Published online Dec 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8321

Revised: August 12, 2013

Accepted: September 15, 2013

Published online: December 7, 2013

Processing time: 225 Days and 5.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the use of the Roux loop on the postoperative course in patients submitted for gastroenteroanastomosis (GE).

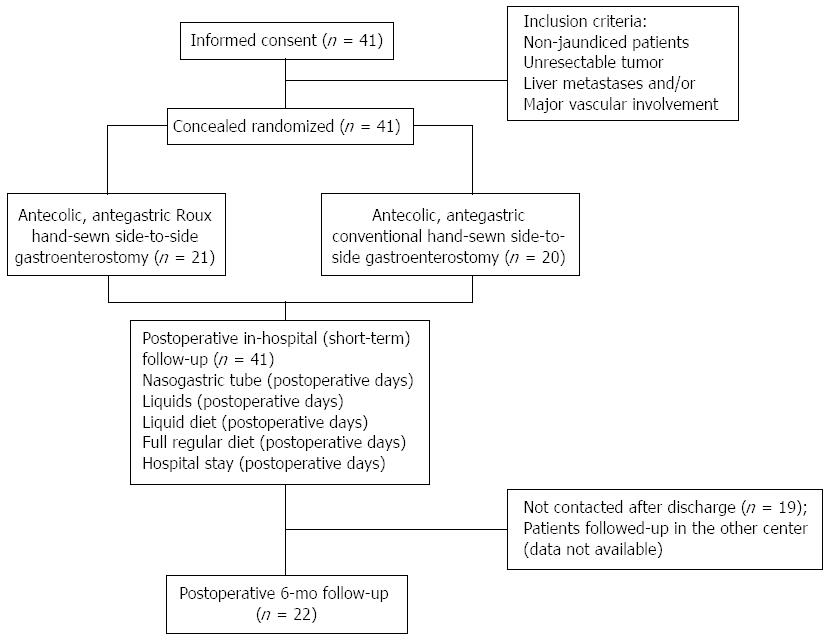

METHODS: Non-jaundiced patients (n = 41) operated on in the Department of General and Transplant Surgery in Lodz, between January 2010 and December 2011 were enrolled. The tumor was considered unresectable when liver metastases or major vascular involvement were confirmed. Patients were randomized to receive Roux (n = 21) or conventional GE (n = 20) on a prophylactic basis.

RESULTS: The mean time to nasogastric tube withdrawal in Roux GE group was shorter (1.4 ± 0.75 vs 2.8 ± 1.1, P < 0.001). Time to starting oral liquids, soft diet and regular diet were decreased (2.3 ± 0.86 vs 3.45 ± 1.19; P < 0.001; 3.3 ± 0.73 vs 4.4 ± 1.23, P < 0.001 and 4.5 ± 0.76 vs 5.6 ± 1.42, P = 0.002; respectively). The Roux GE group had a lower use of prokinetics (10 mg thrice daily for 2.2 ± 1.8 d vs 3.7 ± 2.6 d, P = 0.044; total 62 ± 49 mg vs 111 ± 79 mg, P = 0.025). The mean hospitalization time following Roux GE was shorter (7.7 d vs 9.6 d, P = 0.006). Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) was confirmed in 20% after conventional GE but in none of the patients following Roux GE.

CONCLUSION: Roux gastrojejunostomy during open abdomen exploration in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer is easy to perform, decreases the incidence of DGE and lowers hospitalization time.

Core tip: The lower rate of delayed gastric emptying, which determines lower use of prokinetics after Roux compared to conventional antegastric gastroenterostomy (GE) suggested that prophylactic Roux GE should be performed during surgical exploration of patients with unresectable pancreatic head tumors. The length of hospital stay is shorter following palliative Roux GE, thus the treatment costs of these patients are likely to be smaller. Further research is needed on the cost-effectiveness of prophylactic Roux GE in unresectable pancreatic cancer.

- Citation: Szymanski D, Durczynski A, Nowicki M, Strzelczyk J. Gastrojejunostomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic head cancer - the use of Roux loop significantly shortens the hospital length of stay. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(45): 8321-8325

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i45/8321.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8321

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is a serious public health problem. It accounts only for 2% of new cancer diagnoses in both men and women, but it ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States[1]. Despite recent developments in new imaging techniques and improved staging studies, the incidence rate of early pancreatic cancer has changed little over the last decades. Nonetheless, the surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer is palliative in more than 80%, with median overall survival of 6 mo when diagnosed at the metastatic stage[2].

Nowadays, with increasing incidence of pancreatic cancer, annual costs for therapy have risen rapidly[3-6]. The average monthly cost of treatment of a patient with pancreatic cancer is almost $7000; in patients with terminal disease this can rise to as much as $65557[7]. New anti-cancer agents are the largest expenditure, although the greater part of the costs comes from palliative surgical procedures and postoperative hospitalization care[8]. Pancreatic surgeries in high-volume centers are associated with low mortality, but high morbidity[9-12]. Postoperative complications increase the duration of the hospital stay and treatment costs.

Limited survival benefit and unfavorable cost-effectiveness make surgery for later stages of pancreatic cancer controversial. From this perspective, the optimal method of palliation is uncertain when tumor unresectability is determined at exploration. Shortening of the length of postoperative hospital stay and associated direct costs is an important part of the development of the new palliative procedures.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the influence of two different surgical techniques for creating gastroenterostomy on the postoperative delayed gastric emptying (DGE) rate and the length of hospital stay in non-jaundiced patients with unresectable pancreatic head cancer.

This prospective, randomized study comprised non-jaundiced patients with unresectable pancreatic head tumor (n = 41), hospitalized in the Department of General and Transplant Surgery of Medical University in Lodz, who received solitary gastroenterostomy on a prophylactic basis from January 2010 to December 2011. Patients were randomized to receive either antecolic Roux (n = 21), or conventional antegastric hand-sewn side-to-side gastroenterostomy (n = 20). Before surgery, each patient was allotted a code (Roux or conventional group). Blinded investigators performed all postoperative assessments.

All patients gave signed, written, informed consent for the study. Most of the patients (n = 37) originally presented with jaundice in the endoscopic units, where the biliary stents have been inserted. As endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients is challenging, anastomoses was performed without the stomach being transected or divided. Therefore, blockage of the biliary stents causing recurrent jaundice could easily have been managed with stent replacement, without the need of percutaneous drainage. The risk of occlusion of stents increased in our group after 3 mo, thus elective stent exchange at 3-6 mo was performed using the standard technique. Changing a stent was available for the Roux and conventional GE group.

The tumor was considered unresectable when the presence of distant metastases or major vascular involvement was confirmed. Conventional GE was performed in a standard side-to-side antecolic fashion, 20 cm from the ligament of Treitz. Roux GE was constructed as follows. A Roux-en-Y intestinal loop, 60 cm long, was prepared by transecting the jejunum 20 cm from the ligament of Treitz, which was then anastomosed to the stomach in an antecolic fashion to construct a latero-lateral gastro-jejunostomy. The intestinal continuity was restored by a jejuno-jejunal, hand-sewn anastomosis. In all cases, the Tru-cut biopsy of the tumor was obtained. All patients without microscopic diagnosis of the cancer were excluded from the study. Eventually, 21 patients with pancreatic cancer confirmed by pathological report received Roux gastroenterostomy and 20 received the conventional GE. Experienced pancreatic surgeons performed all surgeries. All patients provided written informed consent for the study.

The postoperative course of every patient was documented retrospectively, with special regard to the length of hospital stay as a primary endpoint, as well as prokinetic therapy duration, the number of days of nasogastric tube decompression (NGT), the start of oral fluids, soft diet and solid diet (secondary endpoints). According to recent studies[13], DGE was defined as (1) the nasogastric decompression lasting more than 3 postoperative days (POD) or the need for reinsertion of NGT for persistent nausea and vomiting after POD 3; (2) the inability to tolerate a solid diet by POD 7; or (3) the need for prokinetic agents after POD 10. All data were shown in the text and tables as means ± SD.

All statistical calculations were performed using SigmaPlot version 12.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, United States) with the level of statistical significance set at P < 0.05. To compare the differences in mean length of hospital stay, time to the postoperative nasogastric tube withdrawal, liquids, liquid diet and full regular diet following Roux and conventional GE, we applied the parametric t test and non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. In the t-test, equal variance tests were performed to demonstrate differences in the use of prokinetics. All data were shown in the text and tables as means or medians ± SD.

Figure 1 is a flow chart of patient enrollment, randomization and progress through the study. The demographics of the patients from both groups are summarized in Table 1. The mean operative time of Roux GE was 55 ± 25 min vs 48 ± 36 min for conventional GE. Shorter mean time to the postoperative nasogastric tube withdrawal (by 50%, P < 0.001), liquids (by 33.3%, P < 0.001), liquid diet (by 25%, P < 0.001) and full regular diet (by 19.6%, P = 0.002) following Roux in contrast to conventional GE was demonstrated (Table 2). No patients required reinsertion of the nasogastric tube. Delayed gastric emptying did not occur after Roux GE, whereas it was confirmed in four cases after conventional GE (20%). The Roux GE group had a lower use of prokinetics compared with conventional GE (10 mg of metoclopramide iv thrice daily for 2.2 ± 1.8 d vs 3.7 ± 2.6 d, P = 0.044; total 62 ± 49 mg vs 111 ± 79 mg, P = 0.025; respectively). The mean length of hospital stay was shorter following palliative Roux GE (7.7 d vs 9.6 d; P = 0.006). The recurrence of jaundice and cholangitis (23% of patients) and mean survival were comparable in both groups during 6-mo follow-up.

| Patients characteristics and demographics | Roux GE | Conventional GE |

| Age (yr) | 60.2 ± 10.6 | 61.6 ± 8.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 10 (50) | 8 (40) |

| Male | 10 (50) | 12 (60) |

| Reason for unresectibility | ||

| Local | 15 (75) | 14 (70) |

| Liver metastases | 5 (25) | 6 (30) |

| Indication | Prophylactic | Prophylactic |

| Reconstruction | Antecolic | Antecolic |

| Position | Antegastric | Antegastric |

| Postoperative course | Roux GE | Conventional GE | Differences in the Roux and conventional GE (P value) | Power analysis1 | ||

| mean ± SD | Median | mean ± SD | Median | |||

| Nasogastric tube (postoperative days) | 1.4 ± 0.75 | 1 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 3 | < 0.001 | 0.962 |

| Liquids (postoperative days) | 2.3 ± 0.86 | 2 | 3.45 ± 1.19 | 3 | < 0.001 | 0.86 |

| Liquid diet (postoperative days) | 3.3 ± 0.73 | 3 | 4.4 ± 1.23 | 4 | < 0.001 | 0.853 |

| Full regular diet (postoperative days) | 4.5 ± 0.76 | 4 | 5.6 ± 1.42 | 5 | 0.002 | 0.784 |

| Hospital stay (postoperative days) | 7.7 ± 3.01 | 7 | 9.6 ± 2.79 | 10 | 0.006 | 0.499 |

The palliative treatment of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer is a significant economic burden to public healthcare. As limited survival is expected and the total costs of treatment per incident case are high, there are general concerns about the necessity of palliative procedures, which most frequently surgical in patients with pancreatic cancer. Biliary stents or biliary bypass in patients with jaundice have a definite role because they decrease morbidity; however, performing prophylactic gastroenterostomy is still a matter of debate for several reasons. First, it is difficult to predict the number of patients who will develop duodenal obstruction. Second, delayed gastric emptying is a frequent complication after gastroenterostomy. It is usually not a life-threatening condition and can be treated conservatively, although it compromises quality of life, prolongs the hospital stay and adds to hospital costs in patients with a very limited life expectancy. Recent reports have proved that prophylactic gastroenterostomy should be constructed in patients that are found to have unresectable pancreatic cancer at exploration[14]; therefore, it is necessary to decrease the incidence of DGE.

The occurrence of DGE after gastroenterostomy varies from 9% to 26%[15]. These differences may reflect considerable variations in DGE definition in previous studies. However, we used the strict definition of DGE suggested by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer[13].

DGE is a multifactorial problem, which has been linked to tumor involvement of the coeliac axis and interruption of splanchnic innervations, as well as the technique of gastroenterostomy[15-20]. Our study confirmed that construction of a gastrojejunal anastomosis with an isolated Roux loop was beneficial (Table 2). The incidence of postoperative DGE was reduced. The procedure was technically simple and convalescence was rapid. Success may depend on already known parameters. Roux anastomosis remains mechanically efficient; however, postoperative gastric motility is temporarily impaired.

The development of laparoscopic surgical methods offers further reduction in costs associated treatment of unresectable pancreatic cancer. Laparoscopic gastric bypass is an effective and safe procedure for patients with gastric outlet obstruction. The hospital stay is shorter than after open surgery and recovery is more rapid[21]. It is technically feasible[22] for Roux gastrojejunostomy to be utilized for laparoscopic approach[23-26]. Thus, it may reveal new perspectives in prophylactic gastrojejunostomy in patients with unresetable pancreatic cancer. If curative resection is not possible, the response to chemotherapy is expected. Minimally invasive laparoscopic Roux GE may enable the patient to receive postoperative chemotherapy earlier. However, until now, the laparoscopic approach in pancreatic cancer has remained limited.

In conclusion, Roux gastroenterostomy should be performed routinely during open abdomen exploration in patients with unresectable pancreatic head carcinoma, because it is easy to perform, is free of specific complications, decreases incidence of DGE, and reduces the length of hospital stay and associated health care costs.

The surgical palliation is an important component of the treatment of pancreatic head cancer. However, the optimal method of palliation is uncertain when tumor unresectability is determined at exploration.

Prophylactic gastroenterostomy should be constructed in patients who are found to have unresectable pancreatic cancer at exploration. Nevertheless, delayed gastric emptying is a frequent complication after gastroenterostomy. This research evaluated the use of different surgical techniques for creating gastroenterostomy on the postoperative delayed gastric emptying (DGE) rate and the hospital length of stay in non-jaundiced patients with unresectable pancreatic head cancer.

This is the first paper to precisely describe differences in the postoperative course between antecolic Roux and conventional antegastric hand-sewn side-to-side gastroenterostomy in patients with unresectable pancreatic head cancer.

The study results suggest that Roux instead of conventional antegastric gastroenterostomy should be performed routinely during open abdomen exploration in patients with unresectable pancreatic head carcinoma, because it is easy to perform, is free of specific complications, decreases incidence of DGE, and reduces the length of hospital stay and associated health care costs.

The results evaluate the influence of two different surgical techniques of creating gastroenterostomy on the postoperative delayed gastric emptying rate and the length of stay hospital in non-jaundiced patients with unresectable pancreatic head cancer. This is an interesting randomized study, though it suffers from many vulnerabilities.

P- Reviewer: Sgourakis G S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Stewart GJ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Jemal A, Murray T, Samuels A, Ghafoor A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:5-26. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Quiros RM, Brown KM, Hoffman JP. Neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | O’Neill CB, Atoria CL, O’Reilly EM, LaFemina J, Henman MC, Elkin EB. Costs and trends in pancreatic cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118:5132-5139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bardou M, Le Ray I. Treatment of pancreatic cancer: A narrative review of cost-effectiveness studies. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:881-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tam VC, Ko YJ, Mittmann N, Cheung MC, Kumar K, Hassan S, Chan KK. Cost-effectiveness of systemic therapies for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:e90-e106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ishii H, Furuse J, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Nakagohri T, Takahashi S, Gotohda N, Nakachi K, Suzuki E, Yoshino M. Treatment cost of pancreatic cancer in Japan: analysis of the difference after the introduction of gemcitabine. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:526-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ogdie AR, Lee BC, Li J, Maglaris D, Siddiqi A, Marshall J. The cost of treating pancreatic cancer: A pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16004. |

| 8. | Janes RH, Niederhuber JE, Chmiel JS, Winchester DP, Ocwieja KC, Karnell JH, Clive RE, Menck HR. National patterns of care for pancreatic cancer. Results of a survey by the Commission on Cancer. Ann Surg. 1996;223:261-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ho CK, Kleeff J, Friess H, Büchler MW. Complications of pancreatic surgery. HPB (Oxford). 2005;7:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hwang SI, Kim HO, Son BH, Yoo CH, Kim H, Shin JH. Surgical palliation of unresectable pancreatic head cancer in elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:978-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lesurtel M, Dehni N, Tiret E, Parc R, Paye F. Palliative surgery for unresectable pancreatic and periampullary cancer: a reappraisal. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:286-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Singh SM, Longmire WP, Reber HA. Surgical palliation for pancreatic cancer. The UCLA experience. Ann Surg. 1990;212:132-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2324] [Article Influence: 129.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hüser N, Michalski CW, Schuster T, Friess H, Kleeff J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prophylactic gastroenterostomy for unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:711-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Horstmann O, Kley CW, Post S, Becker H. ‘Cross-section gastroenterostomy’ in patients with irresectable periampullary carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2001;3:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shyr YM, Su CH, Wu CW, Lui WY. Prospective study of gastric outlet obstruction in unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2000;24:60-4; discussion 64-5. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1999;230:322-38; discussion 322-38;. [PubMed] |

| 18. | van der Schelling GP, van den Bosch RP, Klinkenbij JH, Mulder PG, Jeekel J. Is there a place for gastroenterostomy in patients with advanced cancer of the head of the pancreas? World J Surg. 1993;17:128-32; discussion 132-3. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Jacobs PP, van der Sluis RF, Wobbes T. Role of gastroenterostomy in the palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1989;42:145-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sarr MG, Cameron JL. Surgical management of unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas. Surgery. 1982;91:123-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Park JM, Chi KC. Unresectable gastric cancer with gastric outlet obstruction and distant metastasis responding to intraperitoneal and folfox chemotherapy after palliative laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy: report of a case. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:109. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Zevin B, Aggarwal R, Grantcharov TP. Simulation-based training and learning curves in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Br J Surg. 2012;99:887-895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kendrick ML. Laparoscopic and robotic resection for pancreatic cancer. Cancer J. 2012;18:571-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim SC, Song KB, Jung YS, Kim YH, Park do H, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Park KM. Short-term clinical outcomes for 100 consecutive cases of laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy: improvement with surgical experience. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:95-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Palanivelu C, Jani K, Senthilnathan P, Parthasarathi R, Rajapandian S, Madhankumar MV. Laparoscopic pancreaticoduodenectomy: technique and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:222-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Muniraj T, Barve P. Laparoscopic staging and surgical treatment of pancreatic cancer. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |