liver infarction and liver abscess after stent placement. We had to use the arcade of the pancreaticoduodenal artery as the access route for covered stent placement because the CHA had already been resected during the distal pancreatectomy. Although the diameter of the IPDA differs among patients and it is uncertain that the stent can always be successfully delivered via this route, we believe the method is worth attempting after DP-CAR in critical situations such as the one described herein.

P- Reviewers: Hu WM, Nakano H S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Ding X, Zhu J, Zhu M, Li C, Jian W, Jiang J, Wang Z, Hu S, Jiang X. Therapeutic management of hemorrhage from visceral artery pseudoaneurysms after pancreatic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1417-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee JH, Hwang DW, Lee SY, Hwang JW, Song DK, Gwon DI, Shin JH, Ko GY, Park KM, Lee YJ. Clinical features and management of pseudoaneurysmal bleeding after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am Surg. 2012;78:309-317. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Hirano S, Kondo S, Hara T, Ambo Y, Tanaka E, Shichinohe T, Suzuki O, Hazama K. Distal pancreatectomy with en bloc celiac axis resection for locally advanced pancreatic body cancer: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2007;246:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baumgartner JM, Krasinskas A, Daouadi M, Zureikat A, Marsh W, Lee K, Bartlett D, Moser AJ, Zeh HJ. Distal pancreatectomy with en bloc celiac axis resection for locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma following neoadjuvant therapy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1152-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tanaka E, Hirano S, Tsuchikawa T, Kato K, Matsumoto J, Shichinohe T. Important technical remarks on distal pancreatectomy with en-bloc celiac axis resection for locally advanced pancreatic body cancer (with video). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamamoto Y, Sakamoto Y, Ban D, Shimada K, Esaki M, Nara S, Kosuge T. Is celiac axis resection justified for T4 pancreatic body cancer? Surgery. 2012;151:61-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Berge Henegouwen MI, Allema JH, van Gulik TM, Verbeek PC, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Delayed massive haemorrhage after pancreatic and biliary surgery. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1527-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M, Chijiiwa K, Nagakawa T, Imamura M, Takada T. Early and late complications of pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in Japan 1998. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:303-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de Castro SM, Kuhlmann KF, Busch OR, van Delden OM, Laméris JS, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Delayed massive hemorrhage after pancreatic and biliary surgery: embolization or surgery? Ann Surg. 2005;241:85-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, Habermann CR, Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, Kaifi J, Schurr PG, Bubenheim M, Nolte-Ernsting C. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg. 2007;246:269-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Takahashi Y, Kaneoka Y, Maeda A, Isogai M. Distal pancreatectomy with celiac axis resection for carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. World J Surg. 2011;35:2535-2542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |