Published online Dec 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8391

Revised: September 24, 2013

Accepted: October 19, 2013

Published online: December 7, 2013

Processing time: 182 Days and 9.8 Hours

AIM: To investigate the relationships among subtypes of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) using narrow band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopy.

METHODS: A reflux disease questionnaire was used to screen 120 patients representing the three subtypes of GERD (n = 40 for each subtypes): nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux esophagitis (RE) and Barrett’s esophagus (BE). NBI magnifying endoscopic procedure was performed on the patients as well as on 40 healthy controls. The demographic and clinical characteristics, and NBI magnifying endoscopic features, were recorded and compared among the groups. Targeted biopsy and histopathological examination were conducted if there were any abnormalities. SPSS 18.0 software was used for all statistical analysis.

RESULTS: Compared with healthy controls, a significantly higher proportion of GERD patients had increased number of intrapapillary capillary loops (IPCLs) (78.3% vs 20%, P < 0.05), presence of microerosions (41.7% vs 0%, P < 0.05), and a non-round pit pattern below the squamocolumnar junction (88.3% vs 30%, P < 0.05). The maximum (228 ± 4.8 vs 144 ± 4.7, P < 0.05), minimum (171 ± 3.8 vs 103 ± 4.4, P < 0.05), and average (199 ± 3.9 vs 119 ± 3.9, P < 0.05) numbers of IPCLs/field were also significantly greater in GERD patients. However, comparison among groups of the three subtypes showed no significant differences or any linear trend, except that microerosions were present in 60% of the RE patients, but in only 35% and 30% of the NERD and BE patients, respectively (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Patients with GERD, irrespective of subtype, have similar micro changes in the distal esophagus. The three forms of the disease are probably independent of each other.

Core tip: Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been diagnosed with conventional endoscopy and 24-h esophageal pH monitoring. There are three forms of GERD: nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux esophagitis (RE) and Barrett’s esophagus (BE). However, whether GERD is a spectrum of diseases or a “tripartite” disease remains unclear. Using narrow band imaging agnifying endoscopy, we observed no significant differences in the lower esophagus among patients with the three forms of GERD. There was also no increasing trend from NERD, RE to BE, indicating that these subtypes might be independent of each other. Thus, GERD is a “tripartite” disease, rather than a spectrum of diseases.

- Citation: Lv J, Liu D, Ma SY, Zhang J. Investigation of relationships among gastroesophageal reflux disease subtypes using narrow band imaging magnifying endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(45): 8391-8397

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i45/8391.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8391

The montreal definition[1], an evidence-based global consensus definition, has demonstrated that gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common chronic disorder that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications. The prevalence of GERD has been reported to range from 10% to 48% in Asia, slightly lower than that in Western countries[2-4], and is increasing year by year[5-8]. GERD affects seriously patients’ quality of life and poses heavy economic burdens on individuals as well as society because the lack of effective treatment. Unfortunately, the natural history of GERD has not been fully illustrated. Based on the findings of conventional endoscopy and histopathological examination, GERD is generally categorized into three progressive stages: nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux esophagitis (RE), and Barrett’s esophagus (BE). Patients with GERD, according to the current model of GERD as a spectrum disease, could potentially progress from mild NERD toward RE, BE, and then neoplasia[9]. This concept may in fact help the planning of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, as well as the allocation of financial resources. Nevertheless, some researchers disagree, and propose that GERD is a “tripartite” disease. By dividing GERD into the three unique subtypes, physicians or surgeons may concentrate on the specific mechanisms that lead to the development of a subtype of GERD, leading to improvements in the specific therapeutic modalities that benefit the patients with a particular subtype.

Narrow band imaging (NBI) can better capture the microstructures of the superficial mucosa. Recent studies have shown that NBI can reveal subtle changes of esophageal superficial mucosa in GERD patients[10-15]. However, NBI endoscopy has not yet been used to study the microvascular differences among patients with NERD, RE and BE.

The present study aimed to explore the relationships among the three subtypes of GERD by observing the subtle vascular changes detected with NBI magnifying endoscopy. Our study might provide a basis for further diagnosis and treatment of GERD.

Patients with reflux-associated symptoms, who were treated in our hospital between June 2010 and May 2012, were recruited in this study. All the patients were required to fulfill the reflux disease questionnaire (RDQ) concerning their reflux-associated symptoms to decide whether or not NBI magnifying endoscopy would be performed. The inclusion criteria were: aged between 18 and 70 years; ability to provide written informed consent; RDQ score of no less than 12; reflux-related symptom duration of no less than 3 mo; and effective treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). The exclusion criteria included: evidence of cancer or mass lesion in the upper alimentary tract, such as esophageal varices and gastric lesion; severe gastroparesis; history of drug use 4 wk before the study, including PPIs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, antibiotics, antacid, mucosal protective agents, calcium channel blocks and acetylcholine or histamine receptor antagonists; and prior history of upper alimentary surgery, hemorrhage or severe uncontrolled systematic dysfunction. The healthy control group comprised subjects without any gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms and with no positive findings confirmed by conventional endoscopy.

Written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects before endoscopy. The study protocol form was prepared according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Institutional Board of the hospital (No. 2010091).

The NBI magnifying endoscope (Olympus EVLS LUCERA CV-260SL GIF-H260Z) used in this study was purchased from Olympus Medical Systems Corp. (Tokyo, Japan), and permitted a magnification of alimentary mucosa up to 80-fold by zoom and was compatible with an NBI light source in addition to the conventional white light source.

After oral administration of 20 mL (1.0%) dimethicone and 10 mL (0.1 g) oropharyngeal anesthesia agent of dyclonine hydrochloride mucilage, all subjects underwent endoscopic procedure by the same experienced endoscopist who was blind to the GER symptoms. A complete evaluation of the upper alimentary tract was performed under the conventional mode. Then, the distal 5 cm of the esophagus, the squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) and cardia were reexamined carefully with the NBI light source under the maximum magnification of 80-fold. The key point was observation of the superficial vasculature. Images with the microstructure features in these locations were collected during the endoscopy, together with the standardized four-quadrant images from the distal esophagus above the SCJ. An experienced investigator blinded to the GER symptoms evaluated the images.

The diagnostic criteria of NERD were: one or more of the typical reflux-associated symptoms of heartburn, regurgitation and retrosternal pain as chief complaints[1]; absence of mucosal breaks at conventional endoscopy; and effective treatment response to PPIs.

Diagnosis of RE followed the Los Angeles classification[16].

BE was diagnosed when conversion of normal esophageal squamous epithelium to specialized intestinal metaplastic epithelium was confirmed by histopathological examination[1].

Criteria of healthy controls included: no symptoms, no prior history of GERD, RDQ score of 0, and no visible mucosal breaks at conventional endoscopy. If microerosions were detected during the NBI magnifying endoscopy, 24-h pH monitoring was used to exclude asymptomatic GERD.

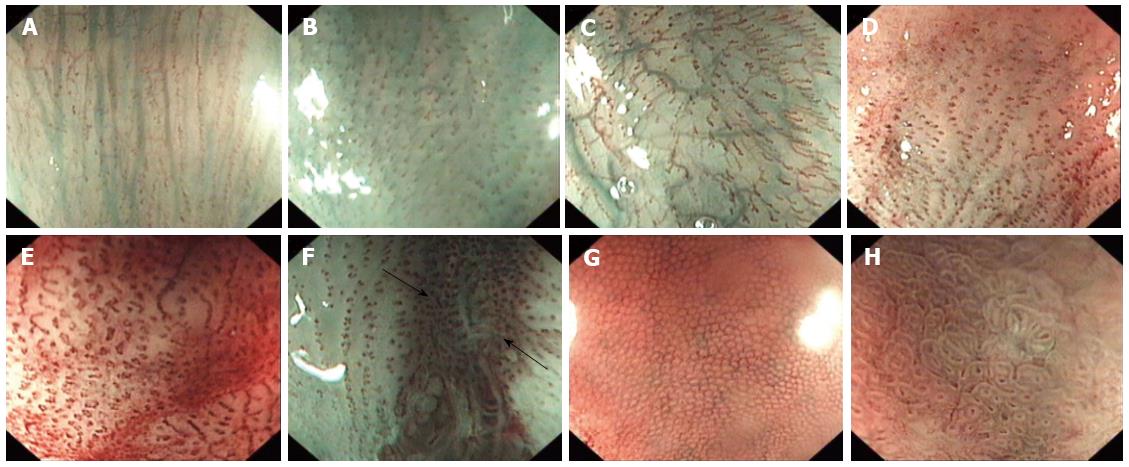

Intrapapillary capillary loops (IPCLs) arise from the submucosal drainage vein and go into the esophageal papillary. Assessment of IPCLs is important in the diagnosis of esophageal disorders. Histopathological examination has revealed that normal IPCLs exist in the esophageal submucosa, and are usually shown as dot-like structures with regular intervals of about 100 μm. The IPCLs in the esophageal mucosa can be readily identified with the help of NBI magnifying endoscopy, under which their morphology is seen to be dynamic and can be affected by neoplasia and inflammation. The morphological changes of IPCLs were defined as follows: (1) Normal IPCLs (Figure 1A): hairpin-like structures with small diameters; (2) Increment (Figure 1B): an increase in the number of IPCLs in individual fields; (3) Prolongation (Figure 1C): a change in the pattern characterized by increased lengths of individual IPCLs; (4) Dilation (Figure 1D): a change in the pattern characterized by increased sizes or calibers of individual IPCLs; (5) Tortuosity (Figure 1E): presence of corkscrewing or the twisted nature of individual IPCLs; (6) Another indicator was microerosion (Figure 1F): mucosal breaks not visible under conventional endoscopy but visible under NBI magnifying endoscopy; (7) Mucosal pit pattern under SCJ was the third indicator. Taking the Endo Classification Criteria as a reference[17], the pit pattern was classified into two categories: round (Figure 1G) and non-round (including straight, oval, tubular and villous pit patterns) (Figure 1H); and (8) Photoshop software (Photoshop CS5 v 8.0; Adobe Inc., United States) was used to edit the image files.

Targeted biopsy was conducted when there was any mucosal lesion, such as erosion. Biopsy samples above and below the SCJ in four quadrants were also taken from all subjects. If esophageal metaplasia was suspected, biopsy sampling was performed in a systematic manner, i.e., four-quadrant biopsies were obtained every 2 cm throughout the affected segment[18]. Histopathological examination was then performed on all the biopsy tissues.

The statistical software SPSS (SPSS PASW Statistics v18 Multilingual-EQUiNOX; SPSS Inc., United States) was used for all statistical analyses. The two-sample t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed on appropriate continuous quantitative variables that were normally distributed to determine whether significant differences existed among groups. Continuous quantitative variables that were not normally distributed were tested using the Wilcoxon test. Categorical variables were analyzed by the χ2 test. Whenever the validity of χ2 was called in question, Fisher’s exact test was used instead. The probability of error (alpha) (P) was set at 0.05. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 157 patients were screened, of whom 145 were eligible for inclusion (40 NERD, 54 RE and 51 BE). To keep a balance among the groups, we selected 40 RE and 40 BE patients randomly. Altogether, we had 120 (66 male, 54 female) patients and 40 healthy controls (16 male, 24 female) included in the final analysis. Among these 120 GERD patients, there were 40 NERD, 40 RE and 40 BE patients. There were no significant differences between healthy controls and GERD patients in terms of gender, age, body mass index (BMI), prevalence of hiatus hernia, and prevalence of bile regurgitation. As for inter-subtype comparison, NERD patients were more likely to be female (P < 0.05), while most of the RE patients were male (P < 0.05). Patients with BE were less likely to demonstrate bile regurgitation (P < 0.05). In addition, the differences were not significant with respect to age, BMI, course, scores of RDQ and prevalence of hiatus hernia. The demographic and clinical characteristics, and conventional observations of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

| HC | GERD | ||||

| GERD | NERD | RE | BE | ||

| Number of subjects | 40 | 120 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Gender (male: female) | 16:24 | 66:54 | 12:28 | 32:8 | 22:18 |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 47.7 ± 2.20 | 52.9 ± 1.09 | 52.2 ± 1.72 | 51.4 ± 1.73 | 55.1 ± 2.17 |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 22.3 ± 0.55 | 23.6 ± 0.36 | 23.5 ± 0.56 | 24.2 ± 0.72 | 23.1 ± 0.60 |

| Mean courses, mo (SD) | - | 26 ± 32.3 | 33 ± 5.4 | 24 ±4.4 | 21 ± 5.4 |

| Scores of RDQ (SD) | - | 16 ± 5.2 | 18 ± 0.8 | 15 ±0.7 | 16 ± 0.5 |

| No. of patients with bile regurgitation | 6 (15) | 22 (18.3) | 10 (25) | 12 (30) | 0 (0) |

| No. of patients with hiatus hernia | 18 (45) | 72 (60) | 18 (45) | 26 (65) | 28 (70) |

The majority of GERD patients presented abnormalities under NBI magnifying endoscopy. Increment of IPCLs appeared in a significantly higher proportion of GERD patients than in healthy controls (P < 0.05). Microerosion above and non-round pit pattern below the SCJ were also seen more frequently in patients with GERD (P < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the presence of prolonged, dilated, or tortuous IPCLs between patients and controls. The comparison among groups of different GERD subtypes revealed no evident difference in the number of patients presenting with abnormalities. No statistical differences were found in the increased, prolonged, dilated or tortuous IPCLs in the distal esophagus, as well as in the distributions of the mucosal pit patterns below the SCJ. As expected, RE patients were more likely to demonstrate microerosions. The NBI magnifying endoscopic features are shown in Table 2.

| NBI magnification findings | HC | GERD | |||

| GERD | NERD | RE | BE | ||

| Patients with abnormality | 28 (70) | 118 (98.3)a | 40 (100) | 38 (95) | 40 (100) |

| IPCLs increased | 8 (20) | 94 (78.3)a | 32 (80) | 32 (80) | 30 (75) |

| IPCLs prolonged | 14 (35) | 62 (51.7) | 24 (60) | 18 (45) | 20 (50) |

| IPCLs dilated | 8 (20) | 34 (28.3) | 10 (25) | 12 (30) | 12 (30) |

| IPCLs tortuous | 0 (0) | 2 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| Microerosions | 0 (0) | 50 (41.7)a | 14 (35)b | 24 (60) | 12 (30)b |

| Round pit pattern below SCJ | 28 (70) | 14 (11.7) | 4 (10) | 8 (20) | 2 (5) |

| Non-round pit pattern below SCJ | 12 (30) | 106 (88.3)a | 36 (90) | 32 (80) | 38(95) |

Qualitative analysis of the IPCLs increment was also performed. The numbers of IPCLs/field in the standardized four-quadrant images from the distal esophagus were counted manually in each subject. The results showed that the maximum, minimum and average numbers of IPCLs/field were significantly higher in GERD patients than in healthy controls (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference among the three subtype groups. More importantly, there was no linear increasing trend from NERD to RE to BE. The quantitative data are presented in Table 3.

| IPCLs/field | HC | GERD | |||

| GERD | NERD | RE | BE | ||

| Maximum (SD) | 144 ± 4.7 | 228 ± 4.8 | 229 ± 7.8 | 233 ± 8.2 | 220 ± 9.3 |

| Minimum (SD) | 103 ± 4.4 | 171 ± 3.8 | 162 ± 5.6 | 178 ± 6.7 | 174 ± 7.1 |

| Average (SD) | 119 ± 3.9 | 199 ± 3.9 | 193 ± 5.7 | 208 ± 6.8 | 195 ± 7.7 |

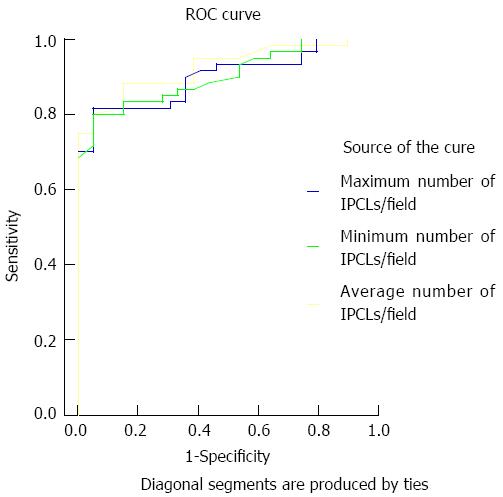

Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted for the maximum, minimum and average numbers of IPCLs/field in GERD patients to obtain the cut-off values with the best sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis, namely, diagnostic threshold. The best sensitivity and specificity for GERD were 81.7% and 95.0% at a maximum IPCLs/field count of 185, 80% and 95% at a minimum IPCLs/field count of 135, and 80% and 95% at an average IPCLs/field count of 162 (Figure 2). The areas under the curves were 0.900, 0.902 and 0.925, respectively.

GERD is considered to result from a long period of GER that causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications[1]. It has traditionally been approached as a spectrum of diseases with the same pathophysiological mechanisms. Based on conventional endoscopy and histopathological examination, GERD is generally categorized into three progressive stages: NERD, RE and BE. This understanding of GERD has a profound impact on its treatment, which focuses on esophageal mucosal injury[19]. Nevertheless, some researchers believe that GERD is a “tripartite” disease, rather than the model above. They take the three forms of GERD as being independent of each other, which may have their own mechanisms and should be approached with specific therapeutic modalities.

NBI, based upon the optical phenomenon that the depth of light penetrating into tissues depends on its wavelength, can capture the more detailed microstructure of the superficial mucosa. Some researchers have already used NBI magnifying endoscopy to observe the superficial mucosal changes in NERD patients, which cannot be observed under conventional endoscopy. For patients with RE and BE, micro changes have also been revealed with NBI magnifying endoscopy, in addition to the macro changes visualized by conventional endoscopy.

The microscopic IPCLs in the esophageal mucosa can be readily identified with the help of NBI magnifying endoscopy. A pilot feasibility trial conducted by Sharma et al[11] illustrated the clinical utility of NBI magnifying endoscopy, which presents a significant improvement over standard endoscopy in the diagnosis of GERD. Their results indicated that increased number and dilatation of IPCLs may be the best predictors for the diagnosis of GERD. Normal IPCLs appear to be hairpin-shaped and small in diameter, while there are evident changes in the morphology and arrangement of IPCLs in GERD patients[10,12-15]. However, the micro vascular differences among NERD, RE and BE patients have not been investigated before.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects in our study are consistent with former epidemiological data in China. The increased number of IPCLs identified in the GERD patients would be helpful for the diagnosis of the disease. There were no remarkable differences in the micro structural changes among patients with the three subtypes of GERD. Additionally, there is no trend of development from NERD to RE and then BE. As pointed out by some researchers, the micro changes of esophageal mucosa, such as increment of IPCLs and microerosion, could truly represent the regurgitation-induced damage, and the assessment of differences in micro mucosal structure and vascular architecture could provide useful information for predicting histopathological findings[11,20-22]. Therefore, our statistics imply that GERD may be a “tripartite” disease resulting from GER, rather than a spectrum of diseases.

NERD, RE and BE, as three independent forms of GERD, may have their respective pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and complications. As Fass et al[19] and Fass[23] have proposed, genetic factors may play a role in determining the phenotypes of GERD. Correspondingly, the diseases may require different therapeutic approaches and will have different prognoses and natural histories. There has already been clinical evidence for the independence of the three GERD forms. RE can be diagnosed with endoscopy and BE with endoscopy together with biopsy. However, conventional endoscopy is merely an exclusive examination for NERD. As to the 24 h pH monitoring, the symptomatic severity and frequency between NERD and RE are not significantly different, and they affect the patients’ quality of life similarly. Martinez et al[24] noted that the esophageal acid exposure of patients with NERD, RE and BE were different, and the reflux characteristics and symptom patterns suggested heterogeneity among their patients. In addition, the therapeutic efficacy in patients with different forms of GERD is different. A systematic review showed that a higher proportion of RE patients, compared with patients with NERD, achieved sufficient heartburn relief after the use of PPIs, and the therapeutic efficacy of NERD was poorer than that of RE[25]. The reason for the difference between NERD and RE patients in response to PPIs is still unclear. Limited data has indicated that NERD rarely moves on to RE with the prolonged course, relapse in cured RE patients after drug withdrawal often displays esophageal mucosal erosion, and BE is usually discovered during the first endoscopy examination instead of being developed from NERD or RE[19,26]. However, there have not been adequate follow-up studies to show the natural history of GERD.

It remains controversial whether GERD is a spectrum of diseases or not, and the relationships among the three forms of GERD has not yet been clarified. The montreal definition[1], which takes RE as an esophageal complication of GERD, has shifted the attention from esophageal mucosal lesion to reflux symptoms, and may influence the cognition of the subtypes of GERD. More epidemiological investigation, prospective follow-up research and clinical observation are needed to clarify this issue.

Despite the value of our study, some limitations exist. This is a single-center investigation with a limited number of patients. A multicenter study with a larger sample size will be more reliable. In addition, NBI magnifying endoscopy has not yet been widely used. The inspection area under the magnifying mode is very small, which makes it time-consuming to examine the entire distal esophagus.

If the view that NERD, RE and BE are relatively independent forms of GERD is confirmed, the therapeutic strategy for each form could be adjusted according to the specific mechanism of that form, increasing efficacy. Therefore, determination of the internal relationships among NERD, RE and BE has profound significance in clinical practice.

Gastroesophageal reflux diseases (GERD), with the subtypes of nonerosive reflux disease (NERD), reflux esophagitis (RE) and Barrett’s esophagus (BE), has been studied for many years. Conventional endoscopy and 24-h esophageal pH monitoring are common diagnostic approaches for GERD. However, it has not been clarified whether GERD is a spectrum of diseases or a “tripartite” disease.

Narrow band imaging (NBI) can capture the more detailed microstructure of the superficial mucosa. Some recent studies have shown that NBI magnifying endoscopy can reveal subtle changes of esophageal superficial mucosa in GERD patients. However, the microvascular differences among NERD, RE and BE patients have not been investigated before using this new technology.

It has been reported that patients with GERD could potentially progress from mild NERD toward RE, then BE, and finally neoplasia, which indicates that GERD may be a spectrum of diseases. However, some researchers disagree. They regard GERD a “tripartite” disease. The relationships among the three forms of GERD have not been fully investigated. The present study aimed to explore the relationships among the three subtypes of GERD by observing the subtle vascular changes detected by NBI magnifying endoscopy. The authors study might provide a basis for further diagnosis and treatment of GERD.

By dividing GERD into three unique subtypes, physicians or surgeons may concentrate on the specific mechanisms leading to the development of a subtype of GERD and improve the specific therapeutic modalities that benefit the patients with subtype of disease.

Normal intrapapillary capillary loops (IPCLs) exist in the esophageal submucosa, and are dot-like structures, arranged at regular intervals of about 100 μm. The microscopic IPCLs in the esophageal mucosa can be readily identified with the help of NBI magnifying endoscopy. Under magnifying endoscopy, they appear hairpin-shaped and small in diameter. Their morphology is dynamic and could be affected by neoplasia and inflammation.

In this study, the authors conducted research on the relationships among the three common forms of GERD using NBI magnifying endoscopy to observe the micro changes in the patients. All efforts to establish classifications in this very frequent disease are welcome. NBI facilitates diagnosis and includes new imaging areas. The results demonstrated that the GERD patients had similar micro changes in the distal esophagus, and they indicated that the disease might be a model of “tripartite” disease, rather than a spectrum of diseases.

P- Reviewers: Bordas JM, Pei ZH S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2448] [Article Influence: 128.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Stanghellini V. Relationship between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and lifestyle, psychosocial factors and comorbidity in the general population: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:29-37. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1261] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Moayyedi P, Axon AT. Review article: gastro-oesophageal reflux disease--the extent of the problem. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22 Suppl 1:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fock KM, Talley N, Hunt R, Fass R, Nandurkar S, Lam SK, Goh KL, Sollano J. Report of the Asia-Pacific consensus on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:357-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Watanabe Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, Matsumoto T, Nishikawa H, Arakawa T. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:26-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cho YS, Choi MG, Jeong JJ, Chung WC, Lee IS, Kim SW, Han SW, Choi KY, Chung IS. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Asan-si, Korea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:747-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lim SL, Goh WT, Lee JM, Ng TP, Ho KY. Changing prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux with changing time: longitudinal study in an Asian population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:995-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pace F, Bianchi Porro G. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: a typical spectrum disease (a new conceptual framework is not needed). Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:946-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoshida T, Inoue H, Usui S, Satodate H, Fukami N, Kudo SE. Narrow-band imaging system with magnifying endoscopy for superficial esophageal lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:288-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharma P, Wani S, Bansal A, Hall S, Puli S, Mathur S, Rastogi A. A feasibility trial of narrow band imaging endoscopy in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:454-464; quiz 674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fock KM, Teo EK, Ang TL, Tan JY, Law NM. The utility of narrow band imaging in improving the endoscopic diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:54-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tseng PH, Chen CC, Chiu HM, Liao WC, Wu MS, Lin JT, Lee YC, Wang HP. Performance of narrow band imaging and magnification endoscopy in the prediction of therapeutic response in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kosaka R, Tanaka K, Toyoda H, Hamada Y, Aoki M, Noda T, Imoto I, Takei Y, Nagahama M. Dilated intrapapillary capillary loops by magnifying endoscopy: Usefulness for diagnosis of GERD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Banerjee R, Pratap N, Ramchandani M, Tandan M, Rao GV, Reddy DN. Narrow Band Imaging (NBI) Can Detect Minimal Changes in Non Erosive Reflux Disease (NERD) Which Resolve with PPI Therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:AB356. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in RCA: 1652] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Endo T, Awakawa T, Takahashi H, Arimura Y, Itoh F, Yamashita K, Sasaki S, Yamamoto H, Tang X, Imai K. Classification of Barrett’s epithelium by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 786] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Fass R, Ofman JJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease--should we adopt a new conceptual framework? Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1901-1909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stolte M, Vieth M, Schmitz JM, Alexandridis T, Seifert E. Effects of long-term treatment with proton pump inhibitors in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on the histological findings in the lower oesophagus. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1125-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Calabrese C, Fabbri A, Bortolotti M, Cenacchi G, Areni A, Scialpi C, Miglioli M, Di Febo G. Dilated intercellular spaces as a marker of oesophageal damage: comparative results in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease with or without bile reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:525-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kiesslich R, Kanzler S, Vieth M, Moehler M, Neidig J, Thanka Nadar BJ, Schilling D, Burg J, Nafe B, Neurath MF. Minimal change esophagitis: prospective comparison of endoscopic and histological markers between patients with non-erosive reflux disease and normal controls using magnifying endoscopy. Dig Dis. 2004;22:221-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fass R. Gastroesophageal reflux disease revisited. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:S1-S10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Martinez SD, Malagon IB, Garewal HS, Cui H, Fass R. Non-erosive reflux disease (NERD)--acid reflux and symptom patterns. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:537-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dean BB, Gano AD, Knight K, Ofman JJ, Fass R. Effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in nonerosive reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:656-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kuster E, Ros E, Toledo-Pimentel V, Pujol A, Bordas JM, Grande L, Pera C. Predictive factors of the long term outcome in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: six year follow up of 107 patients. Gut. 1994;35:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |